Guitarist/loop-master Dustin Wong likes to keep it simple, although that isn’t obvious at first glance. His music is an intricate fabric of complex interlocking rhythms, multiple looped layers, and subtle timbral contrasts. But simplicity is his music’s dominant feature, which explains its accessibility and tunefulness, as well as its swirling, repetitive, mantra-like feel.

Simplicity also explains Wong’s penchant for low-tech gear.

Wong relies on a handful of off-the-shelf pedals—mostly Boss, and with only one mod—and an inexpensive guitar to craft his futuristic, multilayered music. He takes his time learning each effect’s inner workings and limits his purchases to about two a year.

Wong first garnered attention as one of two guitarists in the Baltimore-based, experimental pop group, Ponytail. Ponytail was a band hell-bent on positivity and pushing the artistic envelope. It was also a band—like Talking Heads and A Place to Bury Strangers—that was formed in art school. “I went to the Maryland Institute College of Art,” Wong says. “I studied sculpture, performance, and stuff like that. Willy [Siegel]—she sang for the band—developed her own language. She would chant along with the music. But music was more of a hobby when I was in college.”

But that hobby took over and music became Wong’s primary focus. He left Ponytail in 2011 and released several critically acclaimed solo projects. Those albums chart his development as an original voice in contemporary guitar. They also demonstrate his unique spin on looping, tone generation, and delay manipulation.

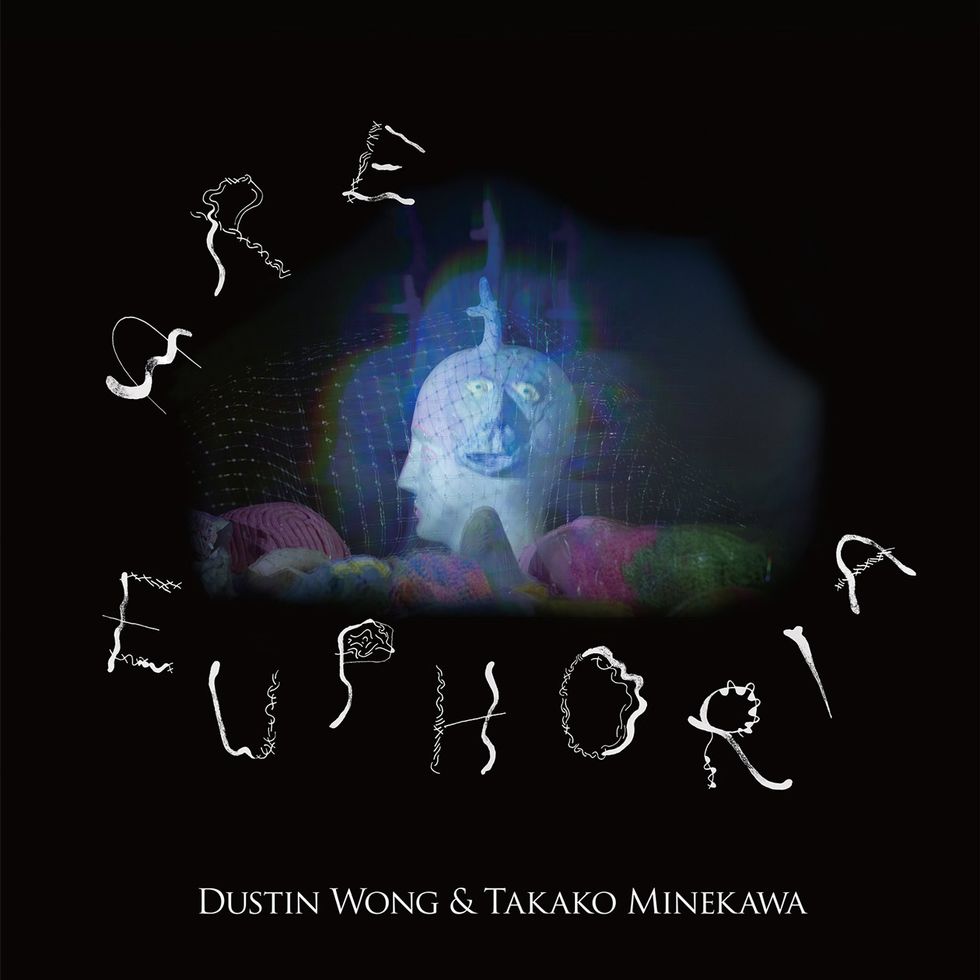

In addition to his solo work, Wong began a collaboration with the Shibuya-kei artist Takako Minekawa, who sings and plays keyboard. Their third release, Are Euphoria, came out in June. It’s an obvious addition to his canon and weaves a complex fabric that—at least at first glance—seems simple. It’s like a kaleidoscope, but minus the psychedelics.

