Mark Evans may not be a household name like his former AC/DC bandmates Angus and Malcolm Young, but nothing can take away his integral contributions to one of the biggest bands of all time. He took over bass chores from Malcolm in 1975, just after the band’s debut album, High Voltage, came out in their native Australia. Evans was 19 at the time, and with him in place Malcolm was freed to switch over to rhythm guitar, thus cementing one of rock’s most iconic and powerful guitar duos. From March of ’75 until the middle of ’77, he, Bon Scott, the Young brothers, and drummer Phil Rudd immortalized some of rock’s most timeless tunes—including “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Want to Rock ’n’ Roll),” “T.N.T.,” and “Let There Be Rock”—on the classic albums T.N.T., Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, the 1976 international version of High Voltage, and Let There Be Rock.

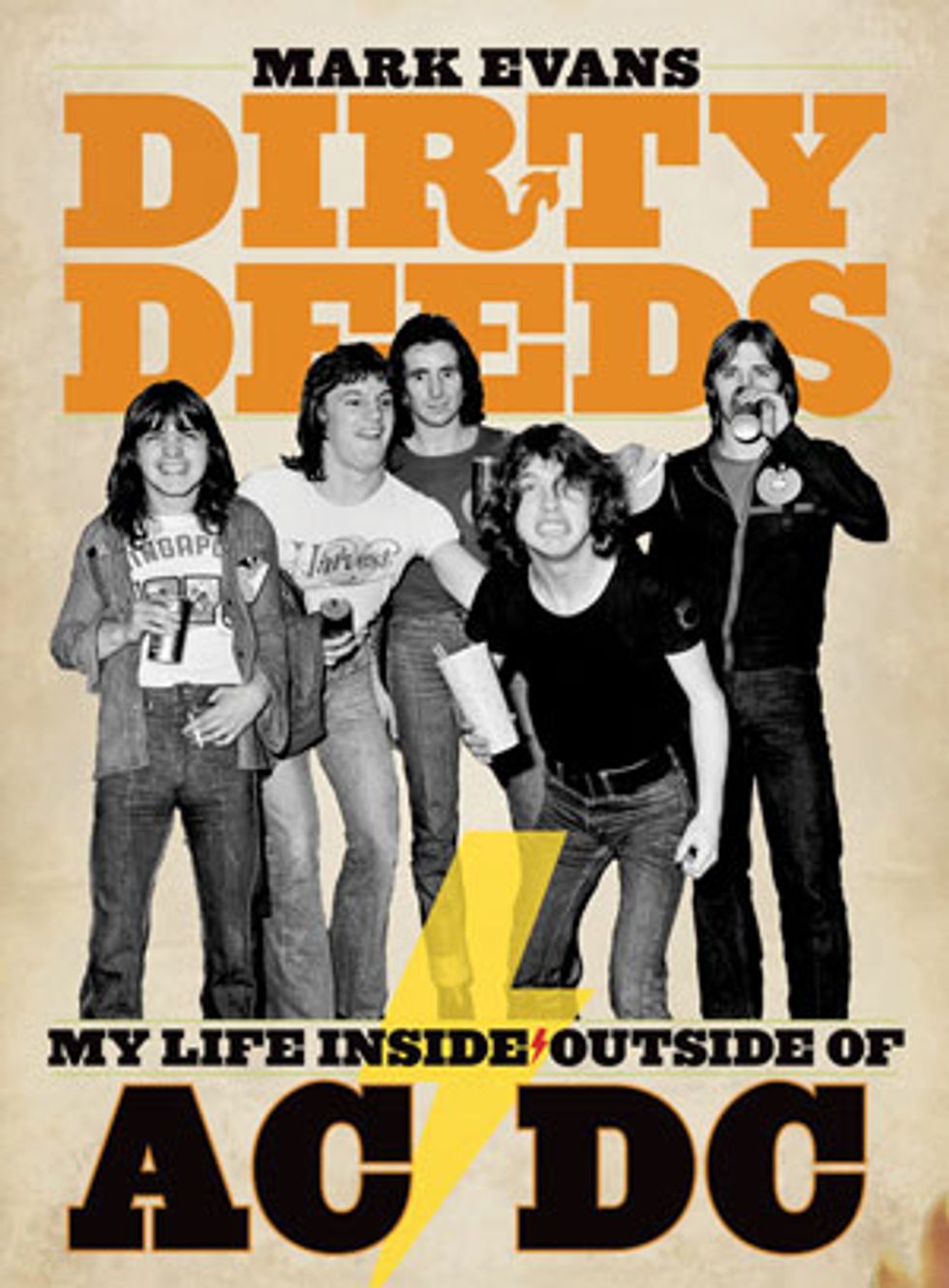

Evans’ new book Dirty Deeds: My Life Inside/ Outside AC/DC is the first insider account of the legendary Aussie band, and it chronicles the early years chock-full of wild times, triumphs, and tragedies. Recently released in North America, the book offers a glimpse at AC/DC’s studio approach and what it was like to ride the big black locomotive to superstardom in the 1970s. Premier Guitar recently spoke to Evans about the book, his gear, life on the road, and his relationships with the other members of AC/DC.

What did you know about AC/DC before your initial meeting

with members of the band?

Very little. I often went to a club called the Hard Rock Café that

eventually became the power base of the band, and it was owned

by AC/DC’s [then] manager, Michael Browning. I just happened

across a poster on the wall that said they were coming to town.

I’d heard bits and pieces about the band, but not much more

than there was a member that dressed up in a school suit. My

first real introduction to the band wasn’t until I received a copy

of High Voltage from them at their house, and was asked to learn

it for a jam session the following day.

What struck you most about that whole experience?

Probably that what they sounded like on that record was nothing

like what they sounded like live!

At what point did you know AC/DC was destined for big things?

That’s an easy question to answer: After learning High Voltage overnight,

I went back the next morning, we got the gear set up in the hallway

