New York, New York (January 31, 2019) -- Christie’s is honoured to bring to auction highlights from the personal guitar collection of rock’n’roll legend, David Gilmour, guitarist, singer and songwriter of Pink Floyd, on 20 June 2019 in New York.

Comprising more than 120 guitars, Gilmour's collection focuses on a selection of his preferred Fender models including Broadcasters, Esquires, Telecasters and Stratocasters, led by a guitar as iconic and recognizable as the historic performances for which it was used - the 1969 Black Stratocaster (estimate: $100,000-150,000). Detailing the musical history of one of the world's most influential guitarists, the sale will be the largest and most comprehensive collection of guitars to be offered at auction.

All sale proceeds will benefit charitable causes. Estimates range from $300 to $150,000, appealing to a wide spectrum of guitar aficionados, fans and collectors alike.

A global tour of the collection will launch in London at Christie’s King Street from March 27-31, 2019 where the full collection will be on display, followed by highlights in Los Angeles May 7-11, and then the New York sale preview ahead of the auction from June 14-19. During the exhibitions, the sound experience will be provided by Sennheiser.

Quote from David Gilmour: “These guitars have been very good to me and many of them have gifted me pieces of music over the years. They have paid for themselves many times over, but it’s now time that they moved on. Guitars were made to be played and it is my wish that wherever they end up, they continue to give their owners the gift of music. By auctioning these guitars I hope that I can give some help where it is really needed and through my charitable foundation do some good in this world. It will be a wrench to see them go and perhaps one day I’ll have to track one or two of them down and buy them back!”

Kerry Keane, Christie’s Musical Instruments Specialist: “For the last half century David Gilmour’s guitar work has become part of the sound track in our collected popular culture. His solos, both lyrical and layered with colour, are immediately identifiable to critics and pop music fans as readily as the brushstrokes of Monet’s water lilies are to art historians. These instruments are unique in that they are the physical embodiment of David Gilmour’s signature sound throughout his over 50-year career. Like palette and brush, they are the tools of the trade for an iconic rock guitarist.”

Collection Highlights:

Leading the Collection is David Gilmour’s 1969 Black Fender Stratocaster, purchased in 1970 at Manny’s on West 48th Street in New York (estimate: $100,000-150,000). ‘The Black Strat’ quickly became his primary performance and recording instrument for the next fifteen years and it was extensively modified to accommodate Gilmour’s evolving style and performance requirements.

The Black Strat was played on "Money," "Shine On You Crazy Diamond" and the legendary solo on "Comfortably Numb." It was key to the development of the Pink Floyd sound and was instrumental in the recording of landmark albums such as Wish You Were Here (1975), Animals (1977) and The Wall (1979), and of course Pink Floyd's seminal 1973 masterpiece The Dark Side of the Moon, widely regarded as one of the greatest albums of all time.

The guitar can also be heard on Gilmour's critically acclaimed solo albums including David Gilmour (1978), About Face (1984), On An Island (2006) and Rattle that Lock (2015). After a period of temporary retirement while on semi-permanent loan to the Hard Rock Cafe, Gilmour reclaimed The Black Strat for Pink Floyd's historic reunion concert at Live 8 in London's Hyde Park on 2nd July 2005, reinstating it as his guitar of choice for the next decade and firmly establishing its place in rock’n’roll history.

