Before the British Invasion of early 1964, it was rare to find skilled rock guitarists

who were stars in their own right. There were a few—Duane Eddy, Chuck Berry,

and Carl Perkins led the pack, with Link Wray and Lonnie Mack close behind—

but as a general rule, singers were the stars and guitarists were sidemen.

In 1966 and ’67—when rock and roll came of age and became rock—the “guitarist

as hero” was born. Some say this began with Eric Clapton, who was suddenly

thrust into the spotlight with his incendiary work on John Mayall’s Blues

Breakers with Eric Clapton (aka “the Beano album”). This LP introduced the

world to overdriven Les Paul-through-Marshall tone and blew a lot of young

guitarists’ minds, including a very impressionable Eddie Van Halen, who reputedly

learned Clapton’s solos note-for-note.

It was a dynamic time for rock guitar, as players began emerging from the

lead singer’s shadow. After Clapton left the Yardbirds to join Mayall, Jeff Beck

stepped into the band and began recording some of the most imaginative,

futuristic, and exploratory guitar the world had yet heard. Eventually, his friend

Jimmy Page joined the Yardbirds and continued to push the guitar’s sonic

boundaries before moving on to launch Led Zeppelin.

And then there was Jimi Hendrix—perhaps the ultimate rock guitar god—as

well as Chicagoan Mike Bloomfield (who first made waves in the Paul Butterfield

Blues Band), Pete Townshend, Keith Richards, and Peter Green and Mick Taylor

(both of whom launched their careers in Mayall’s Bluesbreakers). Dave Davies

of the Kinks, Jorma Kaukonen of Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead’s Jerry

Garcia, and Mountain’s Leslie West were also among the first generation of ’60s

guitar heroes. Most of them are still with us and musically active today.

But there are other guitarists who, for whatever reason, never received the recognition

or glory they deserved. As we examine some of these unsung heroes,

remember this is by no means a complete list. It would take an entire issue of

PG to pay homage to all the pioneering players of this era.

Vinny Martell

As the lead guitarist in Vanilla Fudge, Vinny

Martell electrified rock fans in the summer

of 1967 with a dramatic, slowed-down version

of the Supremes’ “You Keep Me Hangin’

On”—a track many feel bridged the gap

between psychedelia and heavy metal.

Vinny Martell onstage in April 2010 with his ’82 Les Paul Black Beauty. Photo by Bob Cianci

Martell, who was born in the Bronx, New York, joined the US Navy as a young man, and after his stint there he went on to play in bands in Florida before returning to New York. There, he formed a band called the Pigeons with Hammond B-3 organist and singer Mark Stein, bassist Tim Bogert, and drummer Joey Brennan. When the hard-rocking Carmine Appice replaced Brennan on drums, Vanilla Fudge was born. The quartet recorded five albums that consisted mostly of highly rearranged cover material. Their daring mix of soul, rock, and classical music influenced such bands as Deep Purple, Yes, and Led Zeppelin.

Initially, Vanilla Fudge’s music was dominated by Stein’s B-3. It wasn’t until the band’s fourth album, 1969’s Near the Beginning, that Martell came into his own as a guitarist. His playing on Beginning was punctuated by slashing chord work and impassioned blues-based solos that included the occasional Middle Eastern twist. Stein, Bogert, and Appice were powerful players and singers, so at first Martell’s role was to provide a musical foundation for the group. His bandmates also relied on him for moral support. “I was the spiritual guy in the group that held it all together,” says Martell. “I was the calm one who kept things cool. I think we would have splintered any number of times without my influence.”

Over time, Martell stepped into the limelight and also contributed to the band’s sophisticated arrangements. During the Fudge’s ’60s heyday, Martell played Gibson guitars— ES-335s, SGs, a big archtop L-5, and several Les Pauls, including a TV yellow Junior. For amps, Martell gigged with Magnatone, Fender, Standel, Kustom, Traynor, and Sunn models before settling on Marshall stacks. The Fudge split up in 1970, but since the ’90s they’ve regrouped many times for short tours, occasionally with all the original members. Martell also works local gigs with his own band. He currently plays an ’82 Les Paul Black Beauty, a Floyd Rose-equipped Kramer with a custom flame paint job, and several ESP guitars through Mesa/Boogie amplification. “ESP has been great to me,” says Martell. “When I go out on tour, I only bring two guitars—a red ESP that looks like a Les Paul and my Kramer.”

Vanilla Fudge’s progressive vision is documented in a four-disc box set from Rhino Records called Box of Fudge.

