Photo by Erich Francois

“When I hear other bass players playing like me,” says Larry Graham—the funk god who invented and popularized the electric-bass slapping-and-popping technique with Sly and the Family Stone in the late 1960s—“I just think, ‘There’s another one of my children!’”

That’s a lot of kids. The technique— heard in megahits such as “I Want to Take You Higher” and “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)”—won Graham a page in music history and went on to become a cornerstone technique for players from Stanley Clarke to Bootsy Collins, Marcus Miller, Les Claypool, Flea, Doug Wimbish, and Victor Wooten, each of whom has spawned his own fanatical following, thus exponentially increasing Graham’s influence. Indeed, although Graham prefers to call the technique “thumpin’ and pluckin’,” it’s no overstatement to say that his playing has impacted the world of electric bass with the same force and universality that Jimi Hendrix’s did for the electric guitar.

Graham has been leading his own Graham Central Station band for nearly four decades now, and his first album in more than a decade, Raise Up, proves the legend hasn’t slowed down a bit. With newly recorded versions of GCS classics like “It’s Alright” and “Now Do U Wanta Dance,” as well as fresh new tracks like “Throw-N-Down the Funk,” Raise Up both frames the breadth of Graham’s legacy and demonstrates his band’s potent live sound. In addition, the album features cool cameos by players such as Raphael Saadiq and Prince—who plays drums, keyboards and backing vocals on the title track, and lays down liquid lead-guitar tracks on “Shoulda Coulda Woulda.” Throughout, GCS churns out funk fire and finesse, with Graham dialing up fuzzy, phased tones in spots, and longtime guitarist William Rabb and blazing new drummer Brian Braziel turning in dazzling performances on a furiously funky cover of the Stevie Wonder classic “Higher Ground.”

“I’m very fortunate,” says Graham. “All of our players were raised on my music, and at the same time they’re very open to progression. So they can play the old stuff as close to the originals as possible, but when it’s time for where we’re going next, they’re all right there.”

We recently spoke to Graham, 66, about his pioneering playing and the influence he’s had on the world of bass guitar. Like many veterans who’ve been at it their whole lives, he’s at the point where gear and tone settings are secondary or even tertiary to feel and vibe. He prefers to let his recent music speak for itself, but he was more than happy to talk about the cataclysmic funk that one inspired player with fantastically attuned hands and ears can deliver.

You get a really full-throated

tone on the new album. How

do you capture your sound in

the studio?

I close-mic the amps in the

studio—because I want that

amp sound—but I still record

direct, as well, because I want

the cleanness and the power

and the punch from the direct

sound. Once I record them, I

blend the two by ear to make

it sound the way I want it. It’s

different, live: I don’t mic the

amps onstage, although I do

send a direct signal out of the

back of two of the amps to the

mixing board.

What were you trying to

accomplish with Raise Up?

I intended it to be a complete

piece, like a book, with a great

beginning, a body of content in

the middle, and a great conclusion.

The idea was to create a

complete journey. That’s why

I wanted to include some of

the early GCS stuff, as well as

the current stuff. It’s also why

I wanted to include Prince—because of this close connection

between him and me—and also

Raphael Saadiq, being out of

Oakland, and Stevie Wonder,

being such a close friend and

having done so many things

together. I think it really says

what I’m all about. If you were

to pick up a book and read

about me, that’s what it would

sound like!

Can you tell us a bit about

your songwriting process?

A lot of it’s just singing the

parts into a tape recorder before

I even get a chance to sit down

with the instrument. Sure, if

I’m at an instrument—say, a

guitar—I’ll play the chords,

like I did when I wrote “Ole

Smokey,” which is a guitar-type

tune. Songs like “Today” or

“Just Be My Lady” or “Hold

You Close” are things I wrote

on the piano. A song like

“Hair” is obviously built around

the bass, so it was written on

the bass. “Got to Go Through

It to Get to It” is built around

a pretty intricate drum beat,

so in that case the beat came

first. I’ve been blessed to have

learned quite a few instruments,

and though I’m not a master

of those instruments—no

one’s going to ask me to be the

drummer in their band—I can

lay down the parts I hear in my

head, and many times I’ll even

keep those parts in the final

recordings. If I record something

at home that works great

and I can’t seem to duplicate it,

I’ll keep that, too. I played guitar

before the bass, and I played

the drums before that—so, I’m

not locked into any one method

of songwriting. However [the

song] comes, I’m going to move

forward from that.

