Inside each box containing a brand new PRS pedal, there’s a little fold-out card with a picture of Paul Reed Smith and a simple caption: “I hate pedals.” It’s not hard to imagine Smith’s indifference to stompboxes. PRS guitars are immaculately executed, ultra-playable instruments that reflect a focus on elemental interactions between fingers, strings, and fretboard. Indeed, for much of Paul Reed Smith’s career, stompboxes were probably held in the same regard as a broken toaster—a needless impediment to the communication of unadulterated tone.

Certainly, there is a visceral thrill to playing a guitar without effects—particularly one as nice as the average PRS. But while that’s true, stompboxes are, to many musicians, equally artful and thrilling vehicles of expression. And more than a few pedals have done their magic with a PRS guitar at the other end of a cable.

PRS’ three debut pedals—an optical compressor, overdrive, and dual flanger—do not feel like willy-nilly concessions to market pressures. In fact, in keeping with PRS tradition and ethos, these pedals seem selected and designed to offer minimal intrusion on the guitar/amp relationship if the player chooses that route. But they also have the bandwidth to be bold and even positively extroverted. Unsurprisingly, they are also built to a very high standard of quality and reflect an intense attention to detail.

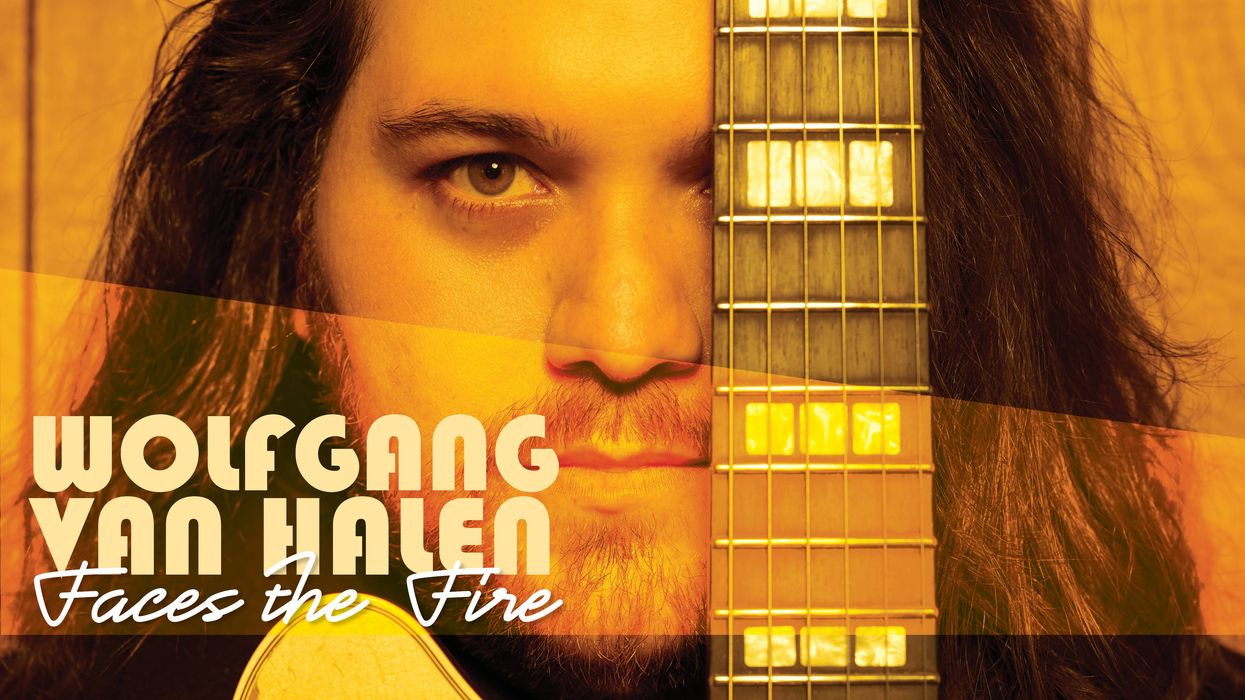

PRS Horsemeat, Mary Cries & Wind Through the Trees Demos | First Look

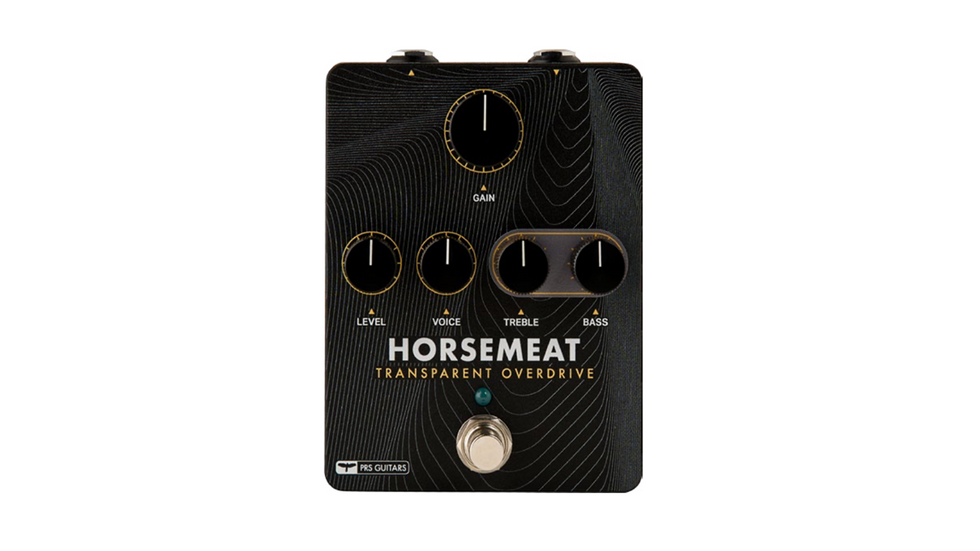

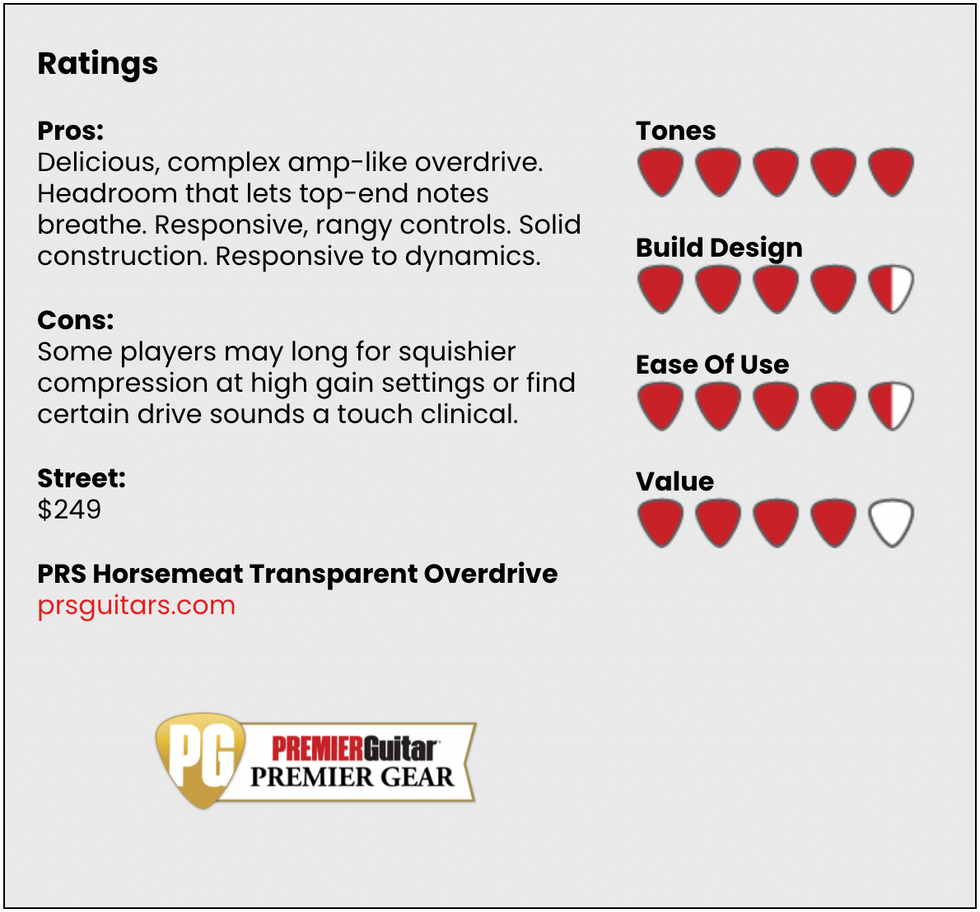

Horsemeat Transparent Overdrive

