“Think about the American and British rock bands trying to get into the Cold War Soviet Union to play rock music that Soviets had never heard—through their British tube amps, with tubes manufactured in Russia.”

That quote, from Sweetwater Senior Category Manager for Amps and Effects Darren Monroe, sums up how much culture and politics can impact every note you play. And that’s especially true regarding tubes. Let’s start with some deep background.

A Brief Post-War History of Tubes

Until the mid-1950s, the vacuum tube ruled the world of electronics. If something needed amplifying, there were countless high-quality variations to choose from. They were in TVs, radios, record players, etc. The world’s armies even got into the game, demanding military-spec options that continue to be among the most sought-after tubes today. So, the little glowing bottles were in high demand, and the industry thrived. But things were about to change.

Seemingly overnight, the solid-state transistor became the go-to platform for countless electronic products we still use today, literally changing the world. They were cheaper to make, smaller, more efficient, and more reliable. They also offered pure, uncolored sound—precisely what you want in a great stereo system.

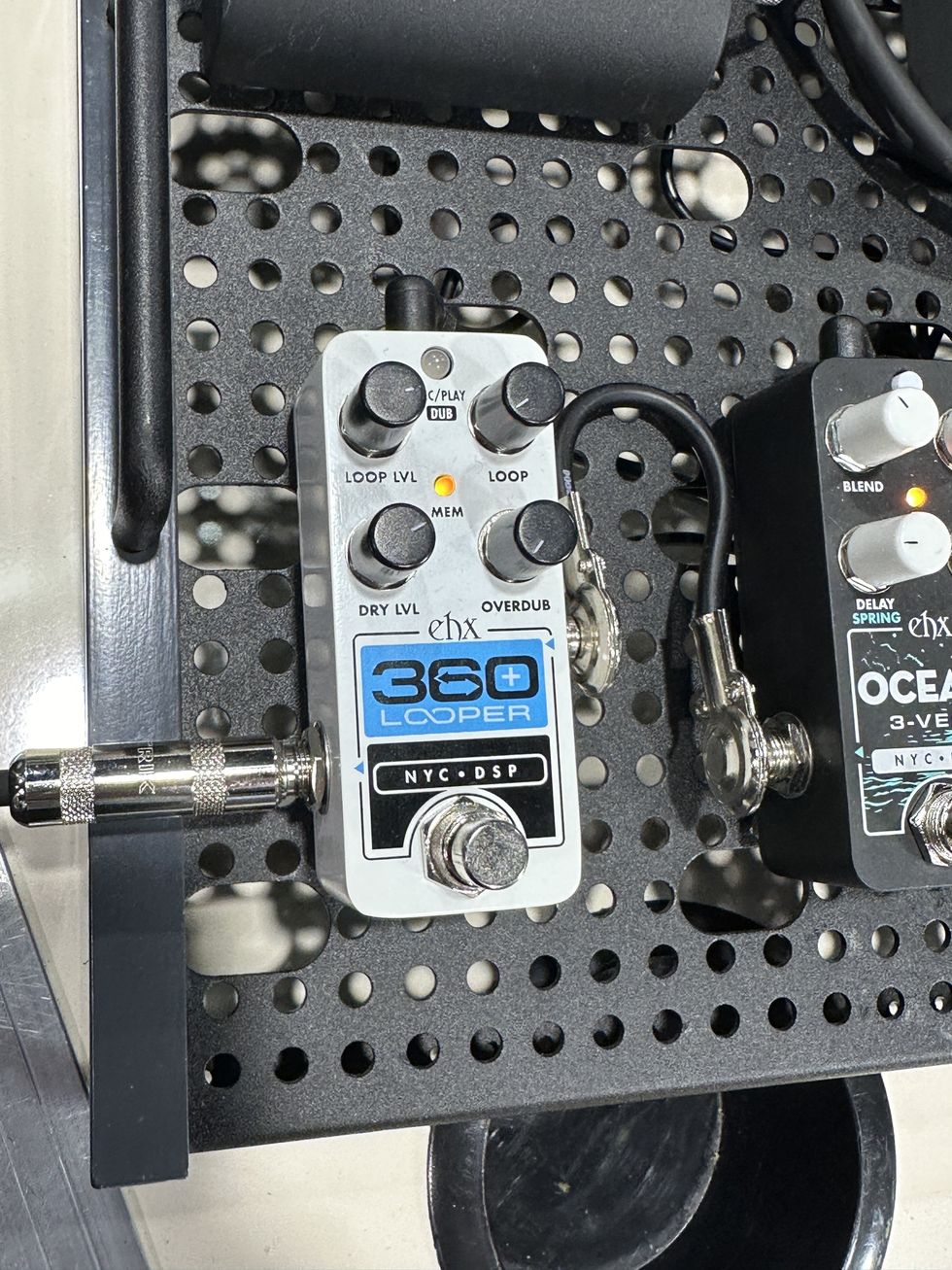

Mike Matthews, the founder of Electro-Harmonix, had the foresight to acquire tube manufacturers, starting in the early 1990s, and today the brand names Tung-Sol, Electro-Harmonix, EH Gold, Genalex Gold Lion, Mullard, Svetlana, and Sovtek are all under the company’s umbrella.