Over all these years, you’ve

steadfastly stuck to calling

your revolutionary technique

“thumpin’ and pluckin’.” Let’s

talk about why you like to

make that distinction.

Well, it really is thumpin’ and

pluckin’! You can give it another

name, but it’s still thumpin’

and pluckin.’ When you hit

the string with the side of

your thumb, you’re thumpin’

it more than slapping it, and

when you’re poppin’ that G

string, like I do on “Thank You

(Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin),”

you’re really pluckin’ it. Y’know,

for people who aren’t musicians,

I can understand why they don’t

understand that—and they can

call it anything they want, as

long as they’re referring to the

same technique. I’m sure that

in the future, some new names

will get added—I’ve heard

“pop bass,” and “chopper bass,”

which is what some people call

it in Japan. There’s a whole list

of names, depending on where

you live, but when you see and

hear it, it’s all the same thing.

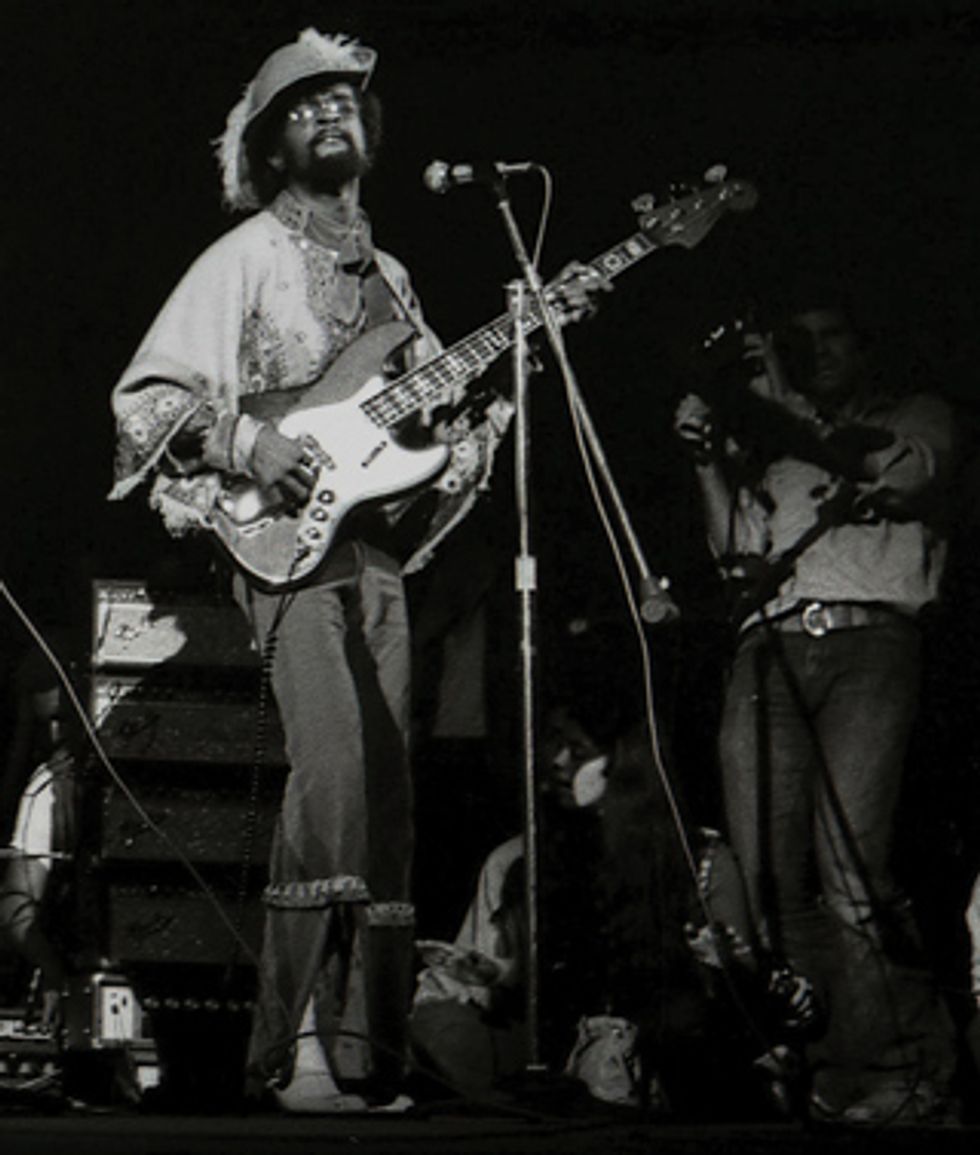

Larry Graham lays down the funk with Sly and the Family Stone at the Woodstock Festival in 1969. Photo by Jason Laure (Frank White Photo Agency)

Has the style you developed

way back in the ’60s changed

much over the years?