Premier Guitar reached Wong at his home in Japan via Skype. He spoke at length about his use and choice of effects, his composition and collaborative process, different ways to tease rhythmic figures from synced delay pedals, and why—after a string of not-so-happy accidents—he almost never uses an amp.

When did you start playing guitar?

I started playing guitar at a fairly normal age, like 14 or 15 years old. My dad was a real classic-rock fan—this was during the ’90s and he was rebuying his favorite records on CD—and his favorite artist was Frank Zappa. Zappa became huge for me. I would listen to a bunch of his albums in middle school—Hot Rats, The Grand Wazoo, Apostrophe ('). Of course, I started with The Best of Frank Zappa and then it unfolded. On that album, I think my favorite song was “Peaches en Regalia.” That’s how I got into Hot Rats. And then Beefheart.

Anyone cool has gone through a Beefheart phase.

[Laughs.] If you keep listening to music you run into him eventually.

How did you get into pedals and loopers?

When I began playing in a band. Before Ponytail, I was in a guitar duo [Ecstatic Sunshine] and back then we’d only use the footswitch to turn on the different channels of the amp. But then it started with one pedal, like, “We should get a delay pedal.” And then it was, “We don’t have enough low end, maybe I should get an octave pedal.” When forming Ponytail, towards the end I had five pedals—octave, distortion, envelope filter, two delay pedals—plus the looper. With the band, I would switch off different pedals sequentially, but with the looper, I would play by myself and think, “Oh, I can change settings on the pedals while I am looping. Or while the loop is going I can shift the octave pedal to a higher octave or a higher gain distortion. Or I can even change the delay settings.” It opened up a lot of options when I was working with the loops. That’s how I really started figuring out how to use pedals.

Looping artists are often loners, but you’ve done a lot of collaborations. How does looping work with a band? Do you drive your drummers crazy?

I think about that a lot. There is weird lingo with music equipment, like how when you’re syncing up MIDI, there is, “This is the master. This is the slave.” When I’m dealing with loops, I think, “I am enslaving the drummer.” That’s how I feel sometimes. When I play with a drummer I try not to do rhythmic loops. Instead, I try to do loops that are more flexible for the drummer so that it will be easier to collaborate.

Do you do more textual soundscapes and that type of thing?

Yes. It could be a drone. It could be percussive, but not rhythmic.

What are the advantages or disadvantages of working solo versus working with a band?

I love working in a band so much. It’s a lot more spontaneous. You can wait. You don’t have to play all the time. You can let the band unfold, as in, “I can come in now or I don’t have to play at all.” It gives you that breathing room in a band setting, especially if it’s improvised or it’s a jam.

In your current collaboration with Takako Minekawa, how much of that is composed and how much is improvised?

The songwriting is very improvised. When we’re making the songs, it’s all free flow. What we do is we record it, memorize everything, and then perform it—and at that point it’s completely composed. The way you hear the record—the songs—that’s the pace, how we perform it in a live setting. Once I place one melody, I’m getting ready for the next one. It’s very [snaps fingers], you have to be on it.

Of course, there are little subtle changes, “Maybe I’ll try this one part different.” There is a little bit of flexibility, but it’s mostly composed with the two of us.

But when you’re writing, anything goes?

Right. We start with a melody or a rhythm that we both think, “That’s interesting.” We keep that loop going and we jam on that for a while. Then, if we find something interesting that goes on top, we loop that and then jam more. We might jam for half an hour to figure out maybe half the song. Then we start over, go forward, refine.

Your composition process is more like editing.

Yeah. We’ll record it and there might be some unnecessary sounds that are butting heads. “That frequency is already taken. I don’t have to play that part on guitar.” So I won’t play it. I’ll cut the fat out.

For Are Euphoria, Wong created hypnotic layers of sound using only his Telecaster, a looper, two digital delays, and a few other pedals.

For someone who does as much looping as you do, you use the Boss RC-2, which is a very old-school looper.

I graduated recently. I got the TC Electronic Ditto Looper X2. I normally buy pedals infrequently, maybe two per year. That’s my limit right now, because then I get to really learn the pedals. It’s better.

What was the reason for your upgrade?

