DIY may be commonplace for most bands today, but it was a downright revolutionary concept back in the late ’70s. That’s when punk bands who couldn’t land a record deal, get press, tour, book local gigs, or get on the radio pretty much wrote the DIY playbook. Their approach went on to develop into a massive movement and spawn multiple scenes—including the indie-, alternative-, and college-rock scenes—and its bands inspired everyone from the most intense thrash artists to sensitive singer-songwriters.

One of the earliest DIY punk bands, an influential trio that was do-it-yourself in every sense of the term, was the Minutemen from San Pedro, California. If anything, they personified the movement in how they embodied its proletarian ethos and values. They were determined, idealistic, and a prime example of great music that the industry missed or ignored.

But the Minutemen—Dennes Dale Boon on guitar (known as D. Boon, in homage to his hero, E. Bloom—Eric Bloom from Blue Öyster Cult), Mike Watt on bass, and George Hurley on drums—sounded nothing like their contemporaries. They didn’t play hardcore. They flirted with genres anathema to most punks, including classic rock, Motown, and post-bebop jazz. They knew how to play their instruments, too, and boasted formidable chops, impeccable time, and wide-open ears.

Although the Minutemen were very much a group effort, it was Boon’s guitar playing that stood out as the band’s most idiosyncratic element. Boon almost never played power chords or used distortion. His tone was abrasive, his comping—a hyperactive synthesis of’ ’70s funk and British post-punk—was complex yet rhythmically tight, and his soloing, although influenced by his classic-rock heroes, veered far from the blues scale and often incorporated unusual note choices and dissonance.

The Minutemen toured hard and their profitable low-budget road trips are legendary. They were also prodigious in the studio and left behind a large catalog of albums, EPs, videos, and live footage. They were just beginning to get noticed, too—their final tour was opening for R.E.M.—when Boon was killed in an auto accident in late 1985. He was only 27. It was a tragic and untimely end to a story that was just getting started. His bandmates almost called it quits, but eventually regrouped and went on to much greater acceptance, and even a major label deal, as Firehose, among many other projects and collaborations.

But Boon had made his mark. His playing, energy, outlook, and idealism have inspired a generation of musicians. Other guitarists often cite him as a primary influence. He was an outlier, an individual, and not interested in becoming a rock star. He became one anyway, albeit posthumously, although like everything associated with the Minutemen, it’s probably more accurate to call him something else—and to acknowledge that he did it, as the band would say, “econo.”

Boon’s story has been told many times and in many forums, but, surprisingly, very little has been written about his playing, tone, gear, and experiences in the studio. We reached out to Boon’s former bandmates, Watt and Hurley, as well as Spot (Glen Lockett), who was the house engineer and producer at SST Records and the engineer on many Minutemen sessions, in addition to his contemporaries Nels Cline (Wilco) and J Mascis (Dinosaur Jr.), to compile a musical snapshot of an idealistic, influential, and sorely missed talent.

Corn Dogs from Pedro

D. Boon was born on April 1, 1958, and raised in San Pedro, California, a neighborhood about 20 miles south of Hollywood. Blue collar and middle class, San Pedro was the opposite of its northern neighbor. Mike Watt was Boon’s childhood friend and the pair became musicians at the insistence of Boon’s mother. She thought it was a way to keep them out of trouble. “Our first guitars were pawnshop,” Watt says. “I think D. Boon had a Melody Plus. His cost $15 and mine was $13. Mine was a Teisco.” Boon played guitar and Watt played bass, not that they knew what that meant. “I only had four strings on my guitar because that’s what I thought a bass was,” Watt says. “I took the B and the E string off and now it was a bass. I didn’t know it was tuned lower. I had no idea.”

