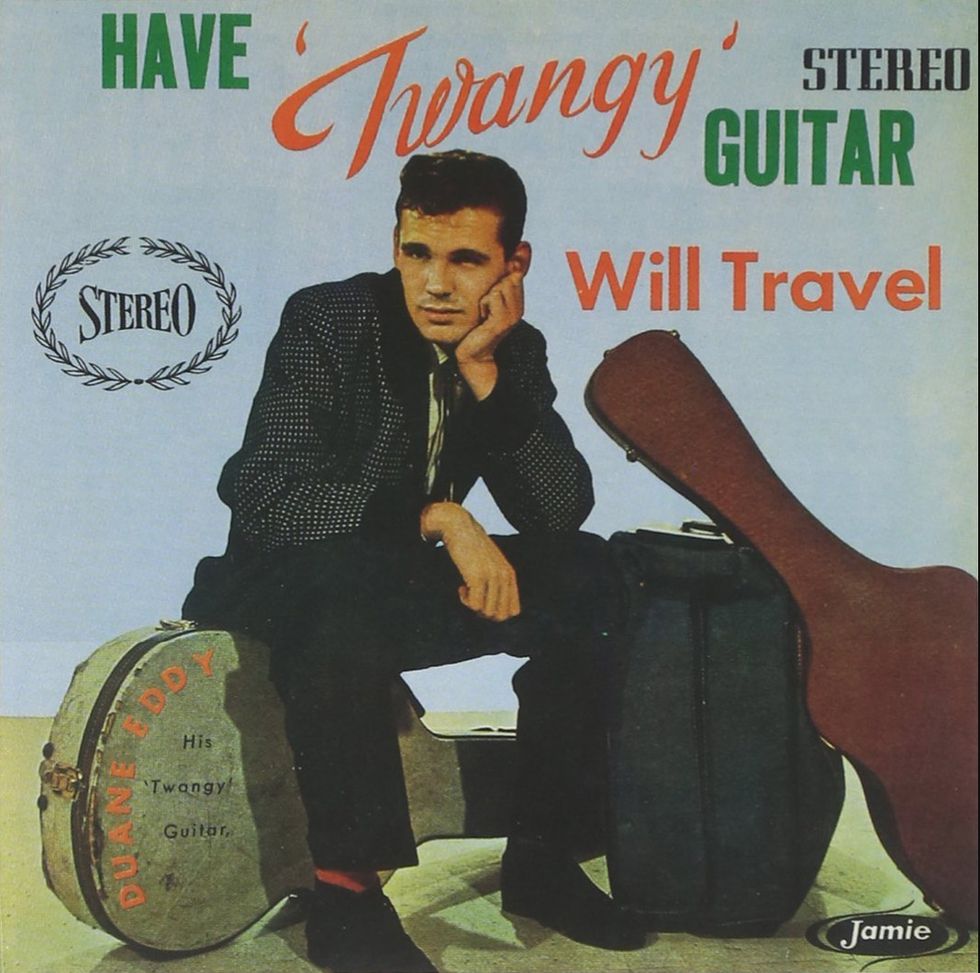

With the rise of the Americana genre, the term “twangy guitar” is often tossed around, but twang itself is far from new. It’s hard to think of anyone who represents this low, clean, reverberant, guitar tone more than Duane Eddy, whose 1958 debut album was called Have “Twangy” Guitar, Will Travel. (His third album was called The Twangs the Thang.)

But Eddy’s reach ranges further back and farther afield than his effect on the sound of Americana. Among those who acknowledge his influence are George Harrison, Dave Davies, Hank Marvin, the Ventures, John Entwistle, Bruce Springsteen, Adrian Belew, and Mark Knopfler. And acknowledged or not, it’s hard to imagine the American guitarist wasn’t an influence on the Western movie soundtracks of Italian composer Ennio Morricone.

If you’re still fuzzy on exactly what “twang” means, give a listen to Richard Bennett’s instrumental hook for Steve Earle’s “Guitar Town.” It’s unadulterated twang and straight from the Eddy playbook. Like Chuck Berry and Albert King, if Duane Eddy had a dollar for every guitarist that’s appropriated his sound, he could buy a small (or maybe not so small) island.

