The Fender Stratocaster is perhaps the most popular electric guitar of all time. So why have so many people altered the pickup design since the instrument’s 1954 debut?

Many players—even Strat fanatics—have a love/hate relationship with the guitar’s pickups, and pickup modifications are almost as old as the model itself. The pickups in early models employed alnico 3 magnets, but louder, brighter alnico 5s became standard within a few years. Subsequent departures include higher-output bridge pickups for fatter, less shrill lead tones, hum-cancelling designs, and non-staggered magnets to accommodate modern string tastes and flatter neck radiuses.

Still, many players swear by the original design, and for this roundup, we went the ultra-vintage route. We asked participants to submit period-correct pickup sets based on these criteria:

• Traditional materials and structure.

• Traditional number of winds.

• Alnico 5 magnets.

• Formvar-coated wire. (Formvar is the resin film that insulates the copper wire on traditional Strat pickups.)

• Staggered magnets—that is, magnets of varied height in relation to the strings, as found on vintage Strat pickups. (Whether staggered magnets are desirable for modern players is a subject in itself. See the “Is It Better to Stagger or Be Straight” sidebar.)

There really isn’t much to a Strat pickup: just coated copper wire, a bobbin to wrap it around, six little magnets, and the insulated wires that link the pickup to the guitar’s circuitry. Yet there’s much room for variation within those narrow parameters. Extra winds of wire produce a hotter pickup. Degaussing (demagnetizing) the magnets yields a softer, smoother tone reminiscent of an old pickup. Different grades of alnico yield different tones. Even two “strictly vintage” pickups can sound quite different.

Players seeking vintage Strat pickups have many options—far more than covered here! When selecting participants, we chose companies not represented in our last major pickup roundup, which included models from DiMarzio, Fralin, GFS, Gibson, Harmonic Designs, Lollar, and Seymour Duncan. This time around, our lovely contestants are from Fender’s Custom Shop and four smaller companies: Amalfitano, Klein, Manlius, and Mojotone.

Spoiler Alert

Might as well say it up front: I like all five of these sets. That may sound like a timid editor scared of making enemies, but it happens to be true. Each is lovingly handmade from quality, period-correct materials. If you passed me an old Strat with any of these beneath the pickup covers and told me they were original, I’d have no reason to doubt you. I’d perform and record with any of these sets without hesitation. Every single pickups sounds authentically “old Strat,” and any of these sets would provide a major upgrade for, say, an entry-level Fender Squier Stratocaster or inexpensive Strat-style guitars from other manufacturers.

Each set looks authentically vintage, from the period-correct bobbins to the wax-coated cloth push-back wire. In fact, I don’t even discuss physical appearance in the individual write-ups. Same with the workmanship—every pickup appears perfectly well made, which is why each set receives an identical build-quality rating.

Still, there are meaningful variations between models, and with luck, my observations can steer you to the model that best suits your needs and tastes. But don’t expect us to declare which model sounds the “most vintage.” Like much music gear from a half-century ago, old Strat pickups are like snowflakes: No two are exactly alike.

