Advanced

Intermediate

• Understand the mechanics of the half-whole diminished scale.

• Use basic triads to break from the fear of symmetrical sounds.

• Learn how to use bebop phrasing with wide intervallic leaps.

It's nearly impossible to improvise over a tune without hitting a dominant chord. They are ubiquitous in rock, pop, jazz, country, and nearly every other type of Western music. I'm sure you've heard the phrase about how all music is based around tension and release? Well, I want to teach out how to make the tension cooler and the release more musically satisfying.

Instead of walking through basic 7th chord arpeggios, which have their place, I want to investigate the half-whole diminished scale and the four major triads that are inside it. We can all get our head around triads, right? Let's start with a quick review of the half-whole diminished scale.

The half-whole diminished scale is a symmetrical scale created by alternating half- and whole-steps, which creates an eight-note scale. In C this would be C–Db–Eb–F#–G–A–Bb. The other defining factor is that—much like diminished chords—this scale repeats every minor third. In other words, the C, Eb, Gb, and A half-whole diminished scales all contain the exact same notes. Not coincidentally, those four notes also outline the major triads included in the scale.

Because of the symmetrical nature of the scale and the fact that it repeats itself, there are a total of three half-whole diminished scales: C (which is the same as Eb, Gb, and A), Db (which is the same as E, G, and Bb) and D (which is the same as F, Ab, and B). In essence, once you've learned all three scales and have gained a strong sense of how this scale sounds, you will able to apply it to any dominant 7 chord from any root.

Why Not Just Play the Scale?

Great question. While there is absolutely nothing wrong with using scales to improvise, I find that isolating and combining the major triads in the scale can provide a fresh perspective and distinct color when playing over dominant chords. It gets me away from familiar sounds and patterns. Using the triads in combination creates a strong dominant sound that's begging to resolve, while also often sounding mysterious and far less like you're just running up and down the scale.

Diminished Resolutions

In the following examples we'll be looking at how to use major triads from the diminished scale in combinations of two to four and hear how they resolve to major chords, minor chords, and other dominant chords. Worth noting is that for most of the examples we'll be using the G, Bb, Db, E major triads to resolve to some sort of C, Eb, Gb, or A chord. The reason we're able to do that is because the scale repeats in minor thirds. Therefore, G7 can be treated the same as Bb7 (and can resolve to any type of Eb chord), which can be treated the same as Db7 (and can resolve to any type of Gb chord), which can treated the same as E7 (and can resolve to any type of A chord). Let's get started!

Feel free to learn these examples using positions and fingerings that feel comfortable to you. As long as you're paying attention to the quality of your sound and playing the lines with a strong sense of rhythm and phrasing, there is no single "right" place to play these on the guitar. The tabs are merely a suggestion.

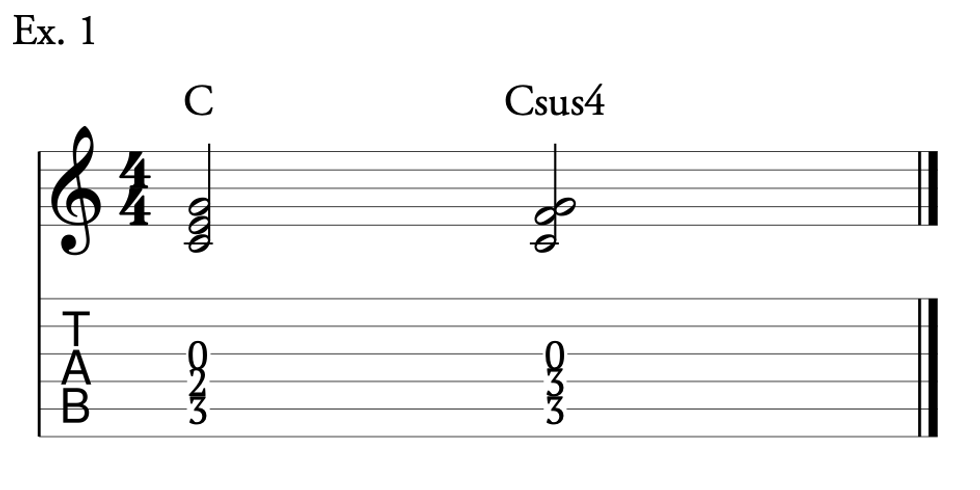

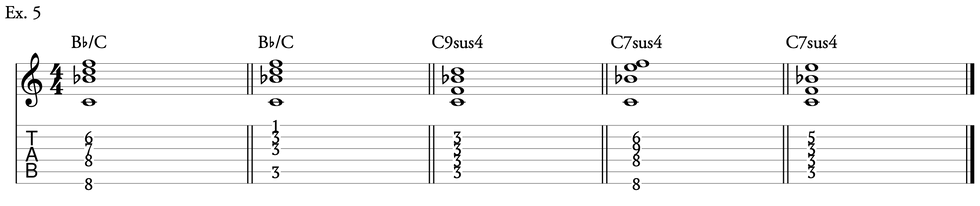

We'll start off simply in Ex. 1 with a IIm-V7–I in the key of C. On the Dm7 chord we have a line essentially constructed around the arpeggio with a bebop sensibility. Once we arrive at the G7 chord, notice that while there is no major triad played in its entirety sequentially, the line is constructed using the notes of a Bb major triad and a Db major triad. As we resolve to Cmaj7, there is a slight suspension of the #5 (G#) that quickly resolves to the natural 5 (G).

