Chops: Intermediate Theory: Beginner Lesson Overview: Understand how to improve your fingerstyle technique. • Learn how syncopations work in ragtime music. • Develop a deeper understanding of Joplin’s masterpiece, “The Entertainer.” Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation. |

One of my first galvanizing experiences as a beginner guitarist was when I found a YouTube video of Tommy Emmanuel, C.G.P, playing his Beatles medley. The mix included “Here Comes the Sun,” “When I’m 64,” “Day Tripper,” and “Lady Madonna,” all of which clearly utilized Scott Joplin-style syncopations. While half the comment section under the video seemed to use this face-melting performance as an excuse to burn their guitars in desperation, it looked like an opportunity to me. Even though I was almost totally ignorant as a guitarist at the time, I’d had a couple of years of piano lessons, and Joplin’s “The Entertainer” was my first ever recital piece. That simplified version of “The Entertainer” didn’t have the handfuls of octaves and parallel 10ths that Joplin wrote in the original score, but all the syncopations were exactly the same, and the central concept was understandable. That basic piano foundation meant that once I had a few chords under my belt as a guitarist, I took to fingerstyle guitar like a duck to water. Maybe I can help replicate that learning process in you.

Conventional guitar and piano teaching methods are worlds apart, but I believe the two instruments are more alike than they are different. I’d like to continue to bridge the gap between them by taking a fresh look at one of the most iconic pianists of the 1900s, Scott Joplin, and study how his music relates to guitar. In this lesson we will cover some of the signature styles in Joplin’s compositions, demystifying his syncopations, and providing useable fills to drive home the memorable fundamentals of ragtime.

This topic might be most useful if you’re looking to give your guitar playing more texture or greater presence, so that it sounds bigger than it is. Much of this can be accomplished through no-brainer techniques and some sleight of hand on the fretboard. Nearly every guitarist’s introduction to ragtime is through Joplin’s most famous composition, “The Entertainer,” shown below played by the great Chet Atkins.

Compare and Contrast

While guitar and piano share many properties, such as the ability to produce polyphonic music and generate

sympathetic overtones through string vibrations, there are still notable ways of expression that lend themselves

more to one instrument or the other. For instance, voice-like phrasing, intervallic ear training, the CAGED system,

and Nashville notation techniques may come easier to many guitarists than they would to pianists.

However, there are other areas in which pianists may have a leg up on guitarists, such as effortlessly being able to play add9, sus4, sus2, and similar chords with notes close together in the scale. Sight-reading is more clear-cut on piano because there are no duplicate notes anywhere on the keyboard, so there’s not as much of a guessing game about how to play certain chord shapes. The piano is more frequently treated as a solo instrument that can effortlessly accompany itself and provide its own call and response, and is often used as a compositional instrument by orchestral composers, whereas most of the time guitar compositions are written within the context of a full band and aren’t designed to project in the same way. This means that guitar pieces are usually more dependent on what other members of a band might be playing. This is neither good nor bad, just a different approach.

