In Kurt Vonnegut’s groundbreaking 1963 satirical novel, Cat’s Cradle, the author lays out the framework of the jargon-heavy Bokononist religion. One recurring concept is the karass—a group of people pulled together by forces outside of their control to complete a mission beyond their understanding. If you’re a member of a karass, you don’t really know who’s in it with you or what you’re doing, but you might pick up the clues through context. Anyone who’s formed a band and experienced the unexplainable, inevitable pull of musical connection among a group of musicians who often come together despite sometimes improbable circumstances can surely relate.

Without citing Vonnegut, actor and musician Michael Imperioli, whose A-list filmography includes early career parts in Goodfellas and Trees Lounge through his recent role as Dominic Di Grasso on season two of The White Lotus, has felt these forces at work throughout his life. Whether it’s foresight, intuition, or even magic, Imperioli jokes that some friends have accused him of being a witch. Whether or not that’s the case is probably a matter of perspective.

Take, for example, Imperioli’s relationship with John Ventimiglia. In 1986, the two aspiring actors, who’d already known each other for years, were roommates when Ventimiglia, also a musician playing in bands around the New York and New Jersey underground rock scenes at the time, showed the then-20-year-old Imperioli his first chords on a guitar. He quickly took to the instrument, forming his first band almost immediately. At the end of the next decade, the two were cast to play life-changing roles on The Sopranos—Imperioli as Tony Soprano-protégé Christopher Moltisanti and Ventimiglia as the capo’s lifelong pal, chef Artie Bucco—forever intertwining their artistic paths on one of the most important television shows of all time.

SoundStream

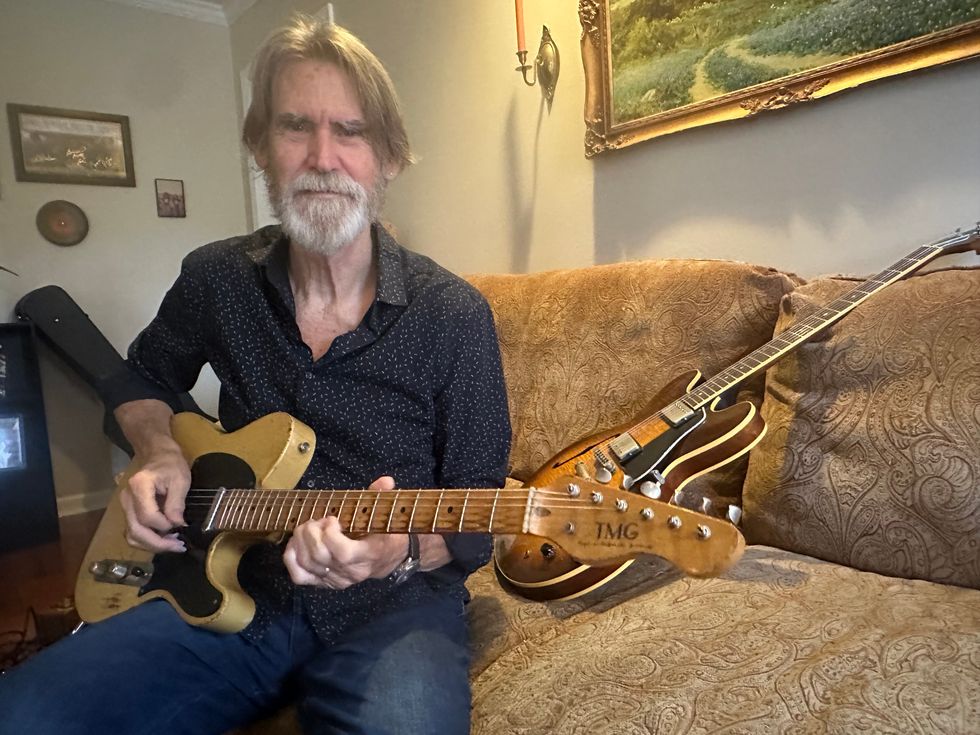

Coincidence has tied Imperioli to his guitars as well. After falling in love with his 1966 Fender Jaguar, which he had Rick Kelly of Carmine Street Guitars modify with humbuckers, he decided to track down a second. When that guitar landed on Kelly’s bench and the luthier popped the neck off, they learned just how much the two Jaguars had in common. “Those two guitars were made in the same factory on the same day in September of 1966. This is the year I was born,” Imperioli points out, incredulously. “And they’re maybe 30 serial numbers apart.”