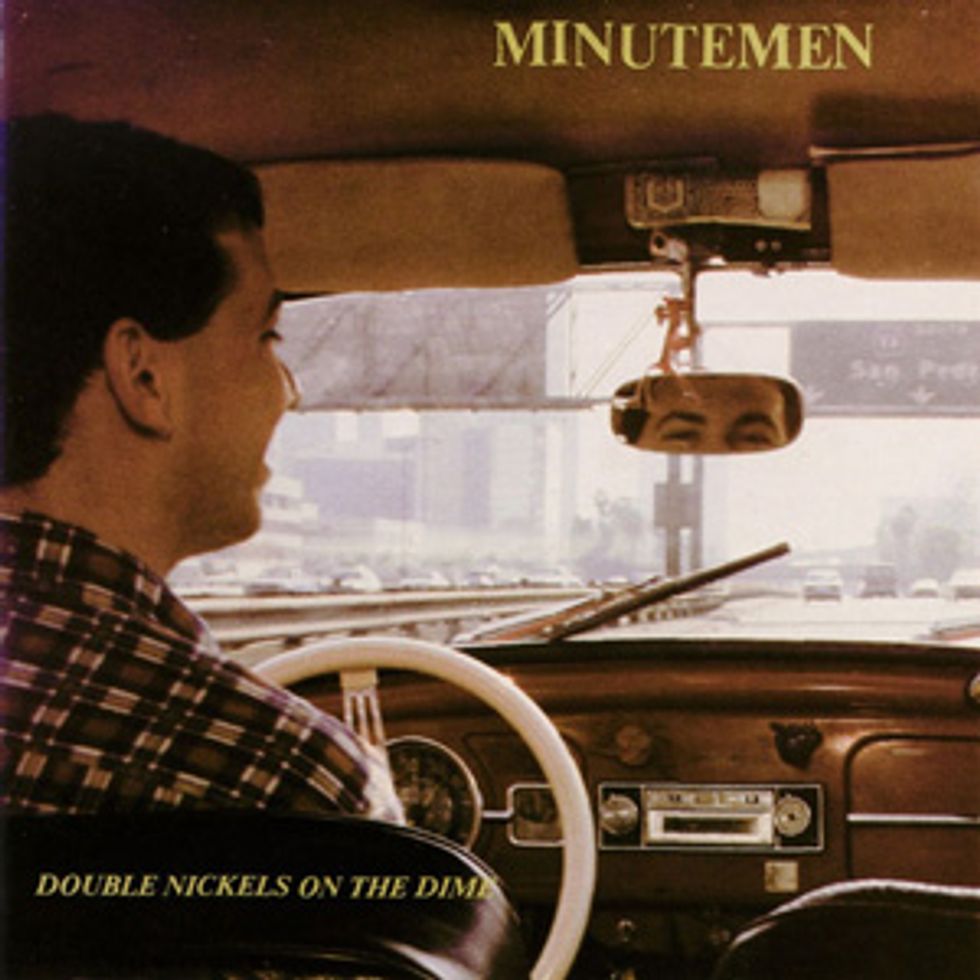

With 33 songs, the band’s two-LP classic Double Nickels on the Dime strove to recreate the variety of songs and rapid-fire urgency typical of the Minutemen’s concerts.

Boon grew up listening to the music his father listened to: country star Buck Owens and Creedence Clearwater Revival. “When I first met him, the only rock band he knew was Creedence,” Watt says. “John Fogerty was a huge influence on him.” Watt turned Boon on to Blue Öyster Cult and their guitarist, Buck Dharma, as well as the Who. “He was a strange mix of John Fogerty and Buck Dharma. And then I turned him on to the Who and he got into Pete Townshend.”

Boon and Watt spent time together after school, learning songs off records—a tedious process in the days of low-budget turntables and 8-track tapes—and rehearsing the songs they knew. Sometimes it was with Boon’s brother Joe on drums, but more often playing along to the record. It was painstaking and slow, but Boon built up impressive chops, which made him stand out in the early days of punk.

“I remember the first song was ‘Suzie Q,’ and him running that down after school every day,” Watt says. “D. Boon never used record covers and so his records would be on the deck and covered in grape juice, and you’d have to put six quarters on the stylus to keep it from skipping. It was terrible.”

Boon also took a handful of lessons on nylon-string acoustic from Roy Mendez Lopez, a colorful local character who made a big impression him. “He would teach him songs off records,” Watt says. “But then he would sneak in other stuff—some Vivaldi, some Bach, and he showed D. Boon some flamenco.” You can hear the Spanish influence in Boon’s later playing—particularly in his use of fingerpicked arpeggios and on his solo feature, “Cohesion,” off the 1984 release Double Nickels on the Dime. But perhaps Lopez’s biggest influence was on Boon’s work ethic. “He did impress upon us one thing: practice, practice, practice,” Watt says. “And that was one thing about me and D. Boon … and still today, with my bands, I practice every day.”

