Have you watched pole-vaulters on theOlympics?

I’ve always wondered what a lesson fora beginning pole-vaulter might look like.How do you practice something like thisslowly? I suppose you could travel to themoon where there is less gravity or maybepractice underwater where you could floatrather than suffer a nasty drop to the earthevery time you make a mistake. My guessis that budding pole-vaulters don’t doeither of those impractical things. Theyprobably just do a lot of falling and getbruised up more than the rest of us couldendure. My respect goes out to the pole-vaultersof the world.

Back to the world of guitar.

I’ve planted a vision of bruised pole-vaultersin your head to mentally prepareyou for something difficult and painfulon the guitar. But I’m going to do theopposite and give you something easy toplay. Breathe a sigh of relief and get readyto play ... two notes. Easy, right? Andyou can practice them slowly without anyworries of falling to the ground. I wantto make this into a rhythmic phrase, so Irepeated these notes a few times. The righthand will use alternate picking, starting with a downstroke.

I really want you to remember this phrase, so instead of using the generic title "Fig. 1,” let’s rename it Color TVs. It's an unusual name, but I’ll bet you won't forget it.

At this point, you may already be wonderingwhere this is leading. So I’ll tellyou. In this column, I’m going to show thebest thing I have ever played. What do Imean by that? I mean this is it. This is theSECRET. This opens so many locked doorsof technique and I’ve finally developed agood idea of how to explain it clearly.

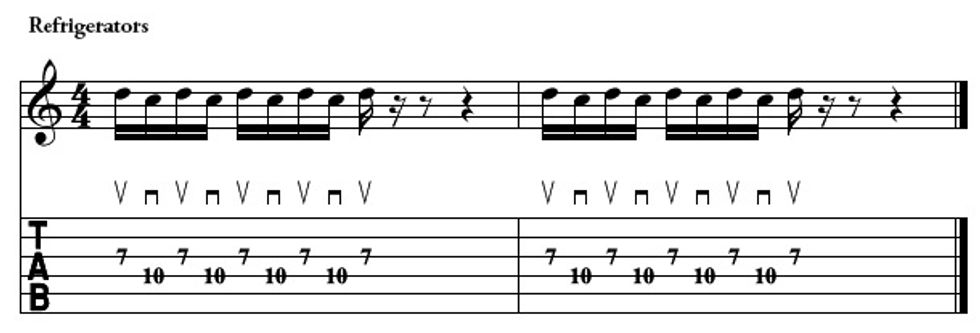

Let’s go to the next step. Do youremember the easy phrase that you playeda minute ago? Let’s play it again. Whileyou’re playing it, take a look at it, and askyourself one question: How many stringsare you using? This is not a trick question.The answer is one string. Now, I want toplay the same phrase using—brace yourself—two strings! I want you to rememberthis second phrase as well. So let’s get ridof the generic title “Fig. 2”, and call itRefrigerators instead.

It’s still just two notes. But since theyare on different strings, we now have somepicking decisions to make. We’ve cometo a crossroads. I’m going to suddenlytransform into a cruel, dogmatic, knuckle-rappingtaskmaster, and insist with a loudvoice that you must use outside picking.

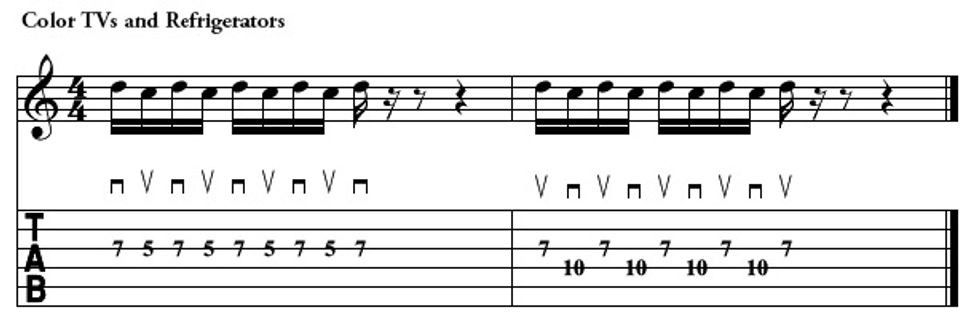

In this case, “outside” picking means thatthe first note—in this case, D—is alwaysplayed with an upstroke and the secondnote is always played with a downstroke.Your pick will never go in between (inside)the two strings. Instead your pick will stayoutside the strings, hence the term. Outsidepicking is better for these two notes.“Inside” picking is absolutely valuable, hasits place, and is better in many other situations.But please keep it away from thesetwo notes! Now let’s assemble a life-changingguitar exercise. We’ll put Color TVsand Refrigerators together.

