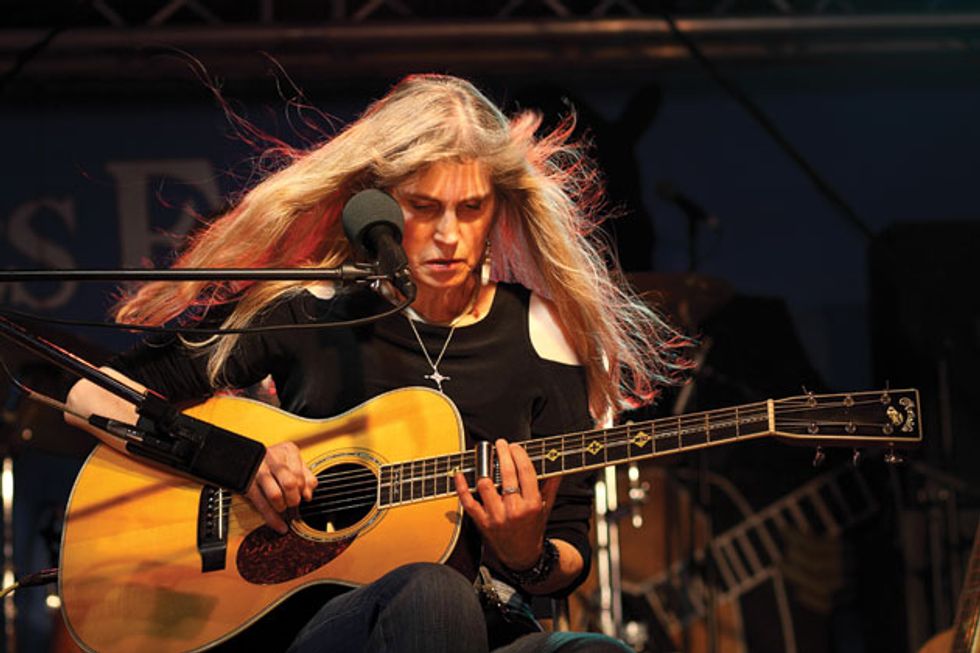

Rory Block plays acoustic guitar with the same intensity John Henry applied to driving railroad steel, and that has consequences. “Once, when I was on A Prairie Home Companion, the end of my finger was literally missing from playing ‘Crossroad Blues’ at the previous gig,” she recounts. “It was a humid night, and that can really peel your skin when you’re repeatedly pulling off the notes in a chord. I ended up folding a piece of tape over the end of my finger and smoothing it around the tip, so there were as few edges as possible. It wasn’t perfect in terms of the tone it produced, and it was slippery, but at least there was something between the open wound and the string.”

Block’s reputation for keeping nothing between herself and her music has made her one of the foremost interpreters of acoustic country blues for the past 30-plus years. Her recordings ring with commitment, starting with High Heeled Blues, Block’s 1981 solo acoustic debut for Rounder Records that met with raves from Rolling Stone, through her latest album, Hard Luck Child: A Tribute to Skip James.

It helps that no matter how much her signature Martin guitar takes a beating onstage as she pops, frails, plucks, and strikes its steel strings, every note and whinnying slide lick Block plays has the kind of bright, immaculate definition typically associated with champion flatpickers. That raw virtuosity and her soaring, wide-ranged voice has made her truly formidable. And those qualities are fortified by her songwriting skills.

Although country blues and primal gospel were Block’s first passions, she sought to establish herself as an original voice in R&B on her 1970s recordings for the now-defunct Chrysalis label. She met resistance, even from Chrysalis, and left the music business for a while under a cloud of dissatisfaction. When the skies cleared, Block began playing country blues again and signed with Rounder. But her foundation in fundamental American music has not made her predictable. Block’s full-band arrangements for 1986’s pop-inclined I’ve Got a Rock in My Sock, for example, defined the Americana-blues fusion sound a decade before Keb’ Mo’ parlayed it into a Grammy-winning career.

Block’s Martin OM-40 signature also has burly frets. “When you play slide and you use the second or fourth fret often for the capo, it really does a number on the frets—if you pound it like I do,” she says. Photo by Shonna Valeska.

For the past eight years, Block has once again been zeroing in on her roots with a run of tribute recordings to early blues masters. She began her self-described “Mentor Series” with 2008’s Blues Walkin’ Like a Man: A Tribute to Son House. Then came 2011’s Shake ’Em on Down: A Tribute to Mississippi Fred McDowell, 2012’s I Belong to the Band: A Tribute to Rev. Gary Davis, and 2013’s Avalon: A Tribute to Mississippi John Hurt.