Boon and Watt started to play in bands together. They played covers—mainly rock staples by the Stones, Alice Cooper, Black Sabbath, and others. They finished high school, started college, and that probably would’ve been the end of their music careers. Writing songs and making records was not something they thought people like them did.

But then they discovered punk.

For Southern California punk bands, a ritual of acceptance was performing on the L.A.-based New Wave Theatre TV show with host Peter Ivers, from 1981 to 1983. When the Minutemen appeared, Boon played the parts S-style guitar that he

used to record the 1980 Paranoid Time EP. Photo by Spot

The ethos of punk—playing in small clubs, writing songs, and doing it yourself, the scene’s emphasis on community and its acceptance of misfits and outsiders, and even its left-leaning politics—spoke to them. It validated their ambitions. It gave them permission to break rules. It taught them that art was within their grasp. It also exposed them to people who were very different from those in San Pedro. They didn’t immediately become punks, but they soon formed their first band, the Reactionaries (with Hurley on drums), which after a few fits and starts morphed into the Minutemen.

Their big break came when they met Black Flag in a parking lot outside a Clash show. “We opened for Black Flag in February of 1978,” Watt says. “I think it was their second or third gig. It was our first gig.” Some members of Black Flag were handing out fliers for an upcoming show in San Pedro. “We couldn’t believe they were trying to play a gig in Pedro,” he continues. “We said, ‘We’re from Pedro and we’re the only punk rockers in that town.’ They said, ‘There are punk rockers in Pedro? Do you want to open?’ It was fucking like that; we didn’t even know them and they asked us to open.”

In 1980, Greg Ginn, the guitarist in Black Flag and the head of then-nascent SST Records, invited the Minutemen to record their first EP. “I met them at a show,” Spot says. “At that time, D. Boon had a mohawk and was wearing coveralls. They were playing these super-short songs and I thought, ‘Whoa, this is geeky.’ But then I thought, ‘This is really good geeky.’ They didn’t have anything recorded as far as I knew; maybe some practice tapes or something, but that wasn’t even an issue then. It was just, ‘Let’s get these guys in the studio and do something because it will definitely be good.’”

Those first sessions, which resulted in the EP Paranoid Time, featured a band with a large repertoire, a distinctive sound, and low-budget gear. They upgraded their instruments as the years went on, but simple, utilitarian gear was an ideal Boon stayed true to.

“D. Boon had a guitar that by any standards people would consider a piece of junk,” Spot says. “It was a Frankenstein Strat. It had a typical ’70s neck—probably a 3-bolt heel—with maple fretboard, big headstock, and bullet truss rod. The bridge pickup was a normal-looking single-coil. The body may or may not have been Fender. That was the era of third-party DiMarzio, Mighty Mite, Schecter—or whatever was cheapest—stuff. It was a guitar he put together that had been just parts. It had paint splattered over it. It was not a prime-looking instrument any way you looked at it, but it was his instrument and he knew how to make it sound.”

Watt adds, “He also had a single-cutaway Melody Maker and put a Strat pickup in that. He got that from Dezo—Dez Cadena—of Black Flag. He had a buddy make him a pickguard out of sheet aluminum so it wouldn’t break. It just had a volume knob and that one Stratocaster bridge pickup. He played that for a few years until I got him his first Telecaster, because he always wanted a Telecaster.”

Low-Budget Gearhead

Boon’s cheapo guitars were similar to what many other punks were using. High-end gear, as you’d expect, was expensive and beyond the means of most early punk rockers. But they were making an aesthetic statement as well. “Late ’70s and early ’80s punk/trash/noise bands were notorious for gutted pickup wiring, intentional or not,” Spot says. “There was a pride in making the most basic, cheapest system work. By the mid-’80s, attitudes got a bit more urbane or ‘professional.’”

D. Boon’s penchant for low-cost, ad-hoc gear applied to his amps as well. “He had an old blackface Fender Bandmaster head,” Spot says. “At that time, it was considered the low version of a Fender piggyback.” He also had a 2x12 cabinet with mismatched speakers, which were wired out of phase. “I recorded it in stereo. I had each speaker miked separately. When I was mixing the stuff down, I tried to see how everything sounded in mono and the guitar disappeared. That’s when I learned, ‘Whoops, this ain’t going to work.’”

