Tom Morello’s approach is raw, direct, and purposeful. Early in his career, after years spent developing formidable skills that include blazing shred chops and mad melodic invention, he switched gears and decided to amplify the idiosyncrasies and “mistakes” in his playing. That led to his unique tonal footprint, which is immediately recognizable since many of his heaviest riffs are played on a single-coil pickup and he employs a bevy of extended techniques that include simulated record scratching, a kill switch effect, Public Enemy/Bomb Squad-style faux samples, and soloing on a live unplugged quarter-inch jack. And he does all that with a basic, no frills, unchanging rig.

Morello’s gear choices are conservative. That’s his word, which he uses without irony. He employs the same Marshall head he’s used since Rage Against the Machine’s early days, his pedalboard is limited and fairly conventional, and his guitars are inexpensive workhorses. But despite his—can we say it?—boring setup, Morello’s guitar playing is a sonic wonderland. The myriad oddball bleeps and grunts he wrangles from his staid signal chain are non-guitar-like and seemingly never-ending. Examples are rife throughout his extensive discography with Rage Against the Machine, Audioslave, and Prophets of Rage, plus solo releases, and it’s an approach he continues with his latest recording, The Atlas Underground.

The Atlas Underground was a work-in-progress for several years. Every track is a collaboration. It includes live jams that were dissected and reconfigured in post-production, curated emails chock-full of riffs, and a Cubist approach to reimagining guitar sounds—and was recorded at multiple studios around the country.

In our conversation, Morello, forever on a mission, advocated on behalf of The Atlas Underground. He also spoke about finding his voice as an artist, his unusual approach to heavy riffs, his advice for beginning guitarists, and his experiences playing with the E Street Band. Morello also happens to be on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nominating committee, so in addition to everything else, we didn’t waste the opportunity and lobbied for deserving artists (like Iron Maiden, obviously).

You’ve mentioned that The Atlas Underground is like a Hendrix album.

Sure. I’m not so much approaching it like a Hendrix album, but approaching it with the goal of being the Hendrix of now. There are three parts to that. But first of all—not to misrepresent to any of your readers—that does not mean a psychedelic blues-rock guitarsploitation record. That’s been done before, and perhaps too many times. What I mean by the “Hendrix of now” is: 1) It’s a record that has to have otherworldly, extraordinary guitar playing. 2) It’s a record that serves as a Trojan Horse in a way that Hendrix records did, where it put crazy guitar playing on the radio. He forced a generation to deal with the fact that the electric guitar was a formidable and far-reaching divining rod of truth and fury. And the third element is the genre. At the time in which Hendrix played, the principle genre was blues-rock. Well, the principle genre of now has electronic components to it. My idea was to forge a new genre that takes elements of aggressive EDM music, but replaces the synthesizers with my electric guitar to create a bold new alloy of something that’s unapologetically rock ’n’ roll, but futuristic at the same time.

You’re like a stealth warrior, sneaking the guitar back on radio.

Exactly. One thing that really pisses me off is that a lot of young people are now just reaching for their laptops and getting Ableton, which is fine, nothing wrong with that. But the commitment to practicing eight hours a day in a room to really hone your craft and your musicianship, to be able to express yourself through the incredible instrument of the guitar—that’s not an ambition for a lot of young people anymore. I want to change that.

How did you put this album together?

Different songs were written in different ways. For example, the tune that I did with Gary Clark Jr., “Where It’s At Ain’t What It Is,” came from a three-hour jam that he and I had at my studio. We recorded the whole thing and then I went through it to find the choicest riffs and the best turns of phrase. I made a three-and-a-half-minute song out of that three-hour jam, with a turbo charged beat to it, in a way that recontextualizes his and my playing. For “Battle Sirens,” which is one of the heavier songs, which starts the record, with [Australian electronic-music duo] Knife Party, I would send them a riff tape: “Here’s 10, maybe seven, big riffs. Here’s five crazy guitar noises. Here’s a bunch of shreddy bits.” With the idea being that if my guitar playing is like the black-and-white photograph, then what I want to hear is the smashed-up Picasso version of that, where it’s recognizable as me, but it’s heard in an entirely different way.

TIDBIT: For “Where It’s At Ain’t What It Is,” his collaboration with Gary Clark Jr., Morello boiled a three-hour jam down to a three-and-a-half-minute song.

Are the actual guitar recordings that you sent heard on the final song?

Absolutely. Sometimes when they sent the song back to me, I played on top of it. We went back and forth that way. A lot of my guitar playing in the past has been influenced by not just heavy rock ’n’ roll, but by hip-hop and by some electronic music—by playing in an analog way the textures and sounds of different genres of music, to bring it back through the Marshall amp. With this, it was creating these crazy Frankenstein monsters, where you don’t know where the guitar begins, where the guitar ends, and where the electronic components begin. A lot of the stuff on this record that you might think is electronic button pushing is actually me playing the guitar. Because that’s how I sound—like R2D2.