Although the repertoire for these albums is plucked from the historic catalogs of the artists they enshrine, Block has kicked the three latest sets off with an original song about its subject. Hard Luck Child: A Tribute to Skip James begins with her impressionistic biography “Nehemiah James,” invoking God, the perils of sharecropping and levy construction, and the other trials of the ghost-whispering, singer-guitarist-piano player who was born in Bentonia, Mississippi, and enjoyed a career renaissance during the ’60s blues boom.

That’s when Block, who turned 65 on November 6, was growing up in New York City’s then-bohemian enclave Greenwich Village. Her parents were steeped in the Village’s nascent folk scene, and when Block fell in with the circle of musicians who performed on Sunday afternoons in Washington Square Park—which included roots notables John Sebastian, Stefan Grossman, David Grisman, and Maria Muldaur—her path opened. Block has pursued it with heart and determination ever since, leading right up to Hard Luck Child.

A hard-attacking player, Block says she often bruises her picking-hand wrist. Photo by Jason Ward.

You’ve just released the fifth entry in your ambitious “Mentor Series.” What inspired these recordings and how many more are you planning?

When I was doing my Robert Johnson tribute, it sparked a feeling that I might want to continue doing tributes, but maybe the theme should be tributes to blues masters that I’d met. I decided that since Son House inspired Robert Johnson, and I did meet Son House, he should be the next person I’d do a tribute to. Right away the “Mentor Series” name seemed obvious. Then, Fred McDowell felt like the next choice. I spent time around him when I was in Berkeley, when I was 15, and he stayed at the house where we were staying.

These albums seem like natural transitions. Reverend Gary Davis lived a subway ride away in the Bronx when I lived in New York City. We spent a fairly good amount of time with him at his house and in the apartment Stefan Grossman and I had on the Lower East Side in 1965. He was a huge influence. Mississippi John Hurt … I’d seen him onstage and met him in various venues, but we went to his house, too. Then I felt I should include Skip James. We saw him from time to time, but I really remember being in the hospital with him when he was declining, and that was very moving. I did meet Bukka White, but I didn’t actually interact with him, so I thought I’d feel complete with these five. I’m thinking in about a year from now we will release a boxed set of these albums. This really feels like the completion of an important cycle for me.

Do you think there’s a greater need for this music now? There’s a new generation of listeners who seem to be seeking a kind of authenticity and honesty that’s hard to find in today’s culture.

It’s very important for people to know about the source, so I’ve been motivated by that all along. But my number one motivation is that I love this music so much. I’ve been drawn to it from the age of 14, and since I started performing it was very important to me to say the names of the original writers of the songs I played. A lot of performers weren’t doing that. It’s important to say songwriters’ names so they get credit and listeners are encouraged to find out more about them. Moreover, royalties don’t grow and benefit the estates of these artists’ families if performers don't ever say their names and give them credit. That has changed, and I like to think I had a tiny part in that.

Most foundational blues artists used open tunings. I associate Skip James primarily with open G and D, but what tunings did you use for Hard Luck Child?

I play everything by ear and do whatever sounds right to me. Skip James did play some in open G (D–G–D–G–B–D), but I think more of open D (D–A–D–F#–A–D). Some people might tune, for Skip’s music, to a modal version of open D, but I was able to do what I needed to do in regular open D, which does not mean that he did it without making it modal.

Rory Block's Gear

Guitars

Martin OM-40 Rory Block Signature Edition

Amps

None

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

Martin acoustic SPs (.013-.056)

14 mm deep-well socket (for slide)

Open D was a popular tuning. Son House played “Preaching the Blues” in open D, and Robert Johnson played in open D. With Robert Johnson, my versions are as bare and accurate as I was able to make them. I didn’t want any layers. With Fred McDowell it got more modern, with layered guitars. He was more modern. And with Rev. Gary Davis, I really needed to do it as all-out gospel. The more all-out gospel I got, the more layers developed because I had to sing all the vocals—up to eight vocals in the background. And then with Mississippi John Hurt, although I know he didn't really play slide, at that point in the series the slide door opened up. That’s the way this series evolved. It all felt natural.

What about country blues captivated you at such a young age?

It’s an incredibly personal matter. I say to people, “It’s kind of like describing what made you fall in love with another person.” Chances are you can’t. But when I heard blues, my heart opened and I thought, “This is the most beautiful music I’ve ever heard in my life.”