Photo by Mike Chiodo

The First Tube Shortage

The demand for vacuum tubes dried up quickly. Factories that used to produce thousands of tubes daily had to close their doors as they watched orders disappear. Tube manufacturers all but vanished entirely from the U.S. Of course, guitarists still wanted their tubes, but, as Dave Friedman, owner/designer of Friedman Amplification, explains, there weren’t nearly enough 6-stringers to keep the giant industry afloat.

“The guitar tube market is really small in the scope of the tube industry,” he says. “Tubes used to be used in a variety of things, so these huge factories [suddenly] had no demand. They basically became obsolete. That’s when Mike stepped in.”

Friedman is referring to Electro-Harmonix Founder and President Mike Matthews. A legend in the musical instrument industry, Matthews helped write the template for many electric guitar effects pedals. His iconic designs—including the Big Muff, the Memory Man, the Electric Mistress, and the POG—are still going strong today. But many guitarists don’t know that Matthews is a massive presence in the world of vacuum tubes for guitar amplification, and helped save the industry.

It all started with the crumbling Soviet Union. “I took a rock ’n’ roll band to Russia in ’79 for the first exhibit they opened to companies around the world for consumer products,” Matthews recalls. “Only two companies from the U.S.A. went: us and Levi’s. And when I was there, I started thinking about how I could buy products from Russia [to import in the U.S.].”

“The EL34 everyone was using was the German Siemens tube. And in ’90 or ’91, those tubes went away. There were no other EL34s being made.” —Dave Friedman, Friedman Amplification

With his background in effects pedals, Matthews was familiar with integrated circuits (ICs), and dove head-first into importing Russian versions at 15 cents each. He says he made “a killing on them!” But it was only a short time before another trip east, and a respected friend’s approval, inspired the switch to importing tubes.

“In ’88, I saw vacuum tubes on the wall at the Ministry of Electronics [the Soviet Union’s state-run organization responsible for research, development, and production of electronic and electrical devices, from 1965 to 1985]. I took samples to Jess Oliver [famed amplifier designer and former vice president of Ampeg], and he said, ‘They’re good!’ So, I got early customers like Peavey, and the tubes took off!”

But the U.S.S.R. was failing, and panicked Soviet authorities demanded he commit big or leave it all behind. “Because the Soviet Union was starting to fall apart, the companies that made the tubes defaulted on their loans,” he explains. “So, the Russians told me that either I had to buy the factory for $500K or they’d sell to Groove Tubes. So, I sorta had to buy it.” And then he was in the vacuum tube manufacturing business for good.

“It has been a big deal,” says Sweetwater’s Darren Monroe. “In some cases, we even had to take products off the web.”

Building Back the Biz

The early ’90s were another dark time for the vacuum tube industry. Though Matthews was hard at work building his tube operation, he was far from full-strength, and other tube manufacturers continued to disappear. It got so bad that many of the day’s most famous amplifier designers adapted their amps for whatever tubes were available.

Friedman remembers, “When I started in the industry in ’88, Sylvania tubes were around but coming to an end. The EL34 everyone was using was the German Siemens tube. And in ’90 or ’91, those tubes went away. There were no other EL34s being made. Mike Matthews was just starting, so for a short time, everyone switched to the Sovtek 5881, which was a Russian military tube. Even Marshall had 5881s in their amps. EL34s didn’t exist!”

Thankfully, there was hope. As Matthews’ tubes were coming online, Svetlana (who would later be purchased in 2001 by Matthews under the name New Sensor Corporation) emerged as a player in the tube game.

Then came tubes from China. “Slowly, Svetlana came out, Mike came up, and then some Chinese EL34s showed up,” recalls Friedman. Availability stabilized with the entry of Chinese mega-manufacturers Shuguang and Psvane in the international marketplace. In Russia, Matthews grew to absorb the brands Tung-Sol, Mullard, and Sovtek, too. Also, newcomer JJ Electronic showed up in the early ’90s. They earned a name for quality and reliable tubes made in Czechoslovakia, and, after the division of that country, Slovakia.The world now had sufficient vacuum tube manufacturers to furnish guitarists, amp builders, and retailers everywhere. For nearly 30 years, you could get almost any tube from countless retailers and distributors. That changed in 2020.

