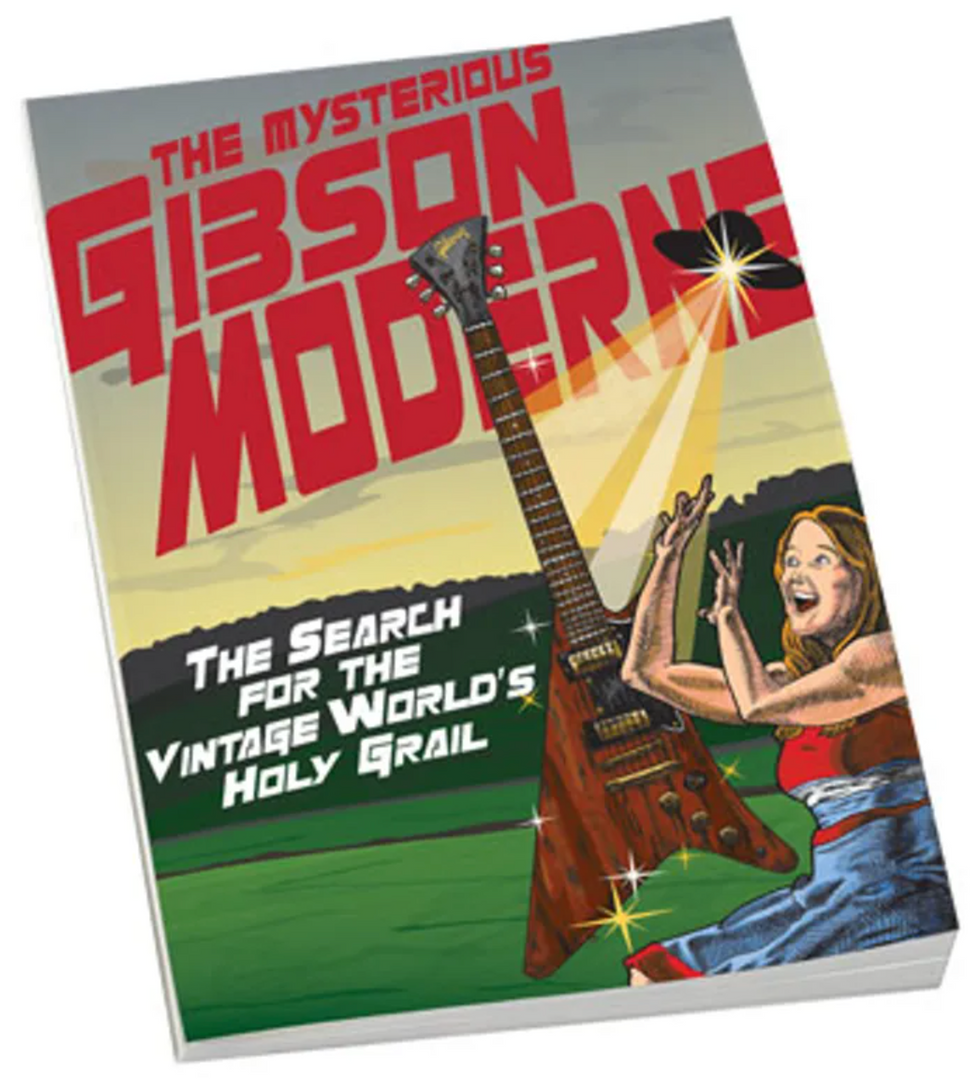

In the vintage guitar world, the Gibson Moderne is the ultimate maddening mystery: the Holy Grail, El Dorado, the Unicorn, UFOs and Big Foot, if you will. It was designed along with the Flying V and Explorer as part of Gibson’s “Modernistic” series in 1957 (the era of pulp fiction and the space craze), in order to shake up Gibson’s stodgy image. The V and Explorer made it into production, but the Moderne seemingly never saw the light of day, until Gibson saw fit to finally issue a limited run in 1982. To this day, not a single Moderne has ever been verified as original by anyone, although there have been forgeries, copies, and more false sightings than one could imagine. This article is a condensed history of the guitar, the fifty-plus-year search for an original example—the myth, the mystery, the facts and the rumors.

A Controversy is Born

Ted McCarty, Gibson’s president during their golden age of the late 1950s, commissioned three “modernistic” guitars in response to disparaging comments that had gotten back to him from the Fender camp in California. McCarty realized Gibson’s solidbody guitar line was rather staid, so he decided to shake the industry up with wild guitars inspired by futuristic, space-age concepts. After settling on three designs from the one hundred or so that were submitted, prototypes were made to be shown at the 1957 NAMM (National Association of Music Merchants) show in Chicago. There’s speculation that only the Flying V and Explorer, then called the Futura, made it to the show, and that the Moderne was scrapped.