Born April 26, 1938 in Corning, New York, Eddy was playing guitar by the age of 5. In 1951, his family moved to Coolidge, Arizona, where, at 16, he formed the duo Jimmy and Duane with school friend Jimmy Delbridge. During a performance at a local radio station, they met disc jockey Lee Hazlewood, who produced a single for them in 1955.

After the duo split, Eddy and Hazlewood had a string of 1950s instrumental hits including “Rebel Rouser,” “Cannonball,” Ramrod,” “Peter Gunn,” and “Because They’re Young,” and by 1963, the 25-year-old guitarist had sold 12 million records. The majority featured his trademark technique of picking out melodies on the low strings of a reverb-drenched Gretsch (reverb courtesy of a buried water tank at Phoenix’s Audio Recorders studio). Added to this formula were background vocals (wordless or otherwise), a sax solo, and occasionally some shouting for added excitement, before restating the melody. Though known primarily for his bottom-heavy twang, delving deeper into his output reveals Eddy is an adept picker in the Chet Atkins style and a soulful blues player as well.

Eddy’s records often reflected the music of the times. They might contain covers of the pop hits and dance crazes of the day, or exclusively tunes by and associated with Bob Dylan. There are also delightful divergences, like an album featuring only acoustic guitar and banjo, 1960’s Songs of Our Heritage, recorded to capitalize on the Folk Revival of the early ’60s, and The Roaring Twangies, a collection of big-band backed twang.

Eddy’s post-’60s solo output has been sparse but choice. In 1986, the guitarist collaborated with the British avant-garde, synth-pop group Art of Noise to again record the Henry Mancini-composed television theme “Peter Gunn.” When the single became a hit in England, he cut additional tracks with Paul McCartney, Jeff Lynne, George Harrison, Ry Cooder, James Burton, and Steve Cropper for what would become the 1987 Duane Eddy album. Another 24 years passed until Road Trip, the best instrumental Americana record you have likely never heard. Produced by former Pulp member and Lee Hazlewood fan Richard Hawley, it manages to respect Eddy’s art without being self-consciously reverent.

But the father of twang was not sitting around idle between solo outings. Often, artists wanting the Duane Eddy touch would be canny enough to call the man himself. Eddy appeared on albums by Nancy Sinatra, Emmylou Harris, Kenny Rogers, Doc Watson, the Pretenders, and even Foreigner. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994.

Though part of American musical history, Eddy is a long way from being a candidate for the “oldies” home. Listen to the track “Livin’ In Sin” by Dan Auerbach and you’ll hear an explosive, twangy, Eddy guitar solo. About to turn 80 in 2018, Eddy is all over the Black Keys guitarist’s 2017 solo record, Waiting on a Song, with many more tracks residing in Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound Studio just waiting on the next atmosphere-drenched album by the often imitated, never duplicated Titan of Twang.

TIDBIT: Eddy’s 1958 debut album included a slew of his early classics: “Rebel Rouser,” “Cannonball,” “Ramrod,” “Detour,” and “Three-30-Blues” among them.

When did you start playing guitar?

When I was a little over 5 years old, I was down in the cellar with my dad and saw this thing against the wall. He showed me a few chords. It hurt like heck at first, but I gradually got used to pressing down hard enough to make it work. I didn’t know you could play up the neck for another three or four years, until I saw somebody do it. My dad bought me a Kay about three years later.

What was your first electric guitar?

My aunt bought me an Electromuse lap steel and the little amp that went with it when I was 9. It came to a fiery end. I took it in for some repairs and the damn store burned down.

When did you switch over to a regular electric guitar?

After we moved to Arizona, I bought a goldtop Les Paul for $75 in a hardware store in a little town south of Phoenix in about 1954. A guy in town made these orange-crate amps with a 12" speaker and chicken wire in the front. I used that for the first couple of years. Then, around 1957, I was at Ziggie’s Music in Phoenix looking at guitars. I looked at a White Falcon, but it was too expensive and didn’t play that great. They brought out an orange 6120 and handed it to me. It sat in there just so beautifully and the neck was a dream. I thought I would come back with my father to co-sign for me. I picked up my Gibson and started out. Ziggie said, “Where you going?” I replied, “I’ve got to get some dinner and go to work.” “Don’t you want to take this with ya?” he said. I said, “We haven’t signed anything.” He told me, “It’s your guitar, take it. When your dad gets back, have him come by and sign the paperwork.” I left there a happy camper. My dad didn’t get there for about three months. [Laughs.]