Regardless of the gear he used, Boon always sounded like Boon. His tone was unique—even unusual—and not something most guitarists aspire to. “D. Boon would play all treble,” Watt says. “He would turn down all the tone knobs except for the treble, which would go all the way to the top. It was a total cheese-slicer sound.”

“Thank God I was behind that amp,” drummer Hurley recalls. “He used a Fender Twin Reverb with the treble turned mercilessly high. I remember seeing a few unsuspecting people jump up and run.”

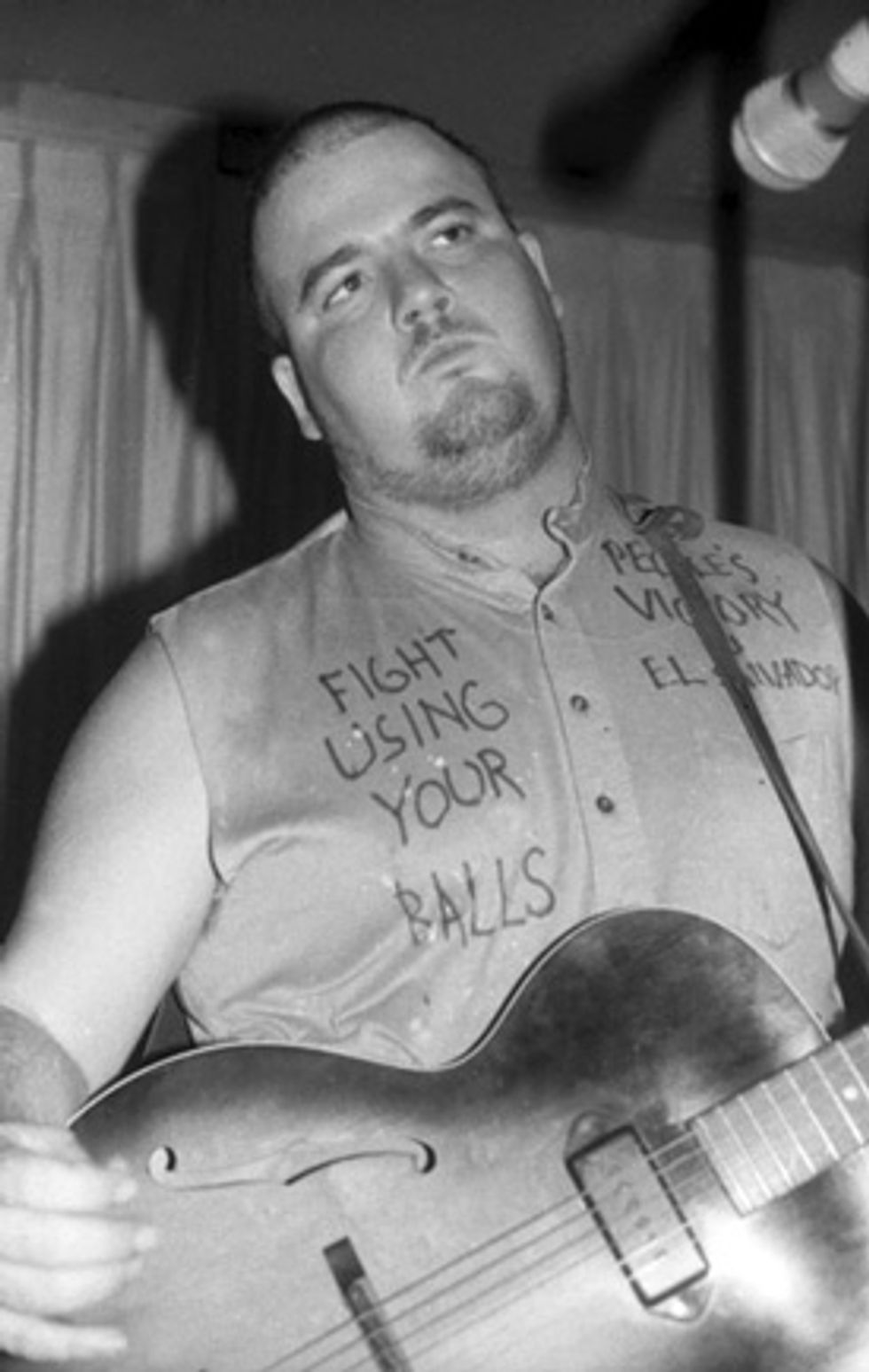

Usually Boon wore his punk ethos on his sleeve, but this time it’s a bit higher. The guitar he’s wearing is the ES-125 he used for overdubs on the band’s magnum opus, Double Nickels on the Dime.