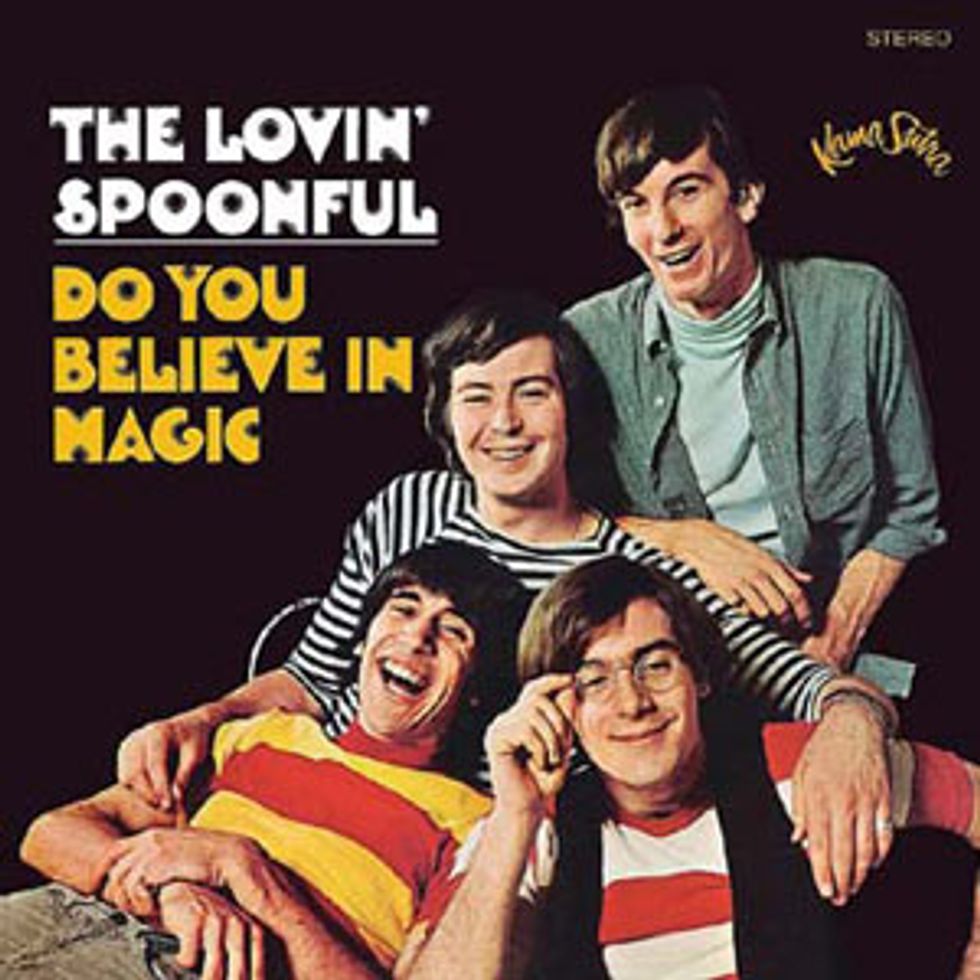

Zal Yanovsky

One of the great characters of ’60s rock,

Zal Yanovsky held the lead-guitar spot with

the Lovin’ Spoonful for most of the group’s

existence and played on all their hits, including

“Do You Believe in Magic,” “You Didn’t

Have to Be So Nice,” “Summer in the City,”

“Younger Girl,” and “Rain on the Roof.” An

ex-folkie, Canadian-born Yanovsky teamed

with Greenwich Village singer, songwriter,

and guitarist John Sebastian to form the

Spoonful in 1965.

One of the great characters of ’60s rock,

Zal Yanovsky held the lead-guitar spot with

the Lovin’ Spoonful for most of the group’s

existence and played on all their hits, including

“Do You Believe in Magic,” “You Didn’t

Have to Be So Nice,” “Summer in the City,”

“Younger Girl,” and “Rain on the Roof.” An

ex-folkie, Canadian-born Yanovsky teamed

with Greenwich Village singer, songwriter,

and guitarist John Sebastian to form the

Spoonful in 1965.The band’s good-time sound—a mixture of rock, blues, country, folk, and jug-band music—brought them immediate success and challenged the stranglehold that British groups had on the charts at the time. Yanovsky was an accomplished guitarist who could handle straight blues, raucous rock, sensitive chord work, country licks, and much more. He played for the song and delivered exactly what was necessary to make each one work. Yanovsky was also one of the very few guitarists who played the Gumby-shaped Guild S-200 Thunderbird solidbody. He had two—one with a sunburst finish and another with custom purple paint—which he played through Standel amplifiers.

After a drug bust in 1967, Yanovsky left the Spoonful and recorded his only solo album, the now collectible Alive and Well in Argentina, on which he sang and played most of the instruments. He returned home to Kingston, Ontario, where he opened a restaurant, Chez Piggy, followed by the Pan Chancho bakery. Both ventures were highly successful.

When the Lovin’ Spoonful were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000, it was the last time all four original members would be reunited. During the end-of-festivities jam, Yanovsky took a solo on his battered S-200 that proved he had lost none of his youthful fire and drew smiles from Eric Clapton, an admitted fan, who was sharing the stage.

Yanovsky died of congestive heart failure in 2002, but thanks to the superb music he left behind, his legacy lives on.

