From 2001 to 2009, Chicago’s pop-punk wunderkind’s in Fall Out Boy—vocalist/guitarist Patrick Stump, bassist Pete Wentz, guitarist Joe Trohman, and drummer Andy Hurley—rode a wave of rock stardom that took them to heights unfathomable by most bands. Four multiplatinum albums rocketed them to the top of the charts and thrust them onto arena stages worldwide. But the fame and accolades were matched by the highly publicized troubles of individual band members—including Wentz’s tabloid-plastered engagement and marriage to the already press-weary Ashlee Simpson. On November 20, 2009, the band announced they were going on indefinite hiatus and that they didn’t know if they’d ever play music together again.

The hiatus proved productive for all four bandmates. Though he endured harsh criticism from fans and the press, Stump embarked on a solo career that pushed his vocal prowess and guitar experimentation to new levels. Wentz developed a clothing line, a film production company, and other ventures while continuing to write music on his own. And Trohman and Hurley collaborated with members of Anthrax, Volbeat, and Every Time I Die in the Damned Things.

Then after months of rumors, in February of this year the Fall Out boys announced they had worked out their differences and were working on a new album titled Save Rock and Roll. Refreshed and reinvented, the album features the band’s trademark vocal hooks, cleverly crafted riffs, pedal-laden ambience, and a tighter rhythm section. Songs like “The Phoenix” and “My Songs Know What You Did in The Dark (Light ’Em Up)” still thrive on the youthful vigor that put the band on the mainstream map, while the album as a whole showcases more maturity and enhanced musicianship. Getting a second chance that’s seldom granted in the music world, the band has again seen its work shoot to the top of charts all around the world, and the subsequent tours are sold out.

While Fall Out Boy’s fans are rejoicing as the foursome emerges from the ashes, no one appears happier about the return than the guys themselves.

Joe Trohman's signature Squier Tele features a '70s-style Strat headstock and a Tele Deluxe-like pickguard loaded with two humbuckers, a single-coil, a 3-way selector, and two sets of volume and tone knobs.

How does it feel to be back together and

on top of the world again?

Patrick Stump: It feels so good to be back

doing this with these guys. It’s funny, because

I feel like we never understood where we

were or how we were doing and then we

took a step back and realized that we’re making

music for—and affecting a lot of people.

I’m very happy to be back doing it.

Joe Trohman: It feels great to be back and to have made the changes we needed to make. We weren’t running very well as a band before the hiatus—communication skills collapsed between us and there were a lot of issues. Going on that break and starting new projects really helped us be more confident, and it helped us gain a lot of mutual respect for each other and our abilities, which became a really integral part of us getting back together. Now we’re in just a better place. Everyone is too old to get angry about stupid things, which is awesome. Everyone just trusts each other.

Pete Wentz: It feels crazy. It’s really rare that you get a second chance to do something—and especially something so fun, fulfilling, and interesting. It’s something that we’re not taking for granted in the least this time around.

What was it like the first time you all

stepped back in a room together and

played music?

Trohman: We met up at Patrick’s house in

his backyard studio, and I was a little nervous.

Then we started playing and, at first, it was like

the worst Fall Out Boy cover band imaginable.

We hadn’t played together in so long and it was

just terrible. It was pretty weird for a minute,

but once we shook the dust off it was better

than the last time we’d ever played—back

when we were a well-oiled machine.

Stump: Yeah, we sucked—we didn’t remember anything. At the second practice, we fell back to just about as good as we were, and then the third practice I feel like we sounded pretty great—even better than we were. It feels like we’ve been able to go back in time to fix our mistakes.

Wentz: The first rehearsal was definitely shaky, but once it started clicking we all knew that we had potential to be better than we’d ever been.

What were the biggest lessons you

learned from the hiatus?

Stump: The biggest thing for me was going

out and doing my solo stuff—that made

me a lot more confident as a frontman. I’ve

always been a reluctant frontman because

I’m a shy guy—for years I was just hiding

under my hat the whole time—but I went

out on my own and had to do it.

