I recently did a home-studio

project for an ESPN documentary

about Condredge

Holloway—who was both the

first black quarterback in an SEC

school and who led Tennessee to

three bowl games from 1972 to

'74. The show's producers needed

51 seconds of music that sounded

like classic '70s funk, and they

needed it fast. Licensing was not

available on the place-holding

music they were using, and

ESPN wanted to see (and hear)

something before the weekend.

I literally had two hours to get

something to them.

To think is to undermine:

Thinking makes the most natural

act unnatural. Think too much,

and you can't urinate in a public

restroom or sleep when you are

exhausted at 2 a.m. Next time

you're in a crowded room full of

strangers, really focus on walking

naturally from one end to the

other. You will inevitably feel awkward.

That's why booze remains

so popular at parties—it turns off

your brain so you can feel natural.

When it comes to getting a

natural feel while recording, I

hearken back to the words of my

mentor, Homer Simpson, who

said, in a nutshell: There's a time

to think and there's a time to do

stuff, and this is definitely not a

time to think. Because I spend

a good deal of my not-thinking

time watching music on YouTube,

I began this project by typing

“FUNK 1972" into YouTube's

search box and then mindlessly

engaging in “research" (I'm using

this somewhat academic term in

its broadest sense). I was lulled

into a semi-catatonic state as I

watched Earth, Wind & Fire,

Billy Preston, and P-Funk for

about 20 minutes, then I came

to in a panic thinking, “Get it

together, man. You've got a deadline—

do your work!"

Research temporarily concluded,

I created a new Pro Tools

session file, opened a Toontrack

instrument channel, and played

the first “funk" drum loop I

could find. It sounded sufficiently

funky, so I copied it onto instrument

track #1 and repeated the

two-bar phrase 100 times. Then

I imported the QuickTime video

version of the ESPN documentary

and saw the drums lock with

the vid. This took roughly seven

minutes. Next stop: bass.

Generally, I see bass as a white

canvas and guitar as the paint.

These minimalist leanings work

fine in country and dumb rock

but they do not apply to funk,

where the bass is right out front,

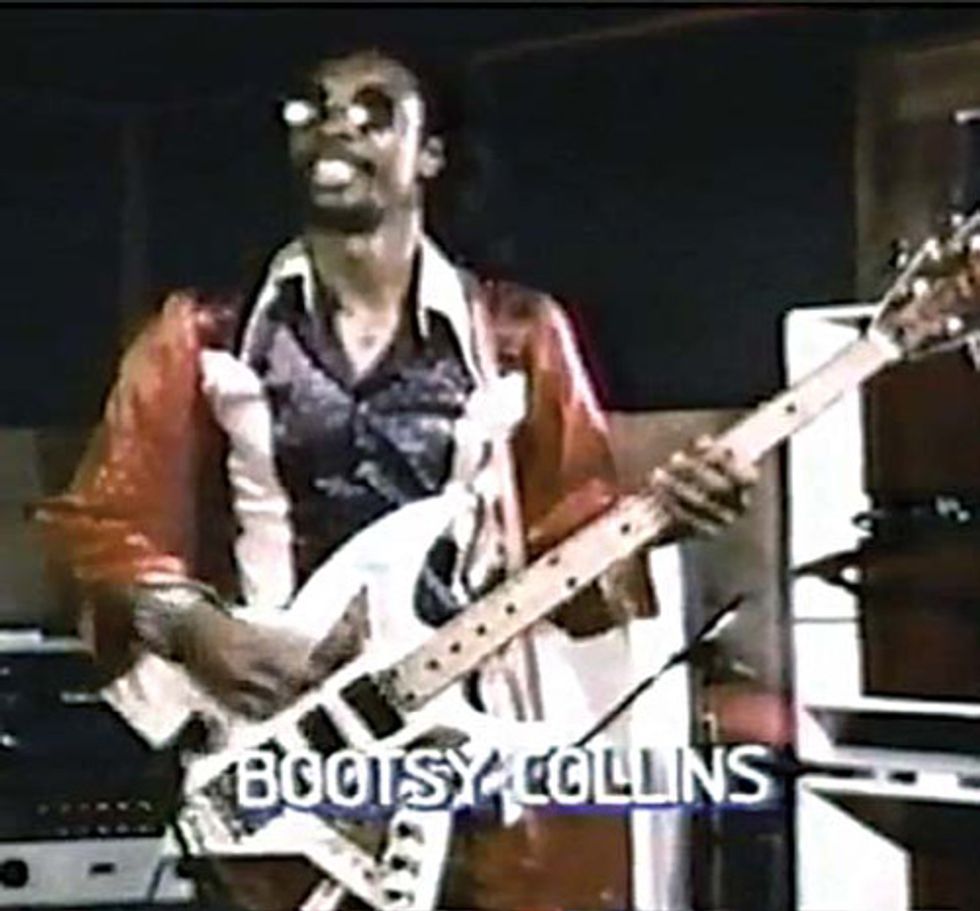

loud and proud. I went back

to YouTube, typed in “funk

bass" and found a video entitled

“Bootsy's Basic Funk Formula."

Search YouTube for “Bootsy's Basic Funk Formula," and you'll be rewarded

with a groovin' bass lesson from the “space bass"-wielding man himself.

Armed with one funk bass

lesson, I tuned up my bass,

plugged it into a DI box, and

played along with the drum

track, trying to shift phrases with

the scene changes on the video

screen. It took a few attempts,

but I came up with a pattern that

seemed to flow with the screen

images. After laying down the

bass, I listened to the track and

wrote down a quick numbers

chart, knowing I would inevitably

forget the chord changes.