CAGED Inversions

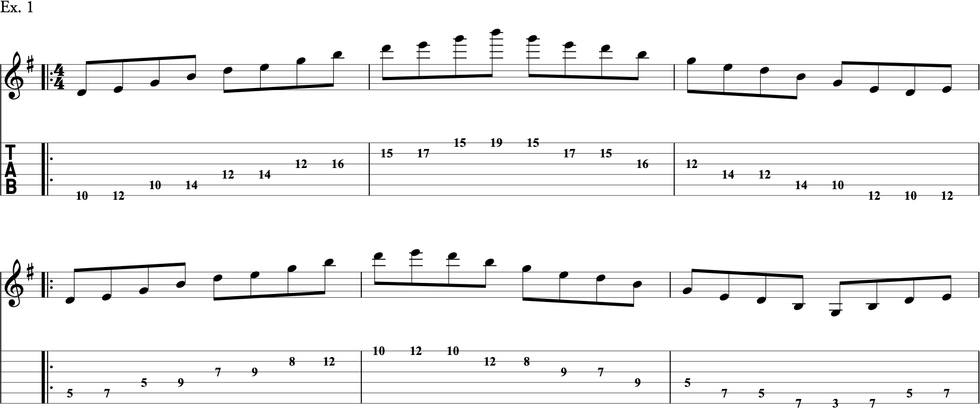

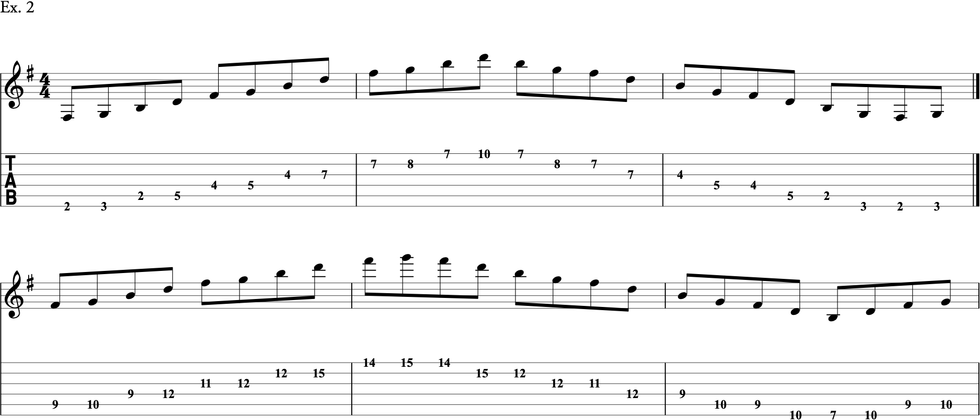

Ex. 1, Ex. 2, and Ex. 3 provide examples of the different CAGED

chord shape inversions. While these shapes may not be revolutionary on their own, knowing multiple inversions and

where they connect to each other allows you more flexibility as an arranger when you incorporate basslines. This way

of approaching chord shapes is called the CAGED system because each shape up the neck is based on a corresponding

open-position chord. (Check out “The Guitarist’s Guide to the CAGED System” for more info.) These shapes will be

invaluable as we dig into Joplin’s music.

Click here for Ex. 1

Click here for Ex. 2

Click here for Ex. 3

Open for Business

For Ex. 4 and Ex. 5 I’ve incorporated open strings into the chord inversions. This

creates a wider tonal range for you as a player. In some ways it’s hard to have the reach of a piano player while

playing the guitar but using open strings while playing chords up the neck is a great workaround for that.

Click here for Ex. 4

Click here for Ex. 5

Pedal Notes, Open Strings

Most pop and jazz writing styles rely on the circle of fifths for constructing chord progressions. Even in the

hairiest of songs, you’re likely to see I–IV–V or II–V–I root movements. Adding pedal notes to the basslines of

these commonly used chord progressions is a way of adding color to chords without necessarily changing the whole

harmonic value of the chord and allows us to add depth and intrigue. In Ex. 6 you can play through

a few examples of this.

Click here for Ex. 6

When chords with pedal notes are listed above the staff in piano notation, they are listed with the chord name first,

followed by a slashwith a note name listed later. For instance, a C/E would be a C chord with an E as the lowest

bass note; an F/G would be an F triad with a G added as the bass note. Harmonically, it could be considered an add2

chord, but the fact that the G would be played as the lowest note in the chord, even though it’s not the tonal

center of that chord, is what determines the chord name as an F/G rather than an Fsus2, Fadd9, or Fadd2. Those other

names aren’t necessarily wrong, but F/G gives more context.

Pedal notes don’t always change the overall type of chord, although sometimes they can. They’re not used so much as a form of blatant reharmonization, but as an indicator of where the chord progression is going next: musical foreshadowing, so to speak.

While the official Joplin sheet music is notated classically and doesn’t actually list the chord progression, quite often you’ll see the pedal notes stated in the bassline. This is trademark Joplin left-hand style, and it creates a sense of movement under the melody line and serves as an interesting, but stable, background for the right hand on the piano to be more adventurous.