Horsemeat isn’t a pretty name, but I’m guessing it alludes to making short work—mincemeat, if you will—of the Klon Centaur in a head-to-head battle. It’s hard to know exactly how much inspiration PRS derived from the Klon. PRS emphatically insists that Horsemeat is a very original design. And its circuit board is flipped, making it impossible to determine similarities in topology. It shares at least one important design element with the Klon, in the form of germanium clipping diodes. In a very general sense, germanium diodes tend to contribute soft-edged compression and a high capacity for distortion. But without knowing how other components in the circuit modify the performance of the diodes, you have to rely on your ears. And alongside my favorite Klon clone, Horsemeat sounds like a very different animal indeed.

Next to the Klon clone—which serves here as a familiar baseline rather than a direct comparison—the Horsemeat’s headroom and the leeway to work with it via picking dynamics or the flexible and practical control array is striking.

Though the Horsemeat can get aggressive, moving through the gain control’s range yields many nuanced shades. At maximum gain levels (and with relatively neutral treble, bass, and voice settings), the Horsemeat exhibits a lot of Marshall-plexi-like characteristics. There’s a distinct sense of size, a viscerally satisfying growl to the voice, and lots of top-end response that gives first- and second-string output heat and room to breathe. If you keep the output level at a reasonable setting, the compression in the distortion never feels oppressive or muddy. Instead, the pedal’s natural compression tends to lend cohesion. And even at advanced output level settings (and there is a lot of room to run in that respect), the distortion remains articulate.