Photo by Bev Davies/Courtesy of Mike Watt

J Mascis, no wallflower when it comes to volume, adds, “It was definitely the most ear-damaging show I ever went to. I stood in front. He had the treble all the way up with bass rolled all the way down. It shredded my ears more than any other gig I ever went to.”

But Boon’s tone, as distinctive as it was, wasn’t just a preference. It was in sync with the band’s political outlook as well. “Watt and D. had very deliberately created sovereign states,” Nels Cline says. “One state was identified as ‘treble’ and the other as ‘bass.’ They stayed out of the way of each other’s frequencies in a way that was ‘political,’ which means—I think—that they had cooperation and respect for each other’s ‘territory.’”

“The political part of the Minutemen wasn’t the words,” Watt says. “D. Boon called those, ‘thinking out loud.’ The political part for D. Boon was how the band was structured. Obviously, we were just a power trio, but he wanted to make room for the drums and the bass. He liked the way the R&B guys restrained themselves—this idea of restraining yourself so you made room for the other guys in the band, instead of this hierarchy.”

Punk promoted independence and rule breaking, and paid lip service to anarchy. But like most movements, it became established and rigid. Hardcore, in particular, had set rules, and bands were expected to sound a certain way.

But that didn’t apply to the Minutemen.

In addition to their classic-rock roots, they borrowed from British post-punk and learned from bands like the Pop Group and Wire. “The Pop Group were basically putting Captain Beefheart together with Parliament-Funkadelic,” Watt says. “We liked that idea, too—the idea that you can do whatever you want. We never saw the movement as a style of music. It was more like permission to try anything. Put Funkadelic with Beefheart? Do it. We thought that was really interesting.”

That same spirit inspired another Minutemen trademark: short songs. Most of their songs were less than two minutes—many were less than one—but their songs weren’t supposed to be stand-alone. They were mini-movements and part of a greater symphony. “A Minutemen gig was to try and make one song out of 30 or 40 parts,” Watt says. “We got the idea from Wire, but we also thought it would purge some of that rock ’n’ roll we learned off the records.”

Purging those influences explains their cavalier attitude toward establishing a musical style as well. “We didn’t think motifs or style,” Watt says. “Those were all devices to help us spell the word ‘Minutemen.’ We didn’t want to be a ska band or a reggae band. We could play anything—that was the idea—and still you could tell it was the Minutemen. During the gigs, there would be three or four times during the set when we’d play free jams for a minute or two. We did a lot of that. But the songwriting—we wanted it short and the songs were concise.”

The story of the Minutemen is also the tale of the lifelong friendship of D. Boon and bassist Mike Watt, at right. According to Nels Cline, the two pals had their own “sovereign states. One was identified as ‘treble’ and the other as ‘bass.’”

Photo courtesy of Mike Watt

“I Felt Like a Gringo,” off their album Buzz or Howl Under the Influence of Heat, is quintessential Minutemen. It also encapsulates many of the qualities in Boon’s playing. The song’s primary theme is a unison odd-metered line, with hyper-fast funk comping under the vocals, and a guitar solo that starts with an extended quote from the Champs’ 1958 hit, “Tequila.” It eschews the standard verse/chorus formula and clocks in at under two minutes.

That minimalist approach applied to the studio, too. Their first full-length album, 1981’s The Punch Line, was recorded at Media Art Studio in Hermosa Beach, California. “We had an old Tangent 3216 console, which, frankly, I thought was a great-sounding board,” Spot says. “It wasn’t considered the most state-of-the-art board, but for what I call ‘gut-bucket music,’ you could really get a good sound going to tape.” The recording was quick, as was the mixing, and it required very little EQ. “At one point I realized, ‘Wait a minute, these tracks don’t need any EQ on them.’ The rough mixes of the basic tracks on a cassette sounded incredibly good, and they were coming off the machine straight—no EQ, no nothing. I think there were one or two tracks that I needed to put a little compression on, and maybe something through an outboard EQ, but other than that, everything else was just a raw signal with no reverb or any kind of effects on it.”

