Twenty-eight years after his death, Jerry Garcia may be more famous than ever. There are reputed to be over 5,000 Grateful Dead cover bands in the U.S. alone. Guitarists in towns small and large mine his electric guitar solos for existential wisdom, and his bright, chiming tone and laid-back lyricism continues to enthrall successive generations. What is less talked about is his acoustic guitar playing, which is, after all, where it all began.

One cannot fully understand the man without knowing how powerful and enduring the acoustic guitar remained in his life. Picture the West Coast in 1962; this is before everything went electric. What’s in the air is the Folk Revival. A generation of young urban kids had discovered American folk music, old-time, bluegrass, ragtime, and Delta blues, whether it was Woody Guthrie, Clarence Ashley, Bill Monroe, or Reverend Gary Davis. Plenty of future rock ’n’ rollers, including Jorma Kaukonen, John Sebastian, and Mike Bloomfield, absorbed this music, but none climbed as deep into its corners as Garcia.

Our recorded evidence goes as far back as 1961, when Jerry played banjo and guitar with the Black Mountain Boys, the Hart Valley Drifters, and other Bay Area outfits that included contemporaries like Eric Thompson on guitar, future Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter on bass, and multi-instrumentalist Sandy Rothman. What strikes the listener is how burning these early recordings are. Jerry, barely out of his teens, mostly on banjo, has gone straight into the hardcore stuff. This music, coming from the likes of the Stanley Brothers, Bill Monroe, and the Osborne Brothers, is not for the faint of heart. It’s virtuosic, wild, and, in its purest form, downright scary. Death and violence run amok in many of their lyrics. As Jerry’s longtime ally, mandolinist David Grisman, put it, “Back then, all of it was pretty hardcore compared to the ‘pop grass’ of today.”

Jerry followed Bill Monroe around for close to a year and is reputed to have approached the father of bluegrass to audition for his band. He studied numerous lesser-known figures, too: Dock Boggs, flat-picker Tom Paley from the New Lost City Ramblers, Mississippi John Hurt. In the mid-’60s, he set aside the banjo to focus on guitar, because as he put it, “I’d worn the banjo out.”

“In the mid-’60s, he set aside the banjo to focus on guitar, because as he put it, ‘I’d worn the banjo out.’”

Garcia’s voracious appetite for American musical history drove him to dive into a subject and completely exhaust it, absorbing new influences like proteins. A set in those days might include bluegrass staples like “Rosa Lee McFall” and “John Hardy,” but also folk tunes that Peter, Paul and Mary or Joan Baez might cover: “All My Trials,” “Rake and Rambling Boy,” “Gilgarra Mountain.” There were also classics from the old-time repertoire, such as “Shady Grove” (a Doc Watson favorite) and “Man of Constant Sorrow,” along with Mississippi John Hurt’s “Louis Collins” or Lead Belly’s “Good Night Irene.”

The locus for this outpouring of West Coast roots-music activity was the South Bay, Palo Alto, and Menlo Park—community gathering spots where the culture turned from beatnik to hippie. The precursor of the Grateful Dead was the Palo Alto-based, all-acoustic Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions. Jug bands had roots in early African American history, but at that time the main influence among the young, white players in the genre was the Jim Kweskin Jug Band.

