Brandon Seabrook Trio: Convulsionaries by Brandon Seabrook

One of the hallmarks of guitarist Brandon Seabrook’s style is his unflinching willingness to be true to himself. If that means creating a wall of cacophonous noise while searching for a certain note, phrase, or rhythm—so be it. His music can be cavernous and unsettlingly sparse and quiet one moment and violently abrasive, noisy, and barbaric the next. It’s within that juxtaposition that Seabrook created Convulsionaries, a challenging new album with cellist Daniel Levin and bassist Henry Fraser.

After listening to the bubbling, frantic energy on “Groping at a Breakthrough” or the relentless stop-start power near the end of “Crux Accumulator,” one might wonder: “Where did this guy come from?” A native New Englander, Seabrook went to a high school with a strong music program and then ended up at the New England Conservatory of Music, where he was immersed in a petri dish of wildly adventurous academics who not only embraced the traditional language of jazz but challenged its boundaries. “That was a really encouraging atmosphere to explore your own thing,” says Seabrook. Soon after college Seabrook started to pop up on albums by avant-garde saxophonist John Zorn, bassist Ben Allison, and even a few klezmer groups.

In 2009 Seabrook, along with his brother Jared on drums and Tom Blancarte on bass, formed Seabrook Power Plant. Not only was it an apt name for the raucous punk energy the trio produced, but it conveniently alluded to an actual nuclear power plant north of Boston. This group produced a pair of albums that feature some of the most insane and absolutely shredding tenor banjo playing you could imagine. “When those two worlds came together, the guitar influenced the banjo and the banjo influenced guitar,” mentions Seabrook. “Then I was able to really start to make some music in my own voice.”

Seabrook Power Plant II by Seabrook Power Plant

It wasn’t until 2014’s Sylphid Vitalizers that Seabrook made his debut as a leader. This effort was a true solo album where Seabrook used the studio as an instrument and, along with engineer Colin Marston, created a wall of thrash banjo and electric guitar tones that somehow came off sounding like Slayer playing trad jazz. Perhaps the most impressive part of the project was that it was all played in real time to a click. Seabrook took a step away from the tenor banjo with a pair of albums released in 2017. Needle Driver, with drummer Allison Miller and bassist Johnny Deblase, featured a more traditional instrumentation, but the wacky, glitchy riffs and rhythms were anything but. Die Trommel Fatale is Seabrook at his most expansive and experimental with a dual-drum sextet that is as powerful and unrelenting as anything in his catalog.

Die Trommel Fatale by Brandon Seabrook

Considering how Seabrook progressed from noise-rock jazzer to the commander of his own dual-drum monolith, Convulsionaries, makes sense. Its sympathetic compositions give each member their own little corner of sonic space and creates more room for melodies, counterpoint, and at times, pure minimalism. We caught up with Seabrook to discuss his somewhat dashed hopes of becoming a more traditional jazz guitarist, developing a unique voice, and his mongrel Tele that doesn’t play well with most amps.

It seems like every time a new project comes along, you start with a totally blank slate. How did this particular trio come together?

When the group started, it had a drummer. There was a gig booked and the drummer couldn’t make it, but I said let’s do the gig anyway. After, you know, the first 30 seconds, I was like, “Wow. This is something really special and unique.” I was hearing all these other textures coming through, something you would lose if you had drums eating up some of that range. Plus, Henry and Dan have incredible energy, their rhythmic sense is really strong, and their attack is really percussive. They really ransack their instruments for all their percussive qualities and really get in there. So much more timbre can come through without the drums. At that moment, I said I wanted to make each project a little bit different and to have its own character. The record I put out before this [Die Trommel Fatale] had two drummers, so I wanted to get it down to this semi-acoustic thing. It just made sense. I didn’t set out to do that, but I just felt I had to. With drums, it would still be cool, but it would lose some of its uniqueness.

Even the most sensitive of drummers would add a layer of heaviness.

There are so many great drummers. The last album, where I had two drummers, I had it so there were no cymbals involved, just hi-hats. No crash or ride cymbals. I always try to give the drums a little bit of direction. I guess I’m hardest on drummers in terms of their role. Not hard, but I give them the most direction or parameters. I don’t know, I feel like I’m just so picky about how the drums fit in.

Do you play drums?

No. My brother is a drummer. I can’t. I just like less cymbals, although there are many great cymbalists here in New York that I play with. There’s a palmful. If I play with Matt Wilson, I’d be like, “Yeah, cool. You can play the cymbals.”

There’s such a range of sounds on “Vulgar Mortals.” It almost seems like sections of the song are entirely different tunes.