“The first records were kind of like gigs,” Watt adds. “We even played them in order so we didn’t have to spend money on sequencing.”

But as simple as their approach was, they refined that even more. “Paranoid Time and The Punch Line were done on a 16-track machine,” Spot says. “What Makes a Man Start Fires? was 24-track. But somewhere in that whole thing, Mike was grousing about the multitrack stuff. He was a guy who, kind of like me, was very much influenced by the jazz approach, where you go into the studio, do it live, and don’t worry about any of that other stuff. I found a studio up in Hollywood. It was an 8-track studio, and the guy who owned the place said, ‘If you really want to go for what you’re describing, why don’t you just do it live to 2-track?’ And that was one of the best things I ever heard.”

Playing for Change

Spot recorded the tracks for Buzz or Howl Under the Influence of Heat live to 2-track. They didn’t use that approach for their next album, their magnum opus, Double Nickels on the Dime, but it was definitely done “econo”—a term the band coined and lived by.

“That record cost $1,100,” Watt says. “Almost all that stuff is one take. D. Boon went back though and overdubbed some lead guitar. And it’s 8-track. It’s kick, snare, toms in stereo, bass, guitar, vocal, and then maybe guitar overdub. That’s all the tracks.”

he was proud of it.” —George Hurley

The overdubbed solos on Double Nickels, as well as on subsequent sessions, were done at the behest of Ethan James, the engineer and owner of Radio Tokyo, where the album was recorded. (James was also the keyboardist in a late-’60s incarnation of Blue Cheer.) Boon used a Gibson ES-125 for those overdubs. The guitar had a soap bar pickup in the neck position and he ran it through an Ibanez Tube Screamer. But other than on those overdubs, he almost never used distortion or effects.

By that point, Boon was using much better gear. “He had a Super Twin,” Mascis says about Boon’s amp. “It was a 180-watt Twin with six tubes, from the late ’70s or early ’80s.”

“After his Bandmaster amp, D. Boon pretty much fell in love with Twin Reverbs,” Spot says. “The Twin Reverb was what they would call a ‘proper amp.’ It was a silverface. It had a master volume control on it. His was a good one.”

Boon’s guitar of choice at that time was a Telecaster. He had at least three. “You can see him playing the first one when you open up Double Nickels on the Dime,” Watt says. “It’s black with a white pickguard. Then on that tour, ‘Campaign Trail ’84,’ we played Canton, Ohio, and he got his rosewood Telecaster. After that we found his purple one. The purple one is the one he really liked.”

“D. experimented with a few different guitars,” Hurley says. “His Fenders were his favorite. If his sound was rude with plenty of attack, he was proud of it.”

“D. Boon favored Telecasters, he used a lot of treble, and he sweated like crazy,” Cline recalls. And that sweating caused electrical problems with Boon’s guitars.

“We had a problem with sweating at gigs,” Watt agrees. “It would soak the pickups and shut out all the high end, which, for D. Boon, was like, ‘What? No high end?!’” The solution, eventually, was to use EMG pickups, which were sealed in epoxy. We took out the pickup—for a little while there was a Seymour Duncan blade pickup in there—and put in the EMG, so we wouldn’t have to deal with the sweat. That fat one—the humbucker in the neck position—he hardly used that. He used that sometimes for sustaining when he wanted to play like Curt Kirkwood from the Meat Puppets, but he always used the bridge pickup.”

Boon was playing his Gibson Melody Maker during this 1983 gig. Note the sole, single-coil pickup in the bridge position and the aluminum pickguard, as well as the “customized” output jack. Photo courtesy of Mike Watt

Boon favored heavy gauge strings—usually D’Addario .012’s—and gray .88 mm Dunlop picks. “He liked heavier strings,” Watt says. “They stayed in tune better. More tone, more piercing. He got that from Randy Bachman.”

Double Nickels showcases the full range of Boon’s style. His hyper-fast, funk-style comping is in full force on songs like “West Germany” and “The Roar of the Masses Could Be Farts,” and is often juxtaposed with drastically different sounds, like mellow jazzy chords, twangy solos, or unusual riffs.