So it goes that “very strange connections” pulled Imperioli into orbit with drummer Olmo Tighe and bassist Elijah Amitin in the mid 2000s and led them to form their now-long-standing trio, ZOPA. Imperioli and Tighe had first met while working on the 1994 film Postcards from America, when Olmo was only eight years old. They didn’t reconnect until years later, when Imperioli ran into Olmo’s older brother, Michael, at a party. In this chance meeting, Imperioli learned Olmo was drumming, and “for some bizarre reason—and I still don’t know why—I thought he and I should play music together,” he recalls.

“I had the idea of forming a trio, and it was really inspired by Galaxie 500 and what they did with a trio and the way it was three distinctive musicians coming from three different point of views making this one thing happen together.”

The two eventually connected against the odds, Imperioli going to great lengths to find the drummer, and they set up a time to rehearse. On bass, Olmo suggested Amitin, who, they learned, had his own family connections to Imperioli through his old management and family—real small world kind of stuff. By the time the three ended up in the same room, they already felt like they belonged together, and ZOPA was born.

Michael Imperioli's Gear

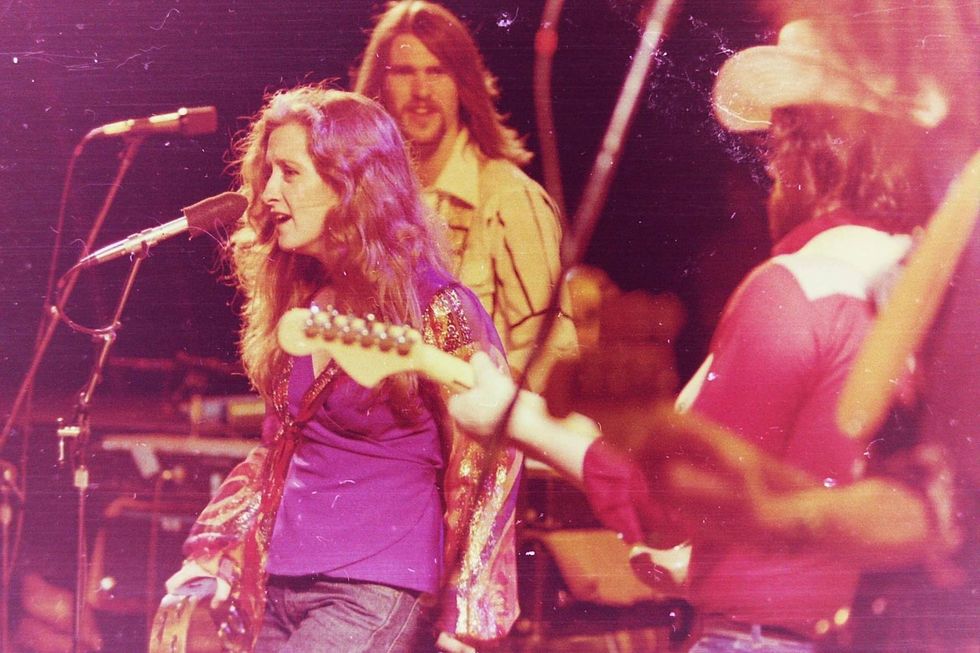

On stage, ZOPA manifest the trio energy of their influences, from Lou Reed to Dinosaur Jr. to Galaxie 500.

