A friend of mine, a true iron man of music—

engineer/musician/singer/songwriter/tech—has

a horrific secret: he's Beethoven-deaf. Currently

he works as a guitar tech for one of the most

famous guitarists in the world. I can't reveal

his identity because it could cost him his job if

his boss knew that his tech couldn't hear the

highs coming out of that stellar rig. Here's an

example of his staggering deafness: you know

that scene in the movie Poltergeist where the

little girl gives that prolonged scream after she

encounters the ghost? When my friend recently

watched that scene, he heard nothing; he literally

thought his TV had stopped working. He

got up off the couch and walked up to the TV

to investigate. When dialogue kicked in, he

discerned that the problem was his ears, not his

television. That is cochlear damage.

There are thousands of tiny hairs in the cochlea

that are stimulated by the pressure of sound

waves, like wind moving in a wheat field.

Different frequencies of sound stimulate specific

sections of these tiny auditory hairs, causing

them to move; this discharges electrical

impulses through the auditory nerve, which our

brains interpret as sound.

Here's the bad news: these tiny hair cells and

auditory nerves are easily damaged by either

a sudden loud sound (such as a feedback

spike), or an extended long period of time

exposed to loud sound (like regular gigging).

When these tiny hairs get bent or broken, they

send electrical impulses randomly to the brain

which are interpreted as sound, even though

there might be a complete absence of sound.

That's tinnitus, the ringing in your ears. I've

heard a theory that it is a little bit like phantom

limb syndrome—you know, an old soldier still

reaches down to itch a leg that was blown off

in Da Nang forty years ago. The line to the

receptor still exists, even though the original

receptor is gone (in this case the tiny auditory

hairs). These receptor lines are active and will

interpret any stimulus as sound. For example,

you squint your eyes just right, the damaged

receptor in your cochlea is stimulated, and you

suddenly hear a high B-flat note ringing loud

and clear. Cochlear damage is almost like a

faulty electrical connection.

A live stage punishes your ears, making

cochlear damage an occupational hazard.

The hell of it is that often it's not even your

amp that's robbing you of your precious

hearing. It's your drummer's bashing and the

occasional brain spike of painful feedback.

Even the warm lows of the bass that don't

feel painful are still laying waste to part of

your cochlea. Unless you're on a tour with

a killer in-ear monitor system and a quiet

stage, protecting your ears comes down to

wearing earplugs. Playing guitar and wearing

earplugs is the sonic equivalent of suiting

up with a couple condoms. Sure you lose

sensation, sure it feels unnatural,

sure it's not as fun—but

much like our Trojan friends,

these foam protectors should

be kept with you at all times.

Because earplugs color your tone by stealing

highs, you have to set your rig plug-free, really

playing with all of your settings: clean, dirty,

etc. Stand back as far as your cord will let you,

giving your ears the highs of the tonal spectrum

that your audience hears. Once your tone

is dialed, don't touch it, trusting that your rig

sounds like God Himself rocking.

The other day during sound check for the

Nashville Star Live tour, I set my rig sans plugs

on a big, open arena stage where you can

move some air. I cranked my ValveTrain amp up

to six and it really came alive—the kind of good

tone that almost makes you drunk. I cranked it

up to eight and I began hearing cool overtones

that aren't normally there. I was beginning to

feel a little giddy. I cranked it wide open and it

became sublime. Inspired, our drummer came

on stage and began pounding away, then our

bass player followed, and it turned into a Spinal

Tap jazz odyssey. I had more fun during the

trance-inducing ten minute jam than I had had

for the entire tour. We blew through sound

check with the singers and kept on jamming

until the stage manager ran us off so they could

open doors to let in the crowd. As I flipped my

amp to standby, a buzz in my left ear swelled

into a clear F# and I wondered if I would ever

hear that tone naturally in a mix again.