“Moving through the gain control’s range really yielded shades of gain rather than heaps of extra crunch and aggression.”

Reducing gain reveals an impressive capacity for touch sensitivity. I can’t remember the last gain device I used that responded so well to variations in fingerpicking intensity. Guitar volume attenuation, too, yields rich and very pretty clean tones. And if you’re frustrated by your single-coil pickup’s tendency to bleed high end with volume reduction, you’ll be tickled by how readily the Horsemeat can replace some of that sparkle.

The bass and treble controls not only have a lot of range, but offer very colorful and varied tones within those areas. You can extract exceptionally bright tones out of the Horsemeat (in fact, extra-trebly settings rather than high-gain sounds struck me as the pedal’s most “extreme” settings). The voice control, which shapes frequency response in the clipping stage, helps you color the pedal’s tones in even more specific ways. Aggressively clockwise settings sound and feel hot and explosive, while the lower-to-middle third of its range have a sweetness that works with the pedal’s intrinsic dynamism to add soulful movement to chord melodies.

The Verdict

It’s hard to imagine an overdrive user that wouldn’t dig working with the Horsemeat. Players that prefer the squish in overdriven Fender tweed circuits might find the output a touch too even across frequencies. But I suspect a lot of players that love the more articulate side of a Marshall’s voice or really obsess over relative transparency will find a soulmate in this fine and varied drive machine.