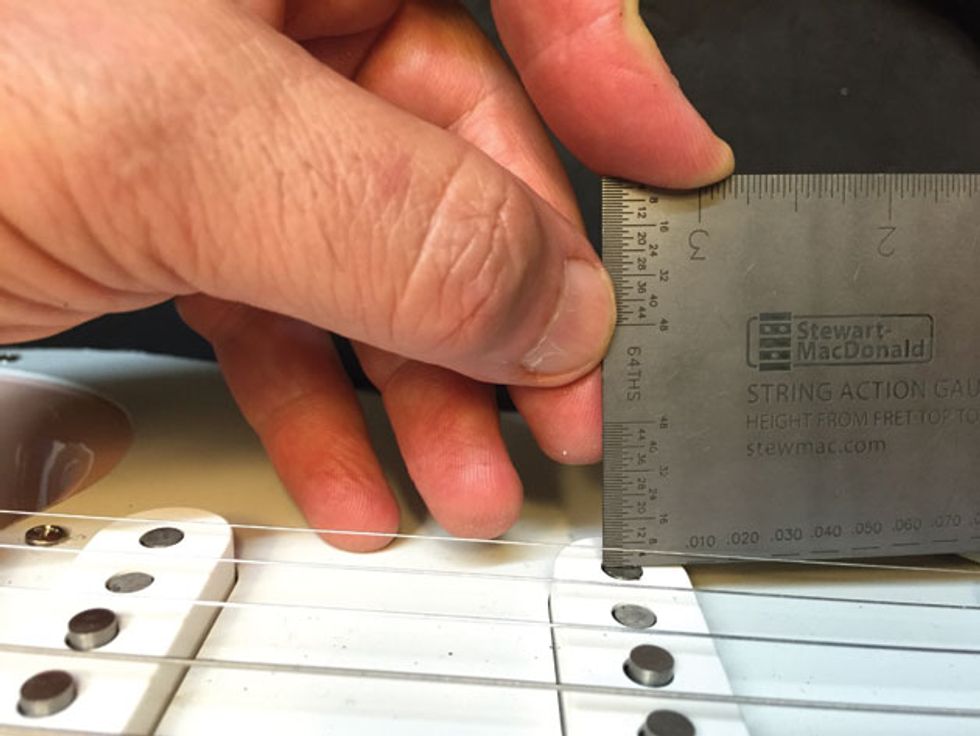

All pickups were tested at equal height, thanks to the ever-useful Stew-Mac string action gauge.

Testing Procedures

I removed as many variables as possible while testing. I auditioned and recorded every pickup in the same instrument: a shell-pink American Vintage ’56 Stratocaster with a one-piece maple neck. I set pickup height according to Fender’s official recommendations (6/64" on the bass side with the 6th string pressed against the 21st fret, and 5/64" on the treble side with the 1st string pressed against the same fret). The test guitar has a vintage-style 7.25" fretboard radius. (Many modern Strats have flatter radiuses, or even compound ones, which makes a big difference in relative string volume when combined with traditional staggered-magnet pickups, as discussed in the “Is It Better to Stagger or Be Straight?” sidebar.)

You’ll hear all five pickup-selector positions for all five sets. I concocted a short demo piece for each pickup-selector position and used the same music for each set. All these clips employ clean sounds because these most clearly reveal variations between models. But to paint a fuller picture (and relieve the monotony), there’s also a dirty clip for each set. Here I didn’t try to match performances: I just plugged into a homemade, vintage-correct Fuzz Face clone—fully cranked—and merrily wanked away. In each case, though, the distorted clip starts in position 5 (bridge pickup alone) and then switches to position 1 (neck pickup alone).

Likewise, the recording setup was identical for every pickup. I tracked all the clean clips directly into Logic Pro via a Universal Audio Apollo interface with no compression, EQ, or other effects. Input settings never varied. After all the clips were captured, I reamped each one through a Carr Skylark amp (a 12-watt, 1x12 combo amp inspired by Fender’s vintage small-format amps) in a single session. All controls were at noon and never budged. The mic was a Royer R-121, a sweet-sounding ribbon model. The mic position remained constant. Meanwhile, the dirty clips were played directly into the amp without reamping, using the same setup as for the clean sounds.

String choice is a major tonal factor, especially with staggered-magnet Strat pickups. While I was tempted to go full vintage with a period-correct set of heavy-gauge flatwounds, it seemed wiser to install a roundwound set closer to what most modern players use (though I kept things a bit vintage with an all-nickel DR Pure Blues Nickel Heavy set gauged .011–.050).

But to illustrate how staggered-magnet pickups sound with the sort of strings they were designed for, I also recorded an all-original ’63 Strat with a high-end Thomastik-Infeld flatwound set. (See the “Is It Better to Stagger or Be Straight?” sidebar.) But I didn’t compare the new pickups directly to the ones in the old Strat because there are too many other variables at play: dry old wood, a rosewood fretboard, ancient hardware, worn finish, etc.

Other Considerations

A few more things to keep in mind while comparing pickup sounds:

• While I tried to play the demo parts as consistently as possible, there’s inevitably some variation between performances.

• Some sets come with pickup covers. Some don’t. But it’s not a big deal. If you’re retrofitting a Strat, you already have usable covers. If you desire a unique look or a color that matches an antique-looking pickguard, a stock white cover won’t help. Strat pickup covers are available in many colors, and they’re cheap—prices range from two to four dollars per cover.

• Each pickup review includes a DC resistance value, expressed in ohms. More coil winds mean more output, a hotter pickup, and a higher DCR number. There isn’t a vast range of values among the 15 tested pickups—the lowest-output one is 5.68k (that is, 5,680 ohms), while the hottest is 6.48k. Modern “overwound” Strat pickups can be far hotter: the DCR of a DiMarzio Virtual Vintage Solo is 11.17k, while the Seymour Duncan Custom Flat Strat delivers a walloping 13.3k. But even relatively small differences can be audible. We’ve included two sets of DCR values: the ones advertised, and the actual bench measurements. (That’s not to imply that anyone is being dishonest—minor unit-to-unit variation is expected.)

