Jim Wysocki is a retired Mahwah, New Jersey, police officer and longtime friend of the late guitar legend, inventor, and musical innovator Les Paul. Their friendship began when Jim was just out of high school and grew into a relationship that lasted more than 29 years. Over the course of that friendship, Les presented Jim with a handful of vintage guitars, artifacts, and musical relics. Jim now displays many of these priceless mementos at a museum in Mahwah, and also shares his collection through the occasional Gibson bus tour—allowing anyone who is interested to touch, hold, and play Les’ gear.

Born Lester Polsfuss in 1915, Les Paul spent his life searching for the perfect sound, leading him to become one of the pioneers of the solidbody electric guitar and the multitrack tape recorder, as well as of rock ’n’ roll in general. A tinkerer and a firm believer in DIY, Les would make it if it wasn’t out there and he needed it—that’s just the kind of person he was. Les Paul died in 2009. He would have been 100 this year.

Jim was gracious enough to share with us some pictures of Les’ legendary gear, as well as some wonderful, heartwarming stories of their relationship. We hope you enjoy them as much as we did.

Rain, Snow, and a Danelectro

“Put it under your bed for a rainy day.” That’s what Les Paul told Jim when he gave him his first guitar in 1981, back when Jim was just a kid. He’d hear the phrase quite a few more times over the years, often accompanied by another guitar. Back then, Jim wasn’t “a music guy.” In fact, he hadn’t even heard of Les Paul prior to their first encounter.

“I was just out of high school, working a desk job at the police department,” Jim recalls. One winter night during a snowstorm, Jim got a call at the station. “The voice on the other end said, ‘Howdy, this is Les Paul’ … I didn’t know Les Paul from the janitor down the hall!” Les was looking for help finding someone to plow his driveway so he could leave home early the next morning. Jim told him, “If it can wait till midnight, another hour, I’ll swing over and do your driveway.”

Thinking nothing of it, Jim plowed the driveway and thought nothing more of it. About a week later, Jim got a call from Arlene Palmer, Les’ girlfriend, saying Les would like to see him.

Jim made the trip to Les’ house, where Arlene greeted him and led him to the kitchen. He recalls seeing “a little old man sitting behind the counter with a guitar. He looked up and said, ‘Howdy you must be Jim.’”

Les—not “Mr. Paul” as Jim quickly learned—greeted him with a smile, a handshake (using his left hand), and a thank-you. He wanted to offer something as payment. Jim insisted it wasn’t necessary, but Les was not one to take no for an answer. He went behind the counter and picked up a few cassette tapes. “This is my music and I want you to listen to it.” He asked Jim—who still had no clue who he was dealing with—“Do you play guitar?”

When Jim answered that he didn’t, Les decided to fix the problem: He handed him a thin, odd-shaped guitar with a little silver tube across its soundhole, then gave him a receipt with three chords—E, A, and D—scribbled on the back. He then demonstrated how to play the chords and told Jim to come back in a week.