Guitars

- Two 1966 Fender Jaguars

Amps

- Fender Twin Reverb

- Fender Princeton Reverb

Effects

- Death By Audio Fuzz War

- Dunlop Cry Baby

- EHX Small Clone

- EHX Big Muff

- MXR Distortion +

- MXR Duke of Tone

- MXR Phase 100

- MXR Carbon Copy

- Neunaber Immerse Reverberator

- Walrus Audio Phoenix power supply

Strings and Picks

- D’Addario XL or Ernie Ball .010s

- Custom ZOPA Dunlop Tortex .88 mm

As much as this is a fun story, to Imperioli, it’s much more. The relationship, and their coming together seemingly at random to discover connections between them, resonates. And it makes ZOPA an extra tightly knit unit. (The band became even tighter when Tighe married Imperioli’s cousin and the two became family.) “I think it comes from good intentions and getting a good perception of somebody and wanting to further that connection,” he says.

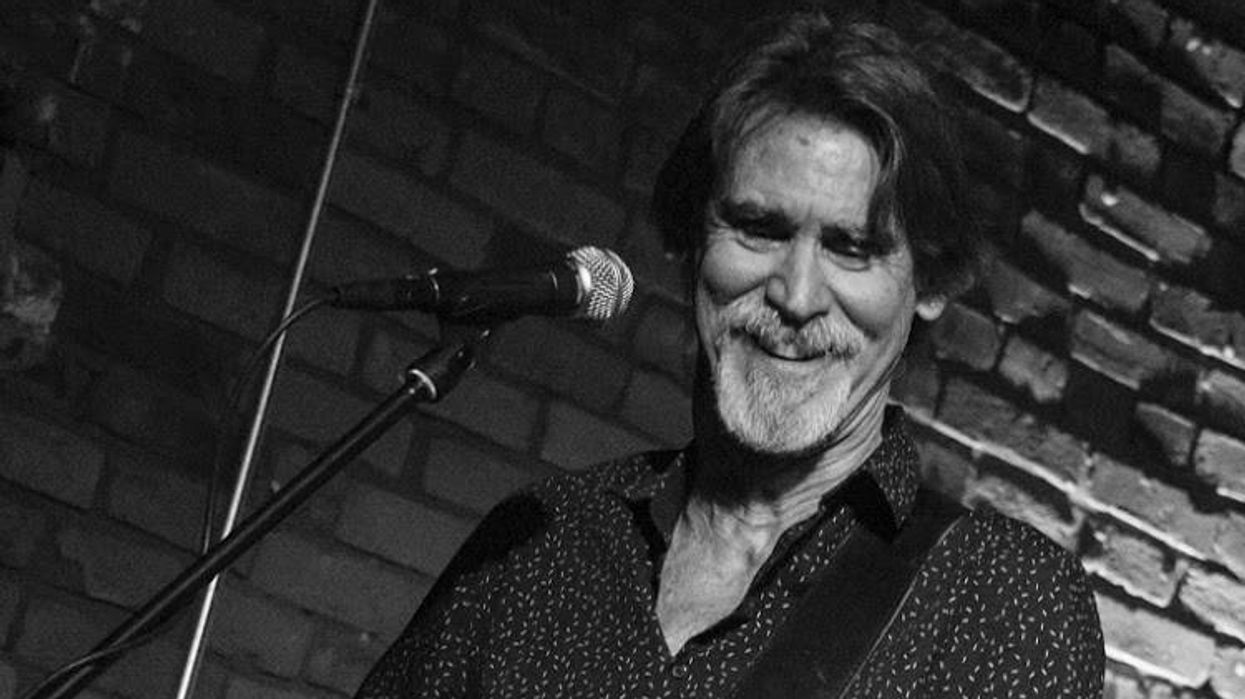

At a recent show at Philadelphia rock club Kung Fu Necktie, there was a different kind of energy buzzing throughout ZOPA’s tightly packed audience. It was a frenetic, excited, and celebratory scene, with fans at times reaching for strums on Imperioli’s Jaguar as the band kicked out a set of mostly new songs from their newest, Diamond Vehicle, which was yet to be released at the time, as well as a song or two from their debut, La Dolce Vita.“That love of music was definitely infused into The Sopranos.”