• Finally, be aware that pickup makers tend to be exceedingly customer-oriented. Some small companies wind to order, and even the large ones have custom shops ready to customize on request. You might ask for higher output, a different magnet type, or staggered magnets instead of straight ones, and vice-versa.

Strat’s All, Folks!

There are no losers here. Every time I switched sets, my gut reaction was, “Damn, that sounds good!” Listening back later to the test recordings only reinforces that impression.

There are many fine vintage-style Strat replacement pickups to choose from, and these five are but the tip of a massive iceberg. A couple of these sets are closest to my heart, but if another player had written this up, others might easily have come out on top. The colors vary, but the quality doesn’t.

Thanks to Fender’s Jason Farrell for loaning us our cool test guitar.

So enough preamble. Let’s hear some cool pickups!

Amalfitano Custom/Vintage Strat Set

DC resistance:

- Bridge: 6.7k (advertised), 6.48k (measured)

- Middle: 6.3k (advertised), 6.33k (measured)

- Neck: 6.3 (advertised), 6.24k (measured)

To hear each pickup position alongside the other reviewed models, see “Five Pickups, Side by Side.”

Amalfitano is a perfect example of a customization-friendly shop: Jerry Amalfitano’s stock vintage Strat trio, the ’62 Set, employs alnico 3 magnets, as did the earliest Strats. But when we requested an alnico 5 set for review, he quickly made one, and he assures us that any customer can make similar requests. (The Custom/Vintage set heard here is the only entry in this roundup that’s not a stock item.)

These are bold-sounding pickups with uncommonly powerful lows and intense upper-midrange presence. Like many Strat pickups, they can be a bit edgy when playing clean in position 1 (bridge pickup alone), but bountiful lows balance that upper-mid bite. That 2 kHz edge pays dividends in other ways: positions 2 and 4 have a gorgeous airy quality, while distorted notes maintain a crisp attack. There’s nice, zingy sustain at all settings.

This is the highest-output set tested—and at $100 per pickup, the most expensive.

Ratings

Pros:

Excellent definition clean and distorted. Hefty lows. Beautiful combined-pickup tones.

Cons:

Pricy.

Street:

$300

Amalfitano Custom/Vintage Strat Set

amalfitanopickups.com

Tones:

Versatility:

Build/Design:

Value:

Fender Custom Shop Custom ’54

DC resistance:- Bridge: 6.5k (advertised), 6.43k (measured)

- Middle: 5.9k (advertised), 6.21k (measured)

- Neck: 5.9k (advertised), 6.05k (measured)

To hear each pickup position alongside the other reviewed models, see “Five Pickups, Side by Side.”

If you averaged together every vintage Strat pickup, you might wind up with something like Fender Custom Shop’s Custom ’54s. They’re not too bright … not too bassy … not too hot … not too timid … and not too eccentric. They’re quintessentially Strat.

Tones are straightforward but attractive. Unlike some of these sets, Custom ’54s have no big bass bump and no particularly prominent treble frequencies. The bridge pickup is edgy at clean settings, as you’d expect from a traditional Strat. Positions 2 and 4 are relatively muted, yet they maintain a pretty sparkle. There’s no unwanted “woofiness” to the neck pickup—a scoop centered around 150 Hz keeps things clear without surrendering too many lows. Distorted lead tones are bright, but not brittle.

The Custom ’54 set sounds exactly how you’d expect a solid vintage-style Strat set to sound—and that’s precisely what many players desire. And at $199 per set, they’re an excellent deal.

Ratings

Pros:

Textbook vintage Strat tones. Great neck pickup clarity. Nice price.

Cons:

Too conventional for some?

Street:

$199

Company

fendercustomshop.com

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Klein Epic Series 1959

DC resistance:- Bridge: 5.8k (advertised), 5.76k (measured)

- Middle: 6.0k (advertised), 5.86k (measured)

- Neck: 5.9k (advertised), 5.76k (measured)

To hear each pickup position alongside the other reviewed models, see “Five Pickups, Side by Side.”