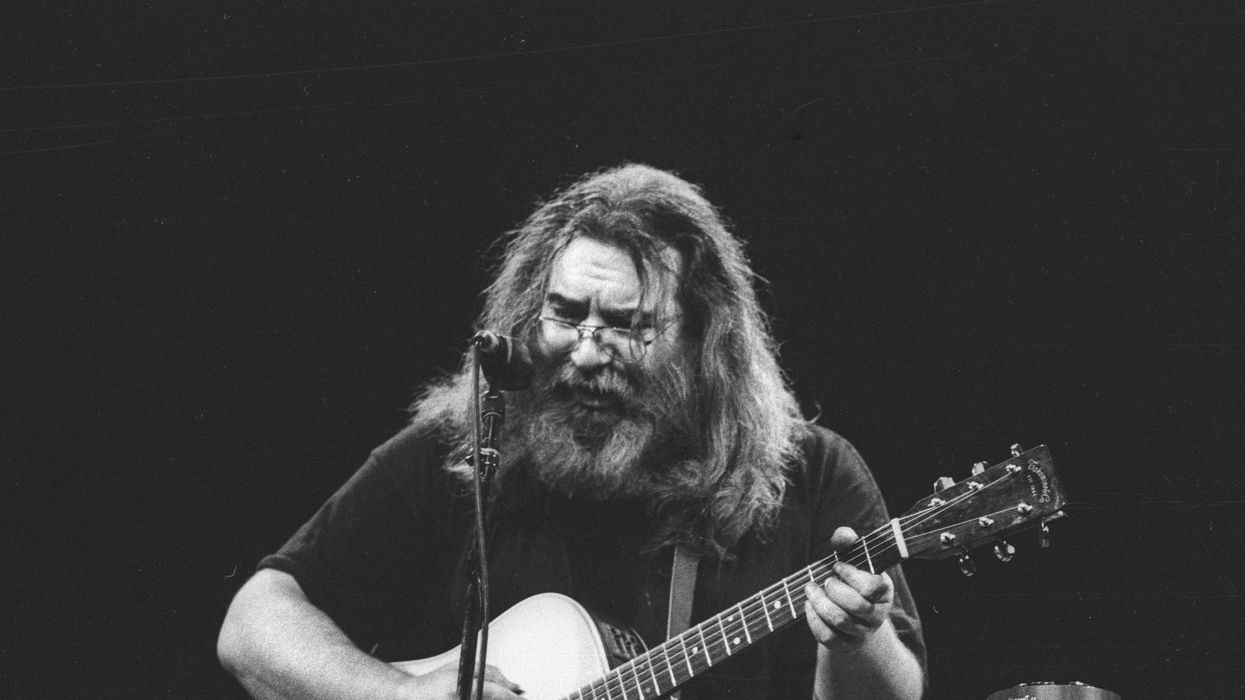

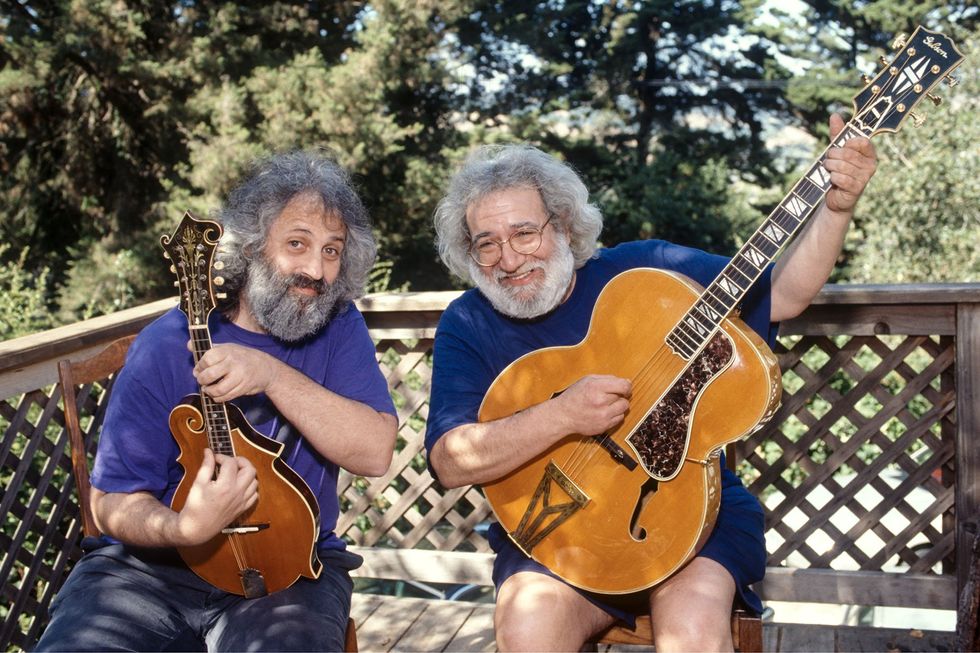

Hot dawgs: Garcia and his acoustic-mandolin-playing cohort, David Grisman, clearly enjoyed hanging out together on the 1993 day in Mill Valley, California, when this shot was taken.