My technique is fundamentally

the same as it was back in the

late ’60s, because my heart

hasn’t changed—and when I

play, I play from the heart. Of

course, you grow in your understanding

of harmony, your

grasp of different feels, and you

benefit from exposure to other

people’s music. I mean, since I

came up with this style, we’ve

all lived through so many different

genres and styles, and the

way that I play the bass has now

spread throughout all genres of

music. So, my style is basically

the same, but everything I’ve

experienced as a person, as a listener,

and as a player all comes

out in my playing now.

Do you remember the first time

you thumped and plucked?

Y’know, the first time I played

bass I didn’t immediately start

thumpin’ and pluckin.’ Before

then, in my mother’s group

[the Dell Graham Trio, which

Graham joined at age 15], I was

on guitar and my mother was

on piano and we had a drummer.

So when I would take a

solo, she would be playing the

bass lines with her left hand on

the piano, and when she would

solo, then I would play bass

lines on the guitar. So the biggest

influence for me, in terms

of bass patterns, at that time,

would be her left hand. Later,

when my mother decided to no

longer use drums—and I still

don’t know if that was mostly

for economic reasons—that’s

when I started to thump the

strings to get that groove going.

But the way I started playing bass in the first place was that I had been playing the bass pedals of an organ with my feet at the same time as I was playing the guitar. We were getting used to having that extra bottom there, but at some point the organ broke down, so we missed the bottom. That’s why I went out and rented this St. George electric bass, and I rented it because I was going to take it back as soon as the organ was repaired! My first love was still the guitar! But it turned out that the organ couldn’t be repaired, and that’s how I got stuck on the bass. When my mom decided she was no longer going to have a drummer, that’s when I started thumping the strings—to make up for not having that bass drum—and plucking the strings to make up for not having the backbeat on the snare drum. I was basically trying to play drums on the bass to compensate for not having a drummer.

Larry Graham plays his signature Moon J-style bass with Graham Central Station at the B.B. King Blues Club & Grill in New York City on June 16, 2010. Photo by Adam Sands (Frank White Photo Agency)

Do you recall getting a strong

reaction from people when

you started playing that way?

I don’t remember any strong

reaction to it at the time,

though I remembering thinking

that if any professional

musicians heard me, they’d

think, “What is he doing? He’s

not playing the correct way.”

Meaning, y’know, the correct

overhand style of bass playing.

But the people at the club were

just enjoying what they were

hearing. When I look back, I

wonder if my style would have

ever meant anything to anybody

if Sly [Stone] hadn’t come down

and heard me at the club, loved

what he heard, and asked me to

join this new band that didn’t

even have a name yet.

But because of all those hit records we had, and because of other bass players seeing me on TV and wondering, “What is that guy doing?” it really caught on. Even in the ’70s, if you were in a cover band playing those Sly songs, you really had to play them the way I was playing them. So as a result of our success, other original bands started writing stuff that required their bass players to start thumpin’ and pluckin’ on their original songs. Of course, from there it spread even further. But until it became something famous, I really didn’t see anybody trippin’ on it. I never got that sort of “Wow, look what he’s doing!” People just seemed to enjoy my mother and I as a duo, with both of us singing and playing.

So where exactly does your right

hand thumb contact the string?

Most of the time, it hits the

string just ahead of the back

[J-style] pickup—between the

two pickups, but much closer

to the bridge pickup. You get

a slightly different tone back

there than you do if you thump

the string closer to the edge

of the fretboard—which I also

do, depending on the sound

I’m after. If you’re hitting it

closer to the pickup, it’s like

the difference between singing

up right on the microphone

or standing back a little bit.

Now, I do play overhand style

as well, but most of the songs

I’ve created incorporate the

thumpin,’ so that’s how I tend

to play. And this might sound

funny, but most of the songs

that other people have written

with me in mind also incorporate

that style, so it becomes

even harder to do things overhand-

style—other people have

sort of helped me to lock into

what I do even more.

And the popping or plucking

is always your index finger?

Yeah, it’s mostly the index

finger for popping—it’s the

strongest finger, and the one

naturally closest to the string.