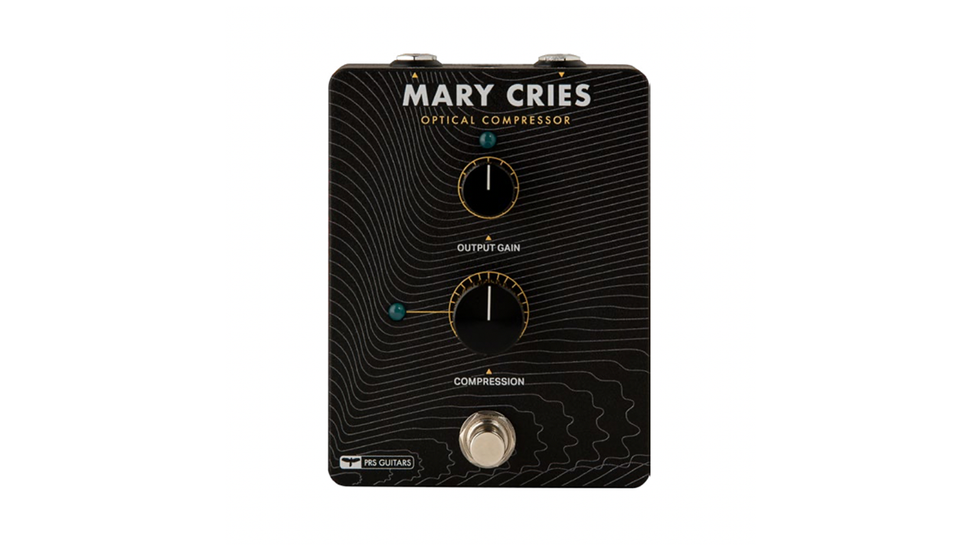

Mary Cries Optical Compressor

Like the Horsemeat, the Mary Cries comp hints at a possible PRS design team directive: That a guitar’s fundamental voice should always be able to be its best, most exciting self. That’s no surprise for a company whose instruments are typically so rich and sonorous. But like the Universal Audio Teletronix LA-2A optical studio compressor that inspired it, the Mary Cries succeeds so well that it could probably make a busted kazoo shine.

“The Mary Cries could probably make a busted kazoo shine.”

If you ever use a real LA-2A in a studio, you’ll never forget the way it fattens, flatters, and warms a signal. You’ll also be struck by how economical the layout is. Apart from a compression ratio switch, there’s a peak reduction knob (typically just called the compression control) and a make-up gain or output gain control. Even a novice can competently use an LA-2A using ears and intuition.

Building a pedal-sized optical compressor circuit does not automatically make it the equivalent of an LA-2A. That verges on the impossible. But the Mary Cries excels at the same tasks: adding body and excitement to a signal and enabling quick adjustments without overthinking the process. The Mary Cries reduces the control scheme of an LA-2A to just the compression and output gain controls (which are the controls studio engineers use most). But just as a studio LA-2A can dramatically recast a sound with these simple interactions, the Mary Cries has the capacity to completely alter the feel and force of an instrument—beyond adding sustain and mitigating the effects of nasty peaks.

Even modest compression settings on the Mary Cries also have the effect of thickening and tightening low- and low-mid frequencies, giving the perception of extra mass and resonance without overpowering the top end. Mary Cries also colors trebles with bell-like sustain that tends to decay in almost perfect balance with the fatter low end. Players often use comps to achieve balance between frequency band extremes, but the Mary Cries’ cohesiveness, if you’ll permit a food analogy, has the feel of a sauce where every ingredient shines brilliantly.

This ability to gather and highlight fundamentals and overtones in a balanced whole does wonders for simple and extended chords. And these tone composites can purr and growl gorgeously depending on where you situate your output gain. Incidentally, Mary Cries is a magnificent clean boost when you kick up the output gain and reduce the compression to a minimum.