“I think he was drawn to certain sounds and notes he thought were interesting or even jazzy,” Cline says. “Hence his playing was rarely just pentatonic. He started on classical or Spanish guitar and as such, early on, he may have learned something about scales without actually knowing theory. He was hearing more than just a so-called ‘blues scale.’”

The album also includes songs like “Corona,” which plays off a Latin-influenced chord progression; “Jesus and Tequila,” which is a great example of Boon’s oddball phrasing; and a few covers including “Dr. Wu” (Steely Dan) and CCR’s “Don’t Look Now.” The album’s hit—if you could call it that—was “This Ain’t No Picnic,” which is one of the few Minutemen songs to use a standard verse/chorus formula.

The band continued to tour and returned to the studio twice more to record the EP Project: Mersh and the album 3-Way Tie (For Last). They had a successful run supporting R.E.M., performing their last concert of the tour in Charlotte, North Carolina, on December 13, 1985. But then, on December 22, 1985, Boon was thrown from the back of a van after the driver dozed off and lost control. He broke his neck on impact and died instantly.

And with that, the Minutemen called it quits. There was only one D. Boon. “That’s a band that could only have been those three people,” Spot says. “How each of those guys played and when they played had everything to do with how great they were.”

“At heart they were punks,” Cline adds. “Including, discarding, and challenging the notions of music-making, and expressing themselves as self-determined artists—not emulating the rock establishment and pining for general acceptance. They were mavericks and visionaries: passion and no pretension.”

“People ask me, ‘What kind of bass player are you?’” Watt says. “I say, ‘I am D. Boon’s bass player.’ Almost everything I do comes from playing with that guy. D. Boon had a sincerity in the way he sang, the way he played, and the way he presented himself at a gig that really blew people away. I thought that was such a human quality—a fabric to bring us together without somebody having to have his boot on your throat. I was glad to be part of the human team with D. Boon.”

Punk Tone’s Mr. Clean

The toll D. Boon’s sweat took on his instruments makes this Telecaster look like a battle-scarred warhorse. Note the sealed EMG pickup in the bridge position.

Photo courtesy of Mike Watt

D. Boon liked his tone one way: clean and bright as a freshly shampooed polar bear in a blizzard. His ingredients were essentially Fender or Fender-inspired, starting with a Melody Plus electric solidbody guitar that was made in Japan and acquired for a mere $15. By the time the Minutemen recorded their debut EP, 1980’s Paranoid Time, he’d thrown together an S-style instrument from parts of now-forgotten origin. Than came the Telecasters—the model he played until his tragic death just four years later. He had at least three—each acquired as an improvement on the previous one, including the natural rosewood guitar he played on his final tour. The exception was a severely beaten single-pickup Gibson Melody Maker that he played in the band’s early years, which he nonetheless made sound like a Tele—thanks in no small part to sporting just one single-coil pickup, in the neck slot.

Boon used zero effects, other than his imagination, to conjure the jolting, prickly riffs that branded his individuality as a stylist. And his amps, once he had the spending money, were a succession of Fenders—a Bandmaster, perched atop a rough-hewn mutt of a cabinet with two mismatched speakers, followed by a Super Twin, and then Twin Reverbs, which he revered for their cleanliness and loudness. He turned the bass and mids off, and jammed the treble up to 10, often making his notes sharp as a pirate’s dirk.

His clean live tone marked him as different from most of the guitar players of the punk and post-punk years, and it was all the more astonishing for the precision of his lines—despite that fact that he almost constantly capered onstage while he riffed and soloed.

Éminence grise rock critic Robert Christgau summoned up the loss of this singular virtuoso in his review of the Minutemen’s final album, 3-Way Tie (For Last), which was released the month that Boon died: “I tried to cut myself a little critical distance in the wake of a rock death that for wasted potential has Lennon and Hendrix for company … After seven amazing years, he was just getting started. Shit, shit, shit.”

D. Boon Essential Listening

Want to draw a bead on D. Boon’s singular guitar style? Check out these videos:

“D. had a powerful rhythm guitar thrust, putting his whole body into it,” Nels Cline says. You can see that in action in this 1985 clip shot live at the Stone in San Francisco, as he wails on “I Felt Like a Gringo” from Buzz or Howl Under the Influence of Heat.