ZOPA is a formidable unit; they’re a trio, with all the special rock ’n’ roll spirit that implies. Tighe appears on stage as bashful at first, but he emerges as a basher in the style of Dinosaur Jr. drummer Murph (though Imperioli suggests John Bonham is probably his more dominant reference point). At stage left, Amitin bops around confidently, donning a rock stance, bare chest popping through a one-third-unbuttoned shirt, easily dominating his Peavey 4-string. Imperioli’s presence lands somewhere between the two. He’s casual and engaging, comfortable taking the limelight during brief, melodic Big Muff-driven solo spots, but otherwise delivering a low-key stagecraft that evokes that of his biggest influences, which range from Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground to Dinosaur Jr. to dream-pop pioneers Galaxie 500.

Those influences play out across Diamond Vehicle. Produced by John Agnello, whose extensive credits include Dinosaur Jr., Kurt Vile, Lee Ranaldo, and Son Volt, the album evokes intimate rock clubs, where live music is mutually transformed by audience and artist. A few days after that show in Philly, we caught up with Imperioli to talk about his life in music.There was a lot of energy at your show the other night. Is that the ZOPA vibe or was that a Philly thing?

Imperioli: I have to say the Philadelphia audiences are consistently fantastic. I think it’s kind of a combination, but Philly has a certain spirit. I think just the spirit of the city, especially that neighborhood [Fishtown], where we’ve played a few times. They love music and they want to have a good time and they let you know it when they’re having fun. It makes it really exciting as a performer, without a doubt.

The audience included all ages of people but skewed young. Has that always been the case?

Imperioli: We started performing in 2006. In those first seven years, our audiences were more our own age group for the most part. We stopped playing together around 2013 for about seven years because I was living on the West Coast. During the pandemic, we released an album [La Dolce Vita]. I was on Instagram and often would post things about music, not just our music, but my musical tastes. When we started playing together again in 2021, we noticed that the audience had gotten a lot younger than when we started the band.

I think it’s a combination of being able to reach younger people through social media, and through some of the other projects I’ve been involved in, and The Sopranos finding a younger audience, and The White Lotus, which kind of hit a younger audience.You started playing when you were 20 years old. How soon after learning your first chords did you start performing?

Imperioli: I immediately started playing with one guy who was in my acting class who had been a musician first, and then two other musicians. We started a band that was really kind of a no-wave band based on the Mudd Club scene of the early ’80s, and it was just instrumental. There was no singer, and there was guitar, bass, and drums. I had the only guitar I could afford at the time, which was a nylon-string acoustic guitar. It was the cheapest thing in the store. I tried to mic it and it didn’t really sound good. Then, I bought a little pickup and glued it, and then I was able to plug into the amplifier and try to make sounds. And that’s how I started playing.

The band’s second record, Diamond Vehicle, was recorded with producer John Agnello, known for his work with artists such as Dinosaur Jr. and Kurt Vile.

What was that band called?

Imperioli: Black Angus. I didn’t really know anything. Then, I bought my first electric guitar, maybe a year or two after. That was a Telecaster, which I bought at Matt Umanov Guitars, which used to be on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. It was a little easier to play no-wave music with an electric guitar.

We only recorded demos, didn’t record in a studio at all. We did play one gig. It was an Earth Day benefit at a place called McGovern’s, which was a dive bar that had live music in SoHo on Spring Street.

Who influenced your no-wave guitar playing?

Imperioli: One of my favorite guitarists is Pat Place from the Bush Tetras. We did a benefit with them a couple of years ago, which was kind of a thrill to be on the bill with them. Pat Place’s approach to the guitar always really cut through for me. I think she’s somebody who really found her own style and really mastered that and just adds such a unique dynamic to the music.

