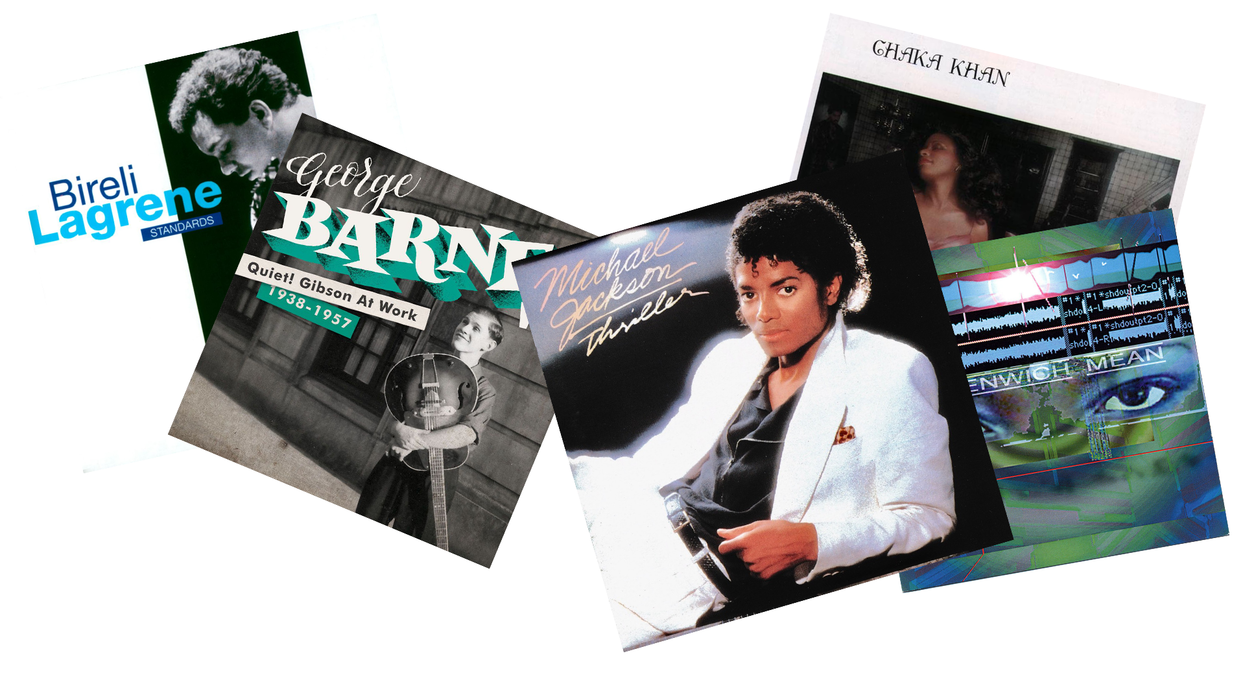

John Scofield is the embodiment of fusion. When he began recording as a leader in the late '70s, his fluid blend of jazz, bebop, blues, rock, and country music must have presented a marketing nightmare for the label. Scofield attended the prestigious Berklee College of Music, but his influences are anything but expected, and his sophisticated sound incorporates deep groove influences. As an improviser, he reveals an effortless command of modern, angular, and chromatic vocabulary.

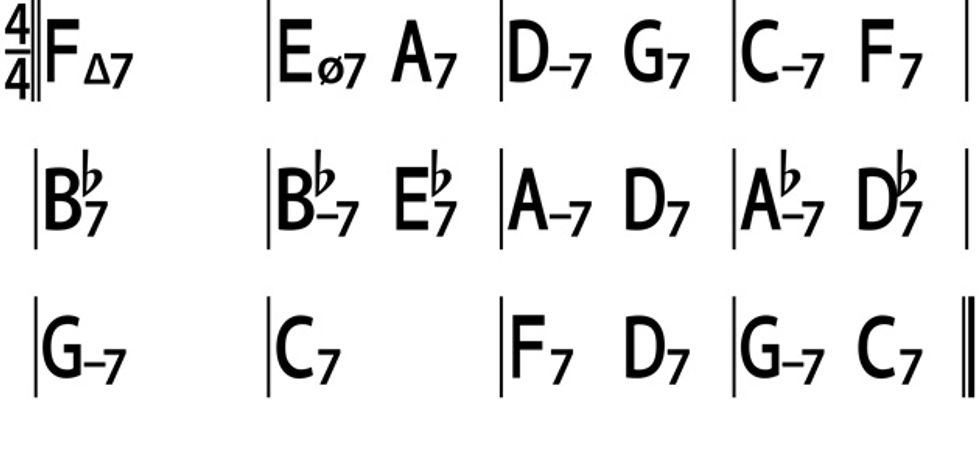

For this column, I've recorded a simple bass loop over a funky 16th-note shuffle groove. The line indicates the A Dorian mode (A–B–C–D–E–F#–G), but since the harmonic information is so sparse, it's pretty easy to insert other sounds and make them work.