Photo by Susana Millman

When most musicians play traditional American tunes, especially bluegrass, they hew to a set of timeworn principles and licks from which they extrapolate. Jerry didn’t do that so much, though he knew plenty of those licks. He made the music his own. He accompanied himself as a singer on acoustic guitar as much as he did on electric, with a simple, strong picking hand. In solos, he ranged freely around the neck, not content to stay close to first position, like bluegrassers Jimmy Martin or Carter Stanley might. You never feel that he’s relying on much besides his ear. We hear the ever-present pull-offs, the chromatic approach tones, the hints at Tin Pan Alley harmony, and even the note-bending—all the stuff you find in his electric work.

“Calling himself ‘lazy,’ he suggested that playing acoustic could be a battle, and that this guitar generally made life easier.”

Consider “The Other One,” which often became a springboard for the Grateful Dead’s long electric jams. In more fiery renditions of this staple, Jerry plays long lines of eighth notes—a relentless stream that builds the energy much like a bluegrass solo, where the right hand never stops and rarely slows. In “Deal,” you hear the pre-war Tin Pan Alley sound, with echoes of early jazz. In “Cold Rain and Snow,” “Wharf Rat,” and “Loser,” you hear the modal drones of early country gospel, and the way Garcia solos evoke the primeval fiddle lines and moaning vocals of the nascent 20th century, back when death, murder, destitution, and lost love made up a lot of the lyrical subject matter. It’s a perfect mating. His flatpicking is at the heart of “Me and My Uncle,” “Cumberland Blues,” and “Brown-Eyed Women.” You hear some of early Merle Haggard and the Bakersfield sound, too.