Others say all three guitars were shown, and that while the Flying V and Explorer achieved their goal of “shaking things up” at the show and getting into limited production, the Moderne was so poorly received that all the prototypes may have been scrapped at the Gibson factory—but not before one was supposedly sent out to Gibson’s case supplier for fitting. Ted McCarty went to his grave claiming that at least several Modernes were built, but he didn’t know what had happened to them. Some Gibson employees say none were produced. A few say the prototypes were cut up and destroyed. A few others maintain that two Gibson employees took the parts and assembled three Modernes outside the factory, yet nobody seems to remember either of these men. Almost all the original players in this fascinating mystery tale are deceased.

If you’ve never seen the Moderne, it’s an extremely unique design that’s impossible to ignore. The left side of the body resembles a Flying V or a shark fin, while the smaller right side looks like an old-style can opener or a fish hook. It’s a radical shape even today, so one can only imagine how it must have appeared in the conservative Eisenhower era fifty-two years ago. The headstock was shaped like a widened boat paddle, with four string guides. Some think the Moderne is butt-ugly; others consider it a thing of beauty. You can make your own judgment.

Sightings: Fakes and Forgeries?

Illustrations: Michael C. Ludwig

Enter Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top, who owns what he believes and claims to be an original Moderne, purchased for “a little bit of nothing” in 1971. Although this guitar has been photographed, Gibbons, who has been described to me by someone who knows him well as a master of “smoke and mirrors,” has never allowed a single vintage guitar expert to examine his instrument, not even his friend George Gruhn. He has steadfastly refused to make the guitar public to any extent other than two questionable photos. Examining these images, it appears that Billy G’s Moderne looks very similar to the Japanese Ibanez “Futura” Moderne copy that surfaced in 1975. Moderne copies have also been made with the names Greco and Antoria on the headstock, and Gibson produced offshore Moderne copies in the year 2000 with the Epiphone name.

Speaking of replicas, luthier Glen Miller (no relation to the late swing bandleader) manufactures Moderne, Explorer, and Flying V replicas at Wrona’s House of Violins in Lewiston, NY. Miller began performing repairs shortly after getting his first guitar in 1970, and learned his trade in the shop of the late vintage guitar dealer Dan Hairfield. In 2003, Miller found a source for original Gibson parts.

“I had been searching for a Moderne and came across a listing for some supposed original Moderne parts,” he says. “I contacted the seller, who had been a Gibson subcontractor and was fortunate enough to have attended the auction [when they closed up] the Kalamazoo factory in 1984. He purchased many bodies, necks and other hardware, but then put the parts in his storage area and forgot about them. I made a deal for most of the stuff he had, including original ‘82 Moderne bodies and necks, plus ten Gibson logos.”

Miller has built three Modernes from Gibson parts, plus five from his own parts, in addition to four Explorers and two Flying Vs.

The Plot Thickens

Unlike some, Glen Miller believes the original Moderne never existed.

“I don’t think one was ever made in the ‘50s,” he comments. “It is clear from photos that Gibson rushed some prototype Vs and Explorers so they could display them at the ’57 NAMM show. The Moderne never made it into a single picture taken at the show. All the supposed sightings sound just like people who claim to have seen a UFO. The prototype Vs, Futuras, and Explorers with the Futura headstocks have all shown up. If there were any real ‘50s Modernes, at least one would have surfaced by now. A ‘50s Moderne does not exist.”

Luthier Dan Erlewine claims to have owned a re-necked Moderne, but no longer has the guitar and never photographed it when it was in his possession. According to Erlewine, “A guy brought it into my shop on the outskirts of Ann Arbor and wanted to sell it. He said his dad sent it to Kalamazoo to have a Melody Maker neck put on it, because he liked the feel of his buddy’s Melody Maker and wanted his guitar to have the same. I thought it was an Explorer, which I’d never seen, and I had never heard of the Moderne or the Futura. I paid $175, which was a lot of money at the time.”

“When I removed the pickguard,” he continues, “I found some routing had been done, and I believe different pickups had been installed—maybe someone started a third pickup and never finished. I filled the unwanted rout with plaster of Paris, of all things, and painted black over the hole. I sold the guitar immediately to Ann Arbor Music to get my money back. They sold it to Doug Green, who worked for George Gruhn. I think the parties got into some pretty good arguments over it.” That guitar was supposedly sold to a Japanese businessman. George Gruhn claimed to have examined it and deemed it a fake.