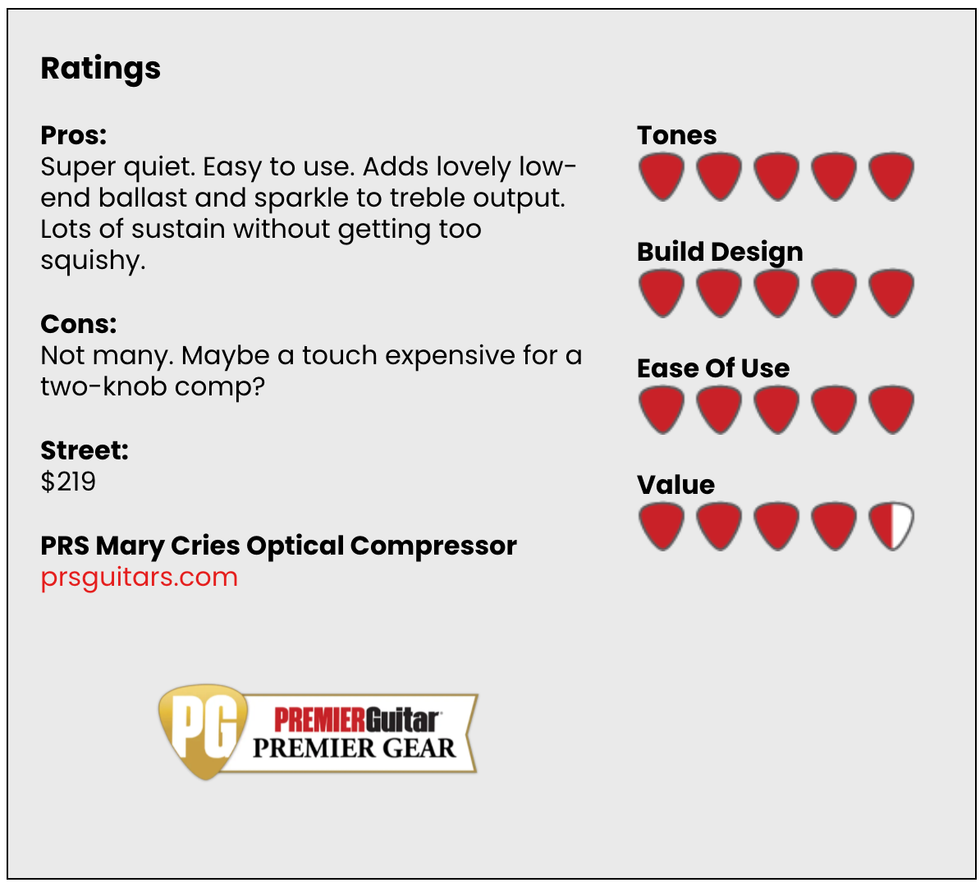

The Verdict

Mary Cries does a superb job of sounding and feeling transformative with very little fuss. It’s beautifully built, which manifests itself in the unit’s exceptionally quiet performance. At 219 bucks, it may seem expensive to players accustomed to other superficially simple comps. But I suspect even a cursory side-by-side play with many of these units would reveal much about Mary Cries’ nuance, elegance, and value.

Wind Through the Trees Dual Analog Flanger

Compared to its relatively streamlined siblings the Mary Cries and the Horsemeat, the analog, LFO-driven Wind Through the Trees flanger looks like a handful to manage. But for all the knobs that populate the Wind’s enclosure, it’s surprisingly intuitive.

Many contemporary, digitally attuned players will insist that a pedal this full of possibilities should come with presets. But the Wind Through the Trees’ analog interface is fluid and clear enough that you can move between varied settings with relative ease. That makes exploring the pedal’s myriad textures a flat-out joy—particularly because you can home in on very specific modulation profiles to suit a musical moment.

“One of the Wind Through the Trees greatest strengths is its ability to generate very mellow and hauntingly subliminal modulations.”

Flange is not an effect players typically associate with subtlety. But one of the Wind Through the Trees’ greatest strengths is its ability to generate very mellow and hauntingly subliminal modulations. These subtleties are made possible by the Wind Through the Trees very interactive, sensitive, and rangy controls. And, in my experience at least, the LFO mix, wet/dry output, and the very clearly labeled “added highs” controls are key to these textures.

