Is it good to able to read music fluently? Yup! (End of article.)

But it’s not quite that simple, is it? Learning to read well usually requires years of practice, and not everyone has that kind of spare time. If life obligations only let you play for a few minutes per day or a few hours per week, it’s probably not wise to over-invest in a reading regimen. Other factors include your preferred styles of music, whether you aspire to a musical career, and how much you value exposing yourself to a constant stream of new musical ideas.

This article’s goal is to help you arrive at your best decision. It’s a complicated calculus, with no hard-and-fast rules. Some might say reading is essential for professionals, but not for amateurs. Others might say it’s important for classical and jazz players, but not rock players. I find such views far too simplistic, so let’s attempt a more nuanced discussion. We’ll cover most of the usual considerations and some less commonly considered factors.

Readers and Non-Readers

I should disclose my background and biases. I learned to read as a little kid, and I kept reading through college and grad school. I can generally look at a piece of notation and “hear” what it sounds like, or hear music and visualize how it would look in notation. Sometimes I think I read music better than I read English. This reflects no innate talent on my part—it’s simply a matter of training.

But for all that, I’ve never insisted that all my students learn to read, and I don’t believe it’s a crucial skill for many guitarists. Most of my favorite players are non-readers, or semi-skilled readers who don’t use notation as a day-to-day tool. In some cases, a lack of theory and reading knowledge contributes to a player’s unique and exciting style.

Career Considerations

So who needs to read? If you’re going to pursue a degree in music, you need to read well. (You’ll probably need to learn piano too, so get cracking if you haven’t already.) This is probably true even if your specialization is rock, jazz, or pop.

Once upon a time, you had to be an ace reader to be a studio/session guitarist. That’s rarely true these days. The last time I had to do serious reading at a session was for a film score several years ago. If I’d been forced to decline every prospective gig that required reading, I’d have lost … maybe two percent of my work?

Composing for film or television was once unthinkable without notation skills. Even today few musicians would dare step into a big, expensive soundtrack recording session without strong reading skills. But increasingly, the music for film and TV (not to mention jingles) is produced independently in small studios, often by musicians without traditional training.

What if you dream of a career as a session player? Some of the leading Los Angeles players are superb readers, but a handful of players get most of the jobs. There are fine readers in Nashville, but guitarists are far likelier to use “Nashville number system” charts than standard notation. (The number system is a specialized type of chord chart.) In fact, you can make a case that “session guitarist” no longer exists as a career option. Most non-rock stars who make a living in music are multitasking: playing, performing, composing, recording, producing, mixing, teaching, and investing many hours in self-promo and social media. Sure, reading ability is an advantage, but it’s probably less of a factor than at any point in the past.

You don’t even need to read music to be a guitar magazine editor. I’ve edited for two major guitar mags, and in both cases, only a few of the editors were capable readers. (But obviously, you need those skills for, say, transcribing guitar solos or editing music for publication.)

Isn’t it possible to play MIDI notes into a DAW or notation program and have the program capture your performance in notation? Not quite. No matter how precise your performance or how clever your software, you must almost always make many manual edits before the notated music becomes suitable for sharing.

Tab: Fab or Drab?

These days far more guitarists rely on tab than on standard notation. Tab (short for tablature) isn’t some recent invention for guitarists too “lazy” to learn notation—fretted-instrument players have used tab for well over 400 years. Tab has helped millions of guitarists successfully learn millions of songs.