of the house, and the first song we tried together was called “Soul

Stripper.” The first thing Malcolm said was, “The first guy couldn’t

get this one together—that’s why you’re here.” He’s a very direct guy

[laughs]. We got started, and in the first 12 bars, when all the guitars

and drums started going off, this huge light bulb went off in my

head and I knew that this band was going to work. It was like in The

Wizard of Oz, when everything went from black-and-white to color.

Did you have any idea how huge you guys would get?

From very early on, I just knew AC/DC was going to be a contender.

We were prepared, we were good, and the opportunities

were coming our way. But with any situation like this, you need a

bit of luck.

What were your first impressions of Malcolm and Angus Young?

[That they were] cautious and very guarded … and somewhat

reserved. But the first thing that struck me about them was their

size. I’m not a big guy, at five and a half feet, but you look at the

old photos, and I look like I could be a linebacker next to them,

man! [Laughs.] I don’t think it would be overcalling the situation to

call them standoffish. It’s just the way they are, instinctively. It takes

a little while to break through the Youngs’ shell, but once you do,

they’re great guys. I think you just really have to make your bones

before they’re going to walk you into the crowd, you know?

You had known about Bon Scott and his other bands for some

time before meeting him, right?

Yes, and I was sort of impressed by Bon. When I was about 14 years

old, I went to a New Year’s Day gig at a club down the road from

where I was living. It was put on by a local radio station, and Bon’s

band, the Valentines, was one of many playing that day. It was really

something else, seeing Bon and six other guys dressed up in these

god-awful orange, see-through-chiffon tops and flares. Bon was a

backup singer, but I remember how taken aback I was with how

cheeky he was. I was sitting close to the side of the stage, where Bon

was neckin’ a bottle of Johnnie Walker in between songs and waving

and winking over at me. I was just a 14-year-old kid, but there was

something drawing me to him—he was such a character.

After that, I followed his career a bit, and he eventually ended up in a band called Fraternity. They were kind of the Australian version of Robbie Robertson and the Band. He was just a great guy—amazing onstage and very charismatic.