Nailing Scofield's tone is half the battle. Fellow fusion master Scott Henderson recently said that you can't play jazz with a humbucker and a little bit of overdrive and not sound like Sco. There's some truth to that. Here, I used the bridge pickup on my Joe Barden T-style and rolled the tone knob back about halfway. This is going into a mildly overdriven amp I can control with both the guitar's volume knob and picking dynamics. I've also incorporated some pretty extreme chorus—a key ingredient in Scofield's signature sound.

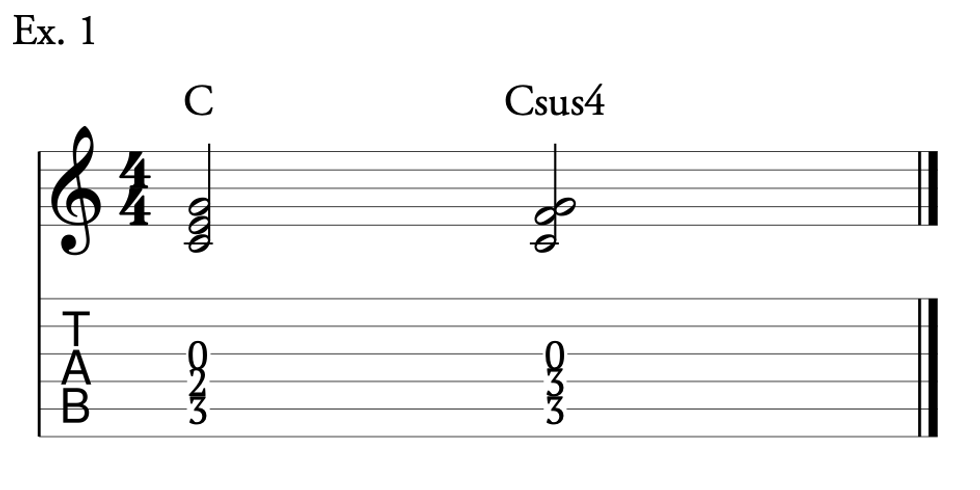

Ex. 1 begins by outlining an A7 arpeggio (A–C#–E–G), though beat two goes a little outside by hitting a D# that hints at the A Lydian dominant scale (A–B–C#–D#–E–F#–G). Double-stops play a big role in Scofield's playing, and we get a taste of this in the second measure, which offers both a tritone (F# and C) and a major seventh interval (E and D#). Bonus: Dig the contrary motion in the second and fourth measures!

Ex. 1

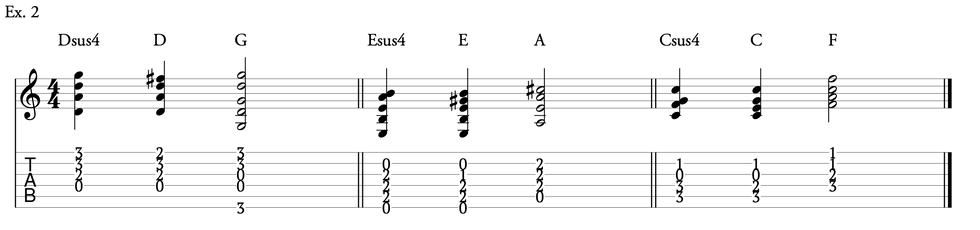

We explore more double-stops and fourths in Ex. 2. The double-stops in the first measure could be analyzed theoretically, but it's likely Scofield was just playing around with the pentatonic scale and then simply moved up a half-step to create tension.

The second measure features more traditional bluesy phrasing, before shifting up to Bb minor pentatonic (Bb–Db–Eb–F–Ab). As before, this could be analyzed, but it makes more sense to label it "sidestepping," which is simply playing a half-step higher to create tension before shifting down to resolve. This sidestepping idea can be seen again in the fourth measure. You can think of this as a diminished scale, but it's a lot easier to imagine shifting the same scale up a fret.