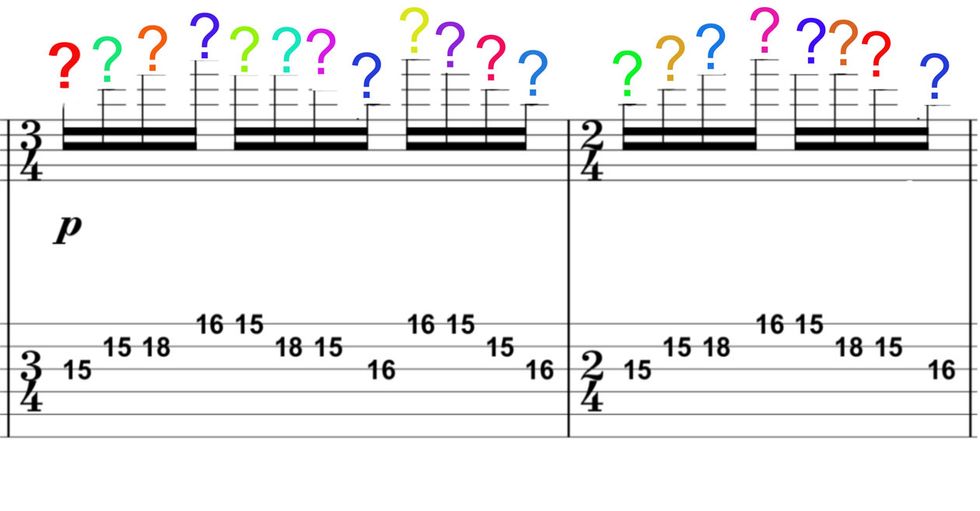

But tab has shortcomings. First, only guitarists can read it, so you can’t use it to share ideas with musicians who play other instruments. Also, tab conveys limited information about the music it depicts. As an example, consider the two measures shown in Ex. 1.

If you’re not a notation reader, try picking out the tab notes. Wow, a descending C major scale—big deal. Without the rhythms indicated in the notation, you might not realize that it’s the first phrase from “Joy to the World.” (The Christmas carol, not the Hoyt Axton song about Jeremiah the Bullfrog.) Tab doesn’t tell you how long to sustain notes, or whether to play them legato, staccato, or some other way. It communicates nothing about dynamics. It’s not clear when notes should bleed into each other and when they shouldn’t. And while tab can indicate note-to-note articulations such as hammer-ons, pull-offs, slides, and bends, it has no way to depict longer musical phrases.

Tab usually works great if you’re already familiar with the music you’re trying to learn. And that brings us to one of the strongest arguments in favor of music reading.

Learning What You Don’t Already Know

For me, the biggest benefit of reading well is the ability to learn from music you don’t already know. It’s a cliché to say that guitarists should study music by non-guitarists, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Tab can be great for learning a Van Halen solo, but it won’t help you learn a Miles Davis solo or a Bach prelude.

As an example, I often steal ideas from classical music for everything from rock solos to pop hooks. Racking my brain for an example, I thought of Igor Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, a piece for orchestra and chorus that I’ve loved since I was a teen but have never approached as a guitarist. I downloaded a free public-domain score and got to work.

For reference, here’s a fine performance of the score as the composer intended.

It opens with a chord so unique and renowned that classical musicians refer to it as (wait for it … ) “the Symphony of Psalms chord.” It’s a bizarre voicing of an E minor triad played by most of the orchestra. According to traditional music theory, the 3 of a triad is the note you’re least likely to double at the octave. But Stravinsky quadruples it, voicing the G in four different octaves.

With eight notes spread across more than three-and-a-half octaves, it’s unplayable on guitar. It’s literally impossible to play the three lowest notes on a single standard-tuned guitar. The chord is difficult on keyboard as well, though players with a good reach can handle it (see Image 1).

But if a single guitar can’t play the chord, can two guitars? To find out, I had to write down the chord, and then figure out how to divide the notes between two instruments (Ex. 2). Yes—it works! What a bizarre and fascinating voicing! But I’d never have known that if I couldn’t read music.

Click here for Ex. 2

Then I started thinking about other parts of the piece. In the opening section, the famous chord alternates with spiky, chromatic melodies employing half-diminished scales centered around Bb. Those are played by a bassoon and an oboe, doubling the melody at a distance of two octaves—a relatively rare voicing for guitarists. With its dissonant intervals and the tritone clash between the E minor chord and the Bb scales, this passage could inspire a hundred evil-sounding metal riffs. The odd-meter rhythms would suit any musical style with the word “progressive” in its name. And whoa—that two-octave doubling sounds an awful lot like impossibly fast artificial harmonics. I’m definitely going to be stealing that trick.

Those scales are a bitch to play at the indicated tempo of 92 bpm. I had to write everything down and learn the parts slowly from the page. This too would have been nearly impossible without reading skills. Ex. 3 shows the piece’s opening section, transcribed for two guitars.