Did you plug direct into your computer or was it still an amp miked up in the studio?

It’s always an amp miked up in the studio. Always. I’ve been using the same Marshall JCM800 50-watt, channel-switching 2205 head, and that’s really what I trust and gives me the signature tone that I feel most at home with. It’s really the same limited number of effects pedals: Cry Baby Wah, original DigiTech Whammy pedal, little digital delay pedal, and an EQ pedal that I use exclusively for boost.

And that’s your rig. Do you always approach the studio the same way? You wheel in your amp, plug it in, mike it up, and that’s your sound.

That’s right. I’m very conservative when it comes to the gear part of it. But I try to let go of the reins when it comes to the creativity and the imagination side. So, with a limited amount of gear, I’m aiming for far-reaching sonics.

Did you program the beats or was that your collaborators?

I didn’t do any programming—there are some live drums as well—and while I oversaw the production of each of the songs, that’s not my forte. I also wanted to get out of my safety zone. This is the 17th studio album that I’ve made and the other 16 have been made in a more traditional way. I wanted to push myself as a guitarist and as an artist to do something that was exciting and challenging.

On some songs, like “Rabbit’s Revenge,” where there are “looped” guitar parts, are your parts actually looped or did you play that part throughout the entire song?

That’s me playing through the entire song. That one came about with Bassnectar. His name is Lorin [Ashton]. He and I were in my studio and we were having trouble finding the right riff to really do what we needed it to do. I was warming up, playing the figure, and he said, “What’s that?” I said, “Just warming up.” He said, “Did we record it?” I said, “Yeah, I think we did.” He said, “That’s the jam.” And I was like, “That’s the jam?” He had an idea for the groove and when I played that riff over that groove I was like, “Holy shit, that’s the jam.”

Although Morello keeps a fresh musical mindset, he’s also got a vocabulary of hard-honed technique and old-school stage moves that provides a foundation for his quest to be “the new Hendrix.” Photo by Annie Atlasman

You mentioned that you jammed with Gary Clark Jr. Is jamming something you like to do? I ask, because it sounds like your approach, in general, is more compositional.

Recently, I’ve gotten back to playing a lot of exploratory guitar shredding. I just played a couple of shows in Brazil where 70 percent of the shows were instrumental music. That’s the thing: Back when I was practicing eight hours a day, I was doing two or three hours every day of just pure improvisation. In my shows that I’ve been doing for The Atlas Underground, I’ve returned to that a lot. Sitting around at home, I really like to focus my creativity on songwriting, riff writing, and trying to translate big ideas through the amplifier, but lately I’ve really been enjoying getting back to improvisational shredding my ass off. Like, I’ll put up a seven-minute backing track of the solo section from “Mr. Crowley” and just jam over that. It’s just so much fun. [Laughs.]

Talk about finding your voice, developing unorthodox techniques, and advice to new players.

I didn’t start playing guitar until I was 17. The only other guitar player that I ever heard of that I liked, who started that late, was Robert Johnson, and he had to make a deal with the devil to get that—and I wasn’t going to do that. I had to knuckle down and practice. When I was 17, I started practicing an hour a day every day. Then it went to two hours, then four, then eventually eight hours a day without fail—partly because I have obsessive-compulsive disorder and partly because it was my way of catching up.

But even through all that, for years, I was amassing technique and becoming a very competent musician, but I really wasn’t an artist. It really wasn’t until the beginning of Rage Against the Machine, where I self-identified as the DJ in the band, that I started looking at the guitar in a very different way. I was no longer practicing Phrygian scales. I was practicing the eccentricities in my playing, the mistakes in my playing. Recognizing that the electric guitar is a relatively new instrument on the planet—it’s just a piece of wood with six wires and some electronics. You can manipulate it in a lot of different ways. Once I had that revelation, I was off to the races. I was unconstrained by the conventions of whether it’s Chuck Berry playing or Eddie Van Halen playing or whatever, and started making up my own vocabulary of sounds to build songs around.

How did you practice that?