“George knows more than I do about vintage guitars,” Erlewine states. “I’d say he didn’t see it. He bought it through his employee, Ranger Doug.”

Dan Erlewine has never seen Billy Gibbons’ Moderne, either: “Only recently did I see a glimpse of it in the photo of Billy in the convertible filled with guitars in the Ron Wood book. How would I know if it’s original? What does ‘original’ mean anymore, especially with a guitar that has never been proven to exist.”

“I have no idea why Billy has been so secretive about it,” he adds. “I’ve never met Billy. He’s a big star with lots of valuable guitars, and if it were me, I’d be protective about them, too. He hasn’t shown it to anyone because he doesn’t feel like it; he doesn’t have a need to. I don’t think Billy claims to be an expert on vintage guitars. He’s an expert at playing them!”

Erlewine doesn’t subscribe to the theory that an original Moderne would have surfaced by now: “If there were only three allegedly made, it’s possible the owner doesn’t even care about guitars, or have a clue what it is. It’s a big world, and lots of strange things happen all the time.”

“I never thought about the Moderne myth very much. The most I thought about it was a couple of years ago, when a man flew to Athens, OH, to show us a ‘real’ one that he had come across—he was writing a book about it and wanted verification. He and the guitar’s owner paid to have experts Phil Jones, Tom Murphy and Michael Stevens flown in for the weekend as part of the inspection team. Michael was ill and couldn’t attend, but Phil and Tom came. We had seen at least fifty photos of it before the get-together took place, and they were good enough to warrant us looking at it. Once the case was opened however, we could tell it wasn’t real. Probably some of the color photos in Ron Wood’s book are of that guitar.”

Summing it up, does Dan Erlewine think the Moderne ever existed? “I have no idea,” he answers, “but I’m starting to doubt it.”

One Man’s Quest for the Truth

As previously mentioned, Gibson relented to requests and officially introduced the Moderne in 1982. Howard Leese, formerly of Heart, was given the first prototype, which was painted Candy Apple Red. He also purchased one for his guitar tech. Both later sold the guitars for a tidy profit. Only 183 Modernes were produced in this run, and the public reaction was generally negative. Other than the Korean-made Epiphone copies, Gibson has refused to manufacture the Moderne since.

This brings us to Ronald Lynn Wood, a guitarist originally from Flint, MI, and now of Gainesville, FL, who became fascinated by the Moderne as a young man and set out to unravel the mystery of this elusive guitar. His new book, Moderne: The Holy Grail of Vintage Guitars, has just been released by Centerstream Publishing, and it is the most exhaustive and comprehensive accounting to date of the search, the history, and the rumors and facts surrounding the Moderne. Wood saw what he believes was a Moderne hanging in a Flint pawnshop in 1978, and from there began his quest for the truth behind the mystery.

“It was like no other guitar I had ever seen,” he recalls. “I distinctly remember the lower horn was shorter than the top. I never did get that Moderne, but always wondered if it was real or not. When I was thirteen, I used to subscribe to the newsletter put out by Guitar Trader from Red Bank, NJ. From my earliest days as a musician, I was fascinated with vintage guitars. There was all this talk about the Moderne in various books and magazines, but very little substance. Did they make one? Where was it?”

Wood goes on to say, “I met Cohn Rude through an article he had written [on the Moderne] in Vintage Guitar magazine. He was very helpful and shared a lot of information with me, as did a good friend of his, Wayne Johnson. I had been collecting information about the Moderne for a long time, but after talking with them, it gave me the fire to finish the book.”

Wood started saving information on the Moderne twelve years ago, and it took him five years to complete the book. He claims to have a great deal more information that didn’t make it into the book, information that he could not substantiate.

“A few days ago,” Wood relates, “someone sent me a photo of a [Gibson] factory worker with a Moderne on her work bench in the final stages of assembly, so I absolutely think the guitar existed. I think at the very least two prototypes were made, but most likely four. Ted McCarty, John Huis and Julius Bellson, all Gibson management at the time, said there were several made. I spoke to an ex-Gibson employee, who refused to be identified, who claimed to have seen Modernes at the factory in 1963. Ren Wall of Heritage Guitars claims to have played a Moderne in the Gibson morgue in Kalamazoo in 1963, and borrowed it for use in a school dramatic production. Even some former Fender reps I spoke to said they saw all three futuristic guitars at the 1957 NAMM show.”