Syncopations

Ex. 7 introduces common syncopations as they tend to show up in fingerstyle arrangements. These

syncopations are all done in isolation, over a basic E chord, rather than in the context of a chord progression. The

biggest thing to remember when trying to play syncopations is to tap your foot to keep time, and if you find

yourself getting lost, just hold up a pencil or straight edge vertically over the staff to help figure things out.

Notes show up in the staff as they happen, so if a note is to be played before another, it’s going to show up before

the next one.

For this exercise, the down-stemmed notes represent what your thumb should be doing, and the notes with the stems up represent what your other fingers will pick. If you’re having trouble figuring out where the notes fit together, try playing this with a metronome, alternating between playing really slowly and really quickly. This is one of the best ways to really understanding the timing. It may also be useful to count the time signature in eighth-notes instead of quarter-notes.

Click here for Ex. 7

Chord Changes

Ex. 8 is a much simpler syncopation pattern, but it incorporates a fill and a bassline. Pay

attention to the fingerings listed here, so that you are already in place to hit the next notes easily without much

moving around.

Click here for Ex. 8

The final two examples focus on incorporating a melody line over a bassline, with a rhythm fill in between.

Ex. 9 is an excerpt of the verse of “The Entertainer,” and Ex. 10 is from the final section of “Maple Leaf Rag.” Compared to the original songs, I’m not playing everything note for note, but I am trying to include the notes that stick out the most when I hear the original compositions.

Click here for Ex. 9

Click here for Ex. 10

When arranging for guitar, sometimes it’s unrealistic, or impractical, to try and copy a whole piece note for note, but you can focus on musical ideas that jump out at you at certain parts in the song, or you can at least try to incorporate the rhythmic texture, the right groove, and maybe some of the counterpoint that is most unique about that song into your interpretation of the song. These are some ways of misdirection that can create a convincing arrangement that still sounds full, even if you’re not technically playing every single part that was in the original song you’re arranging.

Below is a player piano recording of Scott Joplin playing “Maple Leaf Rag,” presumably in 1916, months prior to his death. This piano roll was accidentally found in an EBay sale, in a wrongly labeled piano roll box, and is one of the only alleged recordings of Joplin himself. I personally suspect that it’s really him, considering how comfortable and energetic the performer is with the piece. They’re playing the song with authority and they sound like they’re actually having fun with it. They don’t sound like the song is playing them, if that makes sense.

Performance Notes

Joplin supposedly only recorded six or seven performances for player piano before his death in 1917, just before the

neurological effects of syphilis robbed him of his ability to play entirely. Those piano rolls are the closest thing

we have of an actual audio recording of him. Some of the songs he recorded onto piano rolls were his arrangements of

other people’s compositions, but about half of the recordings were his own songs. He recorded “Maple Leaf Rag” twice

within the span of about two months, and the two recordings differ drastically in feel. One take is played with a

straight, moderate tempo, while the second is played at a similar speed, but with a dotted 16th-note swing to it,

and looser right-hand timing. The actual tempo these were performed at is debatable. Pianolas can play back a song

at varying speeds, and there is usually a suggested tempo printed on piano rolls, so there is some potential margin

for error with interpretation, but overall, the consensus is that Joplin’s tunes shouldn’t be rushed.

I’ve linked to what I think is the second recording of “Maple Leaf Rag” with a heavier swing feel to it, because I don’t hear people interpret this song in that way. It’s worth noting that both of his performances of “Maple Leaf Rag” include far more swing, more voice-leading detail, and more complex basslines and flourishes in the left hand than were notated into the officially published sheet music. These details were part of the composition rather than just improvisation. They show up consistently across both performances of the same piece. (I published a revised version of the piano sheet music myself, simply because I wish I would have had that as a younger piano student, and because it may be of value to anyone else studying this style in-depth. Go here to check it out.)