“When you have someone else making macro decisions, it frees your brain up to address the smaller things,” attests Jesse F. Keeler, bassist for Canadian dance-punk duo Death from Above [DFA]. Keeler is referencing the pile of songs he and his bandmate, singer/drummer Sebastien Grainger, had written prior to recording their latest gut-punching opus, Outrage! Is Now. When they got together with producer Eric Valentine, they just “dumped everything on him” and let him make the executive decisions about what they would work on. “I’m glad we did do that,” Keeler adds. “It ended up being an album because he had more perspective than we did at that point.”

Toronto-based DFA formed on September 11, 2001, in response to the events of that day (more on that later) and released their debut EP, Heads Up!, in December 2002. In 2004, they changed their name to Death from Above 1979 in response to a cease-and-desist issued by DFA Records, and released You’re a Woman, I’m a Machine under that new moniker. Balancing what Pitchfork called “riff-heavy micro-Sabbath bravado with tenderness,” the album, with songs like “Sexy Results,” was a hallmark for the dance-punk genre. But the overt bombast with which DFA wrote and performed underscored the tension that existed between Keeler and Grainger and, despite their success, the duo disbanded in 2006, citing creative differences. They reformed in 2011, performing at Coachella in Indio, California, alongside other luminaries, including the Strokes and Duran Duran, and have remained together, releasing their second full-length, The Physical World, in September 2014.

Outrage!, which came out in September sans “1979” in the band’s moniker, reveals a new level of maturation for the duo. Pre-production commenced at the end of 2016 and they started recording in January 2017.

“We would dive into certain songs and feel like, ‘We’re not going to beat that sound, but let’s try,’” admits Keeler. “We’d been demoing separately and together for over a year. Some of the songs, like ‘Never Swim Alone,’ I wrote in the winter of 2015. We really planned this session. It’s the most forethought ever put into making a record for us, so it was smooth and quick.”

Premier Guitar caught up with Keeler, who was at home in Toronto doing press for Outrage! and preparing for one-off gigs, like Riot Fest in Chicago and Osheaga Festival Musique et Arts in Montreal, to discuss, among other things, the history of his relationship to the bass guitar, the formation of DFA, his recording techniques, tuning down his Dan Armstrong Plexi basses, and his resilient, vintage gear.

You’ve had some time to live with the songs on Outrage! Is Now since you recorded it. Has your relationship to the album shifted in any unexpected ways?

I listen to it now and think about the best ways to accomplish everything on the record, live. In the studio, I just spend time figuring out every pedal combination to get sounds exactly right, but it’s not like I’m not going to have a guy kneeling in front of a pedal or holding it in his lap adjusting while I’m playing, so how do I approximate what I did, live? Listening to the song “Outrage! Is Now,” for example, I’m thinking about the synth sound and whether I’ve already nailed it and how I can mess with it live when it’s being performed. I feel like I’m still listening to it with those ears.

Is making a record an enjoyable experience for you?

Yes, but in terms of what the songs are, live is where it’s the most enjoyable for me, because that’s where it all comes together. I get to improvise every single time we play the songs. As soon as I started to become comfortable improvising onstage, that’s when I started to love being on tour. I didn’t have to stop being creative just because I was on the road. I could continue to be creative and not just perform something that was already complete.

How far do your improvisations push the song structures?

It’s not like I’m rewriting the songs every day. But just knowing if I’ve got an idea, I can do it. I don’t have to hold back. I’m not trying to replicate the recording. I’m trying to make that moment be the best it can be. That was very liberating for me. It’s been 23 years of playing in front of people. Understanding that I could be just as creative is something I only caught in the last couple of years really.

Your musical journey started on drums, correct?

I started playing drums when I was 3, and that’s because my dad is an incredible guitar player, so I didn’t want to touch a guitar. Well, I did want to touch a guitar, but when he would play, it was so intimidating. When you’re learning an E chord and the person in front of you is playing so effortlessly, it’s incredible—it’s so fucking far away. It’s so far away, it’s like you’re an ant looking at the moon through a cloud. So, I didn’t want to do that. We lived in a house with people from Alice Cooper’s band at the time, including guitarist Prakash John, and there was a drum kit there, so I started playing drums.

TIDBIT: Listen to “Moonlight” on the Death from Above’s latest album to hear how Keeler uses the EarthQuaker Bit Commander pedal to create booming bottom end while he plays high on the fretboard.

Do you still play the drums?