Click here for Ex. 3

The goal isn’t to perform a symphony on two guitars (not that that’s a bad idea). It’s about stretching my hands into new formations and stretching my ears to incorporate these new discoveries. This cuts to the heart of the entire Subversive Guitarist series: breaking dead-end muscle-memory habits and finding new inspiration.

Another example: My previous column, on mutant folk fingerpicking, employed a simple concept: Take a pattern whose accent usually falls on the downbeat, and then shift the placement so that the accent falls anywhere but the downbeat. But there’s no way I could have gone straight from concept to performance. Again, I had to write it all down, and then practice from the page. It can be a laborious process, but if you’re lucky, it generates fresh, exciting ideas.

Obviously, That’s a Circle

For the sake of balance, here’s a final argument against relying too much on theory and notation. If you know theory well and have read lots of music from notation, you grow accustomed to the most common melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic formulas. That can be a valuable skill! But it can also make you leap to assumptions, ruling out less predictable, less theoretically “correct” options. It’s not a matter of guitarists with theory chops being sticklers for “the rules.” It’s simply that we sometimes assume prematurely where something is going, when the best destination might be someplace less predictable.

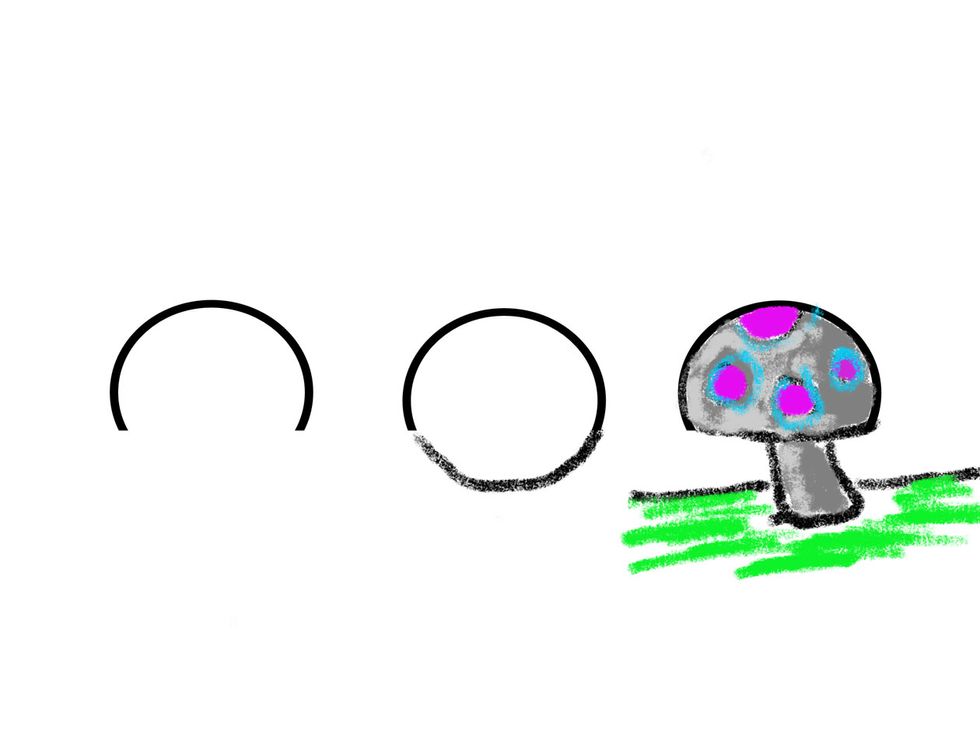

Here’s a visual metaphor: A player schooled in theory might look at the partial circle in Image 2, think, “Obviously, that’s going to be a circle,” and complete the idea as shown in the second drawing. But someone who doesn’t know the usual formulas might devise something more creative, like the third drawing.

Given the choice, I’d definitely choose “strong theory and reading skills” over “no theory and reading skills.” Yet I must admit that non-schooled players often devise the coolest, freshest ideas. Too often I make the expected choice because I know what musicians usually do. That’s the opposite of creativity! Maybe that’s why most of my favorite guitarists don’t have traditional theory and reading skills.

The Verdict

Hey, don’t ask me—the jury is you! I just hope I’ve presented a balanced perspective on an important and difficult decision for many ambitious guitarists.