Let’s stop right here for a second. Thisexercise is so important that I want to giveyou some advice on how to master it. Theloud-talking taskmaster returns and says:

• Notice that the Color TVs begin witha downstroke, while the Refrigeratorsbegin with an upstroke. The space inbetween will allow you time to getready for the change in picking.Hello! You’re back. Three weeks have passed,and you have digested the examples all theway back into the reptilian part of yourbrain. No barrier or distraction can stop youfrom playing it as easy as an E chord. Youcan play it on a guitar, with strings that aretoo high while plugged into an amp witha sound that you don’t like with a monitorwhere you can’t hear yourself, with a drummerwith erratic meter, a bass player who isout of tune, an audience that is asking formore Bee Gees tunes, and a dog that keepseating your homework. You don’t need tomake excuses. You can play it easily everytime. That’s what three weeks does. So now,you are ready for the secret. You still haveto move these Refrigerators. But you do nothave to move these Color TVs.

• Keep the tempo slow. The importantthings are: Use the correct picking strokesand keep the rhythm even and flowing.

• Respect the holes. Keep them intempo just like you would if theywere notes.

• Notice that every note is picked. Mymetaphor pays off here. “You’ve gotto move these refrigerators. You’ve gotto move these color TVs.”

• Practice. It takes 21 days for yourbrain to take a new physical motionand turn it into a motor skill. Howlong each day? I’d guess about 15 minutesa day, spread out in five-minutesessions. It’s such a simple lick, thatany more than that might get boringand that’s the last thing we want.

What am I talking about? Let’s look atour Color TVs for a second. It’s basicallytwo notes on one string. We’ve been pickingevery note. But we don’t have to! Thetaskmaster will still loudly demand thatyou pick the first note. But after that,the left hand can take over with pull-offsand hammer-ons. No more picking isrequired. You don’t have to move theseColor TVs.

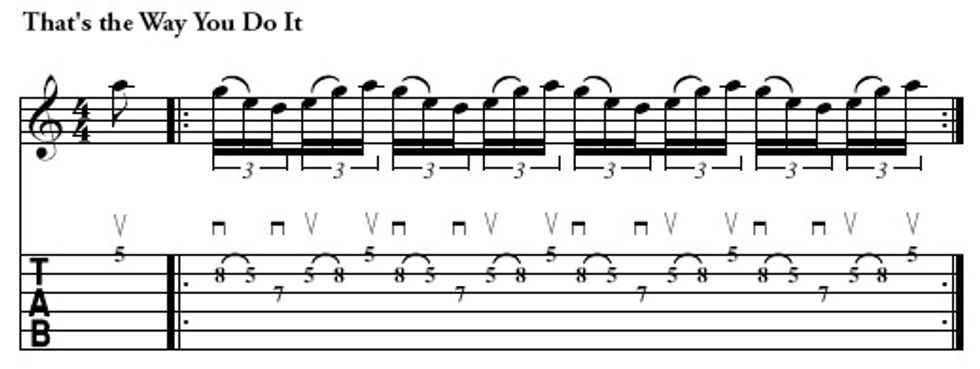

The Refrigerators still need to bemoved. But because you could take a breakfrom the Color TVs, you’ll be quickerand more powerful when you get to theRefrigerators. Here is a lick where thisconcept really pays off. Let’s call this oneThat’s the Way You Do It.

This lick is downright revolutionary.There are no Color TVs, onlyRefrigerators. And the result is that youcan play a phrase that uses three separatestrings with similar speed and ease as ifthey were on a single string. This solvespossibly the biggest technical challenge ofplaying scales and arpeggios on a guitar.

Now, before we invest three weeks in thisphrase, let’s ask an important moral question:Isn’t it morally superior to pick everynote? Aren’t we being lazy for making theleft hand deal with the Color TVs while theright hand takes a break? Doesn’t pickingsound better? Shouldn’t we practice pickingevery note to build better technique?

The answer is no. A hammer-on orpull-off has the same moral value as apicked note. Hammer-ons and pull-offssound great and in this case, they makethe difference between a lick being comfortableand playable, or being stiff andimpossible. You shouldn’t move theseColor TVs. It would mess up the lick.

Okay, the taskmaster is back. It’s timeto practice. Keep in mind that this lick hassix notes, a triplet feel, and should workwell over a shuffle groove. As always, startslow and make sure the picking strokes arecorrect. Don’t pick more often than youneed to. The biggest mistake students makewith this is they start moving the ColorTVs. You don’t have to. And the lick willfall apart if you do. Move the Refrigeratorsonly. I want that lick firmly embeddedin the part of your brain that acts out ofinstinct and habit. That takes three weeks.It’s well worth it to experience a revolution.