Drums are still, for me, the instrument where I feel the most immediate in terms of the distance between my brain and what I’m hearing. It’s the shortest. I can execute what I hear almost immediately. I do feel like I’m getting closer with the bass. Occasionally, I have an idea and I just play it instantly and afterwards think, “Whoa, I can do that now. I’ve been playing bass long enough.”

You eventually did pick up the guitar. When did you pick up the bass?

When I was a teenager, I started playing guitar and then just continued playing guitar or drums in bands. The relationship with the bass was always sort of something I would do at the end of a recording. I would think, “Oh, I have to add some bass. So, where’s a bass?” and borrow someone’s bass and track it and just really treat it like a low guitar. I did what I think tons of rock bass players probably do: just play along with the guitar and maybe make a modulation underneath. You know, bass [laughs].

Was there a defining moment for you when bass finally became your primary instrument?

The day I started this band, on September 11, 2001, there was a Squier Jazz bass someone had left in our house. I picked it up because everything else was in a case. I just started making up songs. I can’t tell you why, other than that I needed to do something with my hands. Our old band was supposed to go play in Detroit the next day, but considering all the things happening in the world, all shows were cancelled and they locked everything down. All the borders were closed. So, we were like, “I guess we brought all the gear up out of the basement for nothing.” And I just started plugging stuff in and made up this bass sound I’m still using today. It’s essentially the same signal path from that day. Cabinets have changed, speakers have changed, the bass has changed, but the essential setup is still there.

