Billy Zoom isn’t particularly sentimental about the impending final chapter of X. Along with day-one bandmates John Doe, Exene Cervenka, and D. J. Bonebrake, the 76-year-old guitarist for the legendary Los Angeles punk band is preparing for one last, long trip out with the group, celebrating their ninth and final album, Smoke and Fiction. And after 47 years in the band, Zoom has earned the right to speak plainly. “This is our retirement fund,” he says of X’s upcoming international tour, which will reach into 2025.

X - Big Black X (Official Music Video)

There are plenty of people, musicians and listeners alike, who will balk at this type of honesty. If someone suggests a band is doing a “retirement fund” tour, it’s typically to accuse them of trying to pad their coffers before calling it quits—as if that’s not something every human in every profession tries to do. As long as we’re still breathing, we all need to eat and pay rent. But for some reason, even as our favorite musicians age, we often don’t like to acknowledge the realities of later years of creative life.

That’s why Zoom’s comment lands as not just a quip, but a genuine assessment of this graceful third act of X’s nearly 50-year career. Smoke and Fiction, the band’s first record since 2020 and just the second since 1993’s Hey Zeus!, is a work that’s keenly aware of its place in time. Lead single “Big Black X” is unmistakably, deliciously X, riding vintage rock ’n’ roll licks and straight-on punk palm-muting. Its lyrics recount scraps and fragments of memories over the decades, like a last-minute, flash-before-your-eyes deathbed recollection. “Stay awake and don’t get taken / We knew the gutter, also the future,” Cervenka and Doe intone in powerful harmony on the chorus. The title of “Sweet ’Till the Bitter End” speaks for itself, and “The Way It Is” is a blunt, artful reckoning with punk mortality: “I know you gotta go / But that don’t make it easier,” the song opens over a mournful rockabilly groove.

X played a hometown show at the Troubadour on June 24, one of a few fond farewells to the place that made them.

Photo by Matt Marble

John Doe was thinking of his musician friends when he wrote that song—some who are still here, some who aren’t. “‘The Way It Is’ was inspired by seeing a lot of our comrades, like Los Lobos and Lucinda Williams and some other people on this Outlaw Country Cruise, realizing that we’re all destined for the end, transitioning,” says Doe. “The line, ‘I know you gotta go, but that don’t make it easier,’ I would say that I was feeling the loss of Dallas Good.” The towering frontman of the Canadian country and rockabilly outfit the Sadies died suddenly in February 2022, at just 48 years old. Doe recorded his 2009 album, Country Club, with the Sadies, and remained close friends with the group. You don’t get to be a cherished rock band for nearly half a century without learning what it means to lose.

To many, it seemed like X had packed it in by the late ’90s, after a compilation record and a farewell tour. Zoom’s departure in 1986 had changed the band, and they wandered further and further from their punk roots—a natural creative exploration that nonetheless hampered their commercial growth. (Zoom allegedly threatened to leave the band in the ’80s if they didn’t achieve greater success, and made good on that promise, returning to the band for their 1998 farewell tour.) Through the early 2000s, X appeared sporadically at festivals around North America, while Doe, Cervenka, and Bonebrake’s country group the Knitters (a wink to Pete Seeger’s folk group the Weavers) put out music and toured. Cervenka and Zoom both battled serious health issues and survived.

Then, in 2017, the year of their 40th anniversary, the band shook awake again for good: The Grammy Museum curated an exhibit on them, the Los Angeles city council declared October 11 to be X Day, and even the Dodgers got in on the festivities, inviting Exene to throw the first pitch and John to sign the national anthem at a home game in August 2017. Three years later in 2020, the band marked another 40th birthday, this time of their landmark debut record Los Angeles, and released their first new LP in 27 years, Alphabetland.

Smoke and Fiction follows that record with a familiar mix of old and new material. Cervenka says that some of her lyrics were culled from poems from 15 years ago. She writes all the time, and keeps everything she works on. It’s not unusual for pieces to go unused until years later, when they find a home in a new context, like a song. “I have boxes and boxes and books and books of writing, so sometimes I’ll just randomly grab a fistful of things and start putting some things together, and see if something from 20 years ago goes with something I wrote today,” explains Cervenka. She and Doe will workshop lyrics over the phone—her in Los Angeles, him in Austin.