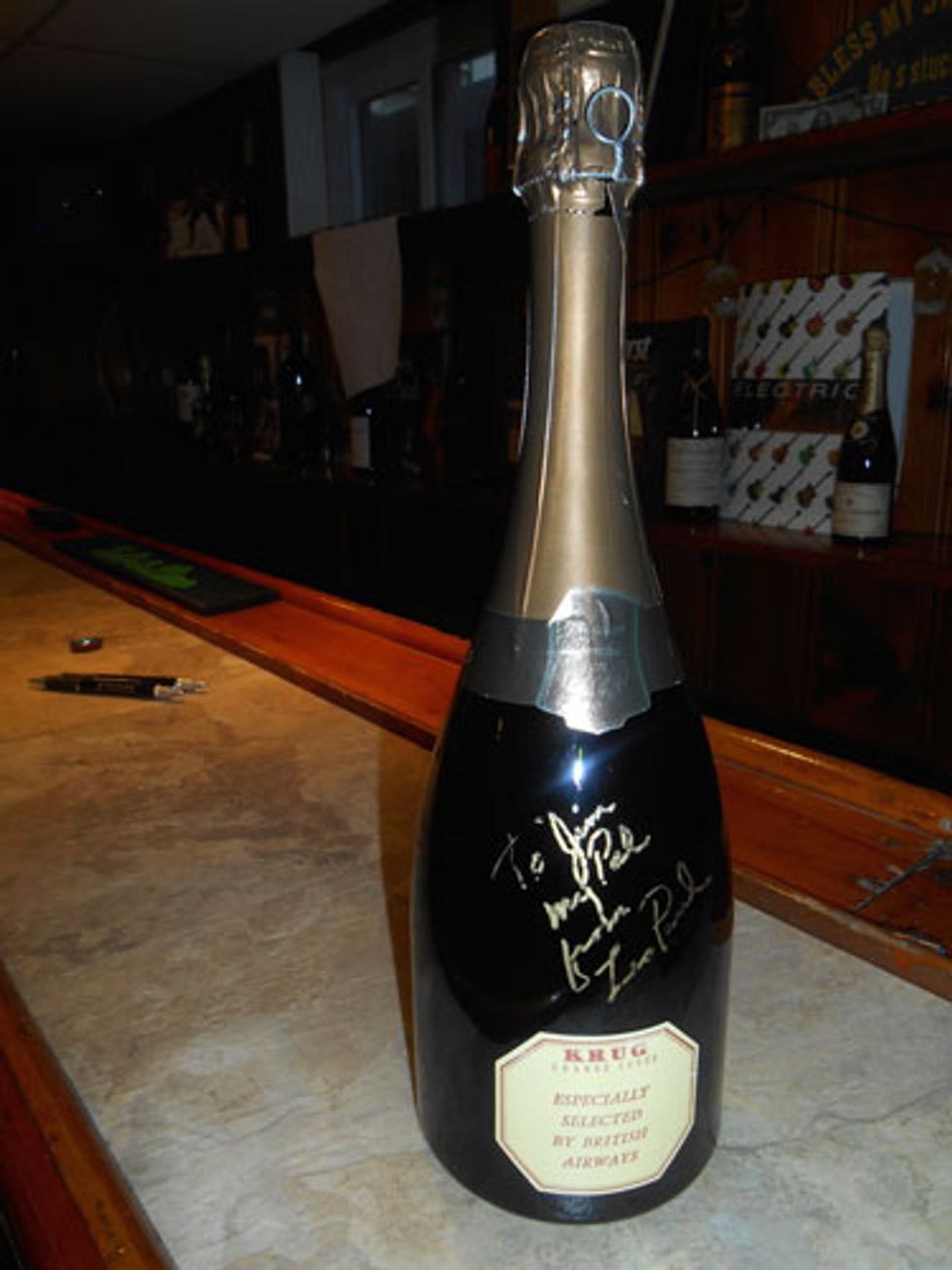

Before Jim left, Les gave him one other gift, a bottle of Krug champagne whose back label read, “Especially selected by British Airways.” On the front, Les had written in gold marker, “To my pal Jim, from Les Paul.”Les’ only request was that Jim save it for a special day.

When Jim asked about the bottle, Les’ answer was the first hint that he wasn’t dealing with just any elderly gentleman. “A bunch of years ago I got a phone call from the airline,” Jim remembers Les explaining. “They wanted me to go on a plane ride. They said everyone was going to go—Eric, Jeff, Paul.”

Perplexed, Jim asked, “Who?”

“You know—Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Paul McCartney.”

Needless to say, that got Jim’s attention. On his way home he stopped at the library, opened a few encyclopedias, and was shocked to see pictures of the man he’d just met.

When he went back the following week, the first thing Les said was, “Jimmy, did you learn those chords?” Jim bashed out the chords fast as he could, and Les said, “Good—[but] too fast. Slow down. Everything’s too fast.” He then took the guitar, went behind the counter, and turned his back on Jim, apparently busy with something.

While he waited for Les to finish what he was doing, Jim said, “I read about you—everything about you is Gibson. You designed their guitars back in the ’30s and ’40s, you were signed by them to endorse their guitars—so what’s with this Danny Electro guitar?”

“It’s pronounced ‘Dan-electro,’ Les corrected him. “Nathaniel Daniels, the owner of Danelectro, gave it to me as a present. It was a prototype, and I want to give it to you now … Put it under your bed for a rainy day.” When Jim said he couldn’t accept it, Les turned around, marker in hand, “It’s too late—because I already got your name on it.”

Watch an interview with Jim Wysocki:

It’s Not “Shit”—It’s Stuff

Les Paul was so famous that people were always giving him things—gifts, trinkets, gadgets. His house was full of them. Boxes, guitars, speakers, electronics, and all sorts of things were literally everywhere. “Three-hundred-sixty-five days a year he’d get something in the mail from somebody around the world,” says Jim, “and he would not throw it away. One day I asked him, ‘Hey, what are you doing with all this shit?’”

“It’s not shit,” Les replied. “It’s stuff, Jim. It’s stuff.”

Over time, Jim helped Les manage the build up of gifts in order to keep the house habitable. “One of the most interesting things I ever came across—I guess it was late in the ’80s—was an old, broken guitar sitting in a Seagram’s Seven box in a corner of Les’ basement.”

Les had called Jim and another friend over late one night to give him a hand fixing the furnace. As they were finishing up, Les asked Jim to bring the box over. “I told him it was junk,” remembers Jim. “But he said, ‘No, no. Bring it over.’” Jim retrieved the box and opened it. There was a dead mouse inside. “This right here,” said Les of the old Gibson archtop, “this breaks my heart. Do me a favor, take this guitar and do the right thing—put it under your bed for a rainy day when you fix it.”

It wasn’t until after Les had passed away that the proverbial “rainy day” finally arrived and Jim shipped the guitar to Gibson to have it restored. A year later the guitar was ready.

“I flew down to pick it up, and when they presented it to me I was expecting some brand-new guitar,” he recalls, “but here was this guitar that was rustic and old. It still had holes in the body—from bugs, as far as I could tell!”

The Gibson employees laughed at how appalled Jim looked. He clearly didn’t know how special the instrument was. “Turns out,” says Jim of the circa-1936 instrument, “it was one of Les Paul’s first attempts at an electric guitar. What I thought were bug holes actually turned out to be where he took a record-player needle and jammed it in the body.”

Jim took the guitar to vintage-guitar expert George Gruhn in Nashville to have it appraised and was laughed at yet again. He recalls George telling him, “You’ve got to be kidding me—I can’t even think about putting a price on this!”

Les’ Shocking Developments (Literally) As Jim understands it, Les’ interest in electronics started at a very early age. He says the guitar legend told him he was just five years old when he saw his brother Ralph flip a light switch and immediately wanted to know how and why the light turned on. “Back then you didn’t have breakers and you didn’t have safeguards on electrical lines,” says Jim. “As a result, Les was shocked many times—but he learned to respect it.”

Electricity apparently almost killed Les three times. The last incident occurred at his studio in 1941 when he was practicing with his bass player. With his guitar in one hand, Les reached into an audio stack and inadvertently touched a live wire.

“He fell to the ground and, at first, the bass player thought he was fooling around—because Les was a joker,” says Jim, “but when he noticed Les’ eyes start to flutter he realized something was really wrong and turned off the circuit.”

Les was so badly burned that the muscles were separated from the tendons in his right arm. The injury forced him to take a year off from playing, and during that time he found unusual new ways to study guitar. It was during that period that Les invented two of the world’s earliest solidbody electric-guitar prototypes, which are now known as “the Clunker” and “the Log.”

An Agreement Among Friends

One night in 2006 Jim received a phone call from Les asking if he and another friend who often helped around the house would come over. It wasn’t out of character for Les to call late at night, but it was unusual for Les to answer the door. Usually it was Arlene.

Les guided them through different rooms, pointing at various things and shaking his head. When they wound up in his guitar room, Les asked, “What do you think?” But Jim wasn’t sure what he was getting at and merely replied, “I don’t know.” Les told them to follow him downstairs, where they went out onto the patio and sat on a couch.

“I got a lot of pressure,” Jim remembers Les confiding. “A lot of people want a lot of my things, but I don’t want to give things to people that are just going to take them and go sell them for a yacht. So what are we going to do with this stuff?”

The other friend interrupted, “What do you mean, ‘we’?”

“You two have been a part of this with me for a long time. I need help. What are we going to do with all of it?”

Jim remembers the look on Les’ face—he was stressed. Genuinely worried. He and the other friend turned to Les and came up with a plan. “How about this deal: Everything you gave us over the course of 20, 25 years, we’re going to make sure people get to see, touch, and play after you pass away.”

Les reportedly looked at them, took his glasses off, smiled, and said, “That’s a deal—let’s go have a drink.”

Today, Jim is keeping his word on that agreement. “That’s why we travel around and we let people play his things,” he explains. “Some people think we’re nuts for letting just anyone touch these million-dollar guitars, but like Les always said, ‘It’s only a piece of wood. Gibson can fix it.’”For more information:

American Music Supply

Click here for more videos from American Musical Supply

Click here for more videos of Les Paul's historic guitars with Richie Castellano

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)