Some of it was looking at the instrument with very innocent eyes and going, “What if somebody just handed you this thing without saying you have to put your finger on this fret?” I’d go, “Okay, along with this guitar came an Allen wrench. I know that you’re supposed to use it to unlock these things so you can tune the strings, but what if I rub on the strings or whack it against the strings while I’ve got a wah-wah pedal on?” That’s how [Rage Against the Machine’s] “People of the Sun” was written, and it was written in about two-and-a-half minutes. I would use the toggle switch as a way of fretting notes, and that just made the guitar sound like a crazy keyboard. Then I added the DigiTech Whammy pedal, and all of a sudden you could sound like a Deep Purple distorted organ or like the production on a Dr. Dre record. I just kept going. I would listen to whatever sounds were around me and try to play them. If it was a lawn mower outside or a helicopter overhead or a trip to the zoo, I would try to practice that stuff. Even if I couldn’t make it sound like a lion or a paper shredder, if you’re practicing lions and paper shredding rather than blues scales, you’re going to be thinking about music in an entirely different way.

Did you also try to find a different voice in effects?

No. Not usually. I have imposed these conservative parameters on my gear. On the one hand, I’m not very technically savvy. I’m not scrolling through apps in order to find things. I continue to find a huge sonic diversity in a very limited number of pedals.

Every once in a while, I’ll throw … like on the last Prophets of Rage record I played a thing called a [Way Huge] Swollen Pickle, which I liked, so I got into that for a couple of songs. There’s also an old DigiTech Space Station. In the mid ’90s, DigiTech basically tried to steal all of my sounds and put them in a pedal and called it the Space Station [laughs]. I got one of those and I started stealing some of their sounds back.

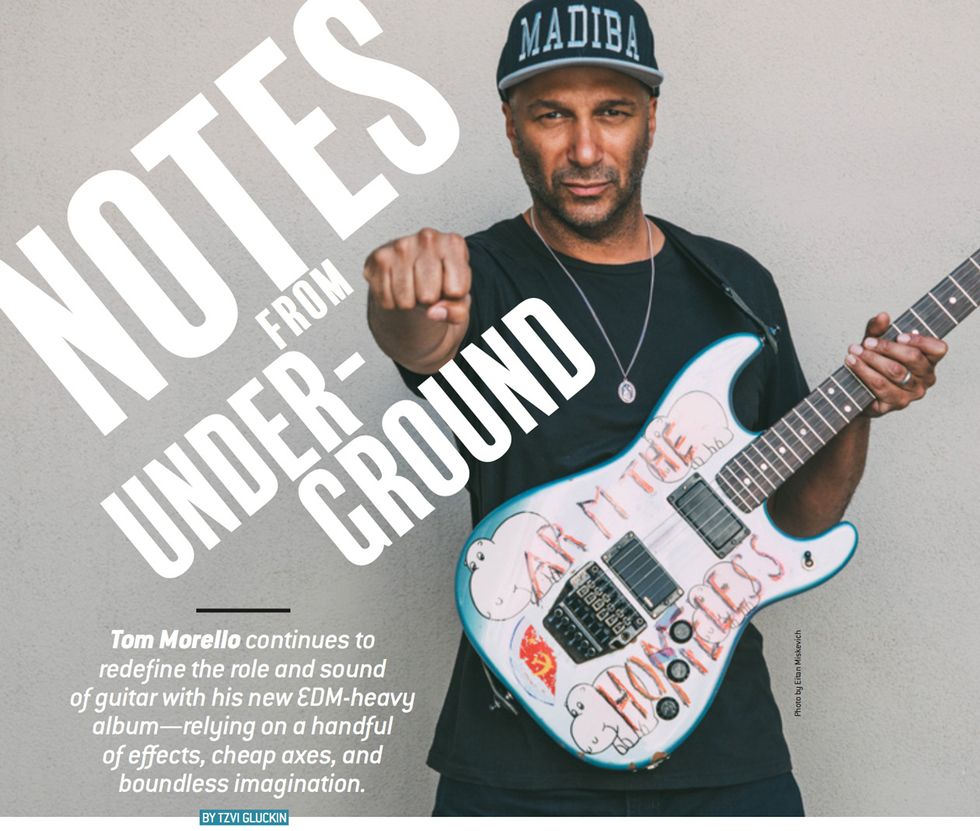

Guitars

“Arm the Homeless” parts guitar with an Ibanez Edge vibrato, EMG pickups

Mid-’80s Fender Telecaster in drop D

Early ’70s Kay double-cutaway

Gibson Les Paul with Budweiser finish

’90s Gibson EDS-1275

Amps

Marshall JCM800 2205 50-watt head

1987 Peavey 412 cabinet with Celestion G12K-85 speakers

Marshall 1960B 4x12

Effects

Boss TU-3

Dunlop GCB95 Cry Baby Wah

DigiTech WH-1 Whammy

Two Boss DD-3 Digital Delays

DOD FX40B Equalizer

MXR Phase 90

DigiTech Space Station

MXR Talk Box

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Hybrid Slinky (.009–.046, for vibrato-equipped guitars)

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046)

Modified Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.056 on low string dropped to B)

Dunlop Tortex Jazz III

Watching you play, especially with Rage Against the Machine, it looks like you let the other members of the band do the heavy lifting in terms of making it heavy. Do you find that the less you play, the heavier it is?

