Good Vibes

A hallmark of Ronson’s style is his unique vibrato, which could be so wide that at times it almost sounded more like a series of quick bends. But its quirkiness fit right in with the glam sensibility, and it always came across as musical. Ronson is possibly most well known for being a member of David Bowie’s backing band, the Spiders from Mars, and his outro solo in Bowie’s “Moonage Daydream” from the classic album Ziggy Stardust is a prime example of his unique vibrato.

Let’s look at Ex. 1, which puts the spotlight on a Ronson-style exaggerated vibrato coupled with bent notes. This can be a challenging technique, and the best way to execute it successfully is by starting with the traditional rock-style fretting-hand grip. With your fretting-hand thumb over the neck, rest the area between your thumb and index finger on the underside of the neck, creating a fulcrum point. Once you’ve bent the string, quickly rotate your wrist back and forth. Be sure not to push the string with your fingers, as this won’t provide as much strength and control as your wrist.

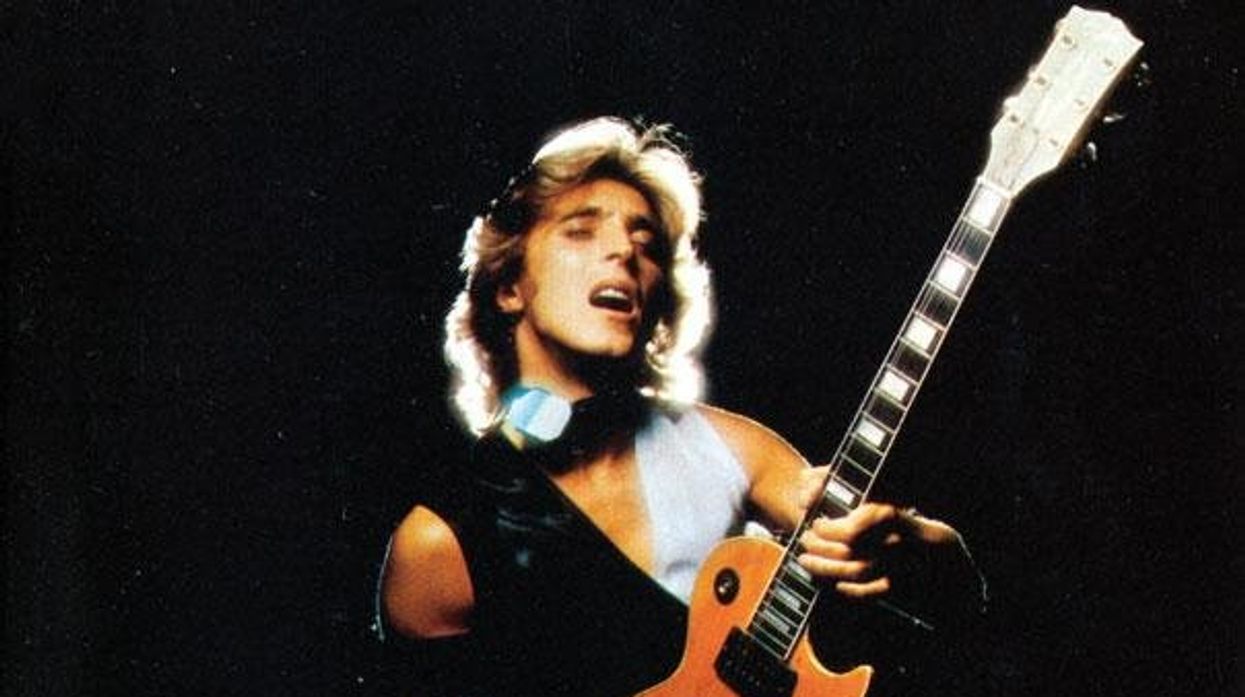

To fully emulate Ronson, be sure to bring swagger and confidence, like he always did. He brought a next-level intensity to Bowie’s shows, as evidenced by the following video. Witness the havoc he wreaks with his delay at 3:54.

Bending Melodies

Ronson had a particularly keen sense of melody and could create interesting melodic lines to fit over both simple and more complex chord progressions. A great example is his hypnotic guitar melody in Bowie’s “Suffragette City,” also from Ziggy Stardust.