The dichotomy of that song might not come through as much if we had drums. I’ve tried to think about form a lot and think about it not so much as going back to the beginning but expanding it. A lot of the stuff in the second part of “Vulgar” are motifs from the first part, but heavily developed. It’s no problem keeping time without the drums, plus time for us is pretty elastic. People have the freedom to go away from it if they want, but it’s pretty organized.

At what point in your musical upbringing did you head toward avant-garde improvisatory music?

I guess it kinda started before NEC [New England Conservatory], probably in high school when I was listening to a blender of so many things going on. There was a lot of jazz like Eric Dolphy and Cecil Taylor, but also a lot of punk rock. I also listened to tons of blues-based jazz and post-bop jazz. Jimmy Smith was a huge influence because the blues is such an easy way to get into jazz. So, I listened to tons of that stuff while this other experimental thing was happening. All the influences were there, but I wasn’t really playing that kind of stuff in high school. It seemed so far away to actually be able to do it, but I was consuming it. I didn’t really have the facility yet to be confident enough to go that free-form. It didn’t come until later when I started to play with my own bands in college and just throwing myself into it.

After hearing your records, it can be easy to miss the confluence of the aggressive, visceral side and the more academic stuff. At NEC, how did you balance that?

It was tough. It was in its embryonic stage, since I was still dealing with technical stuff on the guitar. I was still wrestling with the insecurities you have in college and just trying to get the stuff out. It was like going back to the punk rock thing where you were composing off the page and it was motif based and just trying to harness the energy of that along with some advanced harmony and longer forms.

Did you ever go through a period where you aspired to be a more traditional jazz guitarist?

Oh yeah! Sure. At the end of high school and during my early years at NEC I was trying to do that. It wasn’t until I got with Bob Moses, the drummer, and his whole approach to the clave. He would put a clave into every jazz tune. He would say, “Here are the hits in ‘All the Things You Are’” and then he would grab my guitar and show me some amazing rhythmic ideas. That’s when the stuff started to break apart and I began to construct things more rhythmically. I could have a rhythmic construct and a rhythmic form rather than harmonic. He also talked about melody a lot and klezmer music, where you ornament the melody and there’s not a lot of improvisation. In jazz school it’s a lot about just getting to the solo and finding your way through the changes and the rhythm thing isn’t always the most important. With the focus on all the possibilities of rhythm he started to push me in a direction away from jazz harmony. Jazz is all about rhythm, but at that point in school I was focused on something different than what I was being taught. When I met Bob it just gave me a new approach and helped move things in the direction they are. Plus, a few tunes on this new album are rhythmically constructed.