Trohman: I went right from FOB to other projects, and it made me learn how to work with other people. Anyone who plays in the same band for a long time should play with other people, because you can learn so many things from different players’ styles, tastes, techniques, and work ethics. I learned how to be a better songwriter and a better musician and how to play better with others—both musically and as a person. I learned how to be a better bandmate, and I looked at a lot of my bad tendencies and neuroses and figured out how to change them for the better. I think it took being in other bands to realize that I really wanted to be in this band more than anything.

Wentz: During our time off, I was making a lot of music on my computer—it was more of an electronic kind of sound. I didn’t play as much bass as I wanted to in the break, so I knew I had to get back into my playing before we even began to approach a comeback. I didn’t want to show up on day one and not know what I was doing, so I really stated working on my technique, playing with a metronome and taking steps to make myself a better player.

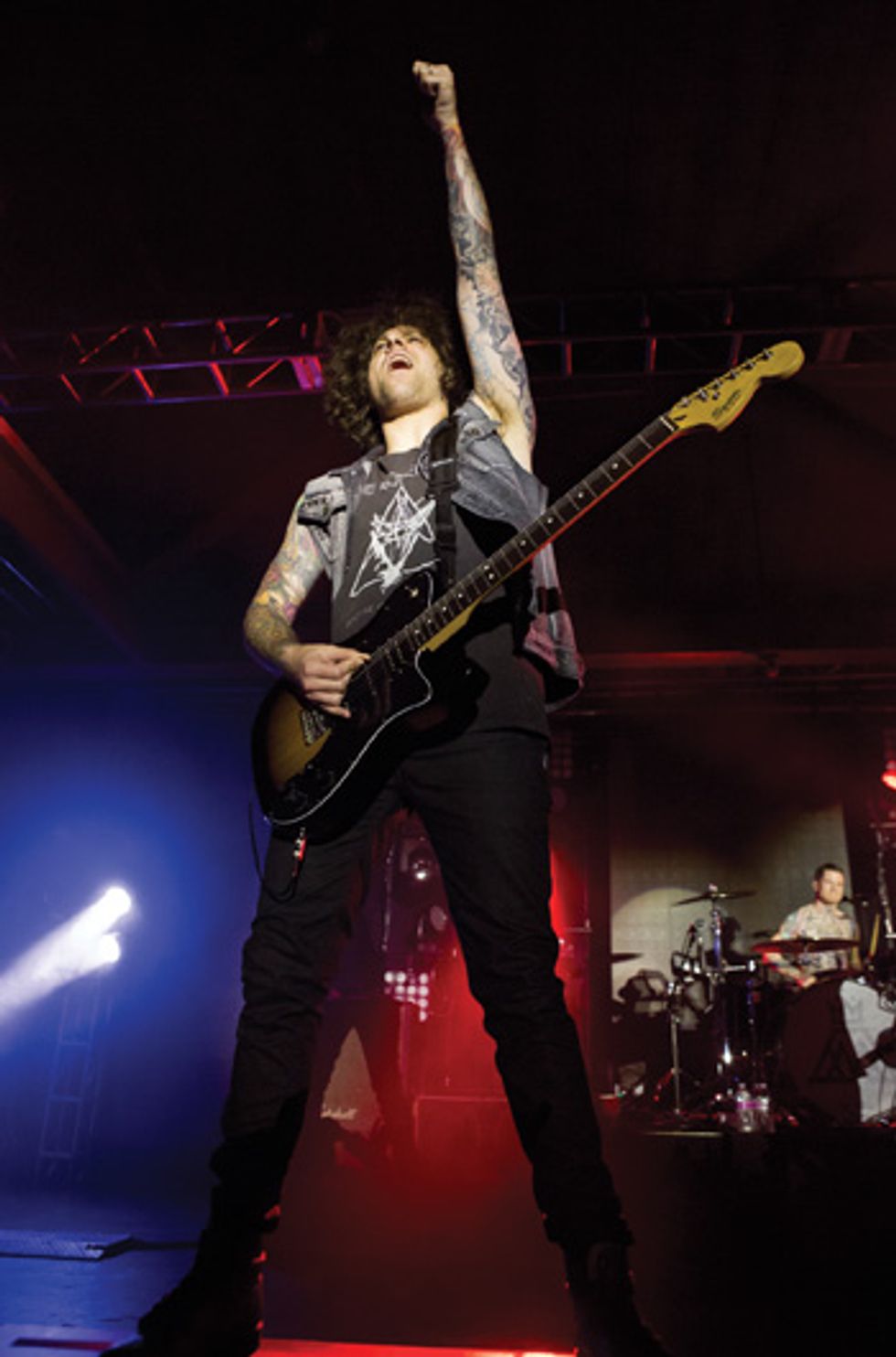

Patrick Stump belts it out while holding down the

rhythm at a recent Fall Out Boy gig in Seattle.

What was the writing process like for

Save Rock and Roll?

Trohman: On prior albums I would write

very little—I felt very unintentionally discarded.

Pete and Patrick would write so

much that, by the time we’d be ready to

record, I wouldn’t have much of a voice on

the record. That’s what caused the greatest

frustration for me. This time around, I was

a big part of the process. I live in New York

and they live in L.A., so we wrote ideas and

sent them back and forth. We took each

other’s tracks and worked on them and

kept growing them. That’s just how we do

it now.

Stump: It was a very collaborative record. I felt for a long time that I was overpowering in the studio for our previous records. I still like to be the central hub for the songs, but more than any other record this was all of us working together. I would wait for everyone’s ideas and then put them together, and I would only write in the studio when parts needed it. At this point, it’s hard for me to recall who wrote what—but that’s how a band should be right?