Left to right: Angus Young, Evans, and Malcolm Young tracking Dirty Deeds Done Dirt

Cheap at Albert Studio in Sydney, Australia, in January 1976. Photo by Philip Morris

Left to right: Angus Young, Evans, and Malcolm Young tracking Dirty Deeds Done Dirt

Cheap at Albert Studio in Sydney, Australia, in January 1976. Photo by Philip MorrisAnd yet, according to your book, you didn’t know Bon was in

AC/DC when you first tried out—and you didn’t meet him until

your first gig.

Yeah, that’s exactly right. Bon was always prepared to split from the

band and do his own thing, so he was often not around. When I

first met the other guys at the house, it was only Malcolm, Angus,

and Phil. They were talking about plans for the band and they

brought up the name Bon. I figured it could be the same guy, but I

didn’t want to push anything at that point.

Have you discussed the book with any current members of AC/DC?

No. We don’t have any real contact, and it’s a real shame, y’know?

We shared a period of history and did some really great stuff

together. It’s interesting you ask that question, though, because a lot

of people assume I would’ve had to clear the idea of the book with

the band. But no, there is no contact with the band. We all move in

very different circles these days. I would hope that somewhere along

the line the book gets through to Phil, Mal, and Angus, and that

they would read parts of it. I think it would refresh quite a few good

memories for them, because we had a great time on the road, man.

Judging from what you wrote, it sounds like you were closest

with Phil Rudd. Do you think that was mostly because you guys

were the rhythm section?

Phil and I were very close, but it went beyond our just being drummer

and bassist for the band. We’re both from Melbourne and are

both super keen on Australian football, even though we supported

different teams. But yeah, we were pretty close. You can’t spend

the best part of three years together, playing music and staying in

the same room, without knowing if you like someone or don’t like

someone. I’ve got to tell you what an amazing and great rock ’n’ roll

drummer he is—he’s just out of this world.

The book seems to imply that AC/DC was always Malcolm and

Angus’ band. Did you and Phil feel like you were full members

and equal partners?

I can only comment for myself on this but, from very early on, it

was very obviously Malcolm’s band. Malcolm got Angus involved

with the band, as well as their elder brother George, who was our

record producer. I always very much felt that Phil and I were members

of the band—there’s no question about that—but you also

came to realize, without it being stated, that Phil and myself didn’t

have any real input on the direction of the band or whatever the

band was going to be doing, business-wise. Bon may have had a

little more input than us, but he pretty much just went along with

the flow. Once we started going overseas, we were pretty much told,

“This is the deal, sign the contract,” y’know? But we were in the

band. We were all in AC/DC, not for our individual sakes, but for

the common good of the band. You did what was best for the band,

and you did it without question.

Left to right: Bon Scott, an unidentified “cop,” Malcolm Young, Phil

Rudd, Angus Young, AC/DC’s then-manager George Browning, and

Evans have a laugh and a drink during a March 1976 photo shoot for

“Jailbreak.” Photo by Philip Morris

Left to right: Bon Scott, an unidentified “cop,” Malcolm Young, Phil

Rudd, Angus Young, AC/DC’s then-manager George Browning, and

Evans have a laugh and a drink during a March 1976 photo shoot for

“Jailbreak.” Photo by Philip Morris

Bon was a bit older than the rest of the band—is that why he

often kept to himself and didn’t live in the AC/DC house?

The age gap was certainly quite noticeable. When you’re 19 and

working with someone who’s 29, that’s a big gap—especially

given Bon’s music experience and my being so green when I

joined the band. I also think Bon needed other things outside

the band to keep him happy. Being in that band, there was a

fairly rigid format and schedule, and with Bon being a bit of

a rebel, he could feel a bit suffocated. After a gig, if there was

something happening outside the band, he’d just pack a bag and

take off. There would be no “Hey, I’m going to a party. Do you

want to come?” He was always eager to put some space between

himself and the band, and he was the first to set up domestically

outside the band, too.

And the rest of the band actually lived together in a variety of

houses, right? Do you think that helped or hurt band chemistry?

I think it helped in the early days, since we had such a siege mentality—

we didn’t let people into our circle very easily. Initially, it

was a great thing, but once we got to England, Bon split pretty

early to live on his own. I’ve always looked back and wondered if I

should have done the same thing. It may have given me a bit more

longevity with the band, y’know?