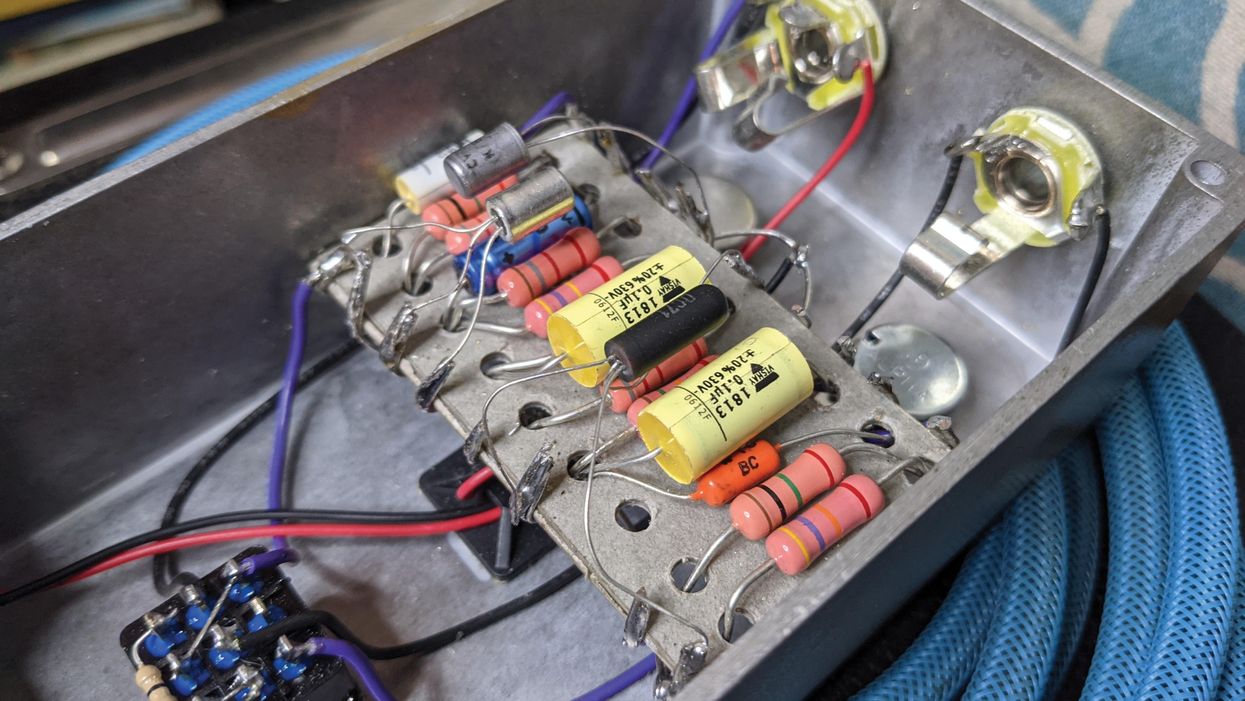

Having completed the hard

work for the project, it was time

for the fun part. I plugged my

20-year-old Cry Baby (which after

years of use and abuse is really

getting funky—in a bad way) into

my little Kustom amp. I chose the

Kustom because its blue-sparkle

tuck-and-roll covering looked

like something you'd see in a

'70s-era Commodores show. To

complete my '70s vibe, I used my

'75 Tele Deluxe (thanks Michael

McFarland, who traded me this

sweet brownie). I read the chart

down and played high triads with

a liberal dose of wah.

I opened up another track and

added a dirty lead part, sans wah.

It wasn't a great part, but I knew

that if I played it 20 more times,

it would be a little different, but

not really any better. Miles Davis

once said “Do not fear mistakes.

There are none." I hate to contradict

Miles, but there were some

honest-to-God wrong notes on

my track. I listened and removed

the few ugly parts and left the

space open rather than redoing

them. As Bootsy said in his video,

“Space is good."

In honor of Earth Wind &

Fire, I added a few keyboard-generated

horn stabs. Now the music

was sounding pretty close to what

the client had described. I added

some delay to the lead track,

compressed the overall mix, and

emailed it to the client. The entire

project, including lots of YouTube

visits, took under two hours.

The next morning I was

informed that the producers

didn't like the track, but they

got an extension and wanted

another version by the end of the

day—which gave me lots of time.

Rather than fix the old track, I

started a new track from scratch

and did the entire process over

again. Version two took a little

longer, because I put more time

into finding a cooler drum loop,

added drum fills at transition

points, and recorded an organ

pad over the entire thing. Overall,

it felt better. As of now, I haven't

heard back from the client, so I'm

going with that old chestnut: No

news is good news.

Deadlines are your friend!

Look at Guns N' Roses' Chinese

Democracy: $14 million, 17 obsessive

years, one crap record. I've

watched people rework a track

ad nauseam and manage to crush

any soul the music might have

had. Granted, there are exceptions

where over-thinking makes

amazing art. Rumours, Let It Be,

and Night at the Opera are notorious

for their obsessive excess, and

they are perfect albums. But for

those of us in the real world with

tiny budgets and limited time, we

just need to put our heads down

and crank it out with as little

thinking as possible.

a Nashville-based guitarist

who works primarily

in TV and has recorded

and toured with over 30

major-label artists. His songs

and playing can be heard

in major motion pictures, on major-label

releases, and in literally hundreds of television

drops. Visit him at youtube.com/user/johnbohlinger