Our world of guitars is peppered with cliches and theories about what physical attributes make an instrument special. I’ve always gravitated towards electric guitars whose sound not only blooms and holds on to a note or chord, but also leaps from your touch. This can be described as having great dynamic range and punchy transients as well as sustain. Whether we admit it or not, beyond the subjective matter of “good” tone, that’s the thing that we’re all looking for. You might describe it differently—such as calling it liveliness, or resonance, or something else, but it’s what makes a guitar seem “alive.” But how can you build that into a guitar?

Some point to the actual materials used in an instrument’s construction, others say the pickups do the heavy lifting needed to make this happen. I believe that it’s a combination of small details that conspire to either raise the game of a guitar or crush it into mediocrity. Here are a few things that I’ve found that need to be right in order to achieve the spunkiness that you seek—whether you’re building, assembling, or just modifying/accessorizing your guitar.

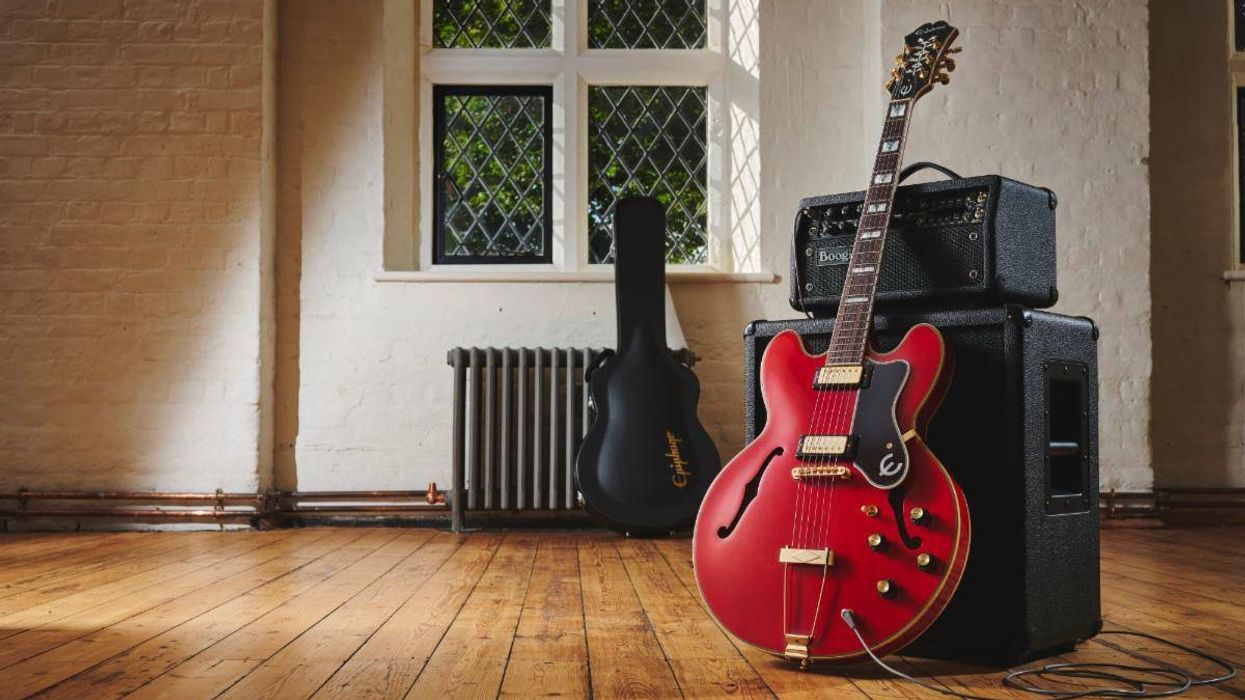

Builders like Tom Anderson and the late Rick Turner have endorsed the “unplugged test”—if the guitar is loud, balanced, and resonant acoustically, it will usually sound better when amplified. This is fine if you are starting from scratch, but how can you achieve this when you already have a finished guitar?

Get Tight

A snug, vibration-friendly neck pocket (or a carefully designed set neck) can make a guitar feel more like one piece of wood rather than two separate parts. Over the years, builders of bolt-on neck instruments like John Suhr and Grover Jackson have emphasized the neck joint fit itself because the way the neck and body vibrate together matters more than most players realize. I tend to agree. The more you can transfer resonance throughout the entire guitar, the more lively it will be. In a bolt-on guitar, you can remove finish within the joint and glue shim material to tighten the fit. This essentially puts wood to wood so that the entire instrument becomes one—and don’t forget to tighten those screws down tight. This is also a good time to check that the string alignment is correct relative to the edges of the fretboard, which helps playing feel. If you are building a set neck instrument, my opinion is that the larger and tighter the union is the better it will sound.

Mind the Nut

Most players think of the nut as little more than a spacer for strings, but it’s really an important gatekeeper of resonance. Sure, the slot depth and spacing matter, but a critical thing is how solidly that nut is bonded to the neck. If there’s glue slop under there, you’re leaking tone before the note even leaves the station. I always make sure the mating surfaces are smooth, flat, and fully seated—wood and nut material acting as one. When cutting slots, I file a gentle curve so the string leaves the nut as if it’s flowing downhill towards the tuners for maximum contact without snags. I stop my file exactly at the angle where the string will meet the tuner post—this way the string’s path is straight, clean, and free to slide.

“Sure, the slot depth and spacing matter, but a critical thing is how solidly that nut is bonded to the neck. If there’s glue slop under there, you’re leaking tone before the note even leaves the station.”

Batten Down the Hatches

No matter what kind of bridge you employ, make certain that all of the contact points—both to strings and body—have the maximum amount of contact. On wraparounds, Tune-o-matics, and Stoptails, be sure anchors are tightly set into the body. When installing them I always drill to the exact depth so the anchor presses firmly against the bottom of the hole. The name of the game is stability and vibration transfer.

Balance Tone, Not Output

I know there’s a lot of fine tuning that can be done with pickup to string distance, but the way I do it isn’t for volume balance as much as for tonal variety. On a guitar with two pickups, I always adjust by ear in the middle position, looking for a certain chime that I like. I’ve found that this position is often overlooked in favor of getting more gain from one pickup or the other, but if you get that middle sound right the rest usually takes care of itself, and your guitar will be more versatile as a result.

Because the way a guitar performs is a sum of all the parts, this way of looking at individual areas can eliminate potential weak links in your sound. In the search for a guitar that is alive in your hands and delivers a resonant sound, these small attentions are what can separate a dead plank from a singing instrument. Oh yeah—don’t forget to crank those tuning machines tight, too. That headstock does a lot more than host the logo.