We’re back to Johann Sebastian Bach for this lesson. We’ll focus on an 18-measure passage from one of his violin partitas with two goals in mind: First, it’s a fabulous finger exercise that will challenge both your hands. It’s also a case study in just how much you can communicate with a single-note line.

Don’t know a partita from a fajita? No worries. The lessons here are relevant for any type of composition or improvisation. (But in case you were wondering, a partita is just another name for a suite: a group of compositions that work together as a set.)

Point: Counterpoint

J.S. Bach is famed for his use of counterpoint: the way he wove multiple independent melody lines into glorious tapestries of sound. You hear it in all his compositions, from the massive choral works to compositions for solo instruments such as harpsichord and lute.

Harpsichord and lute can play multiple melodies simultaneously. But what did Bach do when composing for an instrument that can only play one note at a time, such as the flute? Hear for yourself!

Even though you never hear more than one note at a time, you perceive the underlying chords. At times the flute leaps between high notes and low notes, suggesting two simultaneous melodies. The music never gets rhythmically boring, even when, for example, you get nothing but an unbroken string of 16th-notes from the beginning of the video until the 01:20 point. We’ll see how Bach accomplishes those things in our violin excerpt (Ex. 1).

Click here for Ex. 1

Stretch and Bend

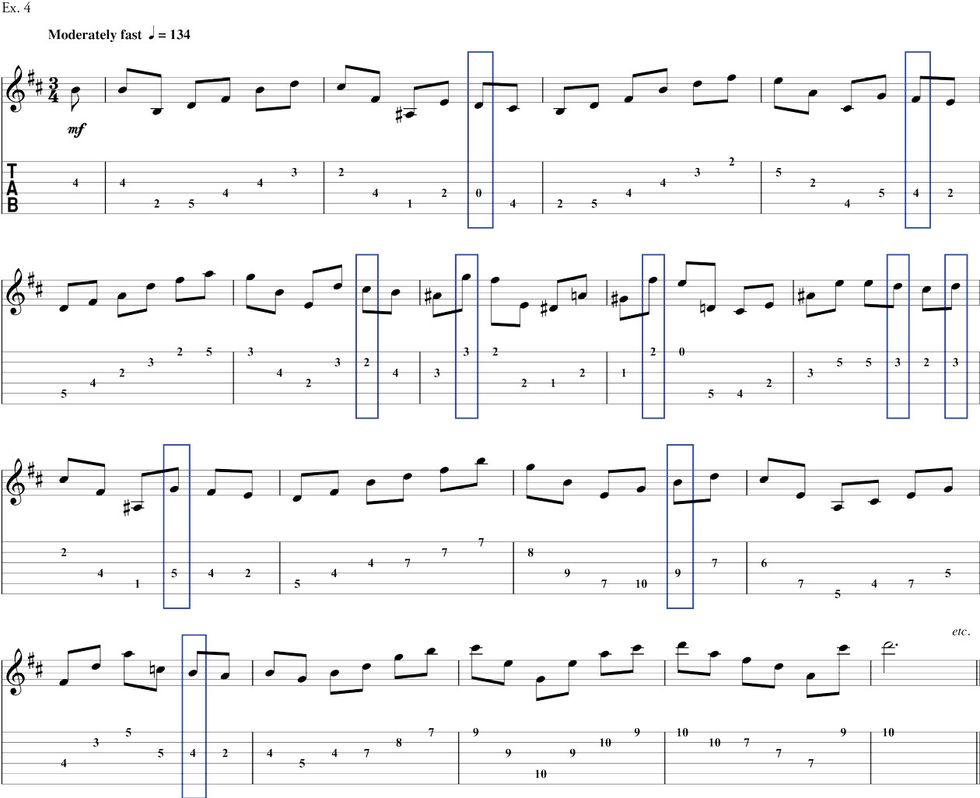

First, let’s consider this as a technical exercise. This guitar version is an octave lower than the violin original. The tab shows my favorite way to finger this passage, though you may get better results shifting some notes to other strings. Composers didn’t use metronome indications in Bach’s day, probably because there were no metronomes. But the name of this section of the partita—“Corrente”—tells us that it should be played at a lively “running” tempo.

In some ways, the first two measures are the trickiest ones, because you must play consecutive notes across the 4th and 3rd strings using the same finger. (I recently wrote a lesson on this very topic.) Another challenge is “spider-y” fingerings that don’t conform to common guitar scale patterns, as in measures seven and eight. (The exercises in this lesson can help you develop the needed finger independence.) You also need to make some speedy position shifts, as in measures 11 and 15. (This lesson includes some tips for fast and efficient position changes.)