What kind of music were you playing when you first started?

I played country music. I grew up on Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, Red Foley, and Elton Britt. The first job I had with a country band paid $15 on a Saturday night at the VFW.

At New Orleans’ Ponderosa Stomp in 2010, Duane Eddy picks out one of his trademark melodies on his favorite signature guitar: a Gretsch 6120 with a Desert Sunrise—aka orange—finish. Eddy acquired his first 6120 in 1957 at Ziggie’s Music in Phoenix, Arizona. Photo by Joseph A. Rosen

How did you learn to play country?

I taught myself by playing along with the radio. I had to be able to tune like a wiz, because not everything was in 440. The songs would be just under or over and I had to tune up real quick. The next tune might be off the other way. We couldn’t afford to buy records.

When did you pick up the Chet Atkins style?

I was about 16, living in Coolidge, Arizona. My dad managed a Safeway store. The local DJ came in and dad said, “My son plays guitar.” The DJ said, “Bring him out to the station and we will record something.” I recorded some Chet Atkins songs and he played it the next morning on his show. All the kids getting ready for school were listening to the station. One, named Jimmy Belridge, came running up to me at school and said, “You want to come to my house and play music?” Jimmy played piano and I played guitar. That fell apart when he got saved and couldn’t sing pop music anymore.

When did you meet Lee Hazlewood?

I met him in Coolidge in early ’54.

What prompted the first Duane Eddy record?

In 1957, Bill Justis and Ernie Freeman were both in the top 10 the same week with an instrumental called “Raunchy.” Lee Hazlewood said, “Why don’t you write an instrumental?” So, I wrote “Movin’ and Groovin’.” We released it on a little Philadelphia label, Jamie Records. It was about No. 70 on the charts for three weeks.

How did you develop the concept that became your signature of playing melodies on the low strings of the guitar?

I had done sessions as a sideman in Phoenix, where I played on the high strings. One day I played something on the low strings and noticed it was lot more powerful. I went to the studio one morning with this idea for a melody, which was “Rebel Rouser.” I played the melody and told Lee we could have a sax answer that. He took it to L.A. and had Gilbert Bernal overdub sax. Bernal was an old jazz honker that worked with Louie Prima and Spike Jones. He could do this real raunchy thing.

Do you tune the whole guitar down to get that big sound?

Sometimes I tune the E string down to a D. I had to tune the low E down to D for “The Ballad of Palladin” from the TV Show Have Gun–Will Travel.

Are some of the songs played on a baritone or 6-string bass?

They were. In ’59, I discovered a Danelectro 6-string bass, which is an octave lower than a regular guitar. I thought, “This was made for me.” I used it on one of my bigger hits called “Because They’re Young.” On my third album, I used 6-string bass on all the songs except two.

What amp were you playing through onstage?

We all had these Magnatones with two 12" Jensens. They were about the best on the market at the time, unless you went for a really expensive amp, like the Standels that Chet used.

Did you ever use a Fender amp?

The Magnatone was bigger—65 watts or something. These two local guys would boost it up over 100 watts through a single JBL 15" speaker and a tweeter. They would cover the amp with Naugahyde and a white grille cloth and charge us $100. That’s where my sound came from. It wouldn’t break up no matter how hard you hit it. I compared it to a Standel at Manny’s Music in New York one time. I would hit the Standel real hard with a note, or turn it up beyond a certain point, and it would break up. I plugged back into mine and turned it up even louder and it would not break up. I realized I had the best amp in the world.

What gauge strings were you using at that time?

Medium gauge.

Were they flatwound or roundwound?

Roundwound.