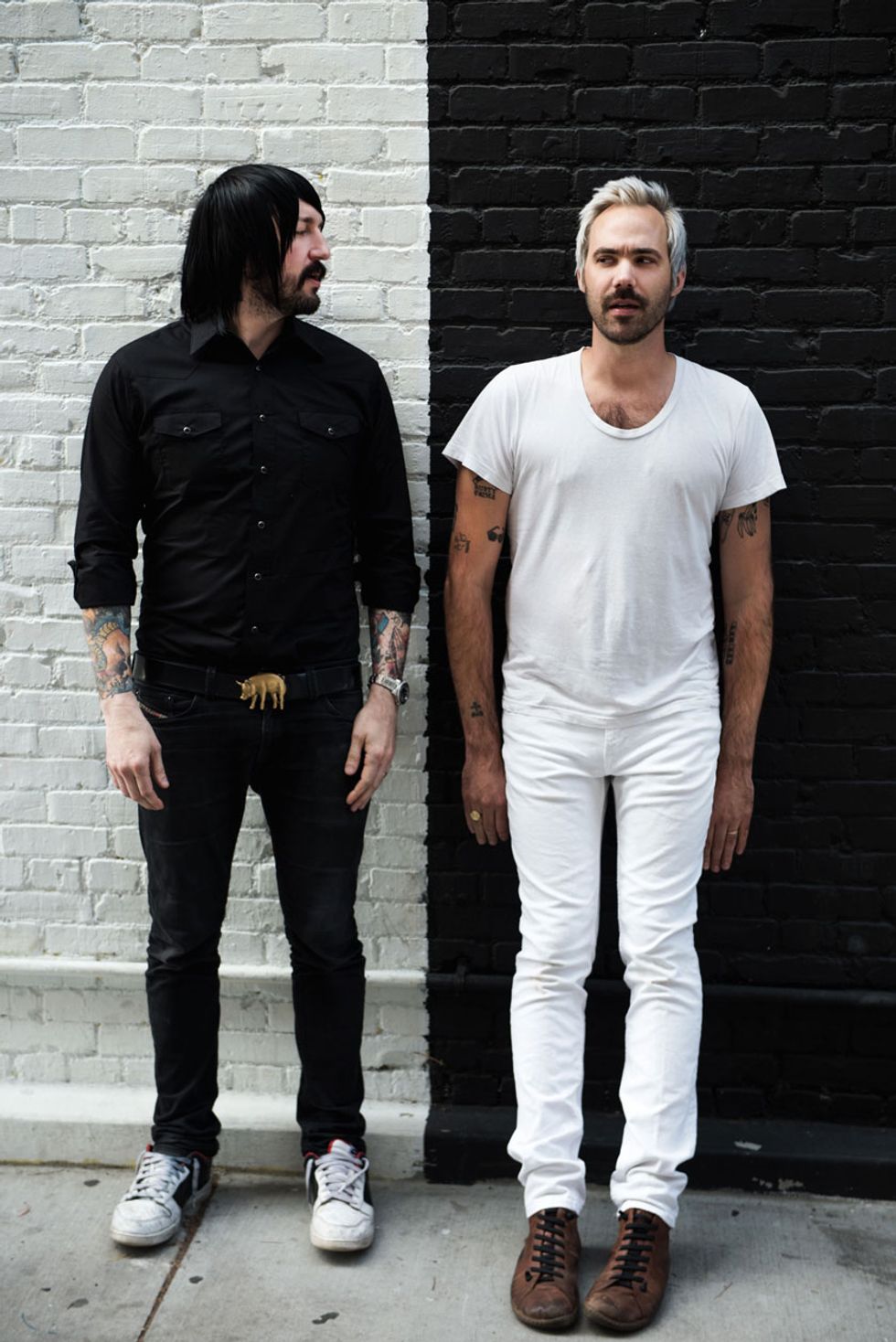

Live, Keeler and singer/drummer Sebastien Grainger create an astonishing variety of sounds for a duo, spaying their grooves with expressionist bass and unpredictable—and often guitar-like—blasts of synthesizer.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

When you were writing back then, did you think you’d have a more traditional band configuration to play your songs?

I wrote three songs and showed them to Seb under the guise of, “We can play guitar over this.” And one day he came to me and said, “Why don’t I just sing and play drums at the same time?” So, we went downstairs to try it. He pulled a mic over to the drums, we played one song, and looked at each other like, “Oh, it worked! That was actually pretty cool.” And that brings me to today [laughs].

Has your relationship to the bass changed since then?

My relationship with the bass as my instrument has only existed from the day that I was trying to write songs on it. That was basically it. That’s still the core of my approach. I like the restriction of having just four strings. People say, “You could have five strings or six strings or use something else.” The Dan Armstrong has 24 frets. I’m happy with that many octaves and it’s comfortable for me to play. I’m just trying to write songs, really.

Speaking of the Dan Armstrong Plexi bass, that wasn’t your first bass, was it?

I feel like the Dan Armstrong is an instrument that, when you’re a kid, you see it at some point and you’re like, “Wow, that’s so cool,” and then you never actually hold one [laughs]. You know what I mean? No one actually has one.

we play the songs.”

The first bass I bought was a ’74 Gibson Grabber, which is full scale, incredibly neck-heavy. You use half your left arm strength just holding the thing up. There’s no way to harness that so it doesn’t fall over on you all the time. But the pickup was really hot and it sounded really good and I bet if I picked it up right now after not picking it up for years, it would be perfectly in tune. It’s just the way that bass was.

Why did you switch to the Dan Armstrong?

I wanted something else because we started playing bigger shows and being on the road for longer and longer periods of time, and I thought I should probably get another bass. So, I went into a music store and there was a Dan Armstrong. I tried it and thought it felt weird and wrong. The 12th fret, when you’re holding it on your body, is like where the 22nd fret is on the Grabber. Just trying to move over to it felt foreign. It felt like a toy, but I bought it anyway because I thought it would be cool to have two octaves to play around with.

But you only really started using it in the last four or five years?

That’s because I took it home, re-strung it—we had a show the next day—went to the show and, when I was tuning it up, one of the tuning pegs just snapped in half. I already thought it seemed sort of delicate with the little rosewood bridge, but when that happened I was like, “Fuck, this thing is not roadworthy. If I bring this out and that happens, I’m screwed.” I took it back to the store and they offered to straight trade it for something that was the same price. So, I tried this ’75 or ’77 Rickenbacker 4001 and liked how it sounded, even though it sounded a bit thin compared to the Grabber, but I took it, played that for years, and now I seem to be known for playing the Ric.

Basses

1969 Ampeg Dan Armstrong Plexi with Kent Armstrong custom pickups

Amps

Peavey Super Festival F-800B

Acoustic 450B

Two Traynor YC-810 Big B cabs

Eminence PA speakers (10”)

Peavey Delta Blues (10”)

Effects

Death By Audio Echo Dream 2

Dunlop KFKQZ1 Kerry King Limited Edition Q Zone

EarthQuaker Devices Dispatch Master V2 delay and reverb

EarthQuaker Devices Bit Commander octave synth

Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

Ernie Ball 6185 Wah

Ibanez CS9 Stereo Chorus

Morley ABY switcher

MXR Carbon Copy

MXR M80 Bass D.I.+

MXR M108 10 Band EQ

Palmer PDI09

Roland Juno-60 synthesizer

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball 2832 Regular Slinky Roundwound (.050–.105)

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm

What made you switch exclusively to the Dan Armstrong?