The book kind of hints that most of the conflicts with the

brothers occurred when you all weren’t playing music.

You’ve got it exactly, man. When we were on the road gigging, AC/

DC’s work ethic was just amazing. There was never any gut-aching

about a particular gig—you just did it and had to be committed to

the nth degree. Sure, there would be some punches thrown on the

road, too, but that’s part of being in a band [laughs]. You just can’t

play at that level, in that type of band, and play that type of music

without getting fired up. But any issues we had on the road would

end the moment we stepped onstage.

It sounds like there wasn’t much time for the studio, given the

relentless gigging. What was the songwriting and recording process

like for all those classic albums?

Anytime we’d go in to record an album, our manager would basically

try to get as much time as our schedule would allow. The

three albums I worked on with the band—T.N.T., Dirty Deeds

Done Dirt Cheap, and Let There Be Rock—were each recorded in

less than two weeks. That was as much time as we could afford

to take off the road. So we’d go in the studio, where Angus and

Malcolm would knock together some guitar bits, but we wouldn’t

be presented with much more than a soundcheck where we’d mess

around with a couple of grooves.

All the songs would be written during the studio time—[back then] I didn’t even know about the concept of demo recordings. The first week, Malcolm, Angus, and George would get all the songs written, and then we’d go into a band situation to get the structure of the grooves right. So everything would be written and recorded in a period of a week—which is pretty mind numbing, when you think about how things are recorded today.

The second week would be all about vocals and guitar solos, which was the favorite part for Angus, of course. He’d love having a couple days in there to just do solos—and he’d be itching and scratching to get in there, man. The whole process really says a lot about how the three brothers worked together. To have a mentor and record producer like George Young, you’re blessed, and I was always a bit envious about their working relationship. You’d look at them working and think, “That’s a gang I want to be part of.” That said, there was certainly a wall around them, and it was apparent you weren’t going to get on that team, y’know? But George Young is a hero of mine, man. Great bass player, too.

Did you contribute your own bass lines, or did the Youngs

take care of that?

They used to work out all the parts on the piano, including the

bass. There would always be a grand piano in the recording room,

and the three Young brothers would sit alongside each other to

work the songs out. It was so funny, because they’re such tiny

guys. Seeing Malcolm in the middle, Angus on the right, and

George on the left, plunking away on the piano, was like something

from the Marx Brothers.

Evans and AC/DC playing the Nashville pub in London on June 3, 1976, during their first tour of the UK. Photo by Dick Barnatt

Evans and AC/DC playing the Nashville pub in London on June 3, 1976, during their first tour of the UK. Photo by Dick Barnatt

Wow—most of us would have never imagined AC/DC songs

being composed on piano!

It was a good way to get the bass parts going, and then the

chords. Phil and I would be around in the studio, so we would

definitely get the flavor of the songwriting beforehand. Phil

would get on the drums, Mal and Angus would grab their guitars,

and on the first album, yeah, George would show me some bass

parts. He really took me under his wing. That said, even with

the limitations imposed on the songwriting, it ended up being a

real plus for the band. Everything was written there and recorded

once, so there would be a real time capsule of what was going on

at the time. I think all the early recordings that I was a part of

were very honest. With the exception of the solos, they’re essentially

the band playing live in the studio.

In the studio, was Angus anything like what we’re used to

seeing onstage?

Not while we were recording the the backing tracks, but when he

went into solo mode, he’d be bouncing around the place, let me tell

you. It would be like asking Mick Jagger to stand still while singing

a Stones song. What a great guitar player, though. As far as solos

go, I don’t think he’s gotten the credit he deserves as a writer. I

think the two guys who construct solos better than anyone else are

Angus Young and David Gilmour. And Pink Floyd isn’t even my

cup of tea—I wouldn’t look over the back fence to see them. But

yeah, both those guys are amazing builders of solos.

You mention in the book that you bought your first bass

because no one else wanted to play bass. Did you start on guitar,

or was bass your first instrument?