Dominant Chord Domination Ex. 1

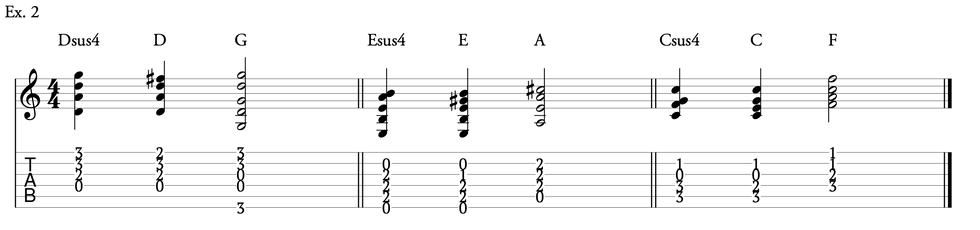

In Ex. 2 we clearly outline and connect a C triad to a Gb triad over the A7 chord resolving to Dm7. This time on the G7 chord we use the two other major triads from the scale that we did not use in Ex. 1: E and G. In this measure the E triad is played in its entirety in 2nd inversion and for the last two beats we use a combination of notes from the E and G triads resolving to the 7 (B) on the Cmaj7 chord.

Dominant Domination Ex. 2

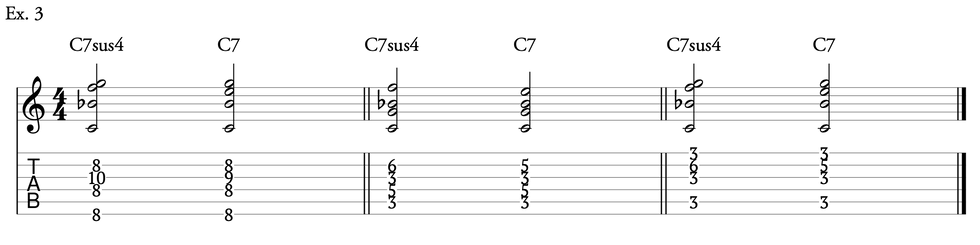

Ex. 3 changes key, this time playing over a IIm7–V7–I resolving to Ebm6. Notice that we're able to draw from the same pool of triads for Bb7 as we did for G7. We're still using two major triads on the dominant chords, this time E and Bb, resolving to the natural 6 (C) of the Ebm6 chord.

Dominant Domination Ex. 3

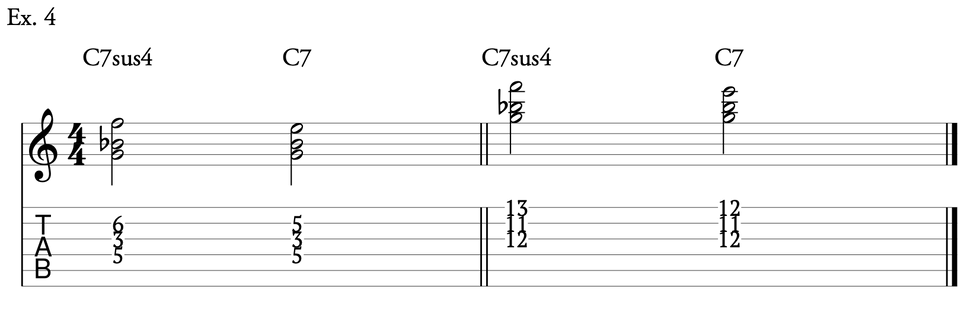

Next, we get a chance to hear the other two triads (G and Db) played over the Bb7 chord, this time resolving to Ebmaj7 instead of Ebm6 (Ex. 4). It's worth noting how well this dominant sound can resolve to both major and minor chord qualities. Here, we also begin to break things up with eighth-note triplets and larger intervallic leaps.

Dominant Domination Ex. 4

Ex. 5 gives us our first chance to hear a dominant chord moving to another dominant chord before resolving to the I chord. Pro tip: You can change any IIm chord to a dominant chord to create a half-step move to the V7. On the D7 chord we hear a syncopated Ab triad followed by a B triad with a D natural leading into it (the note is not outside of the chord, but in this instance still functions like an approach note). Next, the line combines the notes of an E and Db triad on the Db7 chord, finally resolving to Gbmaj7 with a line built around seconds and fourths and highlighting the #11 (C).

Dominant Domination Ex. 5

In Ex. 6 we have a similar progression to the one in in Ex. 5, but this time each dominant chord is two measures long instead of one and we resolve to a minor chord instead of a major chord. Because of the longer duration of the dominant chords, we're able to utilize all four major triads on each dominant chord (F, B, D, and Ab on B7; G, E, Db, and Bb on Bb7).

Dominant Domination Ex. 6

This one tackles a tricky part of George Shearing's song "Conception" using our triadic approach on the quickly descending dominant chords (Ex. 7). I find this approach helpful on this type of progression in terms of playing a line where the trajectory moves independently from the downward direction of the chord movement. In this example we get into some more challenging rhythmic phrasing and generally use only one major triad on each dominant chord.

Dominant Domination Ex. 7

Finally in Ex. 8 we see an often-encountered progression where the root motion is V–I from beginning to end. Here, we are back to using two triads per dominant chord (but this time with some approach notes) mixed with a strong bebop sensibility.

Dominant Domination Ex. 8

As you can see, the diminished chord gets a bad rap for being overly complicated and too pattern based. By thinking of more melodic fragments (triads!) you can tackle more difficult harmonies with ease and give your lines a fresh perspective.