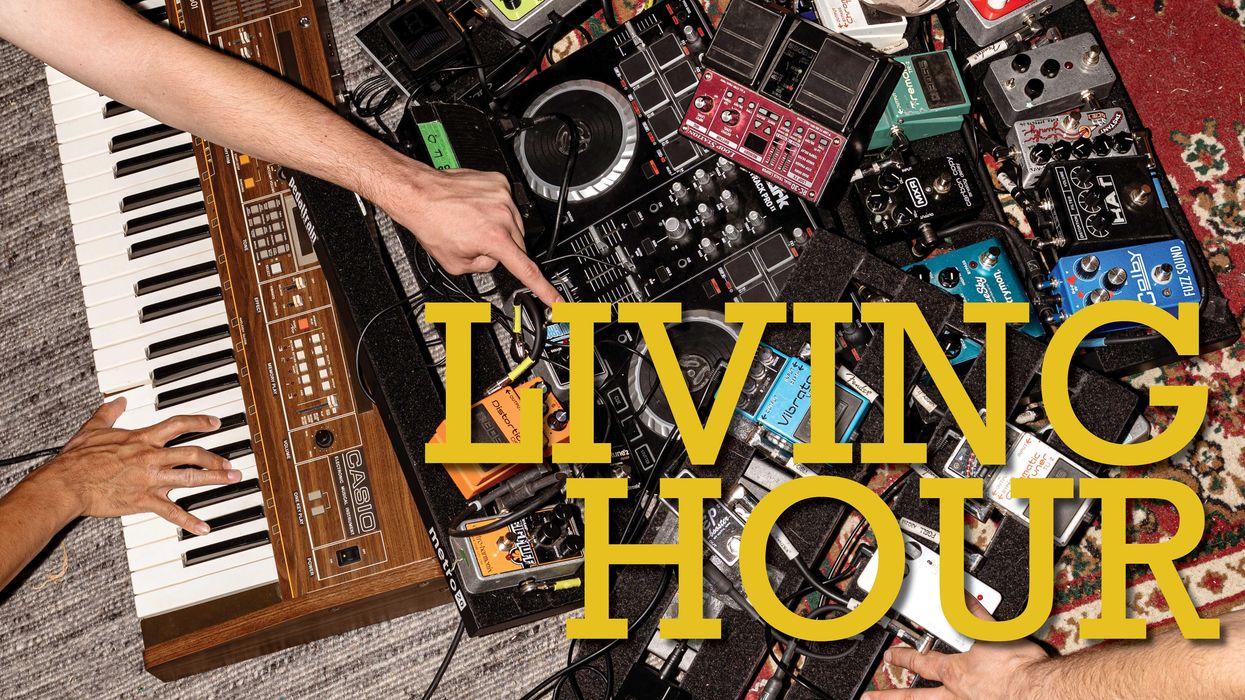

Billy Zoom's Gear

Billy Zoom designs and builds amps and recording gear, and his 10-30 amplifier needed no effects for the new LP’s recording sessions.

Photo by Matt Marble

Guitar

- Gretsch G6122T-59 Vintage Select Edition Country Gentleman with Kent Armstrong P-90 in the bridge, Seymour Duncan DeArmond pickup in the neck, and custom wiring by Billy

Amp

- Billy Zoom 10-30 12-watt RMS combo with one 12” Celestion Vintage 30

Effects

- DeArmond Model 602 Volume Pedal

Strings, Picks, & Cables

- GHS Big Core Nickel Rockers Extra Light

- Dunlop BZ picks

- Hypalon-jacketed Belden 8402 cables with G&H angled plugs

"I was in a little bit of a dark place about 14, 15 years ago,” Cervenka continues. “So some of it is sad, but a lot of it’s good. I love to play with language. That’s my favorite thing about writing, is to do tricky things with words and rhymes. It keeps me really engaged and happy and self-entertained.”