One of the things that I find, that’s attributed to the “heaviness” of my riffs, is a lot of them are played on a single-coil pickup. That is counterintuitive to a lot of guitar players who think it’s got to be the gnarliest tone ever. You listen to some of the Zeppelin records where Jimmy Page is playing that on a Telecaster. Or he’s playing it on the rhythm pickup through a small amp on the Les Paul. A lot of it has to do with the player’s right hand and the rhythm section. And, fortunately, I’ve been playing with Timmy [Commerford] and Brad [Wilk], who are one of the heaviest rhythm sections of all time. Tim’s bass tone would often sound like two basses and four guitars playing all at once. I’d have my guitar playing, like, “Killing in the Name”—that’s played on a Telecaster. “Freedom”—that’s played on a Telecaster. The riff from, “Cochise,” from the Audioslave catalog, that’s played on a single-coil pickup. And those are pretty heavy-ass riffs, but it’s looking at the guitar in a different way.

How did you get your rhythm chops together?

Metronome is very important to getting your time together—though how I learned rhythm chops, when I was doing my eight hours a day, two of those hours every day was just playing along with the radio. I would randomly switch stations and whatever station I landed on, I would try to be in the band. If it was a classical station, then I was forced to try and play along with Bach or Mozart, and if it was a New Age station, I’d have to play along to whatever major 7th jazzy chords were going along, or if it was a metal station I’d have to fit in with Sepultura. To me, that was a great learning tool—trying to fit into a lot of different environments—and that helped my rhythm playing a lot.

Do you recommend people do that as well?

I think it’s a tremendous education, and you don’t need any preparation. Whatever level you’re at, you just put on—today people may rely more on streaming services or whatever—but to challenge yourself by going outside of your comfort zone. If your comfort zone is metal, then spend three days just playing along with bebop music. If your specialty is blues, spend three days playing along with EDM or classical music, and try to figure it out. Pretend that you were parachuted into that set and what are you going to do? For me, it really helped a lot and it challenged me. Another great learning tool, especially for beginning players, is write your own songs. When I taught guitar and when I had people come for their first guitar lesson—who had never played a chord before—I would teach them two chords and the first thing I’d have them do is write a song. It’s no longer, “Oh my gosh, I have to work hard for three years before I can be in a band.” No, you don’t. You can write a song today. You learn a G chord and a D chord and now you and Bob Dylan have songs that are similar [laughs].

Do you use non-standard tunings?

Drop D is a big part of my repertoire and a big part of my riffing heaviness. I’ve fooled around occasionally with drop-B tuning, if you want to go even lower and heavier.

What do you enjoy about working with other guitar players?

A lot of times, I’ve been very selfish in the bands that I’ve been in, where I like to take up all of that midrange myself. But I had a great experience playing on and off for six years with the E Street Band. They have a number of guitar players and it was really great to, first of all, learn from them. Nils Lofgren is really wonderful—to watch the way he plays. To trade solos with Bruce Springsteen, who’s a very accomplished lead guitar player—emotional lead guitar player—and then Steve Van Zandt as well, who has his own unique style and has played some all-time classic-solos on those Springsteen records. That was really great, to fit in with those guys.

Talk about Springsteen’s guitar playing.

He’s a really good guitar player. I mean, of course, we all know he’s a great songwriter, but as a beginning point, if you want to check out Bruce Springsteen’s guitar playing, the entire Darkness on the Edge of Town record is a guitar tour de force, and his solos, those Telecaster piercing emotional solos on that, are timeless. That’s all him.

You’re on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nominating committee. When is Iron Maiden getting in?

Well, they should’ve been in a long time ago, as should Judas Priest and Motörhead and Thin Lizzy—the list goes on. I will say this, since the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has let me in—I complained about it so much they finally let me in the room—we’ve seen Rush, Kiss, and Stevie Ray Vaughan in the Hall, so I’m doing the best I can.

Which era of Maiden do you prefer, Paul Di’Anno or Bruce Dickinson?I love them both. I’ll say this: My favorite Maiden record is Piece of Mind, but my favorite Maiden song is “Wrathchild.” I got one foot in each camp.

Live from the Teragram Ballroom, Audioslave rages against Donald Trump. Tom Morello’s solo at the 2:52 mark displays his ability to build a melody out of rhythm playing with his DigiTech Whammy pedal—a technique that won him attention with Rage Against the Machine’s first single, “Killing in the Name,” in 1992.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)