Ex. 2

John Scofield Performs 'Quiet And Loud Jazz'

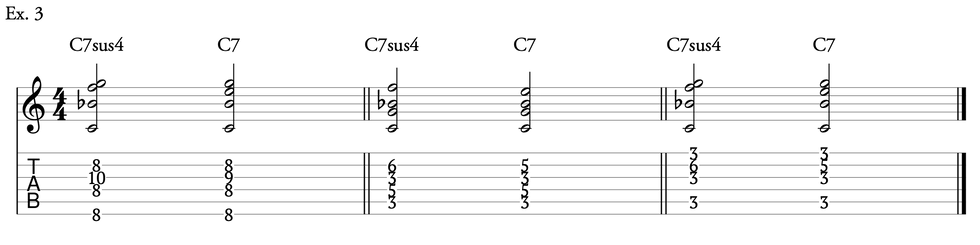

Another one of Sco's trademarks is picking close to the bridge to get a thin, piercing tone. You can hear this in Ex. 3. The second half of the lick features the A melodic minor (A–B–C–D–E–F#–G#) with some added chromatic passing notes, such as the F at the end of beat 2. The lick ends with a tangy major seventh interval.

Ex. 3

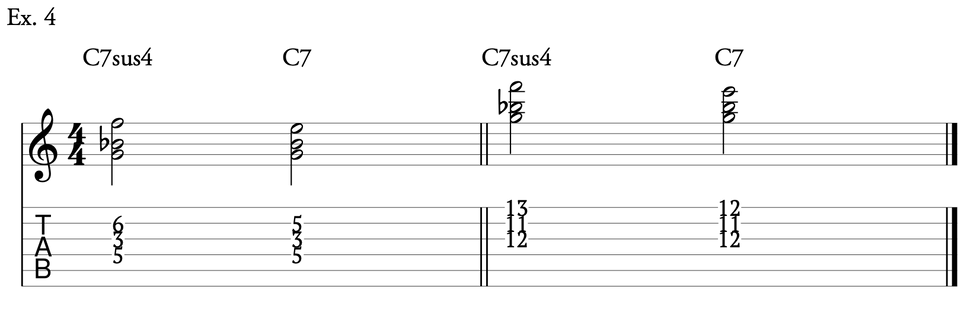

Ex. 4 gets a bit more liberal with outside notes, but rather than thinking of what scale these come from, it makes more sense to focus on how the ideas are related. After outlining a C augmented triad (C–E–G#) in the first measure, I use "enclosures" to target the root on beat 3. You can either use diatonic or chromatic neighbor tones to help outline the harmony. The rest of the line is centered around A Dorian (A–B–C–D–E–F#–G), but with an added b5 (Eb) for tension.

Ex. 4

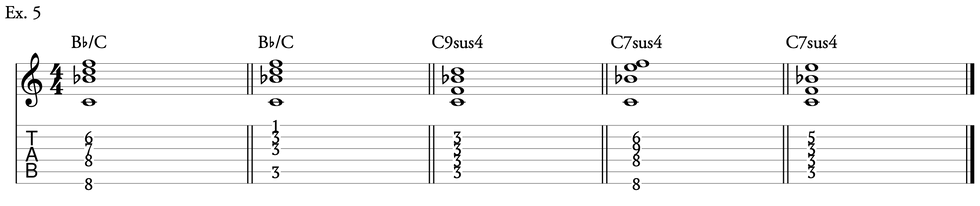

We use some blues-scale vocabulary to start off Ex. 5, but it soon shifts to bebop around beat 3 of the first measure, where the lines somewhat implies a Bm7b5–E7–Am7 progression. After a brief bit of blues vocabulary, we move into Super Locrian territory before resolving back to the blues scale. Ideas like this are not about outlining changes, but creating tension and resolution. When playing over a long Am7 vamp, a good way to add some interest is to imagine the V or a IIm–V7 change.

Ex. 5

Ex. 6 begins with an A Dorian line, but quickly transitions into something similar to the A half-whole diminished scale (A–Bb–C–C#–D#–E–F#–G). The diminished scale is a great way of adding a little bit of outside phrasing to a static vamp.

Ex. 6

Combining a stock pentatonic scale with a tension note (such as a 9) creates a classic Sco sound. In Ex. 7, we are doing just that. Over the first two measures we are using the A minor pentatonic (A–C–D–E–G) scale with an added 9 (B). After a brief sidestep up to Bb minor pentatonic, we resolve back to A Dorian. Note the use of A# and F#, which actually come from the idea of moving Em7 down chromatically.

Ex. 7

In Ex. 8 we do a fair amount of sidestepping. Again, it's more about creating tension and release rather than theoretically analyzing every note. Basically, look at positions. If you're in 5th position, it's mostly inside where 6th and 4th positions have their own outside flavor. Sliding between these areas will give you an obvious feeling of tension and resolution if they're separated, or all out chromatic madness if you're mixing both without any real periods of resolution.

Ex. 8

This article was updated on September 13, 2021

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)