According to his website, pickup maker Christopher Klein went to phenomenal lengths to create the Epic Series 1959: “We started by buying an original 1959,” he writes, “then we destroyed that pickup and sent the magnets to an independent laboratory to have the chemical composition analyzed to find out what proportion of elements comprise that magnet.” He claims similar obsessiveness with other construction detail as well.

I have no idea whether to credit research or a great ear, but the Epic Series 1959 set is simply magnificent. You know how most vintage Fenders sound great, but some sound magical? This set can probably nudge most guitars in that magical direction.

The Epic 1559s don’t sound odd in any regard—their tones are très Fender. Yet they just feel a bit more musical than most Strat pickups I’ve encountered. The neck pickup has plenty of treble snap, but there are no nasty spikes and just the right amount of compression—you can dig in hard on clean bridge tones without puncturing eardrums. The neck pickup sounds warm, but never woolly. The combined settings deliver the expected “hollowness,” but with uncommon fullness of tone. There’s great sustain—everything just sings. Note fundamentals are always solid—even bright settings have heft. And when you slather on the gain, chords and single-notes maintain great balance and definition.

Interesting detail: Most modern Strat sets—boutique and otherwise—employ a slightly hotter pickup in the neck position. With ’50s and ’60s Strats, it was luck of the draw—they just dropped in pickups without scaling their relative output. In this case, the middle pickup is the hottest. Is there a lesson here?

Ratings

Pros:

Superb tones in every setting. Neck pickup is bright, but never brutal.

Cons:

None.

Street:

$245

Klein Epic Series 1959 Set

kleinpickups.com

Tones:

Versatility:

Build/Design:

Value:

Manlius Vintage 62

DC resistance:- Bridge: 6.3k (advertised), 6.25k (measured)

- Middle: 6.2k (advertised), 6.11k (measured)

- Neck: 6.1k (advertised), 6.15k (measured)

- Bridge: 5.78k (advertised), 5.68k (measured)

- Middle: 6.12k (advertised), 6.22k (measured)

- Neck: 5.78k (advertised), 5.68k (measured)

To hear each pickup position alongside the other reviewed models, see “Five Pickups, Side by Side.”

Vintage 62 is a traditional-sounding set boasting attractive, articulate tones. The bridge pickup has the expected spank, but with relatively even treble response and no sore-thumb spikes. The neck pickup’s voice is slightly on the dark side, but in a good way—there’s enough snap to maintain strong note attack, and it provides an especially dramatic contrast to the bridge tone. There’s lovely, acoustic-like openness in position 2 and lush warmth in position 4. Distorted sounds strike a fine balance between fat and snappy. It was a blast playing them through a vintage Fuzz Face.

The Vintage 62 is the only set here with a reverse-wound, reverse-polarity (RW/RP) middle pickup. This wasn’t a feature on vintage Strats, but many modern players favor the arrangement because it provides humbucker-style noise cancelling in the combined-pickup settings. That’s a nice feature—if you play a venue with unusually awful wiring, you can survive by favoring positions 2 and 4. Some say a RW/RP middle pickup provides more “quack,” though I don’t perceive it here. Most pickup companies offer both standard and RW/RP middle pickups. (We probably should have requested non-RW/RP pickups for consistency’s sake, but—um—I forgot.)

This is the least expensive set here. It’s a steal at $180.

Ratings

Pros:

Excellent tonal range. Badass overdriven sounds. Great price.

Cons:

None.

Street:

$180

Manlius Vintage 62 Set

manliusguitar.com

Tones:

Versatility:

Build/Design:

Value:

Mojotone ’59 Clone

DC resistance:To hear each pickup position alongside the other reviewed models, see “Five Pickups, Side by Side.”

Would you like your Strat to sound the way it did in music stores in 1959? Or would you prefer it to sound like the same guitar 56 years later? If you favor the aged sound, Mojotone’s ’59 Clone may be the set for you.

All the sets covered provide authentically vintage tones, but no other sounds this old. A pickup’s tones tend to smooth out over time, largely due to weakening magnets. I have no idea whether Mojotone systematically degausses (demagnetizes) their magnets, but it sure sounds like it. Every settings is as rich, warm, and as smooth as decades-aged whiskey.

The result isn’t for everyone—this is the quietest of the five sets. It’s also the one with the most restrained treble attack, so it might not be the best choice if you prefer Strats that sizzle. But if you dig the mellowed warmth of a well-loved old axe, here you go! The instant I popped these into our test guitar, the instrument felt decades older. (And as on the Klein set covered above, the middle pickup, not the bridge, is the hottest. Food for thought?)