“Going back to when I was 20, I was playing in bands and doing little plays and writing and producing plays and directing plays…. That’s always been my life.”

Speaking of that scene, I’ve seen you post on Instagram about Robert Quine.

Imperioli: Robert Quine, I think, was a genius. From Richard Hell’s Band, the Voidoids, and his work with Lou Reed. He was a distinctive, expressive guitar player with a unique voice that always stood out in his work. As a young person, he recorded the Velvet Underground at Max’s Kansas City, then eventually wound up playing with Lou.

I think Lou Reed is a very underrated guitar player. Of course, as a rhythm guitar player, it’s known, but his leads were very interesting, especially when he was improvising. He really was able to express a certain point of view from inside those songs. And when Quine decided to play with Lou, one of the stipulations he made was that he wanted Lou to play leads as well.

After Black Angus, you were in the band Wild Carnation.

Imperioli: Yeah, it was a couple of years later, before they were named Wild Carnation.

I was singing, I wasn’t playing guitar. That was kind of a brief thing for me. I had to leave the country for some project, and they really were ready to record. So, it wound up not being a good time for that.

Then, I met Olmo and Elijah in 2006, and I had been working on guitar stuff then. Shortly after we started playing, I started taking some lessons with Richard Lloyd from Television, who basically taught me how to practice, and that made a big difference. I mean, I was practicing before, but I just learned different ways to approach it from him. It was a really big, big step for me.

I only had a few lessons with him, but they really made a big impact over the course of a few months. He’s a very demanding and exacting teacher.

Michael Imperioli with his humbucker-loaded 1966 Fender Jaguar.

So, ZOPA was your first band that was based more around your songwriting.

Imperioli: I brought some songs that I had had kicking around for a while, and we created some songs—the process is pretty collaborative. Some songs come from a drumbeat, some songs come from a bass line, some come from ideas that Elijah or Olmo have lyrically. Some come from me, even if it’s something that I bring in like a chord progression and some lyrics. It really doesn’t become a ZOPA song until it’s worked out by all of us.

I had the idea of forming a trio, and it was really inspired by Galaxie 500 and what they did with a trio and the way it was three distinctive musicians coming from three different point of views making this one thing happen together. It’s never just a singer-songwriter with a rhythm section. That’s kind of always been the approach.

Dinosaur Jr. is an example that is similar, which is a big influence on me, and I think on ZOPA as well.

I can hear the Dinosaur influence in the band. Has J been a longtime favorite of yours?

Imperioli: For a long time. J’s a virtuoso as far as rock guitar goes, he’s really quite incredible.

My abilities are so far less than his, but sonically how he uses the guitar, and how he approaches a lead, the way he expresses himself, especially his lead playing, I think is spectacular and sometimes really breathtaking and moving.

I think my favorite guitar solo in all of rock might be the song “Pick Me Up,” from the Beyond album. Three minutes into the song, he starts this three-and-a-half-minute guitar solo. I think it’s just genius and perfection, and he’s definitely a compass point of guitar playing for me.

“I’m someone who likes to be engaged in things that are creative and exciting to me and find a way to keep doing that.”

When did you start writing songs?

Imperioli: Pretty much right when I started playing guitar. There’s one song that was on our first album that I think was the first song I ever wrote, called “Roll It Off Your Skin.” The last verse was written when I was living at the Chelsea Hotel in ’95, and then we started playing it together 10 years after that.