Using these controls, you can, for instance, fashion a very understated modulation on LFO 1, blend in just a touch of twitchy, deep, high-rate modulation from LFO 2, add a touch of haze or brightness to taste with the added highs control, and then mix the sum into your signal with the very sensitive dry/wet knob. These are obviously not revolutionary means of control, but the way they work on the Wind Through the Trees feels surgical and gives you a real sense of command where some flangers feel monochromatic or purely chaotic.

But if chaos—or at least the surreal—is what you crave, the Wind Through the trees can deliver. For instance, very effective, weird-but-musical textures can be crafted by dialing closely adjacent but just offset rate and depth settings in the two LFOs, then setting their respective manual (or waveform delay) controls in opposition and cranking the regen to extra whooshy levels. Using the same scheme but mixing slow and fast rate settings in the two LFOs yields even stranger and more complex variations that combine hints of rotary speaker and ring modulation. And backgrounding these wild combinations by subtracting high end and using a dryer mix adds mysterious animation to chords and melody lines.

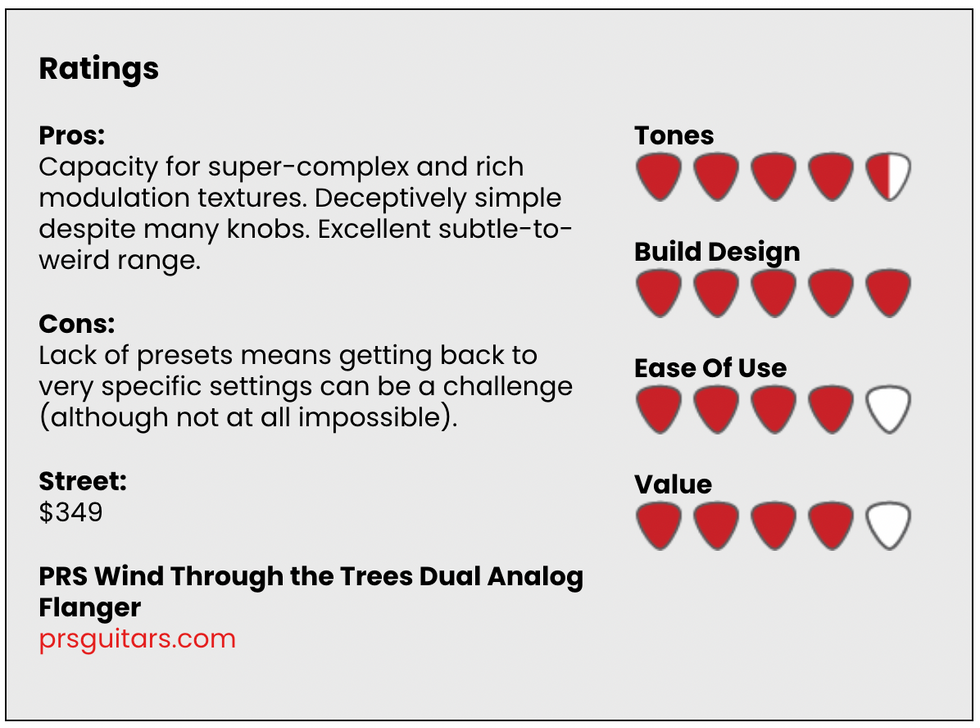

The Verdict

At about 350 bucks, the Wind Through the Trees is the most expensive of the new PRS pedals. And it’s understandable that some might perceive that price as high for an effect that’s, ostensibly, specialized. But the Wind Through the Trees proves how expansive a flanger can be when done right. There are lovely chorus-like sounds, plenty of intense vintage phase tones, and the deep but elegant and intuitive control set makes crafting complex modulations feel effortlessly creative.

Players accustomed to presets on a pedal with such broad capabilities may be bummed by their absence. And it’s true that moving between vastly different flange settings in the midst of a performance won’t always be a piece of cake. But in the context of song creation and in the studio, where you have the luxury of hunting for the perfect modulation color, Wind Through The Trees can be a potent musical companion.