“At the end of 2019, the Chinese government told Shuguang, ‘we’re closing you down.’ To make things worse, I don’t know if they will be able to open again. They lost all of their skilled workers.”—Mike Matthews, Electro-Harmonix

The Current Shortfall

If you’ve shopped for new tubes in the last couple of years, you might have noticed strikingly few options available, and even more striking price tags on some of the ones that were. Yes, the current tube shortage is real. Guitar amp builders and retailers haven’t been able to rebuild their stock of tubes.

Why? The current shortage began in late 2019/early 2020, when China’s Shuguang factory—then the world’s largest tube manufacturer—shut its doors seemingly overnight. The loss of Shuguang put the tube industry on its heels in a big way, plus the pandemic was looming right around the corner.

“That was big,” acknowledges Matthews. “At the end of 2019, the Chinese government told Shuguang, ‘We’re closing you down.’ To make things worse, I don’t know if they will be able to open again. They lost all of their skilled workers.”

Very few in the industry know the real reason Shuguang was shuttered. Still, with the Chinese government’s penchant for secrecy, theories abound. According to Matthews, the Peking government wanted the factory’s land. Friedman, though skeptical, heard a different story. “They had a fire a while back, but who knows if they were lying,” he says. “Anyway, their whole process still isn’t back. Right now, there is only New Sensor Corporation, JJ, and Psvane. Those are the only manufacturers [although their tubes are sold under many brand names]. So, all your tubes are only coming from three sources."

“The guitar tube market is really small in the scope of the tube industry,” says Dave Friedman. “Tubes used to be used in a variety of things, so these huge factories [suddenly] had no demand. They basically became obsolete. That’s when Mike stepped in.”

Fast forward to today, and the world continues to deal with Covid, labor shortages, international tensions, and all-out war. Varying government ideologies snarl and confuse the production of countless products, and importing and exporting of many products has ground to a halt.

While the Russia/Ukraine war and its political ramifications haven’t officially stopped Matthews and Russian tube production, they have introduced nearly insurmountable challenges to his ability to export goods. Matthews believes this explains the massive price increases, noting, “Western countries have high tariffs on things from Russia, so the costs are up.”

“A tube that used to wholesale for $9 now wholesales for $18,” adds Friedman. “Some 12AX7s are selling at retail for $30 or something! The wholesale side is not much less than that. Russian tubes are kinda off the table at this point.”

The two vacuum tube manufacturers that remained open for business with no limitations were JJ Electronic and Psvane. But both have struggled to keep up with demand. It got so bad that, according to Friedman, “JJ were so back ordered that they hadn’t taken any new orders for a couple of years.”

“A tube that used to wholesale for $9 now wholesales for $18. Some 12AX7s are selling at retail for $30 or something! The wholesale side is not much less than that.”—Dave Friedman, Friedman Amplification

Tube Supply Today

The tube shortage has weighed heavily on the entire guitar industry for a couple of years now. Labor shortages and trade tariffs are a major headache for tube manufacturers, amp builders can’t finish their products, and guitarists can’t keep their amps in working shape. Much of this comes to a head at music retail.

“It has been a big deal,” Sweetwater’s Monroe says, sighing. “In some cases, we even had to take products off the web. There was no way we could deliver. We even explored buying a container full of tubes and getting our own tube-matching equipment. But that was such a huge task that we decided not to do it.”

For large retailers, the problem is twofold. They must have after-market tubes for their customers. Plus, they understand the need to allocate tubes to amp manufacturers, ensuring the tube shortage doesn’t also become an amp shortage. If tube amp builders don’t have tubes, they’re out of business.

“It’s a difficult needle to thread,” Monroe says. “There are a lot of tube amp users out there that need to service their existing amp. We can’t provide that because all the tubes are going to new amps. Yeah, we want to sell more amps but, at the same time, we want to take care of those customers.”

According to Mike Matthews, making tubes in the U.S. "“would cost something like 500 to 600 percent more. The environmental and labor considerations…. It’s a handmade business, and the costs are just way too high.”

Photo by Mike Chiodo

The Cost Factor

Other than JJ Electronic, nearly every vacuum tube today originates from Russia or China. In the ’70s and ’80s, both were promising markets on the global stage. But today, both countries have volatile political climates and have economically distanced relationships with the U.S. that makes trade, including the tube trade, much more difficult and expensive. So, many guitarists in our hemisphere are asking, “Why not just make tubes here in North America?”

