A frequent Subversive Guitarist topic will be note choice—specifically, ways you can substitute relatively interesting notes for relatively conventional ones. Let’s start as close to the bottom of the musical scale as you can get: with the lowered second degree, variously called the flat second, flat 2 (b2), or lowered second. Dropping the second scale degree by a half-step can add color and character to your playing with relatively little effort.

What is b2?

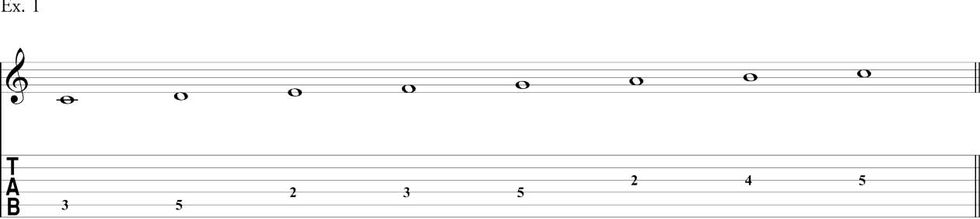

You probably know that the major and minor scales each have seven notes. There’s a whole-step (two-fret) gap between most of the scale steps. In major scales, half-steps fall between the third and fourth scale degrees and between the seventh and octave (a return to the first scale note, but eight scale steps above), as in Ex. 1.

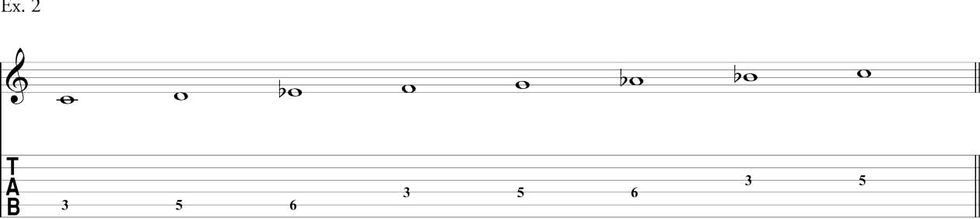

Minor scales are more variable, but most often the half-steps fall between the second and third scale degrees and between the fifth and sixth scale degrees (Ex. 2).

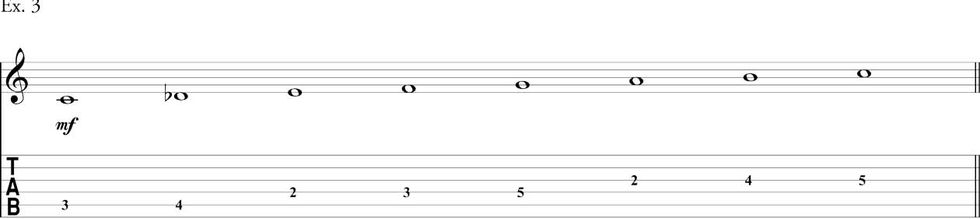

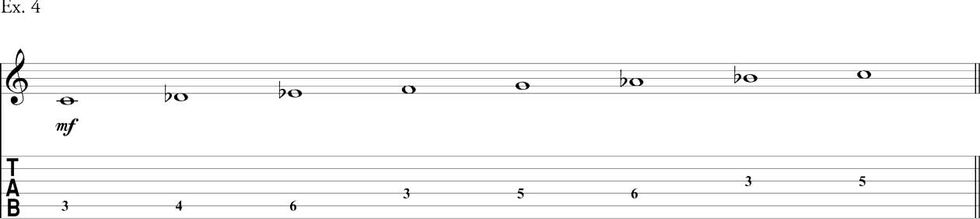

So, if we lower the second degrees of the major and minor scales, we get the mutant major (Ex. 3) and minor scales (Ex. 4) shown below.

This simple scale alteration has massive theoretical implications. But let’s put theory on the back burner for now and just use our damn ears.

What b2 Does

Anytime a half-step appears between two scale steps, it creates tension. It often feels as if there’s an invisible gravitational pull trying to draw the notes together. Consider the gap between the seventh degree and octave in the major scale: When you play a melody that should resolve on the root/octave, but doesn’t, you feel the tension. This simple “shave-and-a-haircut” tune is an obvious example. If you delay the arrival of the final note in the phrase, its absence is almost like a physical ache (Ex. 5).

Click here for Ex. 5

There’s similar tension around the half-step between the third and fourth degrees of the major scale. You can feel it if we add a couple of notes (Ex. 6). Here the seventh scale degree “wants” to pull up into the octave, while the fourth “wants” to resolve down to the third.

Click here for Ex. 6

Even though it lies outside the formal major scale, the b2 has a similar gravitational pull, as heard in Ex. 7. You can feel how the Db note pulls us toward the root. As before, it feels frustrating when you delay the final note.

Click here for Ex. 7

This chromatic scale degree can even join forces with the half-steps that occur naturally in the major scale (Ex. 8).