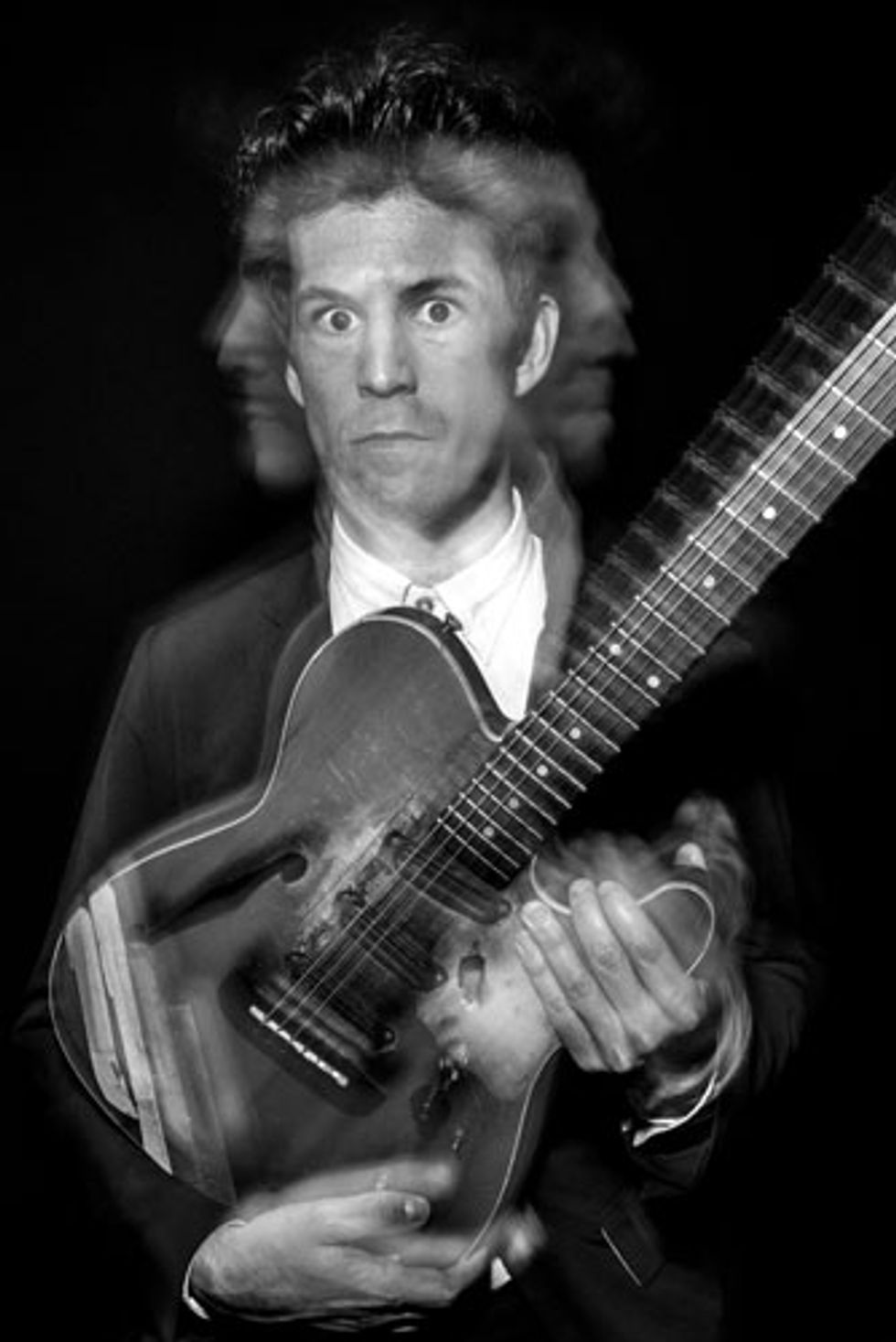

Things can get a little blurry when listening to Convulsionaries, the latest trio album by Brandon Seabrook.

Photo by Reuben Radding

With a tune like “Qorikancha,” where’s the line between composition and improvisation?

The intro to that piece, like the first 20 seconds, is very composed and then the melody comes, and we play it through a few times and then I give people space to expand on it and do their own thing with it—which is often better than what I wrote. That’s why I have them in the band. I know Daniel will come up with something probably better than what I could write. There’s a lot of stating the melody and then turning it over to the band. I like the juxtaposition of that and then parts that you can’t play anything else but what’s written. That song is a good example, because the intro is like, you just can’t play anything else and then we state the melody a few times and then slowly break off of it. We can’t let the energy of the free-form improv affect the next part. We then come back and focus to make that part sound romantic, or quieter, or whatever.

In some more avant-garde, experimental groups it’s more about getting into the free-form freakout. That can be really hard to reign in and be able to give the listener something to hold on to.

Yeah, sure. One of the things I wanted to do with this record was to stay in zones for a little longer. A lot of my stuff is very schizophrenic with a lot of jump cuts, but with this group I wanted to anchor stuff a little longer. I don’t know if you can tell, but things stay in a space a little longer to develop and that gives the musicians some more freedom to develop ideas. Other bands that I have, it’s more of a shorter space, but with this group I could’ve let it sit even more. With our live shows I’m trying to make it like that.

As a composer, how do you view the relationship between the guitar and cello?

They both have a really wide range and go from the bottom to the top really quickly. Both are visceral and can really get some attack, and also sound sweet and melliferous. Our range is large, and I know Dan has that range, so we can change really quickly between something beautiful and harsh. The timbre of the cello and guitar almost has this electric sound to it, this scratchy sound that really works. There are a couple of moments where I put on some light distortion and the cello is with me and it just blends.

How does your composing process change when you’re generating material for so many groups?

I write for the group. At first, we had a drummer, so I wrote for that. I tried to expand my palette and get to know what the cello is and how we can use each individual. The guys in this band are strong individual players and I knew what each could do so I wanted to give them space to do it and write material that was easily expanded on and I knew they would just devour. Plus, I just wanted to write some music with new textures with the strings.

Brandon Seabrook’s Gear

Guitar

Late ’90s Heavy Metal Telecaster with Strat neck and DiMarzio pickups

Amps and Cabs

Vintage Magnatone Hi-Fidelity

Modded Fender Twin Reverb

Peavey Bandit 65

Chunky Homestyle Cabinet

Effects

Blackstone Appliances Mosfet Overdrive

Arion SAD-1 Stereo Delay

Fairfield Circuitry Barbershop Overdrive

I see you playing this well-used Tele. Can you tell me about it?