Do you remember the songs that made you feel that way?

Not really. My parents had early Muddy Waters records in the house, so maybe that. I do remember the first blues record that Stefan Grossman handed me in 1964. It was Really! The Country Blues and it was snippets of lots of different artists, which was frustrating, because as soon as I was loving a song it would fade. It was sound bites, really. The idea was that it drove you to find the original. And it did drive me, because I thought, “Wow, this is the greatest stuff I ever heard!”

Because of the music my parents loved and played at home, my earliest influences were classical, folk, and early American blues and old timey music. From there, it was all the rediscovered vintage blues records that people were finding. They’d be put onto reel-to-reel tape and I would listen all night long, falling to sleep with headphones on.

Block designed her signature Martin model guitar with Dick Boak. It features a mother-of-pearl highway design on the fretboard that represents the journey of blues. The headstock bears a 1930s Hudson Terraplane, in homage to

Robert Johnson’s “Terraplane Blues.” Photo by Sergio Kurhajec.

How did you develop your aggressive, bare-fingered picking style, with the hard-driving thumb?

I started out with my bare hands, but with country music being the first guitar style I learned, I moved to the flatpick, pursuing the Carter family style. When I met Stefan Grossman, he was using fingerpicks, so I began using those. As soon as I started doing Robert Johnson songs, fingerpicks were out. The Robert Johnson style is like flamenco. If you’re going to strum down and roll all your fingers open against the strings and you have fingerpicks on, they are going to catch on the strings. So I took them off and immediately realized, “This is the sound I want.”

Of course, it makes your hands vulnerable. Many times my hands have been in agony and blood on the guitar. There’s really severe impact on your hands if you are doing it night after night, but as soon as you stop playing for a week your calluses start to soften up and then you have to rebuild them at great peril, when you play hard like I do. I have bruises on my wrist at the end of the night. I’ve tried to engineer the direction of my hand that comes down on the guitar to minimize the pounding that goes directly onto my wrist. I had to learn how to ease up just a little bit.

Let’s talk about your signature Martin guitar, which has interesting appointments on the neck.

Dick Boak from Martin Guitar and my husband Rob Davis [who is also Block’s live engineer and producer] and I went to a restaurant and started drawing our design ideas on a napkin. We came up with the neck as a nice blacktop highway that represents the journey of blues. There is a yield sign, a railroad crossing, a no-passing zone sign … a traffic light. Then Dick thought of an old-fashioned looking car for the headstock that resembles a Hudson Terraplane. I decided on a body size that was a smaller frame—a guitar that fits pretty much everybody. That was important to me. We did heavier bracing, a wider neck, and stronger frets, because when you play slide and you use the second or fourth fret often for the capo, it really does a number on the frets—if you pound it like I do.

How did you develop your ferocious slide technique?

For many years I couldn’t find a slide that really fit my fingers. You know, in the ’20s and ’30s nobody manufactured guitar slides. You used a jackknife or broke off a bottleneck, or, in Fred McDowell’s case, a beef bone. When slides did finally come to guitar shops, they were made to go over the entire finger of a man’s hand. People would bring custom-made slides to my shows—glass, blown glass, beautiful porcelain slides. But nothing quite felt right for me until John Hammond, Jr. said, “Go out and get yourself a socket wrench. They come in all sizes.”

YouTube It

Rory Block’s forceful fingerpicking is immediately evident in this live performance. She starts off using her socket wrench slide on a rendition of Son House’s “Preachin’ Blues” and then goes into a Robert Johnson tune.

I went to a gas station and I tried on all the socket wrenches, and found one that I liked. I didn’t want it to cover my whole finger because that wasn’t the style I’d become familiar with working with Fred McDowell. When I was sitting right next to him, he had this little piece of metal on the end of his third finger. So I thought, “That’s the way you should play slide—you should bend at the knuckle.” And that’s the way I play with my sockets.

It took me forever to really get a feel for it. That happened when Bonnie Raitt played on one of my records. [On the track “Rambling On My Mind,” for 1998’s Confessions of a Blues Singer]. We soloed her in the speakers and I went, “Oh! I’m doing it all wrong!” She has this incredibly relaxed style that goes up the neck in a laid-back way, and it was so funky and great. Then she would get to the fret she wanted and would rock around with this fabulous vibrato. It wasn’t tight and edgy, the way I was trying to do it. Bonnie’s playing informed me how to move forward, and I started practicing.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)