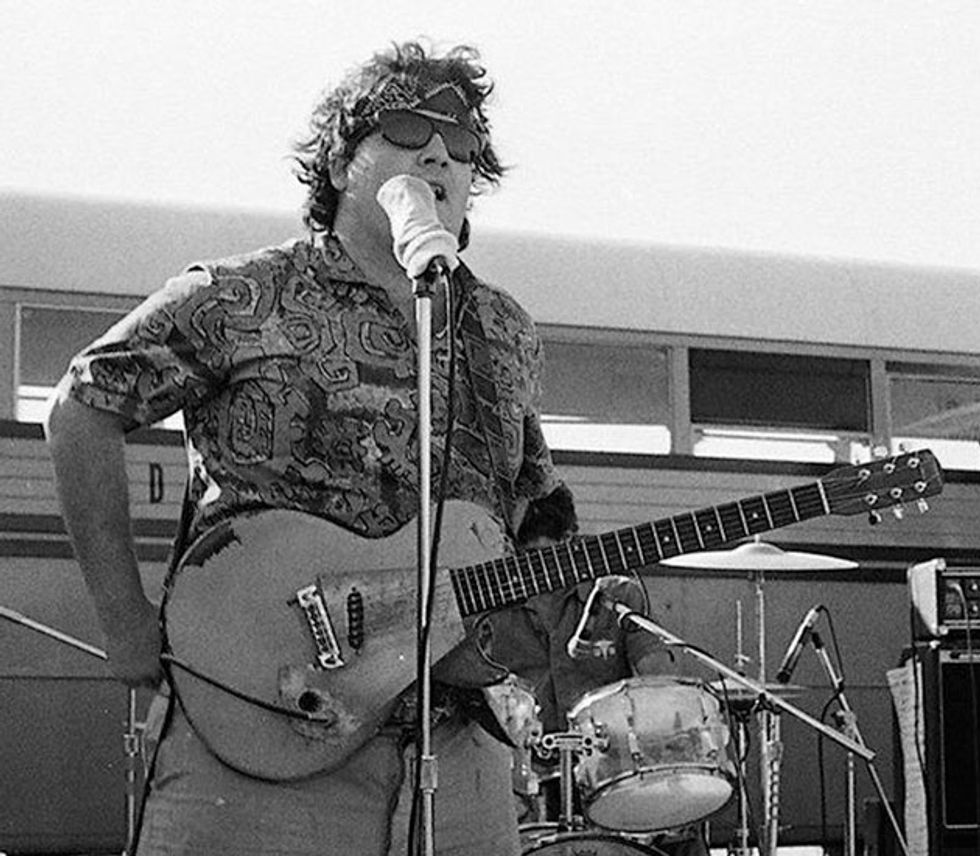

So clean it practically hurts, D. Boon’s tone is in full idiosyncratic bloom during this performance shot outdoors on the UCLA campus with Boon’s roommate, Richard Derrick, filling in on drums. “He really was into that chunky attack with a quick response,” regular Minuteman drummer George Hurley says. “When he would strum his guitar, his legs would catapult his torso into the air.”

The chugging, studio-recorded audio for this video for “Bob Dylan Wrote Propaganda Songs” is from 1983’s What Makes a Man Start Fires? According to Spot, reading from his log for the sessions, “On the guitar, I see an [Electro-Voice] RE20 and a [Beyer] M 500. There were two room mics: one was a Neumann U 87 omni and the other was an AKG C414 bi-directional.”

This performance is about as dirty as D. Boon got in the studio—with a slightly abrasive quack to his tone. “This Ain’t No Picnic” is from Double Nickels on the Dime. “At the time, we thought [having chops] was a taint,” Mike Watt says. “We were poisoned. We were soiled. We were not just brand-new playing. But we figured, you can’t change your past anyway, so fuck it.”

A highlight of the Minutemen’s live shows was the wild array of meat-and-potatoes rock covers they’d pull out. Here, they play Van Halen’s “ Ain’t Talkin’ ‘Bout Love” during the brief period when Boon used a Gibson Melody Maker with a single-coil pickup and an aluminum pickguard.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)