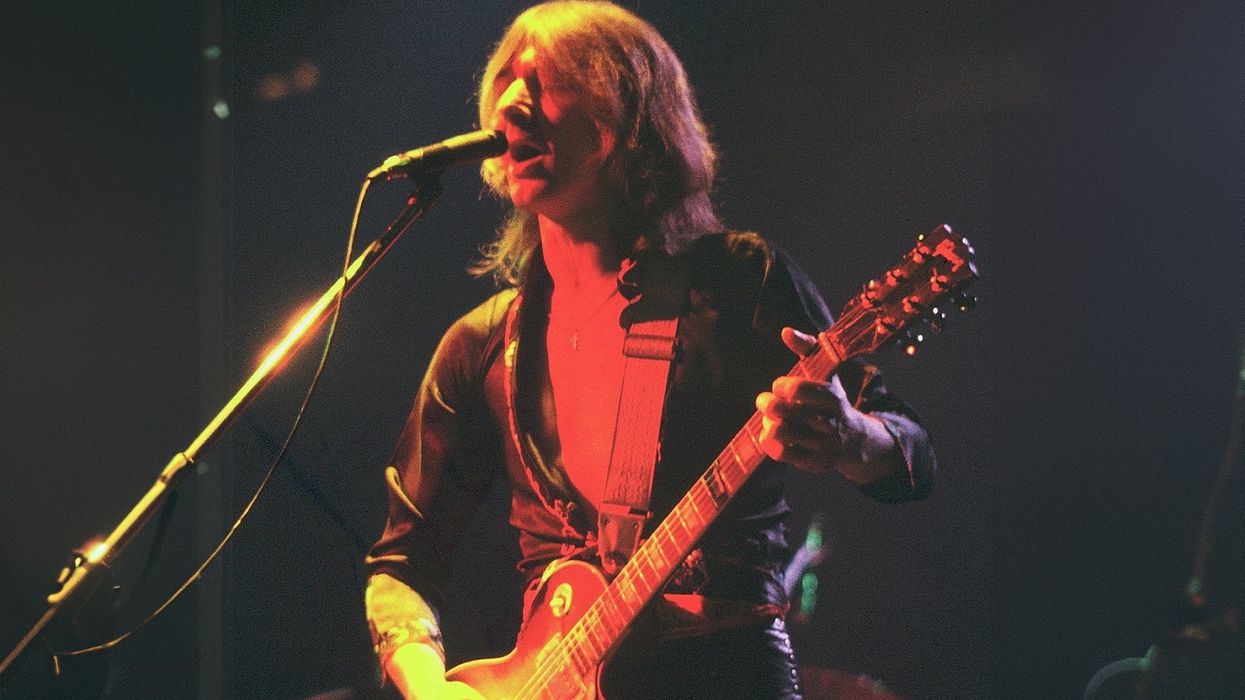

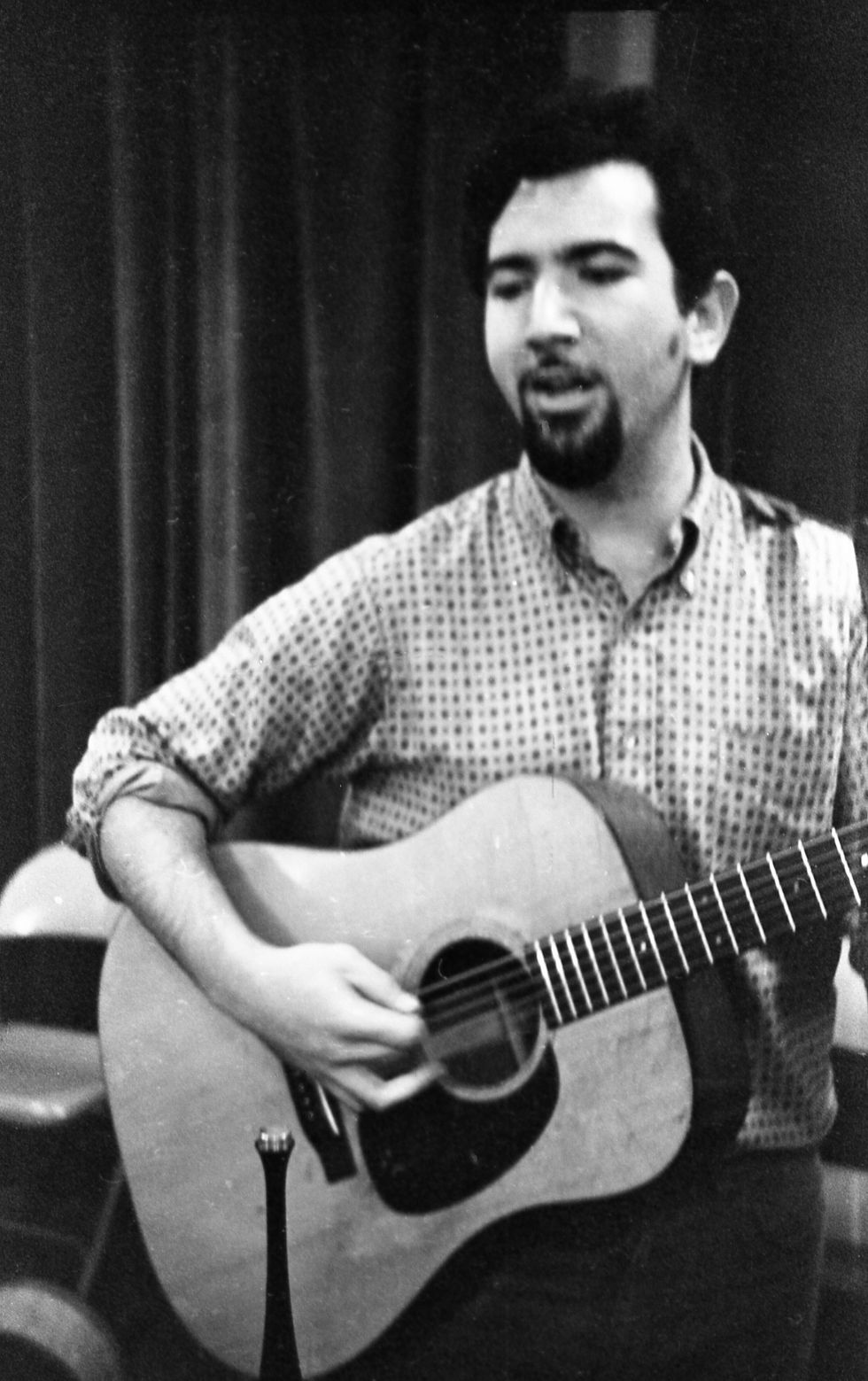

In the mid-’60s, Garcia set aside the banjo to focus on guitar, because as he put it, “I’d worn the banjo out.”