Wentz: It felt good to approach songwriting in a new way, and we all really stepped it up so that the burden wasn’t always on Patrick or anyone specific to come up with something. Joe wrote more on this album than he had on any records prior. Also, working with producer Butch Walker taught us that less is more and that when you give frequencies space, they sound bigger. It was a big change to go down that road.

It sounds like you approached your instruments

much differently on this album.

Stump: For a long time I had taken a

lot of the melodic leads in the songs—the kind you would hum. That was

my thing. If I wrote the melody of a

song it would already be done, and

that wouldn’t leave a lot of room for

Joe to play around with. So this time

around it was important that Joe had a

strong voice, because he’s such a great

player. Joe has some really great guitar

moments on this record, and I focused

on a lot of atmospheric stuff. I was

cramming guitar everywhere on our last

record because I had been really into

polyrhythm and syncopated riffs—to

the point where I was quintuple tracking

all of my guitar parts. This was a lot

simpler playing for me.

Trohman: I think what I was most concerned with was slowing down and feeling, versus speeding up and fitting in as many notes as possible. I was trying to do things that made the guitar sound like it was singing rather than just quickly repeating the same thing. I was trying to take things out of tune and discorded and make them sound musical. You can learn all the scales and modes that are out there and learn to play as fast as possible, and that’s impressive as hell, but if it doesn’t have some emotion and feel behind it, it’s not impactful. I got back to playing the blues and I relearned old Hendrix stuff and went back to my roots. I played a lot of things that I wouldn’t normally play in Fall Out Boy.

Wentz: More than ever, I really just focus on the rhythm and figuring out what the song needs from the bass. I don’t need to play flashy lines or stand out as much, because so much is already going on in the music. I’m writing parts that are in the pocket with Andy’s drums and create a strong foundation for the other guys. I think locking up with him and strumming with the kick drum has enhanced my playing and made me a better player. Live, Andy plays a lot of fills that he doesn’t play on the album, but he always gets back to the one and nails it. Andy is definitely the glue of the band—he just doesn’t mess up.