The new record, tracked at Sunset Sound with producer Rob Schnapf, is a defiant, riotous, and often joyful punk-rock ’n’ roll album that somehow still sparks and crackles with all the swagger, poetry, and explosive energy that launched them into the cannon decades ago. According to Doe, it’s just a matter of following your gut. “Intuition is your friend, and your brain is not,” he says. “I’m very proud of the songwriting, the performances, and it wasn’t premeditated, because nothing that we’ve ever done is really calculated. But as it developed, I realized that lyrically it kind of had an overview, and a lot of reflection. Even though I wasn’t really precious about the chords and melodies and things like that, a lot of the songs got reworked. It seems to wrap things up nicely.”

Doe and Cervenka made X known for artful lyrical wordplay from their early days, but they’re also expert storytellers. “Maybe that’s where the crossover is between country-Western and punk rock, and why there’s been a lot of blending of that over the years, because they’re both very simple and elemental,” Doe says. “They’re stories about outsiders or people that don’t fit in, and alcohol and drugs are involved, and dangerous things.” The songs on Smoke and Fiction aren’t all true stories, but there are pieces of their writers in them all the same. “I think all songs are autobiographical somehow, even if it’s just the writer’s participation in some events that they weren’t actually part of,” says Doe. “They have to understand and feel what they’re writing about on some level.”

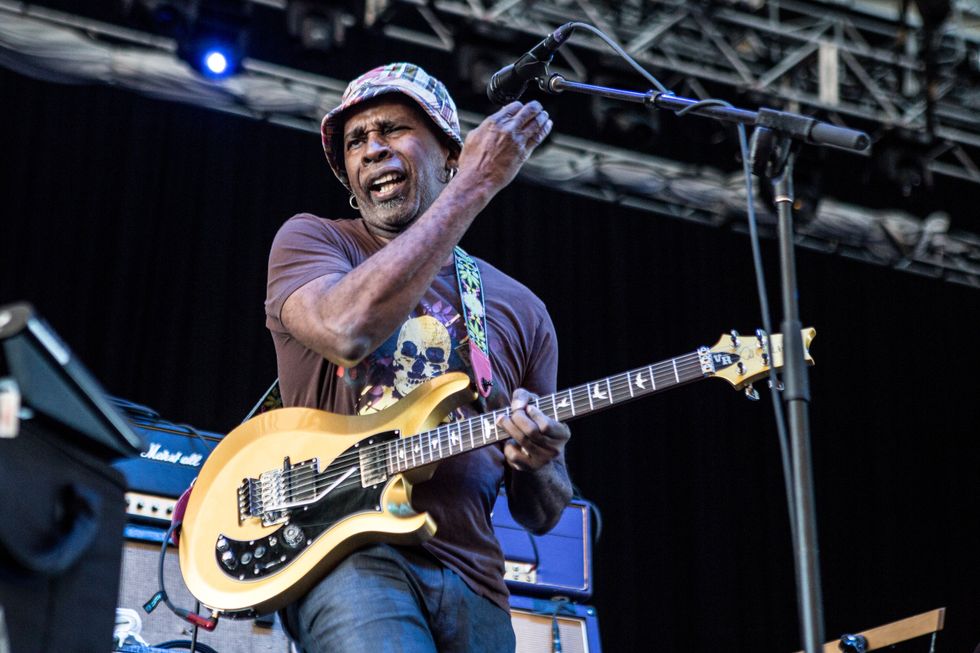

Smoke and Fiction ended up being a retrospective of the band’s career, meandering through the ups and downs of nearly 50 years of punk rock.

Gary Leonard

Zoom, who has designed, built, and repaired amps for decades, recorded his parts for the new LP on the same amp he gigs with: the 2-channel Billy Zoom 10-30 12-watt combo, with one 12” Celestion Vintage 30 speaker. He was initially commissioned to design the amp for G&L Guitars in 2008, but when the market crashed, the design didn’t go anywhere, so Zoom took to using it himself. The normal channel gain goes from 1 to 10, while the “More” channel runs from 11 to 20. Built-in reverb and tremolo add texture and space, and an active midrange control can boost or cut frequencies at 750 Hz. The flexibility meant that Zoom didn’t have to use any pedals on record—the amp spans fat cleans to gnarly, chewy distortion tones, especially with his Gretsch G6122T-59 Vintage Select Edition Country Gentleman, which Zoom modded with custom wiring, a Kent Armstrong P-90 in the bridge, and a Seymour Duncan DeArmond pickup in the neck. Zoom also played Schnapf’s 1960s Epiphone 12-string on “Flipside,” and Zoom’s solo on “The Way It Is” comes courtesy of his Fender Custom Shop Stratocaster with DiMarzio Red Velvet pickups.