The guitar is a Fender from the early ’90s and the model name was something like Heavy Metal Tele. You can find them online, and they also made a bass that went with it. That’s my only guitar right now. I bought it at NEC from a friend for like $300 and his dad had used it as an electronics project and put all these other pickups in it. That’s really been my main guitar for the last 22 years. I’ve beat it to death, we’ve just been through so much.

That’s not a Tele neck, right?

It’s a Strat. You know, I didn’t even know that until like two years ago. [Laughs.] Strat neck, Tele body. It has DiMarzio pickups. It has a really hot DiMarzio in the bridge and two other warmer pickups. It’s just my guitar. We’ve hated each other, we’ve loved each other. The neck is always moving. It doesn’t sound good through a lot of amps. With some of the sideman gigs I get, I really need to get a guitar that stays in tune, sounds a little more, not generic, but maybe warm to the ears. Although, this guitar is really versatile. If I have the right amp, I can really make it sound like a lot of different things.

You’re also an accomplished banjoist. How did that start?

In college I started on the tenor banjo. It’s tuned in fifths [C–G–D–A]. I don’t do any bluegrass, but sometimes I have to fake it for people. I have a 5-string banjo and I know how to play it a little bit, but I never take it out of the house. When the banjo and guitar were separate, I was just banging on the banjo. I took some lessons, so I could learn how to read on it and play other people’s music. The banjo playing started to influence my guitar playing and I just felt more comfortable when all the worlds came together.

What were you listening to that made you want to pick up a tenor banjo?

I heard Eddie Peabody and the Louis Armstrong Hot Five, but it wasn’t until I was in college and played klezmer and Eastern European folk music. I had a teacher that told me when this music came to the United States, they used the tenor banjo. My teacher said the music library has a tenor banjo and I should check it out. It took me a few years to really learn it. That started to influence my guitar playing and then I started to do gigs on both.

Since you’re getting ready to head out on the road, what gear are you planning on bringing along?

I’m taking a Chunky Homestyle cabinet. This guy, George Draguns, makes them in Philly. They are these beautiful wooden cabinets. I’m also taking a Peavey Bandit 65 head, solid state, through that cab. Solid-state amps and my guitar really get along well.

Why do you think that is?

I like to have a super crystalline clean sound and then have a sort of overdriven sound, and then a really overdriven sound. I’ve found with my guitar with tube amplifiers, like especially Fender Twins, I can’t get it really, really clean. I’m really all about blending. I think it’s a reason I get called for a lot of things because I can really blend with people and a lot of times, I’m the only electric instrument.

Is your live rig different from what you used on Convulsionaries?

On the recording, I used my vintage Magnatone Hi-Fidelity, which I love. My guitar and Fenders just don’t get along that well. The other amp was an early ’70s Fender Twin, but my friend had it souped up and I used it for some reverb passages and the really, really bright stuff. I think I had the treble all the way up and the bass down. The Twin wasn’t too modded, it had a new speaker and had been fixed up, but it was a good old Twin. I usually hate Twins, but I wanted to exploit all the harsh qualities of this Twin and my guitar. Sometimes I mixed both amps. I think it’s effective. It was like, “Okay, I hate you but we’re going to make it work.” But the Magnatone has a lot of nice midrange and the tremolo is real pitch shifting and the reverb is incredible. It’s just too delicate to take on the road. On the tune, “Mega Faunatic” all the rich reverb and tremolo is coming from the Magnatone. You can just tell because it sounds like water. Maybe that’s the only tune I used that on because my footswitch wasn’t working. On “Bovicidal,” you’ll hear some Twin tremolo-ing in the middle section.

I know you don’t use many pedals, but did any appear on this album?

Yeah! I use a Blackstone Appliances overdrive, which is really nice. And I use an old, early ’80s Japanese analog delay called the Arion SAD-1. It’s just a great pedal. I’ve been using it for years and years. About every four years I need to buy a new one. The decay sounds great and it’s just a piece of plastic that’s easy to move around. Those are the main pedals I use live. Sometimes I’ll use two Arion delays, but only one on this tour because it’s more about culling out what you can get out of the guitar itself.

I have to say; the most underrated part of your discography is how creative you are with song and album titles.

I’m glad you think that! My wife gives me feedback on them. She’s into it. Sometimes I feel like it’s too goofy.

YouTube It

On a recent gig in St. Louis, Seabrook takes it way out on his heavily modded Heavy Metal Telecaster that he bought in college for $300.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)