I was recording albums with the RC-2 and the bit rate and sample rate is fairly low. It’s 16-bit, 44.1 kHz, which is CD quality, but when you want to record at higher quality, it’s compromised. If you’re recording at a 96 kHz sample rate, since the looper is 16-bit, it doesn’t really translate well. So I wanted higher quality and the X2 is 24-bit.

The X2 also doesn’t have the drum patches like the RC-2.

Yeah. Sometimes my fingers might slip and the drum track comes on in the middle of the set. [Laughs.]

The RC-2 also doesn’t have a stop setting. How did you work around the double click to turn it off while keeping time?

There is a stop setting on the Ditto X2, but you also have to hit it twice if it’s not in the stop setting. I figured out how to stop it on the RC-2 and it became second nature to me after a while. You count “one, two, three, four,” hit the pedal on “four,” and then hit it again. It’s “one, two, three, boom, boom.”

Meaning it works if you shut it off in time with the music?

I think that’s the key. A lot of songs, the tempos aren’t that slow, so the pedal allows for that—even if you stomp on beat, it will stop for you. But if the bpm [beats per minute] is slow, the pedal won’t know.

And it will add another loop?

Yeah.

In past interviews, you’ve mentioned another frustration working with loopers is that you’re limited to one key for the duration of a song. Have you worked around that?

The advantage of playing with two people is there can be two things going at once. With Takako, this allows a nicer transition from one idea to another. There’s a song on our new record called “Zaaab.” The first half, I believe, is in C-sharp and the second half is in B. So we do subtle key changes. But when it’s within a loop, it’s very difficult. You can artificially change the key using a pitch-shifting pedal, but you would hear artifacts. I know some friends who use that trick and it’s really cool, but the quality of the music changes. It gets this bit-crushed sound.

In your signal chain, you surround the looper with two Boss DD-3s—one on either side. Why is that?

This lets me time the music to the delay settings. For example, if I have the delay after the looper while I’m starting the song, the guitar is effected and blaring. At a certain point, when I’m going to introduce another element to make a dramatic musical change, I can cut the delay pedal and you hear all the layers run without the delay. Also, different parts of the delay pedals correspond to each other.

How so?

The delay time knob at the 7 o’clock and the 12 o’clock positions correspond—7 o’clock, 12 o’clock, and 5 o’clock all work together.

Meaning one is a double or quadruple of the other?

Yes. In the middle of the song, I can change the delay settings, turn the delay on after the loop, and it will change the rhythm of the music. Sometimes it will be a shuffle or everything’s offbeat or double time.

So if you put it at 9 o’clock you get a jerky feel?

Yeah. But it’s more like 10 o’clock. I can use them together. Adding more feedback on the delay pedal can change how the textures correspond to each other.

Dustin Wong’s Gear

Guitars

• Mid-’80s Japanese Fender Telecaster

Effects

• Boss TU-3 tuner

• Foxrox Octron octave pedal

• Analog Man Distortion (modded Boss DS-1)

• ISP Decimator noise gate

• 2 Boss DD-3 digital delays

• DigiTech Synth Wah

• Boss Harmonist PS-6

• TC Electronic Ditto Looper X2

Strings and Picks

• D’Addario EXL110 (.010–.046)

• Dunlop .73 mm nylon picks

You also have a noise gate. Do you use it as an effect or just to keep out hiss?

To keep out hiss. Especially in the beginning when I was using amps, I’d have the distortion on and the background noise would build up and the song would get dirty. The noise gate also cuts the normal, subtle hiss of the actual guitar, too. It keeps the loop clean. The noise gate is after everything that changes the guitar’s sound and the delay comes after.

What’s the mod you have on your Boss DS-1 distortion?

It’s the Analog Man Distortion mod. I believe they put in a better chip. On a normal DS-1, with the high-gain distortion, it feels very compressed—like the wave forms are squashed—but with this mod it sounds more dynamic, more textured.

But basically, you like to keep it simple.

Yup. [Laughs.] For a long time, I had just one power source for all the pedals. Recently, I bought another power source. I’m much happier.

What do you use?

I had a Truetone 1 Spot for everything, with a daisy chain. I’m now using two for all my pedals, it just cuts off so much noise. When there’s not enough power going through the pedals you get so much more noise.

Have you tried using batteries? Isn’t that the most silent way to operate them?

That’s what I hear, but it’s expensive! [Laughs.] It would get really heavy, too.

Let’s talk about your picking technique. You play both with a pick and your fingers. Is your fingerstyle technique traditional or more of a hybrid?