Fall Out Boy bassist Pete Wentz says it was important for his signature bass to be part of the Squier

series because he wanted it to be affordable to young players.

Joe and Patrick, in the past you guys traded

off playing lead and rhythm guitar on different

songs. That seems to have changed.

Trohman: We’ve kind of reevaluated our

process. We looked at how it sounds at the

front of house when we switch back and

forth from lead to rhythm and figured out

that, sonically, it can make it hard to come

through at some points. So now I’ve taken

over all of the lead stuff, unless there’s something

that’s difficult for him to sing and

play. I enjoy playing rhythm and just grind

out on it and headbang to it a bit, but I’ve

kind of evolved to playing the lead riffs. I

enjoy serving the song what it deserves.

Stump: I still play some leads, but what we landed on was that Joe has a style that can accomplish more or less any of those great lead-guitar lines. In the song “I Slept with Someone in Fall Out Boy and All I Got Was This Stupid Song Written About Me” [from 2005’s From Under the Cork Tree], there is a little arpeggiated tapping part that I would do while I was singing, and every night I was just making things so difficult for myself by playing that. It was like tapping your head and rubbing your stomach. So now Joe plays that stuff and it makes the whole band tighter because I can lock in rhythmically with Andy and Pete.

Joe Trohman’s Gear

Guitars

Squier Joe Trohman Telecaster, Fender

Blacktop Baritone Telecaster, Gretsch G3140

Historic, Reverend Warhawk III HB, Fender

Wayne Kramer Signature Stratocaster,

Fender Custom Shop acoustic

Amps

Two Orange Thunderverb 50s, Sunn Model

T, Divided by 13 FTR 37, 1969 Marshall 8x10

cab, Hiwatt 4x12 cab

Effects

Boss Gigadelay, Way Huge Aqua-Puss, Earth-Quaker Devices Disaster Transport Jr., Earth-Quaker Devices Grand Orbiter, EarthQuaker

Devices Hummingbird, Catalinbread Dirty

Little Secret, Catalinbread Heliotrope, Electro-Harmonix Pulsar, DigiTech Whammy, Ibanez

ES-2 Echo Shifter, TC Electronic Hall of Fame

Reverb, RJM Music MIDI foot controller

Strings and Picks

Dean Markley Blue Steel sets (.011–.052),

medium-gauge Dunlop Tortex picks

Patrick Stump’s Gear

Guitars

Gretsch G5135CVT-PS Patrick Stump

“STUMP-O-MATIC” Electromatic Corvette

signature models

Amps

Marshall JCM800, Vox AC30

Effects

Line 6 POD

Picks and Accessories

Dunlop medium-gauge picks,

Peterson strobe tuner

Pete Wentz’s Gear

Basses

Custom Fender “Michael Jordan” Precision

bass, Squier Pete Wentz Precision bass

Amps

Orange AD200 head driving

Fender 810 PRO V2 8x10 cab

Effects

Tech 21 SanAmp DI,

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff

Strings

Dean Markley heavy strings

At this point, how would you guys say

you’ve evolved the most as musicians?

Trohman: I’m at a point where I’m so hungry

to learn new stuff. I can play so much

where I don’t have to think about it at all,

so I’ve been looking for things to challenge

me. I want to find some new tricks and

weird techniques that I can apply to my

playing. I definitely don’t think I’m anywhere

close to being done learning, and I

think that if you do hit a point where you

stop learning then you should just stop

playing music in general. I wish I could go

back and tell my younger self to learn theory,

chords, picking patterns, and rudiments, and then just don’t think about it when

you’re playing.

Stump: Not to toot my own horn or anything, but I think I’ve evolved into becoming a pretty rad little rhythm player. I never sat at home and shredded and ran scales for hours—I’ve always been a songwriter, but mainly by necessity. I developed all of my personal playing hallmarks in that span, and I think it’s a good thing to teach yourself—because you’ll develop your own style. A lot of my origins come from my love of funk. Over the years, I think I’ve become pretty well rounded.