Guitars

Gretsch 6120 Duane Eddy Signature models in Desert Sunrise, White Pearl, and Black lacquer finishes, all with Bigsbys with the “Duane Eddy” handle and Tru-Arc bridgesGretsch Duane Eddy

Signature 6-string bass guitar (to be released in 2018)

Amps

Fender Super-Sonic Twin

Effects

MXR tremolo (No longer in production)

Atomic Brain preamp by the Nocturne Brain (modeled after the ’70s preamp from the Roland RE-301 Space Echo)

Strings and Picks

Custom GHS Boomers (.0095, .011, wound .020, .034, .044, .054)

Did you move your pick closer to the bridge when you wanted a brighter sound?

Yeah, I picked about three or four inches off the bridge. It gave me a sharper bite when using a straight pick. A lot of people thought I was right on the bridge, but I just hit it hard—that’s part of my touch.

“Movin’ and Groovin’” opens with a Chuck Berry type of lick at the beginning.

I found that out later. I heard a guitar player in Phoenix playing that lick one day.

You had never heard Chuck Berry do it?

No, I hadn’t. It was kind of a country thing. That’s probably where Chuck got it, too. It’s a little different than mine, but it’s similar. When I met him, I said, “Who do you listen to, Chuck?” He said, “Kitty Wells and the Everly Brothers.” I said, “Kitty Wells? That’s country.” He said, “Well, I’m a country boy, I grew up listening to country music.” So, I figured he probably heard something off a country record.

“Ramrod” has a different sound than other tracks of that time.

That’s because Lee sped up the tape. We cut it in A and he sped it up to B, which gave it a real sparkle. He ran out of money and couldn’t do a B side, so he put it out on Ford Records with Al Casey doing “Caravan” as the B side, on which I only played rhythm. I told him not to, but they put my name on both sides. I was worried radio would start playing “Caravan” instead, and I can’t even play the damn thing. Al just cracked his knuckles and said, “That’ll never happen.” They put it out and it did absolutely zippo, nothing.

After I had a hit with “Rebel Rouser” on Jamie records, I went on Dick Clark’s show. When we finished “Rebel Rouser,” Dick said, “We would like you to do something to open the show. How about ‘Movin’ and Groovin’?” Then he asked what I had for a closer. I didn’t have many things recorded, except “Ramrod.” We did it and I didn’t think anything more about it. Monday morning, the record company called in a panic and said, “Where’s this record, ‘Ramrod?’ We’ve got 150,000 orders on our desk.” I called Lee and he added Plas Johnson on sax and the Sharps on background vocals on Tuesday, mastered it Tuesday night, sent it over to the pressing plant where they pressed it, and shipped it Thursday. By Friday, it was starting to show up in stores—less than a week after I played it live. That was my third chart record and second Top 40.

Over the decades, Eddy has collaborated with such A-list musicians as George Harrison, Emmylou Harris, Steve Cropper, Ry Cooder, Paul McCartney, and, most recently, Chrissie Hynde and Dan Auerbach. Auerbach and Eddy have cut tracks for Eddy’s 2018 album, and are shown here working with John Prine at Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound Studio in Nashville.

Photo by Alysse Gafkjen

I’m curious about a track like “Three-30-Blues.” Who were your blues influences?

I hadn’t heard blues that much. The Sharps sent me down to a club in the Watts section of Los Angeles. There was a ’40s-style big band playing blues. It seemed like the same chords as country but more minor notes. They wanted me to play “Movin’ and Groovin’.” I listened to what the other guys were doing and finally the bandleader points to me and says, “Go!” I shook my head. He pointed again and says, “Play.” So, I just did what I could feel. We got to the end of the verse and the bandleader made a circular motion like, “Go around again.” I really let it go, and that night I learned to play the blues.

You did some experimental stuff on your records, like “The Scrape,” where you play the melody by scraping the strings.

That was with a straight pick and I just scraped each note on the string. You’re the first person to ever mention that tune.

In addition to your own records, you’ve worked with a surprising variety of artists, like Nancy Sinatra.

I did that with Jimmy Bowen. He was teaching me about producing. He said, “You can pick some songs for me, I hate doing that.” When he did Nancy, I picked a lot of the songs for her. I also produced the last album that Lee Hazlewood ever made. He had produced me and then I produced him.

Didn’t you play on an Emmylou Harris record?

It was the first thing I did when I came to Nashville. I played on “I Had My Heart Set on You” on her album Thirteen.

What was it like working with the British electronic band, the Art of Noise?