Photo by Jerald Melrose

And what of the gear that Jerry used through four decades of creating his signature approach to acoustic American roots music (which includes rock ’n’ roll)? Let’s start in 1980, when the Grateful Dead did an acoustic and electric tour of 25 shows with three sets per gig—the first set unplugged.

Jerry had grown tired of dealing with the sound of a miked acoustic. It was too unpredictable, too woofy. The sound of the guitar, he said, comes at you from a number of directions. To simply put a mic near the soundhole captures only a portion of the sound waves. When the first guitars with built-in pickups were made, and could be plugged straight into the soundboard, he went for it, bought a Takamine EF360S, and never looked back. Compared to, say, a Martin, these guitars are rather snappy in tone, emphasizing highs and mid highs. Jerry sometimes opted to further emphasize the brightness by picking close to the bridge. He told interviewer Jas Obrecht that he also favored the Takamine for how easy it played, compared to some of his earlier dreadnoughts. Calling himself “lazy,” he suggested that playing acoustic could be a battle, and that this guitar generally made life easier.

Way back in the early ’60s, Garcia played a big-bodied Guild F-50, and then a Martin D-21. As the decade progressed, he chose an Epiphone Texan, and a Martin 000-18S and 00-45. During the rail-riding 1970 Festival Express tour—captured in the excellent 2003-released film Festival Express—he was spotted playing a Martin D-18 and a D-28, and in 1978 he was using a Guild D-25. Jerry reportedly revisited his Martins in later years, but most often he performed and recorded with the Takamine or an Alvarez Yairi GY-1, aka the Jerry Garcia Model. The GY-1 was designed with Garcia’s input by Kazuo Yairi in the early ’90s. It boasts solid rosewood back and sides, an ebony fretboard, gold tuners, custom fretboard and headstock inlays, and Alvarez System 500 electronics. Today, vintage GY-1s sell for between $850 and $1,500, depending on their condition.

“He had the three T’s: tone, time and taste. And, most importantly, he had his own unique voice, immediately recognizable and distinctive.”—David Grisman

Jerry’s acoustic playing is at the heart of early Dead albums, such as Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty. When you hear “Ripple,” “Friend of the Devil,” “Dire Wolf,” “Uncle John’s Band,” and later, “Standing on the Moon” or “Mississippi Half-Step Uptown Toodeloo,” you’re hearing an incredible evolution of American song, in part thanks to his stellar fretwork.

The Alvarez Yairi GY-1 became known as the Jerry Garcia Model. It was designed with Garcia’s input by Kazuo Yairi in the early ’90s. It boasts a solid rosewood back and sides, an ebony fretboard, gold tuners, custom fretboard and headstock inlays, and Alvarez System 500 electronics.

Photo courtesy of Dark Matter Music Company/Reverb.com

I was at a couple of the Grateful Dead’s shows at San Francisco’s Warfield in 1980, during their acoustic and electric tour, and the experience was a revelation. It showed how strong the songs were, without the hue and cry of electricity. Sure, the Dead were a dance band, and a decidedly psychedelic band, but their acoustic playing revealed depths of intimacy that were a lovely counterpoint to all that. Some of Jerry’s most mournful material, Garcia’s “To Lay Me Down” and American Beauty’s “Brokedown Palace,” is even more heartbreaking when he’s in this setting. You feel the band’s subtle chemistry in a new way.

But as an acoustic player, Jerry is most clearly represented in his side projects, such as Old & In the Way, a first-class bluegrass outfit (with Jerry back on banjo) that stretched past traditional repertoire into songs by the Rolling Stones as well as mandolinist Dave Grisman’s and guitarist Peter Rowan’s “newgrass” originals. The Jerry Garcia Acoustic Band of the late ’80s harkened back to the Black Mountain Boys. The fiddle player in the band, Kenny Kosek, says the group started when some of Jerry’s old friends gathered by his hospital bed when he was recovering from his diabetic coma in 1987. They encouraged him to use the band as an opportunity to heal and renew.