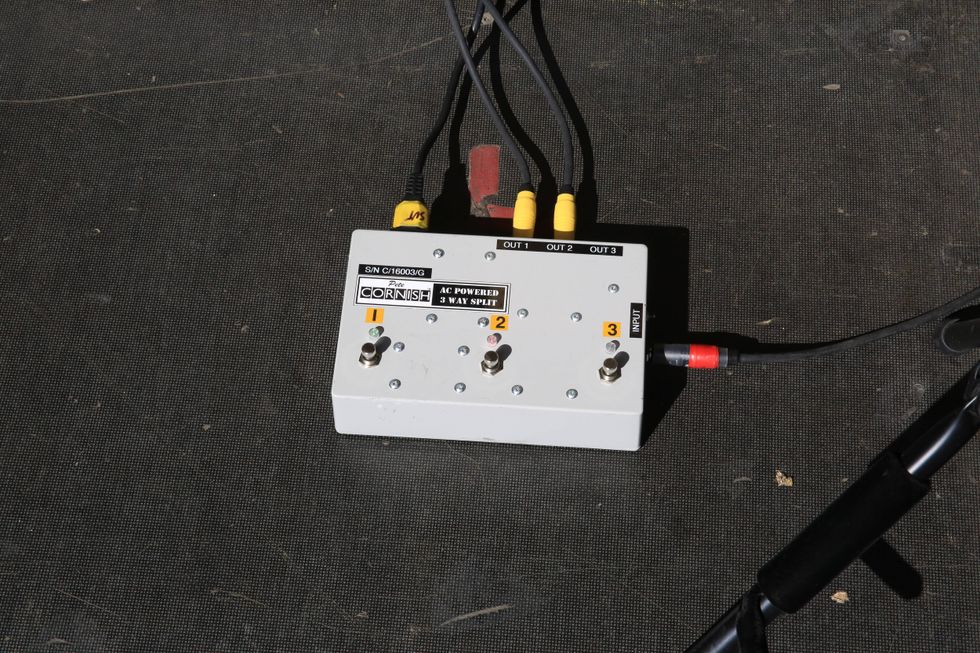

The Death by Audio Fuzz War informed the direction of the story in “Love and Other Forms of Violence” from Diamond Vehicle. Can you tell me how that song was written and the role that pedal played?

Imperioli: Sometimes, we’ll write songs and they’ll come out of jams in practice sessions for ZOPA. That’s all electric obviously. But if I’m writing at home, I’ll either use an acoustic guitar or an electric guitar that my son made that has a Strat body. I’ll just play that and record on my phone. So, that song just started off with a very simple two-chord thing for the verses.

I started practicing that alone in the studio with the Jaguar, and I had just gotten the Fuzz War from Oliver Ackerman who makes them—he’s a friend and a musician I really admire. His band is a Place to Bury Strangers. It’s a great band. I was going to use that in place of the Big Muff and just see what would happen.

I was using the Fuzz War for the rhythm part of these verses, and there was something in the way it fed back in a very weird way. There was this little high frequency that just surprised me. And it happened every time, no matter what amp I would use or what the settings were. But there was something about that, doing the verses cleaner and then doing them with the Fuzz War, and I was like, “Oh, this is what this song is about, light and darkness.” And it just gave me a direction for the chorus.

Our February issue had Stevie Van Zandt on the cover, so talking to you, I’m now thinking about the heavy musical vibe going on in Sopranos casting.

Imperioli: That really comes from David Chase, who in high school was a drummer. He loved music, especially the British bands from the ’60s, like the Stones and the Kinks—like, David was at Altamont to see the Stones. That love of music was definitely infused into The Sopranos. I mean, David at some point thought Steven Van Zandt could be Tony Soprano. He was watching the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductions, and Steven Van Zandt inducted the Rascals. And David loved his speech so much and thought it was so charismatic that he had him audition for Tony Soprano. Stevie was one of the three finalists for Tony Soprano.

At Philly rock club Kung Fu Necktie this winter, ZOPA delivered a fiery performance that ignited the packed audience with a setlist of mostly new material from Diamond Vehicle.

Photo by Nick Millevoi

I’m curious about the intersection between your acting career and your music, and finding time and how you navigate that.