When we started working on the last record, as we were writing, very early on, I thought, “You know what? I’m going to try that bass again.” So, I tracked one down. Friends at Chicago Music Exchange put the feelers out and found one for me. That first one that I got is still my main bass. I’ve got four of them now. But that first one is just magic. From the day I got it, I started writing. You know how it is when you have a new instrument: Sometimes it’s just a flood of creativity as you get to know it. Interestingly though, it hasn’t stopped for me with that bass. I’ve been playing them now for four or five years and I still feel like I’m learning things about them. They’re all very different.

What’s different about them?

I learned from someone who worked there that they were making the necks by hand. I was scared about short scale not being deep enough, but that’s not a problem. I was worried about keeping the intonation in over the whole neck, but I had this luthier design a bridge for the bass so it would have individual string height and intonation, so that’s not an issue anymore. He machined it entirely from a chunk of aluminum and put brass seats on all of them.

Who was the luthier?

Les Godfrey [of Toronto’s Godfrey Guitars] designed the bridge so that it would use the exact same mounting holes and the same screws, because you really can’t screw in and out of Lucite a bunch of times. Once the grooves are there, you want to stick with them. And so, he’s made me three of them and I have one bass that has the original bridge and that’s my “home” bass. It doesn’t come on the road.

What about the pickups?

Kent Armstrong, Dan Armstrong’s son, is out there in Vermont making pickups, and although he doesn’t have them on his website, I reached out and asked if he could make pickups for his dad’s old bass. He’s made me about six so far. I’ve got some single coils—we tried different magnets: single, double. I think this is it for me. I’m happy with this bass. When I hold it in my hands, the distance from my brain to what you hear coming out of the speakers is the shortest it’s ever been.

When writing, are you influenced by drum grooves? How do you go about crafting your parts?

Generally, I’ll have some sort of melody or riff idea and most often it’ll be when I don’t have a bass in my hands, so I’ll grab my phone and turn on the voice note recorder and hum it in. If anyone ever stole my phone there would be albums of humming and humming [laughs]. Sometimes I’ll tap the phone to give myself a meter, tapping the mic like a kick drum. Then I’ll get a bass and figure out what I hummed. Sometimes I go through voice notes and find the same idea keeps popping up and I’ll go, “Wow, I guess I really like this idea,” because I keep rewriting it [laughs].

At September 2017’s Riot Fest in Chicago’s Douglas Park, Keeler digs his .73 mm pick into the strings of one of his four vintage Ampeg Dan Armstrong Plexi basses. “The Dan Armstrong has 24 frets,” he says. “I’m happy with that many octaves and it’s comfortable for me to play.” Photo by Perry Bean

Do you overdub bass parts? Sometimes I feel like I’m hearing multiple parts.

I’ll always do an overdub, but it’s just a double. I just play the same parts again. Mainly because I don’t want to go out live and have these harmonies that I can’t accomplish. If there’s a harmony idea that I have, I’ll write it as a synth part that Sebastien can trigger from his sampler. There are instances where you’ll hear a synthesizer part just running and I’m playing along with that or it’s a part that comes in and out. If the synth is being sent through the same signal path as the bass, they start to become indistinguishable. That’s the only trickery: me using my other instrument as well.

Do you have any current go-to effects?

The one effect I don’t know how I lived without, because it’s the greatest thing ever, is the Death By Audio Echo Dream 2, which is on almost every song on the record—and if it’s not on the bass, we used it on the vocals. They threw a fuzz in there as well, which is incredible by itself. I’ve been using it with MSTRKRFT [his electronic duo with Al-P] as well. I’ll run drum machines through it, synths, everything. It’s a magic pedal.

It sounds like you’re experimenting with more reverb nowadays.

Yeah, it’s an EarthQuaker Devices Dispatch Master, which is like a reverb that has an echo in it as well. I never used ’verbs before. I wanted to. We’d play with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and that dude has so much ’verb on everything. I wanted to do that, too, but every time I tried it would just feedback all to hell. It was gross [laughs]. So, I never did it. But then on this record, Eric basically showed me the problem was that I was putting the reverb at the wrong point in my chain. I was putting it at the beginning and he told me that if I put it at the end, right before the amps, that wouldn’t happen. The ’verb was basically going through a chorus and everything else. It ended up being too unwieldy.

There are a couple of songs on the record where there’s a synth-sounding thing, but it sounds like bass to me.