“I would really love to see Billy Gibbons’ Moderne in person. He is strangely secretive about that guitar, which makes me wonder. He did an article in Guitar World magazine in 1982 and they photographed it. The rarest guitar in the world, and all you see is a sideways photo in the front seat of a car? He didn’t even include it in his own book! My guess is that his guitar might have vintage-correct parts, but that doesn’t make it real. Not even the most ‘guru’ of vintage guitar experts has ever had the opportunity to inspect it. Billy gets any guitar custom made for him—why not a vintage-correct Moderne?”

Wood believes a genuine Moderne would have surfaced by now, but there’s always the possibility it hasn’t: “I used to think one would have appeared by now, but I started talking to some fellows on the mylespaul.com forum a while back, and one of them told me his grandma had some ‘old guitars that say Gibson on them’ up in her attic. She had no idea what they were, but they were old, perhaps from the ‘50s. It’s highly possible that someone has a Moderne and might not have a clue as to its worth. I remember a couple years ago, some guy bought a ’79 Flying V from Goodwill for $25!”

Wood says he would like to see Gibson reissue the Moderne again: “I’ve sent many letters to them asking for another reissue. I doubt they will make it again. The guitar was ridiculed in 1957, and only sold 183 or so in the early ‘80s. One guy I interviewed for the book said he was a member of the Gibson Custom Club, meaning that if you have enough money, they’ll pretty much make you anything you want, as long as it was based on a legitimate Gibson model. He asked for a Moderne and they couldn’t make him one.”

Can We Get Some Forensics on this Thing?

Deciding to go to the experts, I contacted George Gruhn of Gruhn Guitars, Stan Jay of Mandolin Brothers, and Buzzy Levine of Lark Street Music.

George Gruhn commented, “I have never encountered any original Moderne guitar made prior to their so-called reissue in the early 1980s, nor have I ever had a conversation with anyone who claimed [to me] to have seen one. I have significant doubts that they were ever made.”

Stan Jay said, “The common wisdom is that Gibson had a patent on the Moderne. I see it as a fantasy-based instrument from the 1950s space age. It just didn’t take off. The Moderne is like the Sasquatch of the vintage guitar industry, or those fuzzy pictures you see of UFOs. You can’t really tell what they are. I think it’s a wonderful thing to have some mystery. Every industry needs a mystery, and the Moderne is our mystery, our Sasquatch. The real story of the Moderne is the myth itself.”

Buzzy Levine remarked, “The only myth I know is that Billy Gibbons supposedly has one, but why hasn’t he shown it to anyone? Who wouldn’t want to make it public that he owned the rarest electric guitar ever made? If there were Modernes out there, they should have surfaced by now. I suppose there could have been one or two made.”

I Want to Believe

As someone who has done his own Moderne research and generally enjoys the “thrill of the hunt,” I would be remiss in not expressing my own opinion. I believe Billy Gibbons’ guitar is a copy, an Asian lookalike—maybe a prototype that got into this country, a custom guitar he had built, or perhaps a mongrel that contains some original Gibson parts. The headstock is the standard Les Paul or SG-style “open book,” not the “paddlestock” of the original design. It would not be unlike Gibbons, a secretive man, to keep the guitar a mystery to perpetuate the myth, mystery and mojo of the Moderne.

Although I would like to believe there’s an original Moderne under a farmer’s bed somewhere in rural USA, I honestly think one would have surfaced by now, given the vast common knowledge about rare guitars that exists today. Even pawnshop owners regularly refer to vintage guitar price guides, and I personally know several antique dealers in my area who are savvy about old guitars.

A verified, original Moderne would easily fetch seven figures. If I found one, it would most certainly go up on the block for sale. Finally, while I believe the Moderne did exist in prototype form, it seems most likely that all original examples were destroyed in the Gibson morgue by the early ‘60s. At best, some of the parts may have been stolen out of the factory and reassembled into quasi-Modernes.

The bottom line: an original Moderne exists only in the minds of those who believe the myth, but admittedly, it’s fun to believe otherwise and continue the hunt for the vintage guitar world’s Holy Grail.

For information on Glen Miller’s Moderne, Explorer and Flying V replicas, visit: wronashouseofviolins.com.

For additional information on Ron Wood’s book, Moderne: The Holy Grail of Vintage Guitars, go to: centerstream-usa.com.

[Updated 2/24/22]

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)