This set is a great choice if a bright Strat bridge pickup makes you flinch. Here, position 1 isn’t spanky/snappy—it has more of an open, acoustic-guitar-like character. Settings 2 and 4 don’t sparkle as much as on some of the other sets, but they offer lovely, burnished tones you can listen to for hours. The tones aren’t dark, exactly—“rounded” and “warm” are better adjectives. Same with the distorted sounds: they’re less pointy and aggressive than on the other pickups. If Strat pickups were cats, the other sets would snarl. This one purrs.

The ’59 Clone set may be too restrained for some. But for those who appreciate the deep, baked-in character of old guitars, this set is the one to beat. At $212, they’re a bargain.

Ratings

Pros:

Authentically “old-sounding.” Rich, nuanced tones.

Cons:

Not for those seeking snappy, aggressive tones.

Street:

$212

Mojotone ’59 Clone Set

mojotone.com

Tones:

Versatility:

Build/Design:

Value:

On vintage Strat pickups, the greatest height discrepancy is between the 2nd- and 3rd-string magnets, as seen on this modern Fender Custom Shop model.

Is It Better to Stagger or Be Straight?

Many modern Strats have “straight” pickup magnets—their height is more or less equal. Meanwhile, Strat pickups from the ’50s and ’60s (and vintage-style replicas like the sets covered here) have magnets of uneven height. The middle pair is closest to the strings, while the 5th- and 6th-string magnets are further away. The most dramatic variation is between the 2nd- and 3rd-string magnets. The former is furthest from the string, often as low as the bobbin itself, while the latter is usually tied for tallest.There’s a good reason for this arrangement, or at least there used to be: It provided the best volume balance between strings. But back when the Strat pickup was designed, most players used heavy flatwounds with a wound 3rd string. To illustrate how a Strat would have sounded back in the day, here are some clips of an all-original 1963 model strung with big flatwounds and a wound G:

I happen to dig that sound, but it’s just not how most modern players roll. Today’s guitarists favor lighter-gauge roundwounds with an unwound 3rd for easy string bending and louder, brighter tones. Also, few modern strings are pure nickel like the ones from 60 years ago (though light-gauge, pure-nickel roundwounds are available if you’re willing to pay a bit extra). Straight magnets are likelier to produce even string volume with such modern strings.

So only weirdos who love fat flatwounds should use staggered magnets, right?

Um, no. Since the mid ’60s, countless players—everyone from Hendrix to Clapton to Gilmour—have strung staggered-magnet Strats with light roundwound sets and unwound 3rd strings. To many listeners, the resulting tones are simply how a Strat is meant to sound. (And whether they realize it or not, good players who use this recipe are almost certainly adjusting their attack from string to string to balance levels.)

In recent years, there’s been another wrinkle: flatter fretboard radiuses. (The more inches, the flatter the fretboard: 7.25" is curvier than 10".) A flatter neck brings the inside strings even closer to the middle magnets, and the D and G strings can be too loud. (Though again, sensitive players tend to compensate via touch.)

So what’s the best option? Duh—try both and see which you prefer! But as a crude rule of thumb, use staggered magnets if you worship the tones of the classic-rock Strat masters, but go straight if your guitar has a modern fretboard with a flatter radius.

Are Strat Positions 2 and 4 Out of Phase?

Try this on any guitar forum: Refer to pickup position 2 and 4 as “out of phase” and someone will promptly inform you of your ignorance. But are they right?

It depends whether you ask an electrical engineer or an acoustician. True, the two-pickup settings on a Strat are not electronically out of phase in the way that, say, Jimmy Page wired his Les Paul to provide a true out-of-phase sound. (It’s a thin, strangled tone that you probably wouldn’t use much anyway.) So the electrical engineers have a point.

On the other hand, the “hollow” timbre we associate with positions 2 and 4 is precisely due to audio phase cancellation. You get a comparable result when, say, you track an acoustic guitar with two closely placed mics: a notched, almost phasey sound stemming from some, but not all, frequencies being out of phase between one listening point and the other. The distinctive tones of positions 2 and 4 are due to acoustic out-of-phaseness.

So peace, man—you’re both right. (Though you hold the moral high ground for not being a dick.)

Five Positions, Side by Side

This article is laid out so that you hear the five pickup-selector positions for each set on their own. But for ease of comparison, here are the same demo clips organized by position, not manufacturer.Position 1

Position 2

Position 3

Position 4

Position 5

Dirty

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)