Initially, I had the idea to play bass, and it was my first instrument.

Pretty early on, I caught on to the relationship with the guitar and

how they work together—not necessarily [with] the drums. I’ve

been playing guitar for many years, but I always come back to the

bass. I love the bass and will always be a bassist first. I just love the

sound and everything about it.

Let’s talk about gear. How much importance would say each

member of the band placed on their gear?

I think we all gravitated to what we liked and what felt good.

Malcolm and Angus found the instruments that were right for them

very early on. Malcolm’s sound was very dependent on his Gretsch

Jet Firebird, and in the case of Angus, he ended up playing that

Gibson SG Standard because he’s a tiny guy and the guitars are super

light. They are both super-smart guys, great guitarists, and were

heads-up enough to know which guitars’ sounds would click together

for the sound they were going for. And now, you can’t think of either

of those guys playing anything different. I get blown away when I go

to a gig and see people trying to play AC/DC songs with these big,

heavy-metal, high-gain guitar sounds—it’s just so wrong [laughs].

What was your go-to bass on those albums and tours?

Early on, I was playing Fender P basses. I had trashed one during

a gig the first month I was with AC/DC, and I went to a repair

shop to have some work done when I came across a cherry-burst

Gibson Ripper that I fell in love with. The moment I picked it up,

I thought it was such a cool bass. I went back to the Precisions for

a while, but I also used a couple of [Gibson] T-birds. Just like guitars,

basses are very instinctive things. If you pick one up and don’t

know in the first minute if it’s for you, it’s not for you.

You bought your first bass from a pawnshop for $22. What

kind of bass was it, and do you still own it?

[Laughs.] Oh, it was terrible, man. It was the world’s worst bass,

and it’s really amazing that I kept on playing. It was some generic,

P-bass-looking thing with no brand on it except for “Made in

Japan” on the back. And back then, that was a bad thing. I really

have no idea what happened to it—I think it got lost, and that’s

probably a good thing [laughs].

Evans, who’s now in the

vintage-guitar business, in

the garden of his Sydney

home with his Ripper and

a quartet of Gibson jumbo

acoustics: (clockwise from

top left) a ‘97 EC-30 Blues

King, a ‘75 J-200, an ‘02

J-200, and an ‘07 J-150.

Photo by Ginnie Evans

Evans, who’s now in the

vintage-guitar business, in

the garden of his Sydney

home with his Ripper and

a quartet of Gibson jumbo

acoustics: (clockwise from

top left) a ‘97 EC-30 Blues

King, a ‘75 J-200, an ‘02

J-200, and an ‘07 J-150.

Photo by Ginnie Evans

Bon Scott passed away a couple of years after your time in the

band—the same week that Highway to Hell went gold in the US.

Was his passing a complete surprise to you?

Not a surprise, but certainly a shock. You can’t lose someone like

that and not just be completely leveled by it. Given his lifestyle,

there were so many people who knew him who would say, “If Bon

went tomorrow, he really had a great time.” That certainly put him

in some risky situations, if you get my drift.

What did you think when Brian Johnson was brought aboard

so soon afterward?

I respect the way the guys handled it by getting right back to it. It

was pretty incredible. I don’t think there’s ever been a greater transition

between singers in an already successful band, ever.

It appeared that you would be included in AC/DC’s Rock and

Roll Hall of Fame induction in 2003. At the last minute, that

fell through. What happened?

I was actually kind of surprised when I first heard I was part of

the nomination. My initial reaction was to not accept the nomination,

knowing it would be a bit uncomfortable since we hadn’t

spoken in so long. The Hall of Fame, for whatever reason, chose

to review my nomination and decided I didn’t qualify. That’s

really it. I do think AC/DC should have been inducted much

earlier, but they certainly did it right by including Bon.

What was your most memorable show with AC/DC?

It was a homecoming, outdoor-amphitheater gig in Melbourne

when we first got back from London, and the reaction from the

crowd made us feel like we were the [expletive] Beatles. It was

really the start of something else for us, and we knew then that

there was a lot more work ahead of us.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.