I play the examples fingerstyle, but they work great with a pick too—just brace for some challenging string-skipping. Aim for smooth, connected phrasing. A listener shouldn’t be able to tell that a sequence of notes required a twisty fingering or a tough position shift. And of course, start out at a slow tempo!

If you stop here, you’ll have a challenging exercise—great! But read on for an analysis of how Bach says so much with a single-note line, using techniques you can apply to your own composition and improvisation.

The Art of the Arpeggio

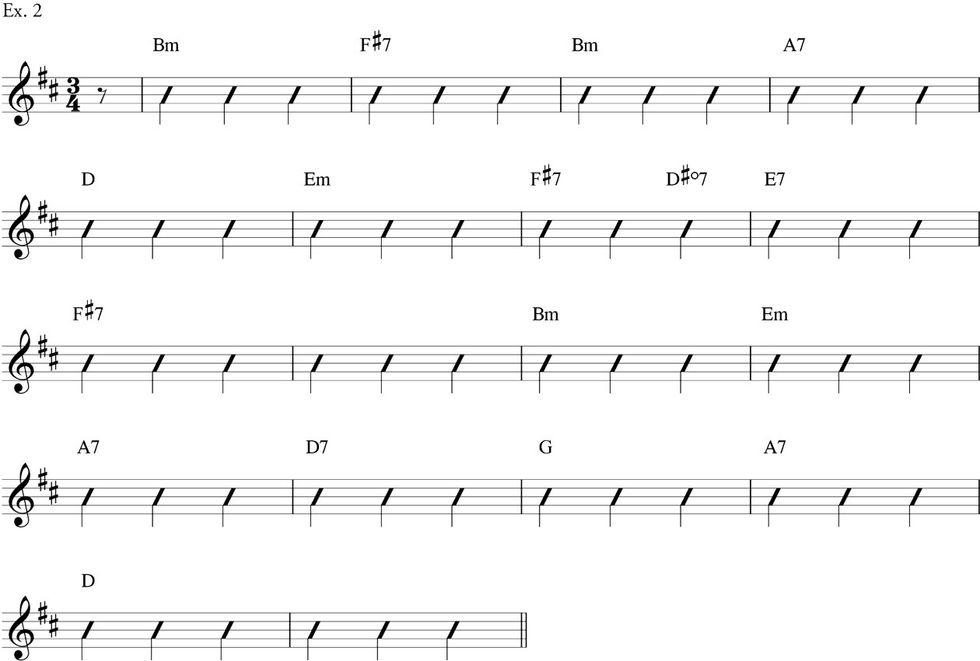

Even with this single melodic line, Bach lets you hear the underlying chords, mainly through arpeggios—sequences of notes that convey chords as a string of notes. Classical musicians don’t think of “chord progressions” in the way pop musicians do, but if you indicated these harmonies pop-song style, it would look like Ex. 2. In the accompanying audio clip, I add strummed chords to reinforce these harmonies. But these are superfluous—the melody already communicates them.

You can hear the 18-measure passage as two long phrases. The first phrase is 10 measures in length, while the second is seven measures long. We’re so accustomed to four- and eight-measure phrases in music that these asymmetrical phrase lengths sound fresh and unpredictable.

Notice how not all the “chord changes” are of equal length. Bach sets up one harmony per measure as a pattern, but then he breaks it up with a two-chords-per-measure change in measure seven, and a longer sustained harmony in measures nine and 10. “Harmonic rhythm” is the term for the rate at which harmonies change. Setting up a steady harmonic rhythm, but then deviating from the expectation it creates it is one of the ways Bach adds rhythmic excitement, even in an unbroken chain of eighth-notes or 16th-notes.

Chords/Not Chords

You’ve heard plenty of fast guitar arpeggios—they’ve been a shredder’s staple since the 1980s. A chord progression played with light-speed arpeggios may be more dramatic than simply strumming the underlying chord, but the harmonic information is the same. But Bach doesn’t use long, unbroken blocks of arpeggios—they’re interspersed with dissonant notes and short scale patterns. In Ex. 3, the red boxes indicate arpeggios that outline a single chord.

Ex. 4 flips the equation, indicating passing dissonant notes with blue boxes.

Notice how irregularly the boxes appear. You never know exactly which note is coming next.