So where do the ghost

notes come from—the percussive

stuff that’s often

non-harmonic?

A lot of that actually comes

from the left hand. You can hit

a ghost note with your left hand

that you can actually attack with

your right hand. And you can

accent notes just by how hard

you press down with your left

hand, even if you’re just playing

one note. Take, for example, on

“Everyday People”: That’s just

one note, but that rhythm—

that BIM-dup, BIM-dup, BIMdup—

comes about by how hard

you hit the string with your

right [plucking] hand. Harder

and softer, harder and softer.

But it also comes from how

hard you press down on the

notes with your left [fretting]

hand. That’s how you create

that sort of galloping rhythm

thing, even on just one note. So

both right and left hands have a

part to play in that.

The one change in your playing

over the years seems to

be that you’ve added more

melodic information, such as

in bass lines like “It Ain’t No

Fun to Me.”

Well, again, that comes from

growth within yourself. You

can know how to do something

pretty well, but as time goes on

you keep doing it over and over,

and that fundamental technique

just gets better and better. I

have to say that, these days, I

don’t think about playing that

much—I think a lot more

about the overall performance,

and that includes singing and

dancing, and communicating

with the audience. Of course, in

the studio, working on a record,

that’s a time to focus in 100

percent on your playing and

your parts and your technique.

It’s easier to focus in when

you’re concentrating on one

thing, and there’s no audience,

no distractions. In front of an

audience, though, I can’t just

stand there and play bass—well,

I could, but I’d get in trouble!

What are the biggest lessons

you’ve learned from being

both a legendary sideman and

a well-known bandleader?

All those years with Sly, and

with my mother before that, I

was quite comfortable following

the leader. I’ve always felt that,

though I’m in a contributing

role, I’m constantly learning.

With Prince, for example, very

often I’m in the background

role, just being the bass player.

Of course, with GCS, I’m out

front as the bandleader. So I’m

very comfortable and content

in either role. In other words,

I don’t have to be the leader. In

fact, I became a bandleader out

of necessity—I wasn’t seeking

the role! I was working with

Hot Chocolate as a producer,

and I was writing all the tunes

as well, so when I suddenly

found myself also in the band,

bandleader was the role I naturally

assumed.

Larry Graham’s Gear

Basses

Moon Larry Graham Snow White bass with Bartolini J

pickups and 27-volt Bartolini preamp

Amps

Warwick WA 600 class-A solid-state amps powering WCA

410 and WCA 115 cabinets

Effects

Ernie Ball volume pedal, Dunlop 105Q Cry Baby bass wah,

Danelectro fuzz, Roland Jet Phaser, Mu-Tron Octave Divider

Strings and Accessories

GHS Boomers (.035–.095), Ernie Ball straps

Obviously, I had great training and great role models, and I’ve seen a few bad examples— how not to treat band members. Sly was a great songwriter and producer, but one thing that was a part of Sly’s genius—and, I think, part of the band’s success—was that he allowed each person in the band to be themselves. He asked me to be in the band because of what he heard me do. So, if he’s going to write “Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” and he’s going to bring that to the table, why change up the way I play the bass? Just let me do my thumpin’ and pluckin’, like he heard in the beginning! Freddie Stone is a great guitar player— one of the greatest rhythm-pattern players—and though Sly is a guitar player, too, he wasn’t going to try to change up the way Freddie played. So I may play drums, but I’m not telling anyone they need to play it my way. Just bring the song to the people, and have them contribute what they do.

It’s the same thing with Prince: When we play together, I can be in the background playing bass on his stuff, or I can jump out front and be myself. He’s not trying to say, “Do it like this” or “Do it like that.” As a player and as a bandleader, that’s the way to enjoy what you’re doing.

YouTube It

Graham demonstrates his music-redefining

technique on GCS and Sly

classics. Note how the right hand

shifts position from the rear pickup

area to just beyond the fretboard.

GCS live at the Vienna Jazz

Festival, playing “Throw-N-Down

the Funk.” Dig Graham’s use of a

Roland Jet Phaser during the slap

breaks (e.g., at 2:10).

You won’t see much of Graham in

this live clip from Sly and the Family

Stone’s 1969 Woodstock performance,

but you’ll hear his rumbling

bass—including a throbbing solo at

3:10—powering one of the greatest,

sexiest grooves of all time. The influence

of this track on Miles Davis’

work of the era and into the ’70s is

unmistakable.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.