They had a track already cut. I flew over and took the green Gretsch Country Club. I didn’t want to risk losing my orange 6120. In the ’80s they were calling Heathrow Airport “Thief-row,” because so many guys were losing guitars. I overdubbed the guitar part on the Art of Noise track. I changed the outro so I had a little more to play than just the riff.

That ended up on the 1987 Duane Eddy record, but you worked with Paul McCartney, Ry Cooder, and Jeff Lynne on the other tracks.

When the single with the Art of Noise became a hit, Jeff Lynne said, “I know you’re going to have a hit album. Call me and I will produce, write, play, or whatever you want me to do.” So, when I got the album deal with Capitol, I called Jeff. He said he couldn’t do it because he was working with George Harrison. I told him I understood. The phone rang 20 minutes later and it’s Jeff saying, “George asked me who called and I told him. He wants to put his album on hold and do yours.” I went over and we did three tracks with Jeff—two that George played on.

Did you do the McCartney track while you were there?

Yeah, I went down to his studio and did “Rockestra Theme” there.

put out next year.”

When did you do the tracks with Ry Cooder?

We came back to California and did that at Capitol. Then we went out to the valley to do “Kickin’ Asphalt” and “Last Look Back” with my old guys, Jim Horn (arranging and playing horns) and Larry Knechtel (keyboards). James Burton and Steve Cropper were on those.

What amps were you using after the Magnatones?

A guy named Tom McCormick in Phoenix talked to the two guys who did the Magnatone modifications to get their design, and built his own amps. His name was actually Tom Howard McCormick and they called the amp a Howard.

Are you still using those Howard amps?

I would, but now Tom is dead, and I took the last one I had to a guy who said it was wired all wrong and then screwed it up.

What are you using these days?

I’m using Fender now. They gave me two 65-watt amps at first, and I used them both. That worked okay because I could hear myself when I walked around the stage, but they’re miking the amps these days so they come through the monitors anyway. I wanted a more powerful one, so they gave me one that’s over 100 watts. They don’t make the 15" JBL D130 anymore, so they put in an Eminence that’s supposed to replace that D130. It doesn’t have the midrange, but it has more highs.

What was it like working on 2011’s Road Trip with Richard Hawley?

He was a great guy to work with: very kind, encouraging, and funny. He and Jarvis Cocker from Pulp are both big fans of Lee Hazlewood. I had walking pneumonia when we cut that album, and was about to pass out between takes.

You wouldn’t know to listen to it. How did you hook up with Dan Auerbach?

Dave Ferguson, who owns the Butcher Shoppe Recording Studio in Nashville, asked if we could all have lunch. I figured a buffalo burger would be safe. Later on, Dan said, “I hate buffalo burgers.” [Laughs.] I didn’t see him for several months after that, until I went down to the Station Inn one night where I saw him singing high harmony with Del McCoury. Besides being a Black Key, Dan is a bluegrasser. He can sing tenor to a dog whistle. His uncles all played bluegrass and he grew up with that.

Did he call you for the Chrissie Hynde record he was producing?

Even before Chrissie’s record, he called one morning about 9:30 and said, “Can you be at the studio by 1 o’clock?” So, I went down and he had me play. I had my tic-tac bass guitar, not the Dano. Gretsch made me a 6-string bass that I’m going to put out next year. We used that sometimes for a 6-string bass solo, or I played my regular guitar for the solos.

Which record was this for?

They’d written a song called “Gospel Twang” and wanted me to play that and another one I can’t remember now. I’m all over his new album, but at the time I was just playing on tracks. I didn’t know if they were for Dan’s record or Chrissie’s. We did a couple of instrumentals, too, with just him playing drums and me playing guitar. We’re going to go back in and do three or four more with a whole band. We did one song where I’m playing guitar and he’s playing a little rhythm on his gut-string and singing that just breaks my heart.

When is the next Duane Eddy record?

This year is my 60th anniversary [of the release of “Rebel Rouser”], so I’m going to have a new record and an autobiography.

Duane Eddy gets back to his roots with the Americana Music Association Honors & Awards house band at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium in 2013, picking out “Rebel Rouser” on one of his signature Gretsch 6120s.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)