Doe, meanwhile, says he recorded on the first real electric bass he ever bought: a 1960 Fender Jazz bass, which is all original except a refinishing, and strung up with Dunlop flatwounds. It’s been with him since roughly 1970. In 2007, he sold it to a friend when he needed the money, but eight years later, the friend sold it back to Doe for the same amount he paid. “It was a beautiful reunion,” says Doe. “It was very emotional.” Doe recorded direct for most of the sessions, but he also made use of an early-’70s Walter Woods amp.

John Doe's Gear

John Doe and Exene onstage: If they could, X would tour forever. But life on the road has a deadline.

Photo by Matt Marble

Basses

- 1960 Fender Jazz bass

- 1967 Ampeg AEB-1 “Scroll” bass

Amps

- 1970s redface Walter Woods Bass Head Amber Light

- Genzler Bass Array2-210-3SLT (for recording and live)

- Ampeg 4x10 (live)

Strings & Picks

- Dunlop flat wound strings (.045-.105)

- Herco Flex 75 picks

These days, Zoom loves designing circuits and prototyping gear, especially recording equipment. “It’s like a puzzle,” he says. “I sit on the couch, watching TV, and I think of something, and I get some graph paper and a pencil, and I draw it out, and I put it in the box. Sometimes I go back and build them, sometimes I don’t. But that’s how it all starts. I always imagine a sound and then I draw the schematic and build a prototype.”

Zoom doesn’t pick up his guitar that much these days. He’s been playing professionally for 61 years—he joined the musician’s union in 1963 at age 15—and the decades of performance have taken their toll. Arthritis, tendonitis, and carpal tunnel syndrome have made playing an excruciating affair. Sometimes, his fingers have gone numb. “You know, in the beginning, I was known for the smile, the grinning,” he says. “And then gradually, the grin turned into gritting my teeth.”

These are the difficult realities of long-term musical life. Now that it’s drawing to a close for the quartet, it’s bittersweet. “I have mixed feelings,” says Zoom. “A little sad, a little relieved. I’m pretty old, though. Touring is getting hard. Dragging luggage through miles of airport, riding hundreds of miles every day, carrying luggage through hotels. I’m getting old for all that. But I will miss the audience.”

Cervenka feels the same way. “We’re in and out of vans and the Holiday Inn Express,” she says on the way to a gig in St. Louis. “It’s not just, ‘Oh, we can’t play anymore.’ We can play. We played last night, it was great. And if that’s all we did, was magically appear on stage, it’d probably go for a couple more years. But it’s not easy. I would tour forever if I could. After we’re finished touring, I’ll probably just ride around and go to all the places I couldn’t spend enough time in.”

Bitter End - Smoke & Fiction-"X"- at the Warfield Theater, SF - Dec 30, 2023

Last December, X treated fans at San Francisco’s Warfield Theater to unreleased tunes from Smoke and Fiction, including “Sweet ’Till the Bitter End” and the title track. Check them out on this DIY capture.

Post X, Cervenka expects that she and Doe will continue to perform as a folk duo, plus she’ll have more time for her visual art. Doe plans to keep releasing solo records, and Exene remains his favorite singing partner. “We have a secret language,” he says. “We just get each other singing. It’s a beautiful thing.”

It’s been more than 40 years since the abrupt, jagged main riff of “Los Angeles” changed punk music forever. The members of X have gone through life’s ringer, and emerged the other side, arm-in-arm, four punks and friends making sense of a weird world. They’ve had a good run. It’s time to look back and take stock. “We were really brave and crazy and stupid and we survived, and you can, too,” says Cervenka. “You can have fun and look back on your life and go, ‘Wow, I did that. That was crazy.’”

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)