The Compound Line

For me, Bach’s most amazing magic trick is implying two melodies with a single line. Imagine a film of an artist painting two different canvases on adjacent easels: a few strokes on this one, then a few strokes on the other. If you speed up the film, it might look like twin artists painting simultaneously. Bach does something similar with a line that leaps between registers to create an illusion of two simultaneous parts.

Let’s zoom in on the first four measures. In Ex. 5, I split the music between two guitars, one covering the low notes and one snagging the high ones. When one part stops moving, it sustains a chord tone while the other part moves. Of course, you don’t actually hear those sustained notes in the original version—but it’s easy to imagine that you do. This “two melodies at once” technique is called a compound line.

Click here for Ex. 5

The Ups and Downs

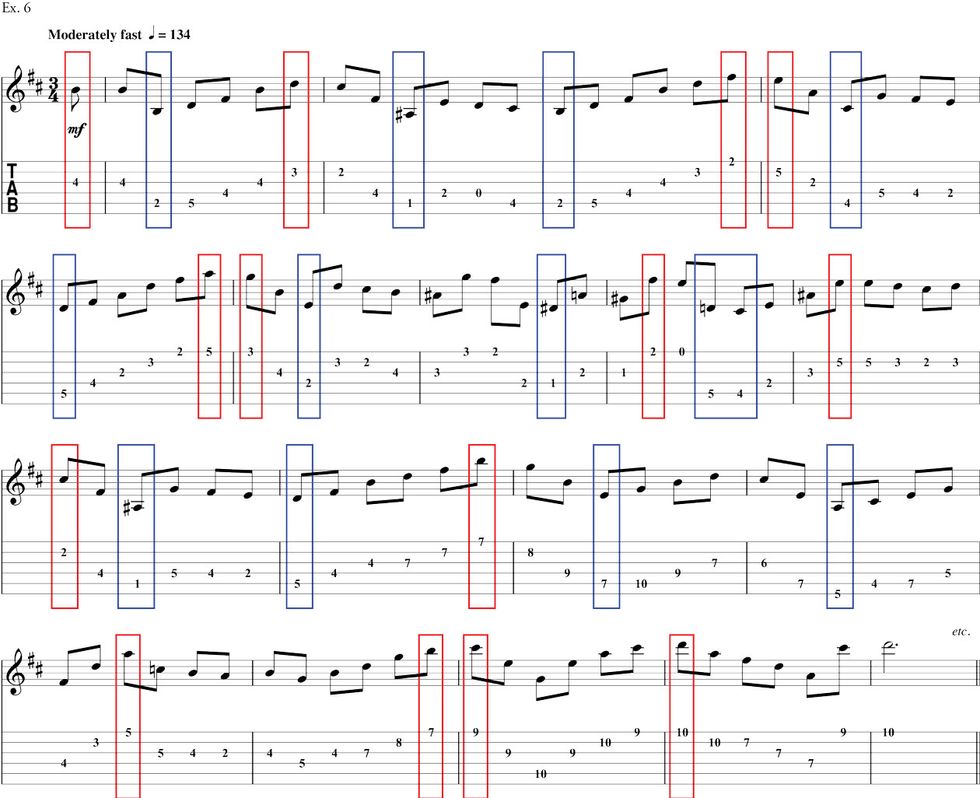

Finally, let’s see how Bach makes strategic use of register—the distribution of high notes and low notes. You don’t get the full range right away—he gradually introduces successively higher notes, climaxing with the high D in the final two measures. In Ex. 6, I’ve indicated the highest notes with red boxes and the lowest notes with blue boxes.

Try playing only the red-box notes as if they were a melody, and then try the same with the blue boxes. The resulting lines make musical sense on their own. They’re like points on a road map, or maybe an architectural blueprint. You get a sense that there’s a master plan.

Your Inner Bach

None of us can compose as well as Bach, let alone improvise Bach-quality lines. Yet chances are these concepts are applicable to your own music. If you’re using an unvarying pattern, might it be more dramatic to set up an expectation, and then violate it?If a melody consists mostly of chord tones, would it be more exciting to break it up with non-chord dissonance? If you’re using only four-measure phrases, could you introduce some three-measure or five-measure phrases? If your part climbs straight up or down a scale, could you liven it up with daring leaps? Asking yourself questions like these may yield cool and surprising answers.

By the way, the image at the top of this column is Bach’s original manuscript for this music. If you’d like to explore the entire partita in standard notation, you can download a public-domain score here. There are many fine performances online—just search for “J.S. Bach Partita in B Minor solo violin.” Here’s a fine one by Gidon Kremer. (Our section starts at 07:19.)