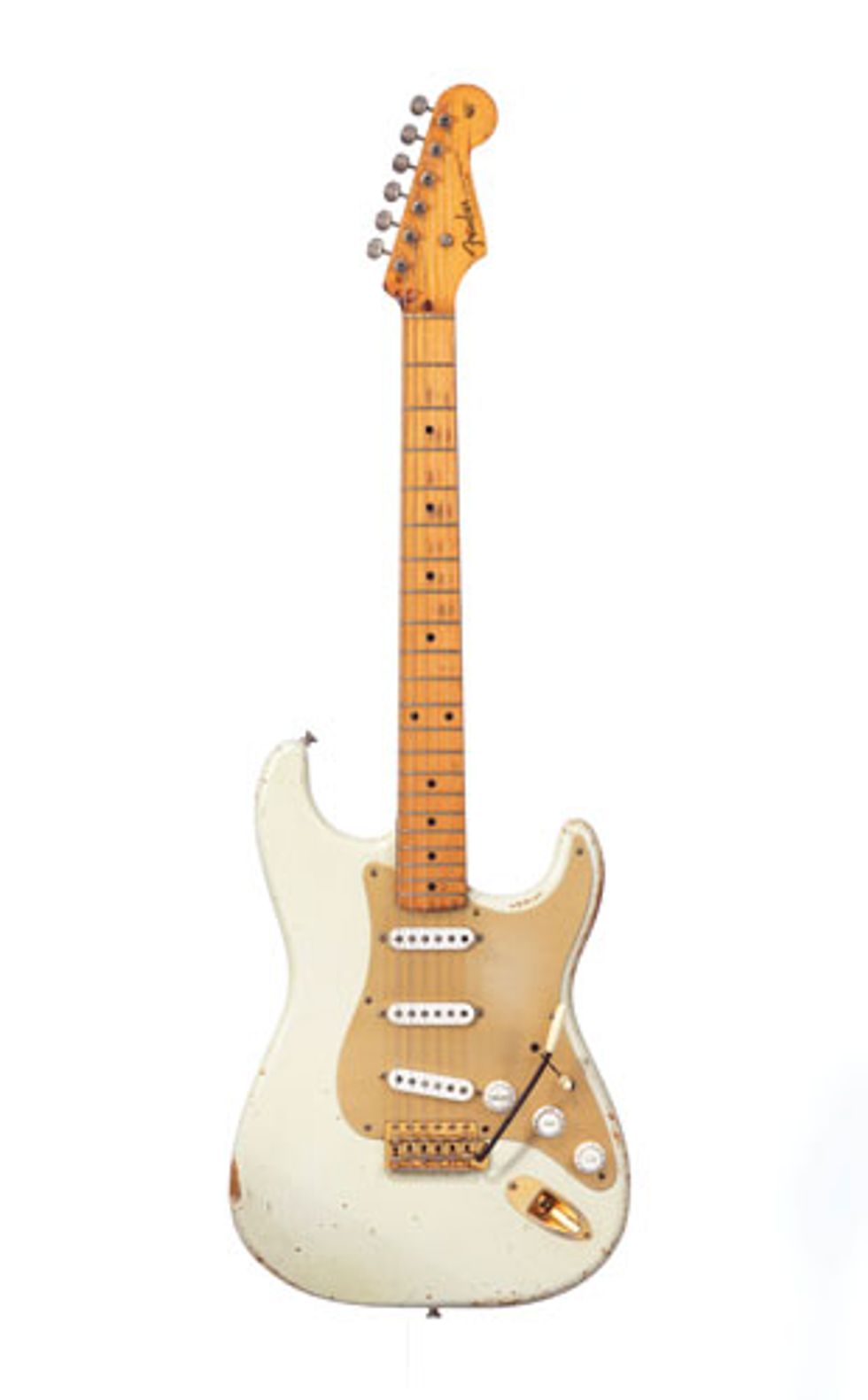

Another important guitar offered is Gilmour’s 1954 White Fender Stratocaster #0001, which has become one of the instruments synonymous with his long artistic career (estimate: $100,000-150,000). Gilmour acquired ‘The #0001 Stratocaster’ in 1978. Its use on several recordings, such as Another Brick In The Wall (Parts Two and Three), and on the concert stage, make it readily recognizable by both fans and connoisseurs.

Additional collection highlights include a 1955 Gibson Les Paul, famous for Gilmour’s guitar solo on Pink Floyd’s 1979 number one single Another Brick in the Wall (Part Two) (estimate: $30,000-50,000); and an incredibly rare Gretsch White Penguin 6134 purchased for his private collection (estimate: $100,000-150,000).

Further Fender highlights include the 1957 ‘Ex-Homer Haynes’ Stratocaster, with gold plated hardware and finished in the rare custom color of Lake Placid Blue (estimate: $60,000-90,000); a Candy Apple Red 1984 Stratocaster 57V (estimate: $15,000-25,000), which became his primary electric guitar during the 1980’s and 1990’s, used during recording and touring of the Pink Floyd albums A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987) and The Division Bell (1994): and an exceptionally early 1954 Stratocaster, (estimate: $50,000-70,000), believed to be one of a group of Stratocasters produced by Fender prior to its commercial production release in October 1954.

Echoing Gilmour’s early musical influences of the Everly Brothers and Bob Dylan, the collection offers several acoustic guitars. Examples include a 1969 D-35 Martin purchased on the streets of New York in 1971, and used as both Pink Floyd and David Gilmour's main studio acoustic, notably on Wish You Were Here (estimate $10,000-20,000); a Gibson J-200 Celebrity (1985) acquired from John Illsley of Dire Straits (estimate $3,500-5,500) and a unique Tony Zemaitis (1978) custom acoustic bass guitar (estimate $15,000-25,000).

For more information:

Christies

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.