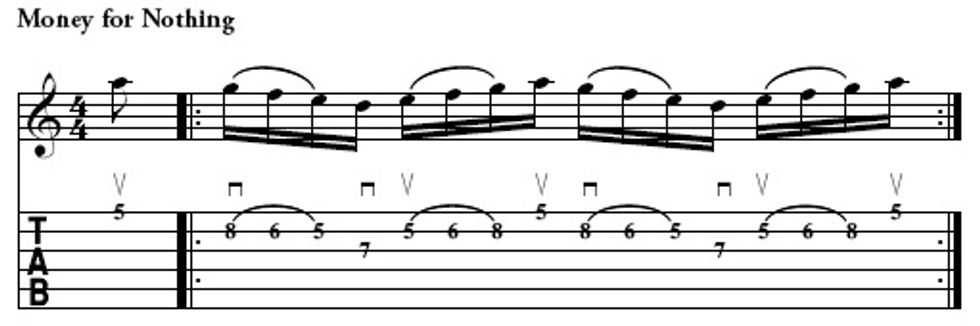

All right. You’re back again. There isno bad news. Only good. “That’s theWay You Do It” has so many applicationsand variations that I don’t know where tobegin. Or maybe I do. All we did here wasadd a couple of notes with our left hand.Our Refrigerators remain the same. You’vealready put in the practice for this pickingpattern, so there’s a good chance it willwork immediately. That’s why I’m goingto rename it, Money for Nothing.

At a medium tempo this will soundlike 16th-notes. But as it speeds up, I’vefound that the picking accents can makeit sound like 16th-note triplets. I reallylike how this fools the ear. It’s actuallyusing eight notes to sound like nine. It’salmost like someone smuggled in an extraColor TV. This will sound good over ashuffle groove, and could be written likethis next example.

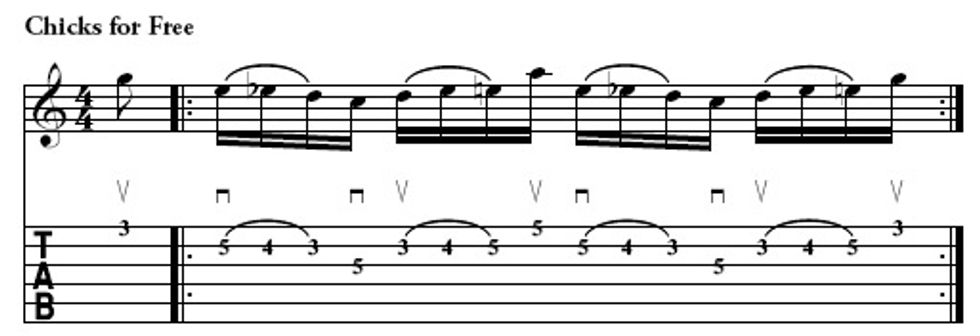

To give you a small taste of where youcan go with these techniques, I’ll give youtwo more variations. Both keep our pickingpattern the same, but use differentfingerings and note choices. The first usesnotes from the blues scale and a shapethat’s easy for the left hand. I’m too deepinto my metaphor now to call this one anythingbut, Chicks for Free.

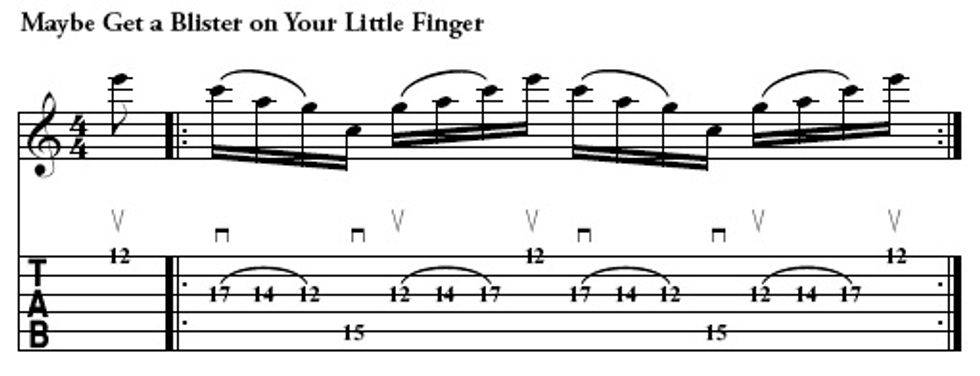

The next example, Maybe Get a Blisteron Your Little Finger, has a bigger left-handstretch and is a great way to play ablistering minor-7th arpeggio.

I have taught some of these phrasesbefore using clearly notated videos andtablature. But after watching students playthem, I realized that the exact picking patternis crucial to making these work. Inalmost every case, the problem was that thestudent was applying old picking habitsand trying to pick too many notes. Thisleft them tangled up and unsuccessful.The solution is to pick less. This requiresless motion and very specific coordination.When going from string to string, you’vegot to pick it. When playing more thanone note on the same string, you only haveto pick the first note and not the others.You’ve got to move those Refrigerators. Youdon’t have to move those Color TVs.

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitarat age 9, formed the guitar-driven bandsRacer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentallyhad a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching atGIT at the age of 18, has released countlessalbums and guitar instructional DVDs, andwill remembered as “the guy who got the drillstuck in his hair.” For more information, visitpaulgilbert.com

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitarat age 9, formed the guitar-driven bandsRacer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentallyhad a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching atGIT at the age of 18, has released countlessalbums and guitar instructional DVDs, andwill remembered as “the guy who got the drillstuck in his hair.” For more information, visitpaulgilbert.com