Matthews wades in: “You can’t make them in the U.S.A. It would cost something like 500 to 600 percent more. It’s just much too expensive. The environmental and labor considerations…. It’s a handmade business, and the costs are just way too high.”

With the U.S. being a no-go, what about other industrialized countries that manufacture high-quality products while still keeping costs down? Could we produce tubes in Mexico, Indonesia, or Taiwan?

Again, Matthews says no. It’s just too skilled-labor intensive. “It’s a handmade thing. A machine can’t just make the whole tube,” he explains. “There are a lot of different parts that go into one tube. Each of those parts is made separately; then, the whole tube is put together. Tubes require people who have those skills.”

“But it’s a lost art,” Friedman adds. “Almost no one knows anything about tubes anymore or how to build them. All the people that did are dead now. It’s like how houses used to be hand-troweled plaster. Try and find a plasterer today who can do that work. They almost don’t exist. Stuff gets lost over time.”

“I mean, there are still a lot of tube amps that are sold. If there’s a demand, they’ll fill the void.”—Dave Friedman, Friedman Amplification

Emerging Optimism

Just when things are looking very dark, there is a faint light at the end of the tunnel. JJ Electronic is still at it and should accept new tube orders soon. Matthews’ New Sensor Corporation fully expects to make it through Russia’s current political climate. There are even rumors of Chinese powerhouse Shuguang returning.

“I think things are improving,” Monroe says, optimistically. “We’re hearing, ‘We’re getting more tubes in,’ and, ‘We’re going to be able to supply you with tubes.’ So, hopefully, for anyone that couldn’t get tubes through us, we’ll have their tubes in stock soon.”

Also, tubes never entirely went away. Look at any large retailer and you’ll find a selection of EL34s, 6L6s, 12AX7s, and more. Your choices might be limited, and the prices higher, but they’re there. Why? Because the industry saw this coming, reached out to their suppliers, and prepared accordingly.

“We started talking to the Psvane company early,” says Friedman. “We were set up with them and in a good position when this all happened.”

“Guys like Mike Matthews did tell people early on, ‘I’m getting shut down. I’m not going to be able to deliver these,’” says Monroe. “That created a bit of a panic at the time. So, we were able to order ahead and keep sales going.”

Amp Makers Adapt to Survive

Amp builders have been able to adjust to availability the same way they always have—by embracing different tubes and brands. While the name on a tube might say Sovtek, Mullard, or Mesa/Boogie, there’s a good chance it was made in the same factory. And amp builders, unbeknownst to most guitarists, often jump from one brand to another to ensure their customers get the best-sounding and most reliable tubes currently produced.

Friedman explains: “Look, tubes have to sound great, but they also have to be reliable. That’s why I've changed tube makers several times over the years—because of reliability issues. So, whatever amp brand is on a tube [in our amps], it’s just whatever tube deemed the most reliable for right now. And that’s changed a million times over the years.”

While Friedman thinks each tube has its own magic, he also believes that right now there are better ways to spend your tone-chasing money. “There’s a big variety of tubes,” he says. “They have their own gain levels and tone. They all have a sonic signature, and you need to find out what you like. But I’m of the mind, ‘Don’t swap your tubes if they’re working.’ And, if you have an amp you like, figure out what’s in it and replace them with the same tube. Just look for a well-tested tube from a reputable source. There are a lot of great tube matching/screeners out there. So, know what you’re going for and get a screened tube that has a warranty.”

“I mean, there are still a lot of tube amps that are sold. If there’s a demand, they’ll fill the void.”—Dave Friedman, Friedman Amplification

The Future of Tube Amps

Although we seem to be emerging from the tube shortage, if history does repeat itself, this won’t be the last time it happens. Also, let’s not forget the rise of digital modeling and the new generation of solid-state amps that approximate tube tone that have entered the market in recent years.

This leads to the question, “Is this the end of the electric-guitar tube amplifier?” Not according to both Friedman and Monroe. “There is enough of a market that tubes will continue. There’s still money on the table,” Friedman says matter-of-factly. “I mean, there are still a lot of tube amps that are sold. If there’s a demand, they’ll fill the void. And remember, they asked the same thing in the early ’90s. It happens over and over again.”

“Tube amps are as hot as ever,” echoes Monroe. “I’ve been in purchasing for a long time at Sweetwater, and there are just too many amps out there. Someone is going to find a way to keep them going.”

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)