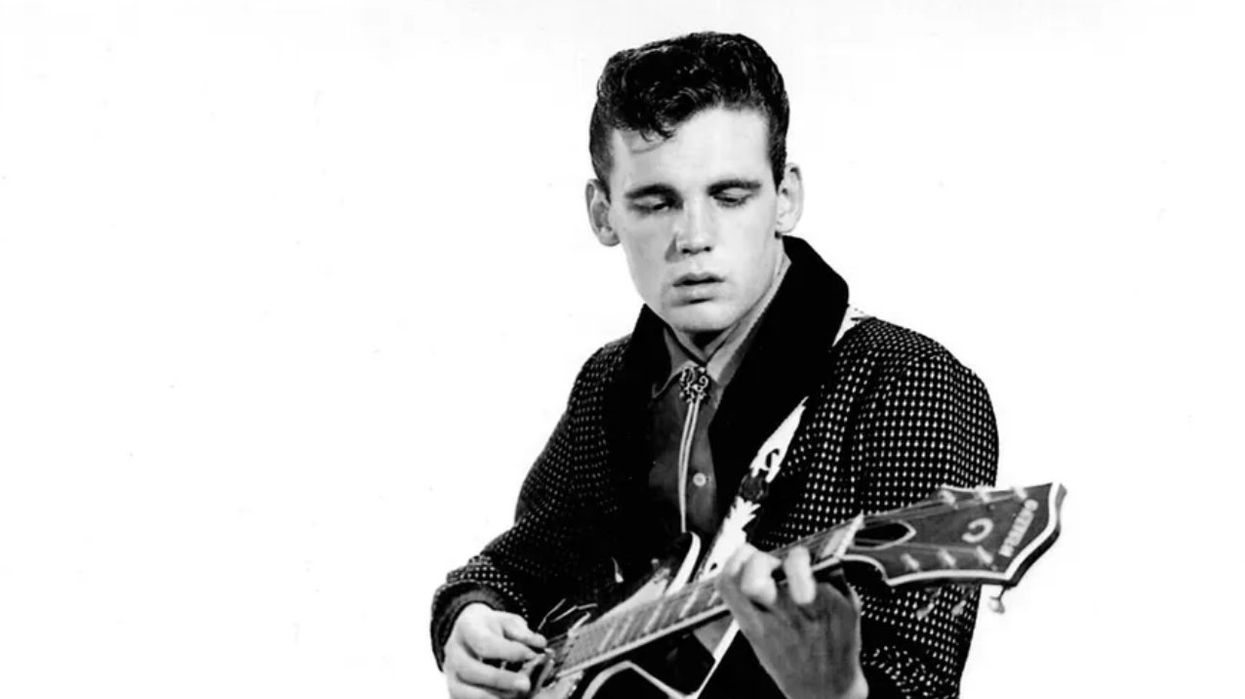

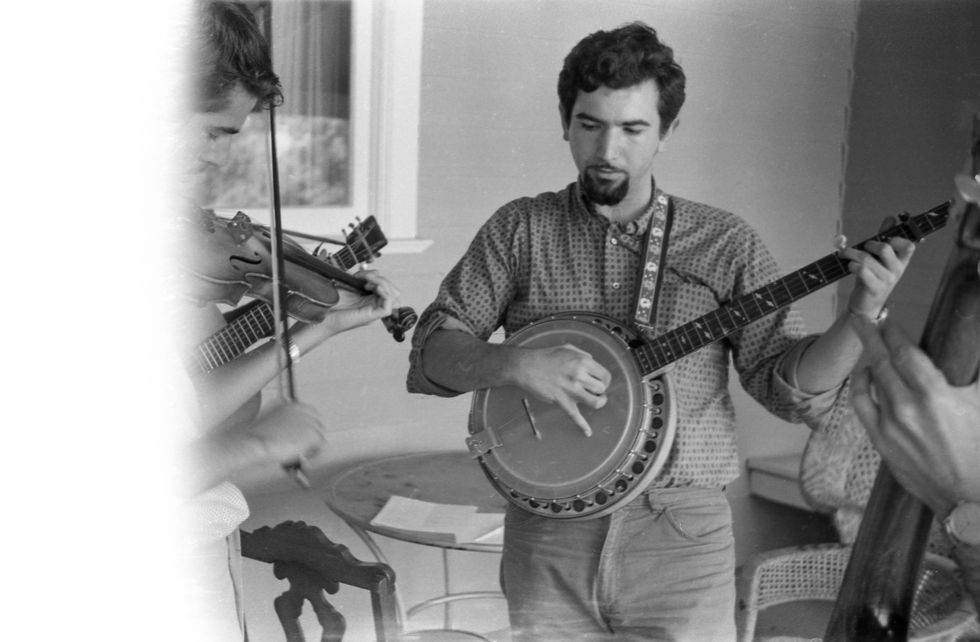

During his early years in bluegrass and old timey music, Garcia’s first recording instrument was the banjo, which he played in groups like the Black Mountain Boys.

Photo by Jerald Melrose

A charming piece of history is also found in the album The Pizza Tapes, an informal 1993 jam—released seven years later—with Grisman and bluegrass-guitar icon Tony Rice that was recorded in Grisman’s home and released after a bootleg began to circulate. It’s useful to contrast Garcia’s solos with Rice’s. Save for Doc Watson, Rice was possibly the greatest bluegrass guitarist to walk the planet, with enough technique to steamroll you right off the stage. But Jerry doesn’t flinch. He just wanders up and down the neck being Jerry—a little behind the beat, playing melodies … always melodies. He’s not out to compete with Rice, and, indeed, his collaborative approach was one of the Grateful Dead’s pillars. But it’s clear Garcia is no visitor to these stylistic realms as they play songs by John Hurt, Lefty Frizzell, Dylan, and even the Gershwins. He lives there.

The final act of Jerry as an acoustic guitarist was captured on the four Garcia/Grisman recordings of the ’90s. Talking to Grisman, who coined the term “Dawg Music” to describe the mix of bluegrass, folk, and jazz which he and Garcia loved, one can infer that this trove of material, recorded over many sessions at his house, came about partly because the Dead had become such a monolith. Stardom had its burdens, and Jerry didn’t care much for the pressure of being an object of worship. This music was a refuge, and Grisman describes the undertaking as “providential.” It’s moving to hear Garcia reach back to his roots with accumulated wisdom and gravitas … before he leaves us. His playing is deeply relaxed, his voice authoritative, resonant. He is an emotional interpreter, getting right to the soul of the tunes. These lesser-known recordings are some of the true gems in Jerry’s protean career, and luckily there are deluxe editions with a lot of music at Grisman’s acousticdisc.com.

The musicians who played acoustic music with Garcia all note the wide reach of his repertoire. Kenny Kosek describes feeling fully supported by Jerry, who infused that support with a sense of openness and playfulness. Grisman adds, “He had the three T’s: tone, time and taste. And, most importantly, he had his own unique voice, immediately recognizable and distinctive, reflecting his heavy addiction to listening to great music of all types.”

Joel Harrison wishes to thank David Grisman, Eric Thompson, Steve Kimock, and Jack Devine for assistance with this article.

YouTube It

Hear the Grateful Dead tackle an acoustic rendition of the 1920s song “Deep Elem Blues,” alluding to Dallas’ historic African American neighborhood. Yes, Jerry solos!

Get Some Jerry in Your Ears

If you’re not already familiar with Jerry Garcia’s acoustic playing, here are a few recommended recordings:

- “Uncle John’s Band,” Workingman’s Dead, The Grateful Dead (1970)

- “Jack-A-Roe,” Reckoning, The Grateful Dead (1981)

- “Whiskey in the Jar,” Shady Grove, David Grisman and Jerry Garcia (1996)

- “Louis Collins,” The Pizza Tapes, Jerry Garcia, David Grisman, and Tony Rice (2000)

- Before the Dead, four-CD/five-LP compilation of Jerry Garcia’s pre-Dead bands (2018)