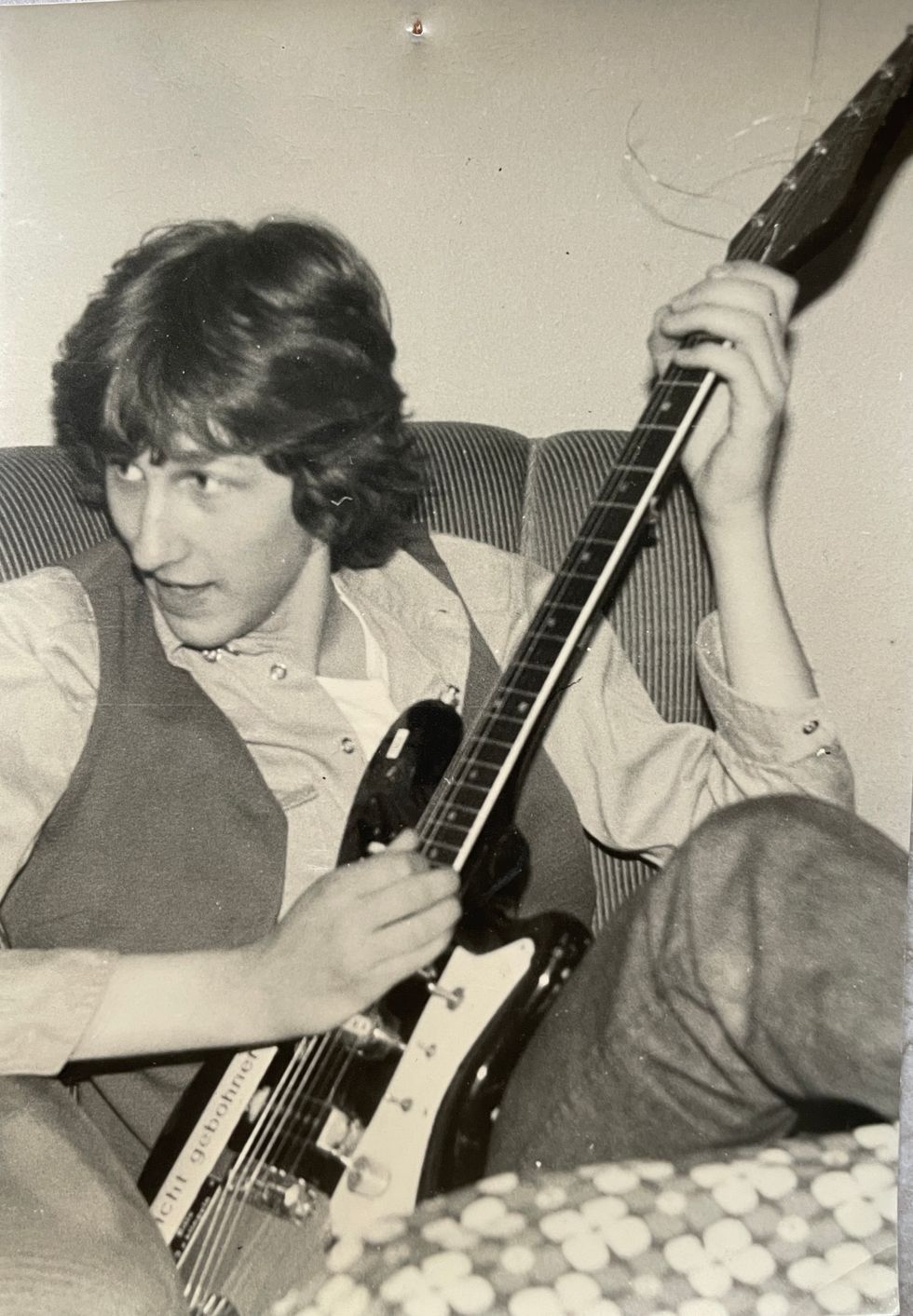

John Bohlinger is a Nashville guitar slinger who has

recorded and toured with over 30 major label artists. His

songs and playing can be heard in several major motion

pictures, major label releases and literally hundreds of

television drops. For more info visit johnbohlinger.com