Yes, I’m using an EarthQuaker Bit Commander, which is like a synth thing, but I only use it when I’m playing up high on the neck so the parts don’t lose the bottom. One thing Eric really impressed on me was, “When you’re playing these parts and these riffs, we can’t neglect the low end, so let’s find ways of keeping the low end with pedals.” The whole chorus of “Moonlight” is up at the 20-something fret on the F-string, but I’ve got the Bit Commander pulling the bottom two or three octaves below to keep it solid. The sustain on it is so insane. It’s fun to play with.

Since you mention your high F-string, can you talk about when or why you decided to tune down a whole step?

I started playing guitar like that when I was 17 or 18, and initially it wasn’t some deep meaningful thing. I had the guitar tuned to drop tuning, which I didn’t like, but instead of tuning the guitar back up, I tuned down to the D. I really liked how having less tension on the strings made it fun to play. I liked how the strings reacted, depending on how hard you pressed on them. When they’re that much looser sometimes you can just press on a string and that can be a bend. My brain really likes creating in keys where those open strings work. Half the DFA songs are in G or C or F. There are open strings all over the place on all the songs. My brain is just happy creating with those.

Let’s talk amps. You obviously prefer solid-state heads.

I remember when I was a kid asking my dad about tubes and solid-state stuff, because he really liked solid state-stuff, and what he said was, “The attack on the solid-state is always going to be more immediate than the tube. Maybe it’ll be infinitesimal, but you’ll notice it.” And that’s been my experience. There’s no mush on the solid-state amp—even with a ridiculous amount of distortion it’s still very instantaneous. And the way I play and the way the songs are, I need it. Before we could afford to bring our amps on tour with us, I used SVTs and tried to recreate the sound the best I could with pedals. I didn’t dislike it, but I found the character was different.

Have you ever tried to reverse engineer the Peavey Super Festivals to clone them?

I’ve spent thousands of dollars doing that just to have the result not be right. I talked to the people at Peavey. I found out the whole history. The guy was hired from RCA or Zenith, so he was making amps with TV components because that’s how he was comfortable designing. Even when I’ve tried to go one-to-one matching all the caps—the old and new values are supposed to be the same, but you scope them and see how different the rise and fall and response is on some of these components. I’m trying my best, but I guess I just have to keep these old guys because they’ve been doing their job. So, I just buy them when I find them on the road.

How do you record your bass?

I record a DI signal, using the MXR M80 Bass D.I.+, and what I’m sending through that is just probably 200 Hz and lower. It might even be lower, but it’s just sub information. And then afterwards we’ll screw around and run an octaver on it. There are a lot of songs where the whole song might be above the 12th fret, so having the octaver on the DI helps keep it as actual bass. And then I mic the cabs. We mic them at a distance rather than close-miking one cone, which isn’t really what it sounds like to stand in front of 8x10s anyway. We mic them about 2 feet back or so and put them in an isolation room and leave the door open and then have some mikes out in the room to catch the room sound.

Any pieces of gear or secret weapons that have changed your life?

Palmer DIs. This tech for the Deftones, named Drew Foppe, gave them to me at the end of a tour and I guess he got them from Fleetwood Mac, who he also works for. It’s the PDI 09—little DI boxes that you put between the head and the cabinet. Even though my amps are very powerful, I never have the volume up very loud. I just don’t need to. I guess the signal is not too hot for these little DIs. So, the combination of the mics in front of the cabs, mics outside the room, the DI, and these cab DIs is pretty much how I recorded everything.

Do you run your sound the same way live?

Live we don’t mic cabs anymore. I just use the Palmer DIs. I don’t know if this is an old wives’ tech tale, but apparently when the speakers are moving the negative motion sends some sort of resistance back into the speaker cable and somehow these Palmer DIs pick that up and apply that. I don’t know if that’s what’s happening, but the DIs are passive and whatever they’re doing, they sound amazing.

You play exclusively with a pick?

Tortex .73 mm big triangle, and I’ve been using that forever. I’ve tried using other picks, and when I’m playing by myself I’ll play with my fingers because it’s just fun and it’s a different way of being fast. My bass influences, in terms of bass players, that I really liked from when I was a kid, were Larry Graham and Chris Squire. As I got older, I learned that they both played Rics and they both played with a pick. I like the harmonic control. I know how to use a pick, so I feel the most comfortable working that way. And, just from playing guitar for so many years, it seemed like that’s how I want to play—although, I play guitar with my fingers [laughs].

Onstage in July 2017, Death from Above claw into “Freeze Me” from Outrage! Is Now. Note Jesse F. Keeler’s guitaristic approach on his Dan Armstrong Ampeg bass as he kicks into a gnarly solo a bit after the 2-minute mark.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)