Click here for Ex. 8

It doesn’t matter whether you define that penultimate three-note chord as Db7, G7b5, or something else. It’s the half-step relationships that create the progression’s tension and release. We’ll delve deeper into the theory and applications behind this, but for now, here’s the key point: The b2 has the tension of a coiled spring—until it resolves, as expected, to the root.

The same “magnetic force” applies in minor keys. Check out the simple melody in Ex. 9. Here in the key of G minor, the second scale degree is A.

Click here for Ex. 9

In Ex. 10, however, we lower that A to Ab. It still makes harmonic sense, and you still feel the pull to resolve on G. It’s simply a darker, stranger way to get there.

Click here for Ex. 10

The Secret Blues Note?

Blues guitar playing (and all the rock styles derived from it) exploits the tension and release of one scale note resolving into another, often via string bending. Ex. 11, in the key of A, features the three most common bends: 4 to 5, b3 degree to 4, and b7 to the root. This sounds like pretty familiar stuff, right?

Click here for Ex. 11

Less familiar-sounding are bends involving the root and the b2. Obviously, this is less traditionally bluesy, but can you hear the similar tension and release? Can you imagine ways to exploit the unexpected dissonance heard in Ex. 12?

Click here for Ex. 12

Ex. 12 isn’t exactly traditional blues. But you often hear similar flavors in the playing of Jimmy Page, who’s fond of adding unexpected chromatic spice to his blues-based riffs. The b2 also figures in many metal riffs. In fact, it’s crucial to the initial riff from Metallica’s first hit, “Seek and Destroy,” a song that helped define the sound of modern metal.

Hop, Skip, and Jump

So far, our examples all feature the b2 resolving directly to the root. But can you leap to and from it? Can you use it in melodies that don’t resolve immediately to the root?

Just ask Henry Mancini. His first big hit, “The Theme from Peter Gunn,” gets much of its tension from the b2. Dig it!

This original version heard here is in F, whose b2 degree is Gb. This note doesn’t occur in the initial guitar riff, but it appears over and over in the horn melody superimposed on the riff. Those slightly sour lowered seconds make the tune sound suspenseful and dangerous.

Ex. 13 has a similar flavor, cleverly redesigned to sidestep copyright infringement. We’ve dropped down to the key of E (as many guitarists do when playing the Peter Gunn theme). Here the lowered 2nd degree is F natural. The note appears in passing in the initial riff, and then throughout the subsequent phrases. It’s not exactly subtle—I pound that frickin’ F natural into the ground! But it should help you learn to distinguish the sound. The two measures marked with the letter A show the backing riff, while the solo part starts at letter B.

Click here for Ex. 13

The backing track below is simply a looped version of the background riff, which you can use for your own experimental jamming.

Now that you’ve explored the basic concept, why not try applying the b2 to your own riffs and improvisations and see whether anything clicks? Try bending up a half-step from the root in bluesy contexts. Practice some scales with the second degree fingered a fret lower than usual. Experiment with using the b2 as a melodic variation, as in Ex. 8. Simply put the sound in your ears, and then see if it takes root in your imagination. And hey—if you come up with any cool riffs, chord progressions, or melodies featuring the b2, please share them! There are endless uses for this dark and distinctive dissonance.

Geeky Epilogue: What About the Modes?

Modes, schmodes. In my admittedly eccentric opinion, modes are a terrible tool for understanding and integrating non-diatonic tones. Among the reasons:

• The modal system originated 2,500 years ago in the age of Pythagoras and was codified into its “modern” form in the 10th century AD. Music of these eras was 100% monophonic. There was no concept of two or more simultaneous melodies, let alone chords as we understand them today. The modal system is simply not equipped to deal with modern harmony.

• There are only seven traditional modes, a miniscule percentage of the number of possible scales. There’s no great rationale for focusing on those seven traditional patterns other than the fact that they’re … traditional. Consider our topic, the b2 scale degree. Two modes feature this interval, Phrygian and Locrian. Both are minor modes—the modal system can’t account for a major scale with a b2, like the one in Ex. 1. Or a minor scale with a raised 4. Or with a raised 6. Or a raised 7. You get the idea.

• The Ionian mode corresponds to our major scale, and Aeolian to our natural minor scale. But beyond that, modern music is rarely strictly modal for more than a few bars at a time.

Most of us hear music as major or minor, with occasional chromatic coloration. I suppose you could describe Ex. 9 above as, “starts in Aeolian mode, but shifts to Phrygian at the end.” But doesn’t the following sound a lot more intuitive? “Ex. 9 includes a passing Ab because sometimes it sounds cool to lower the second scale degree in minor keys.”

My argument gets really boring, really fast—but that probably won’t stop me from making it. Just one disclaimer: If you’re currently a music student studying modal theory, please don’t bring my crackpot concepts to class. You’ll probably flunk, and then I’ll deny I said any of this.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)