I use three fingers. I listened to a lot of John Fahey when I was in college and I admired his style, but I couldn’t mimic that type of folk-guitar picking. So I decided I shouldn’t mimic his folk fingerpicking style, I should just practice on my own—come up with my own style. It was more a way to get percussive—to make the guitar not sound like a guitar. I palm mute it and mainly use my fingertips rather than my nails. That gets more of a hand-drum sound.

Have you experimented with different tunings?

I did in the beginning because I didn’t understand the geography of the guitar. I’m self-taught and it was all shapes to me. It was small square to bigger square to rectangle—that kind of idea. But once I got the loop pedal, I started to figure it out—the loop pedal was my teacher. Writing all those songs on the loop pedal was a real learning experience musically, really fundamental. I had dexterity somewhat, but I didn’t know what I was doing. Especially with Ponytail, it was like, “What key are we in? I have no idea.” It took so long to write songs because we knew how to play, but we didn’t know what we were playing.

And the loop pedal taught you how to find what works against what?

Exactly. In the beginning, it was mostly pentatonic because that was so easy for me. That was the first thing the band was doing. Then I was like, “There are these minor notes. There are scales.” Now I feel confident about all those things.

Have you studied more advanced theory since you’ve been playing? Have you learned about dissonance and harmony?

Through osmosis I’ve been getting more into the ideas of jazz, playing the notes that are in between the keys, and that’s been super fun.

Do you practice your pedals as instruments as well?

For sure. I think pedals are definitely instruments.

What is your process? Do you work through different settings on each knob?

Yes, and then in combination with other pedals. I’ll do different settings with two pedals and see how they sound. Trial and error. I start to figure out what sounds I like from the pedals and where to set them depending on what works.

Do you take notes?

It’s better when it’s second nature.

Why don’t you use an amp?

My house got broken into at one point when I was on tour. When I got back, my amp was gone, my second guitar was gone, a lot of my equipment was taken—mics for recording—all this stuff. Amps can get pretty expensive. I had a tube amp, an ’80s Fender Twin called the “Evil Twin.” I think that’s the name. It was the one with the red knobs. I loved that amp. It had a great sound. [Editor’s note: There’s a raging debate in amp forums as to which Fender Twin is the actual “Evil Twin.” Some say the ’80s-era Twin earned the nickname because its red knobs gave it a sinister look. Others disagree for various reasons and claim it refers to a smaller-knobbed mid-’90s Twin.] I decided, “Well, I have a mixer. I can go directly into the mixer and practice with headphones.” And then I realized, “This is a completely new sound.” It was really refreshing to me.

Then I was playing my solo stuff on tour in the U.K. I was in a town called Hull. I played this club—the deal was that every venue would have an amp for me to use—and the guy there said, “The amps are back there. You can use any.” They were, but all the knobs were coming off the amps and the springs were out. I thought, “This is terrible. I’m not going to be able to play.” The owner said, “Why don’t you just go direct into the PA?” And at the time I thought, “That is so blasphemous. I can’t believe you said that to me.” But then I tried it and I realized you can control the low end more. It was cleaner. I thought, “I can actually get into this.” So I’ve been going DI for a while now. Of course, when I’m playing with other people—with a drummer and bassist—I’ll plug into an amp.

YouTube It

Listen to “Elastic Astral Peel” from Are Euphoria by Dusting Wong and Takako Minekawa and dig the trippy visuals that pulse, throb, and morph with the music.

Dustin Wong’s utilitarian Telecaster has been rewired with vintage copper wire from the 1920s. “It’s Rockefeller-era wire,” he says, “and it sounds beautiful.” Photo by Hiromi Shinada

Dustin Wong’s main axe—his only axe—is a modestly modded, mid-1980s, Japanese-made Fender Telecaster. A few of his modifications are simple and were done to make playing easier—like flipping the control plate so the volume knob sits where the pickup selector usually does.

But others are more subtle.

“The pickup selector is modern American, but the electronics are connected with vintage copper wire,” Wong says. “The capacitor is an old 1940s unit called the Bumblebee. It warms things up. When it’s clean, it’s clean.” Using older electronics was his tech’s suggestion. “He had this copper wire from 1920s America, like Rockefeller-era wire,” Wong explains. “He had all this stuff that was almost a century old. He put it in and it sounds beautiful.” Wong’s technician is particular about wire but not the pickups themselves. “I’m sure every guitar technician has a different theory,” Wong adds. “But his theory is that it’s not about the pickups, it’s about the wires and solder. He says to put on as little solder as possible. When he puts the solder on, it’s like he’s painting with a tiny paintbrush.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)