Wentz: I’ve grown to accept the rule that I’m playing bass—and that it’s not just a guitar with four strings. I’m part of the rhythm section and, more than ever, I’m focusing on that and how to make myself better in that role. The average person doesn’t always hear the bass. You subconsciously hear it, but if it wasn’t there you’d know it wasn’t there. The bass can be a lot of ear candy in a great way.

Each of you has a line of signature guitars—that must be pretty cool.

Wentz: It’s crazy for me to be able to go

in and design it from scratch—it’s really

one of the greatest honors a musician

can experience. When I first started playing

and would go into Guitar Centers, I

wanted the freshest basses and guitars they

had, but as a kid they’re just too expensive

to walk in and buy. I couldn’t pay $800

for a bass I was just going to play in my

garage and learn other people’s music on.

It’s important to me that it’s part of the

Squier series—because those are the basses

that kids are going to be able to buy. Kids

come up to me and tell me they’re playing

my bass, and I remember being on the

other end of that. And to be able to share

that with guys like Sting and [Green Day

bassist] Mike Dirnt is amazing—though

I’m probably the lowest guy on the totem

pole.

Trohman: It’s beyond words how exciting it is—I would have never dreamed of it as a kid. To be honest, I still can’t believe it now. The people at Fender are so amazing to work with, and it’s such a trip to have other players play on guitars that I helped design.

What were the first guitars you

guys owned?

Trohman: Mine was a Harmony Barclay

Bobkat guitar with a matching amp. I

got them both for, like, $50 and just

played away on it any chance I could get.

Stump: It was a black Epiphone that my stepbrother lent me, and it was in really bad shape. I still have it. The first guitar I ever bought, though, was a silver Gibson SG.

Wentz: My first bass was a cheap knockoff that said “Naugahyde” on the headstock. I had never heard of it before—but I really don’t think anyone has [laughs].

Who are your biggest musical

influences?

Trohman: Jimi Hendrix, [Depeche

Mode’s] Martin Gore, Jimmy Page,

Freddie King, Reverend Gary Davis, the

old Delta blues guys, Johnny Winter,

Kirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Greg

Ginn, Eric Clapton, and Billy Gibbons.

Stump: One of the first people who got me okay with not being a shredder is Elvis Costello. He always said he was more attracted to chord changes than the big moments of shredding. Prince is a huge influence for me—he’s a shredder, but he’s also a metronome. [Pantera’s] Dimebag Darrell, also—because he was all about feel, and that’s rare in metal.

Wentz: [Guns N’ Roses’] Duff McKagan is probably my biggest. When you listen to him you might think that he’s doing what you’d expect from the bass, but then he puts in a run or a fill that just blows my mind. Mike Dirnt is also huge for me. When you’re playing in a three-piece, the pressure is so big for bass. You have to be the backbone and then some.

So what’s next for Fall Out Boy?

Wentz: We’re so excited about the reception

that we’ve gotten with this album

that we definitely want to move forward

and make another record and keep touring.

But at the same time, the space we

gave ourselves to make this album made

us better as a band and better as songwriters.

So we have this tour and festivals

overseas, and then a tour with Panic! at

the Disco. All that time should give us

some space to write some new music.

We’re definitely always forging ahead—we’re just happy to be back.

YouTube It

Patrick Stump, Joe Trohman,

Pete Wentz, and Andy Hurley

pay tribute to Spinal Tap—

complete with malfunctioning

chrysalis pods and a guest

appearance from bassist

“Derek Smalls” (Harry

Shearer)—in this memorable

appearance on Conan.

In this 2008 clip from the Live

in Phoenix DVD, the Fall Out

boys perform “Sugar, We’re

Going Down” to a packed

stadium.

Stump, Wentz, and Trohman

grab some flattops and prove

they can cut it live without all

the fireworks and blaring amps.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)