To execute the entire melody, Ronson never once moves his fretting hand. He simply manipulates a single note by bending it varying degrees to fit over the chords. As far as technique, it’s best to use the same approach here as we did with vibrato, so as to have the most control over your bends. From a compositional standpoint, it can be helpful to be aware of the chord tones available, especially when dealing with a bit of an odd progression, like the one in Ex. 2. Here, the chord progression is: G (G–B–D), A (A–C#–E), G#m (G#–B–D#). We can think of this as IV–V–#IVm in the key of D (D–E–F#–G–A–B–C#) with the G#m chord being an odd, out-of-key choice. Looking at the chord tones, all are diatonic (in the key), with the exception of the G# and D# of the G#m chord.

Let’s take a look at two approaches to creating a melody similar to Ronson’s—one with not very much movement—over this sort of chord progression. First, when confronted with an out-of-key chord, such as our G#m, one approach is stress a note or notes which are out of key, as this can create an element of surprise. In measure three, the melody moves to D#, the fifth of G#m, which is out of key and works well here.

However, sometimes this approach can be jarring to the listener. The underlying chord is already out of key, and stressing one of the non-diatonic notes can prove to be a bit too much. In this case, a better choice is to find a note within the key which fits over the out-of-key chord. Now, this doesn’t have to be a chord tone, but here, the third of G#m (B), which is diatonic to our key of D can sound great, as demonstrated by this melody with almost no movement at all (Ex. 3). Note that for the G chord, the first note of the pair (B, the third) is a chord tone, whereas the second note (C#, the raised fourth) is not. It’s just the opposite for A chord: B is the second and C# is the third. After all, you don’t want to create cookie-cutter melodies, limiting yourself to chord tones alone. Always trust your ears and dare to try all sorts of options. But being aware of the chord tones can guide you through some tricky terrain.

Targeting the Third

In his work with Ian Hunter (Mott the Hoople), Ronson was sometimes called upon to dig into his bag of more traditional rock licks, but he always seemed to work his keen melodic sense into the mix as well. A great example is this live version of Hunter’s “Once Bitten, Twice Shy” from his 1975 self-titled debut solo album. Most rockers of the day would have leaned heavily on G minor pentatonic (G–Bb-C-D-F) over this common rock progression (C–G–D), but Ronson takes a different approach, mixing straight-up rock ’n’ roll with creative melody-making.

Ex. 4 takes a similar approach to the identical chords, starting with a classic Chuck Berry lick, then veering into more melodic territory by using the G major scale (G–A–B–C–D–E–F#). Stressing the thirds of the G and D chords (B and D, respectively) creates a sweet-sounding contrast to the more bombastic musical background.

Let’s try this “targeting thirds” approach with a different set of chords, as in Ex. 5. Here, we’re in the key of D, and over the chord progression D–F–G, we’re going to target the third of each chord — F#, A, and B, respectively. Stressing the third will often result in satisfying melodies, though doing it too much will have your listeners feeling as if they’ve eaten too much candy. Also, note how the F chord (bIII) functions as a non-diatonic bridge from the I chord (D) to the IV chord (G). Choosing to play its third (A) is another example of how stressing an in-key note over an out-of-key chord can yield smooth melodies.

Classical Gas

During his time with Bowie, Ronson could never quite be sure what musical setting he’d find himself in. “Time,” from Bowie’s 1973 release Aladdin Sane is a song with shades of Baroque music (think Bach), and in his solo, Ronson seamlessly adds lines that sound as if they could easily have been played by a classical trumpeter. First, enjoy David Bowie in his theatrically androgynous glory, as Ronson’s guitar emerges from behind his vocal. (Stay with it through the 4:00 mark!)

How does he accomplish this? He clearly draws from his classical music studies, but interestingly enough, it’s not about the notes as much as it stems from the rhythms he chooses. Ex. 6 showcases simple lines, all within the key of C (C–D–E–F–G–A–B), relying on mostly steady eighth- or 16th-note rhythms to lend a strict classical feel. As they often do, the details matter here: For example, notes with a dot above are to played staccato, or short. To accomplish this, after striking the note, quickly lift your finger so it rests on the string, thereby deadening it. Incorporating this sort of articulation and the quick 32nd-note flourish in measure one, along with rock-style vibrato and the sly bend in measure four creates a mix of modern and classical flair that Ronson could effortlessly summon.

Nothing Fancy Required

Aside from occasional use of delay, Ronson plugged his trusty 1968 Gibson Les Paul directly into various amps, most often a Marshall Major 200-watt head. Always with an eye toward detail, he had the finish stripped from his guitar, as he felt it gave the instrument more resonance. Armed with his vast musical experience and an equal ability to be subtle or unbridled, his playing remained unpredictable, as he loomed large over the glam rock scene. Let’s leave off with Ronson deftly weaving some melodic magic on the Bowie classic “Space Oddity,” of which the singer clearly approves.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.