Imperioli: It’s an extension of what I always did. Going back to when I was 20, I was playing in bands and writing and producing plays and directing plays. My wife and I opened this off-Broadway theater in 2003, and I was producing and directing and acting there. So that’s always been my life: writing, directing, acting, producing, film, theater, television, fiction, podcasts, Sopranos podcast….

If it’s something you’re passionate about, you just budget your time to include the important things. That’s all. There’s no formula to it. It’s just that I’m someone who likes to be engaged in things that are creative and exciting to me and find a way to keep doing that.

Is music any more important in your life now than it was before? Have you intentionally foregrounded that?

Imperioli: I think we’ve just gotten more confident. Recording is a big part of that, especially recording the new record. The first album was stuff we had written over the course of six years, and the new album was stuff that was in the last year or two for the most part.

We tend to do best when we play in local places that have a local music scene. Something like Kung Fu Necktie, the band that opened for us, Andorra, is a local Philly band. And in New York we’ve been playing a lot at Baby’s All Right and Mercury Lounge, places where people go to see bands, both local bands and bands that are touring. So, a lot of musicians come to the gig. I love playing clubs that are part of a local music scene.

Sometimes when we’re on the road, if we played a theater that has a very wide variety of touring bands, we don’t do as well. And it’s not as fun as playing at a club that’s part of a local indie music scene.

It connects more, I think.

Imperioli: Exactly. Meeting other bands, playing with other bands that are from similar scenes, it’s been really, really satisfying being part of that.YouTube It

ZOPA perform their two-song Lou Reed medley at Manhattan’s Mercury Lounge, with Imperioli’s phaser set to max swirling, psychedelic effect.

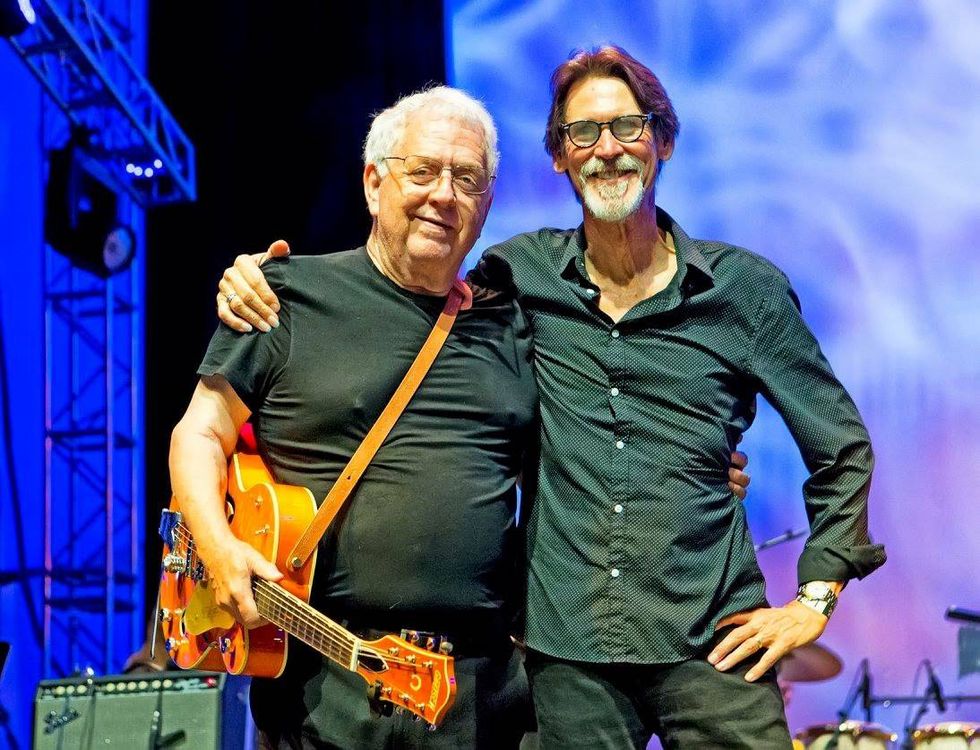

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski