“We’d meet up in the morning,” says Satriani, ”and someone would say, ‘I really like that song, let’s do that one.’ And we’d spend a few hours learning it and arranging it, and then record it and that would be it. We’d move on to the next song.”

This mad dash proved to be a good thing and gave the album its fresh sound. “There’s a lot of spontaneity on this album because there wasn’t a lot of time to rehearse the songs,” says Anthony. “We would rehearse it 20, 30 times and then we recorded it.” The time constraints extend beyond the recording session. Because of Smith’s commitments, drummer Kenny Aronoff will be filling in for him on the band’s upcoming tour. But this won’t be a permanent lineup switch. Anthony says, “We didn’t want this to be a revolving-door band.”

The long road to Chickenfoot’s origin can be traced back to 1985 when Van Halen and vocalist David Lee Roth parted company. After this breakup, Roth did what any crafty jilted lover would do: He got sweet revenge. He recruited über-virtuoso Steve Vai along with bass hero Billy Sheehan to form a supergroup with superhuman, pyrotechnical abilities. Van Halen counteracted by bringing in Sammy Hagar as the new lead singer, but as Eddie Van Halen became more and more content to rest on his laurels, his position as the king of rock guitar was slowly being usurped by the continually innovative Vai, who ended up becoming the guitar hero to round out the ’80s and onward to the present day.

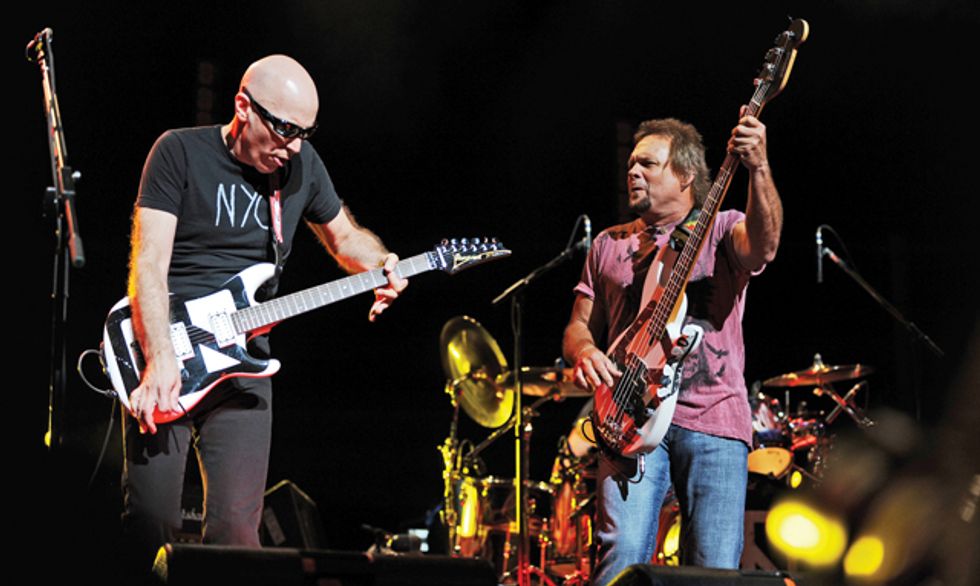

Flash forward to 2007 when the impossible happened and Van Halen reunited with Diamond Dave. This reunion came with a twist, however. Eddie’s teenage son, Wolfgang replaced founding member bassist Michael Anthony, leaving both Anthony and Hagar without a gig. They must have asked themselves “what would Dave do?” because soon after, they formed Chickenfoot, a supergroup featuring Joe Satriani—Vai’s former mentor—and Chad Smith from the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

This ensemble proved to be a success with Chickenfoot’s selftitled first album debuting at No. 3 on the Billboard Top 100 and going Gold. But this is no poor man’s Van Halen. “During the first tour we wanted to establish ourselves as Chickenfoot so we decided not to play any Van Halen or Chili Peppers stuff,” says Anthony. “Obviously some of the stuff is going to sound like Van Halen vocally because that’s where Sammy and I come from and people can identify with that sound in our voices. But we don’t want to be like Van Halen. We don’t want to be like the Chili Peppers, we don’t want to be like Joe’s solo stuff. We just do what we do.”

How did Chickenfoot III

come about?

Anthony: Because we were

going to be losing Chad to his

other band [laughs]. Actually,

we wanted Chad on the new

Chickenfoot record and we

knew once he got fired up with

the Chili Peppers that would

pretty much be impossible.

So we said, “Hey, let’s go into

the studio and put some stuff

together while Chad’s still free.”

Satriani: We always knew we’d

get together again and continue

it. After the set of tours that

we did, we really solidified as

a band and I think we all look

back on the first record like,

“Wow, that’s hardly representative

of what we can do.”

What revelations did you have?

Satriani: We felt like a band,

but we didn’t know if we

sounded like a band until we

had that first album. When we

hit the road we had to prove a

lot to ourselves. We went from

the club thing to the festival

tour and did the theaters and

the arenas in the summer and

then it was over. But in that

period we learned so much

about each other musically, and

the potential of the band would

really blossom every night that

we would play.

Anthony: I think we’ve really

niched out what Chickenfoot is

about on this record.

Michael, do you approach your

bass lines differently depending

on whether the guitarist is

playing more in the pocket and

bluesy or going crazy?

Anthony: The difference here is

when Eddie would go off, he’d

be like, “Pump on this note, it’s

king of like an AC/DC thing,”

whereas Joe gives me a chance

to play different things and not

just ride on one note.

Are you enjoying the freedom

you have now?

Anthony: Oh, it’s great. I don’t

think there was one time on

this album where Joe came up

to me and said, “Can you play

this here?” He let me go off

and develop my own bass parts.

Everybody was allowed to put

in their own two cents.

What differences and similarities

do you see in Joe and

Eddie’s approach?

Anthony: They’re both great

guitarists in their own right.

Eddie would treat every song

like it was an instrumental and

either Dave or Sammy or even

Gary would fit their vocals

around it. I had to be more

basic in my playing to really

hold it down.

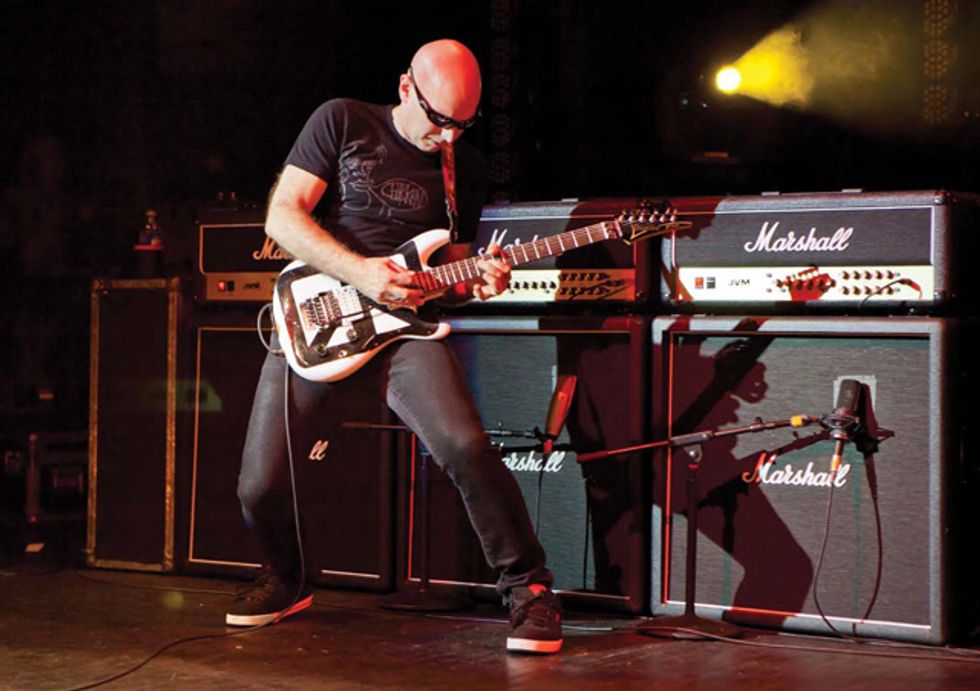

Joe Satriani’s Gearbox

Guitars

Ibanez JS prototype with DiMarzio pickups, Ibanez

JS2400, ’55 Gibson Les Paul, ’58 Fender Esquire, ’59

Gibson ES-335, Rickenbacker, Deering banjo, Ovation

12-string, Gibson Jimmy Page No. 1 Les Paul

Amps

Marshall JVM 410 Joe Satriani Signature Model, ’53

Fender Deluxe, ’59 Fender Twin

Effects

Electro-Harmonix POG, Vox Big Bad Wah, Vox Time

Machine, Voodoo Lab Proctavia, Roger Mayer Voodoo Vibe

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

D’Addario .010–.046, D’Addario .011 sets on some vintage

guitars, Planet Waves signature picks (heavy), Planet

Waves signature straps, Planet Waves cables

Joe, with this band, do you

feel Eddie’s shadow lingering

over the music?

Satriani: It was obvious that, at

least for me, I’m not going to

try and recreate the over-playing

heroics of the ’80s that was pioneered

really by Eddie. Nobody

can do it, really, like Eddie. So

why would you do it?

Anthony: I don’t want Joe to

do anything like Eddie Van

Halen or sound like him. We

get enough comparisons to Van

Halen the way it is [laughs].

People on the internet are like,

“Chickenfoot III...they’re jabbing

at Van Halen III.” I have

to laugh at these references—

they’ll make them musically,

too. I’m thinking, “Do these

people sit around all day long

and try to find one note that

Joe has in common with Eddie

and just go off on it?”

Joe, on this record you seem

to play less technically than

someone might expect, given

the band’s lineage.

Satriani: That can be said for

everybody in the band. Sammy

can try to sing higher than he

did with Van Halen, although

I can’t imagine trying to sing

higher than that [laughs]. Chad

can try to be funkier than he

is with the Chili Peppers and,

as you mentioned, I can try to

do flashier, more outside stuff,

but that’s so calculated and so

wrong to me. It’s the antithesis

of why we got together.

Anthony: Obviously, when you

have a lead singer, you don’t

have to be playing notes every

second. So now Joe doesn’t

have to play the melody and

everything all the time on the

guitar. I know he enjoys doing

all the rhythmic stuff, too, and

not just being the guy playing

the lead all the time. Maybe he

is making his own conscious

effort to kind of hold back on

the album. All I can say to that

is that people should come see

us live—Joe’s on fire.

Joe, your older stuff like Not

of this Earth is more cerebral,

whereas this is more feelgood,

jam music. Is it hard to

switch gears?

Satriani: No, it’s not. I know

that it seems odd from the

outside looking in. Twenty-four

hours in the day of Joe Satriani,

there are so many different

kinds of music running through

my head, and if I’m hanging

around at home I play lots of

different stuff. Stuff that you

would never release or you

wouldn’t want people to hear

because they wouldn’t know

what you were or what kind of

stylistic box to put you in.

But that’s typical for the way that a musician thinks. An artist is just simply being artistic, so when they see a mandolin, they start playing some mandolin music. Someone says, “Check out this piano,” they sit down and they play whatever piano music they know or like at that moment. We’re always hopping stylistic fences or at least, I should say, I am. I’m always playing lots of different things on an average day at home playing music. When you’re making an album you can’t do that. It’s very difficult to have a career based on being scattered stylistically.

But you’re the guy who

whipped rock guitarists of the

’80s into getting serious about

learning music theory and

studying the enigmatic scale

and pitch axis, among other

things, and now it’s back to

the basic blues scale. Isn’t that

quite a contrast?

Satriani: It is. That’s a really

good question you’re asking

and the answer is quite profound

for someone like me who

started out knowing absolutely

nothing and, little by little,

learning from very gifted and

patient teachers. What I’ve

arrived at, which is what all

musicians arrive at once they

get through all the learning, is

that a three-note scale doesn’t

carry any more extra weight

than a 12-note scale. Whether a

scale is called Lydian Dominant

or whether it’s called blues, it

doesn’t mean one is better than

the other.

A complicated arrangement is not necessarily better than a simple arrangement. It’s just music and what matters is whether it’s powerful—does it move people? Does it move you, the artist? So it’s really great when you arrive at that point and generally you can’t, until you actually know all of it. I’ve been as good a student as I can possibly be all these years. So I can say, “Yeah, I can play harmonic minor scales harmonized in any way that you want, in any key, anywhere on the guitar.” None of that phases me anymore. So that means that everything’s equal. I’m not impressed by complications.

Joe, Chickenfoot’s music is

definitely less complex than

a lot of your own music. No

adjustment issues?

Satriani: Well, Sammy’s always

dogging me about two things.

He wants me just to go crazy.

He doesn’t want me to work

things out, and he’s always trying

to convince me that commercial

success is a good thing.

My success is based on being

under the radar, so it’s natural

for me to go for the odd, not

the accessible. The joke in the

band is that whenever we’re

working on a song that we

think might have some commercial

success, it’s guaranteed

to put me in a bad mood and

I’ll want to stop working on it.

“Different Devil” comes to

mind as one with a commercial

sound.

Satriani: I think the worst

mood I was ever in with

Chickenfoot was when we

recorded that song. When I

brought the song in it was

about 90-percent finished and

I thought it could be a really

good and weird song—the

typical way I think of things. I

bring it in and everybody starts

tidying it up, and then I start

to think, “Hey, it sounds like

you guys want to make this an

accessible piece of music.” And

I’m bumming out about it.

Later Chad took my acoustic guitar back to the hotel room. He shows up the next morning with a new part to the song and Sammy hears it and says, “I could sing a chorus over that.” So we insert it into the arrangement, and after awhile I’m going, “They’re right, this is actually sounding pretty good.” And so we built up the track until the end of the day. Then over the next couple of weeks as we’re doing the overdubs, I started to realize that the melody Sammy’s singing doesn’t actually go with the chords that Chad wrote for the chorus part. So I had to go and listen to Sammy’s vocals without guitars and bass, and figure out melodically what he thought he was singing over harmonically. Once I realized what he was singing over in his mind, I had to go find those chords.

Did the reharmonized version

throw him off?

Satriani: No, it fit because

I think when we did the last

tracking together everyone was

just worried about their parts,

they really weren’t thinking

about what Sammy was singing,

they figured he’d change

his vocals. But I know Sammy

and when Sammy gets on a

trajectory he’s not going to

change his vocals. He’s going

to look at me and say, “Joe,

change those chords.”

“Come Closer” showcases a

moodier side of the band.

Anthony: That’s a song where

Sammy already had the vocals

and lyrics first.

Satriani: One morning I just

went over to my piano and

put the cup of coffee on

one end and the iPhone on

the other side and I very

quietly sang a moody… it

was sort of like, if you can

imagine, Radiohead doing

an R&B song. It was kind of

drifty, especially in my croaky

voice. I quickly emailed it

to Sammy to see if this was

something he could get into

because this was me putting

him in a lower register.

Was that one originally written

on the piano in A♭ minor

(as it sounds) or A minor but

then played tuned down?

Satriani: It was written in

A minor. I’m not too good

with A♭ minor [laughs]. I play

just enough piano to get a

song across.

Michael Anthony’s Gearbox

Basses

Yamaha BB300MA Michael Anthony signature bass

Amps

Ampeg B-50R

Effects

MXR Micro Chorus (live only), MXR Blue Box (live)

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Dunlop picks, Jim Dunlop strings (.045, .065, .087,

.107), Monster Cable (studio), Shure wireless (live)

Joe, in your “Come Closer”

solo, you play this long arpeggiated

sequence then in the

last two measures you break

away from it so it doesn’t

sound predictable.

Satriani: Right, I had to let

loose. To tell you the truth,

when we were rehearsing, it

had a loaded bluesy solo in the

beginning, and I just started

thinking that it sounded too

much like a power ballad where

the guitar player steps up and

he’s blowing a solo on the

mountain top. I thought that

was too corny. I kept thinking

with the solo that I wanted to

be part of the band.

Let’s talk gear for a second.

Joe, I understand on this

record you used that blue

Ibanez prototype with three

single-coils you played on the

Experience Hendrix tour.

Satriani: Yeah, that prototype

is a winner, man. We’ve worked

on that one for almost 10

years now and Steve Blucher

at DiMarzio just came up with

really cool pickups that, for

some reason, really go together

with a maple neck and that

particular body. It just sounds

like the punchiest Strat you ever

heard in your life.

Is this the first album you

recorded with this guitar?

Satriani: I think it is. And

the whole record was done

primarily on my new 4-channel

Marshall signature amp

called the JVM 410 Joe Satriani

Signature Model.

Michael, I know you generally

use your Yamaha signature

bass, but what happened to

the Jack Daniel’s bass?

Anthony: I still have it and

it will probably come out on

tour. At the end of every tour,

I put it in the closet and say

I’m done with it. And there’s

always somebody like you who

says, “Hey, what’s with the Jack

Daniel’s bass?” My original one

has been on display for at least

a couple of years now at the

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

in Cleveland.

Michael, there’s a rumor that

you’re the richest among the

original Van Halen members,

is that true?

Anthony: [Laughs.] Well, everybody

used to joke that I saved

the first dollar that I ever made

in Van Halen. I probably did

somewhere. You know what,

my wife Sue and I, we just celebrated

our 30th wedding anniversary

in February. That might

have something to do with it,

because every guy in Van Halen

is divorced—a couple of them

a couple of times. So, of course,

that’s going to tax their account

a little bit.

Some people out there say

Chickenfoot is in it just for

the money, but you guys don’t

really need the money. Sammy

made something like 80 million

dollars selling a share of

his tequila business.

Anthony: And that was just

selling the first 80 percent.

Once he sold the last 20 percent,

I’m sure he made a good

penny on that, too. The best

part about Chickenfoot is that

nobody needs the money. We’ve

got nothing we need to prove

to anybody. We wanted this to

be a fun band and when we get

in the studio it’s just so loose,

relaxed, and open. It’s like

the early days of Van Halen.

Everybody’s just throwing in

their input and having a great

time making music. We don’t

want any pressure and we said

if any came up, we should just

stop doing this.

Michael, if the situation presented

itself, would you rejoin

Van Halen?

Anthony: At this point in my

life and career, I’m so happy with

what I’m doing and I want to

have fun making music. I don’t

want any drama. That whole

drama thing in Van Halen, the

way it ended up, I was like, “I’d

rather make no money having

fun playing music than make a

shitload of money tearing my

hair out.” Maybe when I was 20

it would have been different, but

not at this point. I want to keep

my sanity.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.