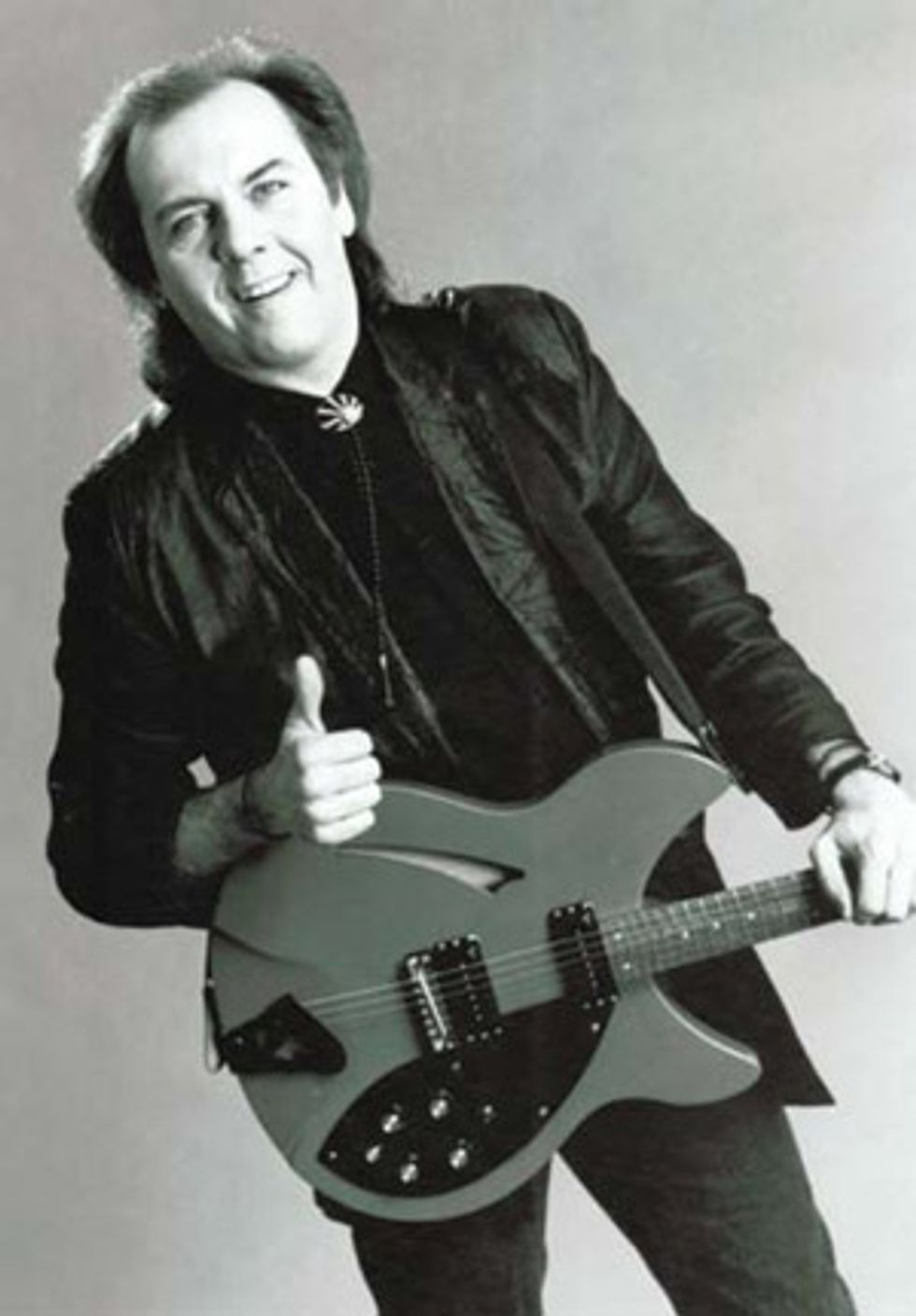

Gene Cornish

Gene Cornish achieved incredible success as guitarist for the Rascals. A Canadian by birth, Cornish was a seasoned music-business veteran by the time he joined the band in 1965, following a stint with Joey Dee & the Starliters, where he met future Rascals Felix Cavaliere and Eddie Brigati. With the addition of powerhouse drummer Dino Danelli, the Rascals scored numerous hits before disbanding in 1972.

Gene Cornish of the Rascals poses with his Rickenbacker semi-hollowbody in this 1989 publicity photo.

Never known as a flashy lead player, Cornish excelled at rhythm guitar and tried to move with the times as the music dictated. His use of fuzz on the single, “Come on Up,” was gnarly and effective, his chord work on “Groovin’” was tasty, and his funky licks on “In the Midnight Hour” would have made Steve Cropper proud. Cornish still works with drummer Danelli in the New Rascals, and all four original members performed a reunion show in early 2010.

In the ’60s, Cornish favored Gibson Barney Kessel archtops. Today, he plays Stratocaster-style guitars. In 1997, the Rascals were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

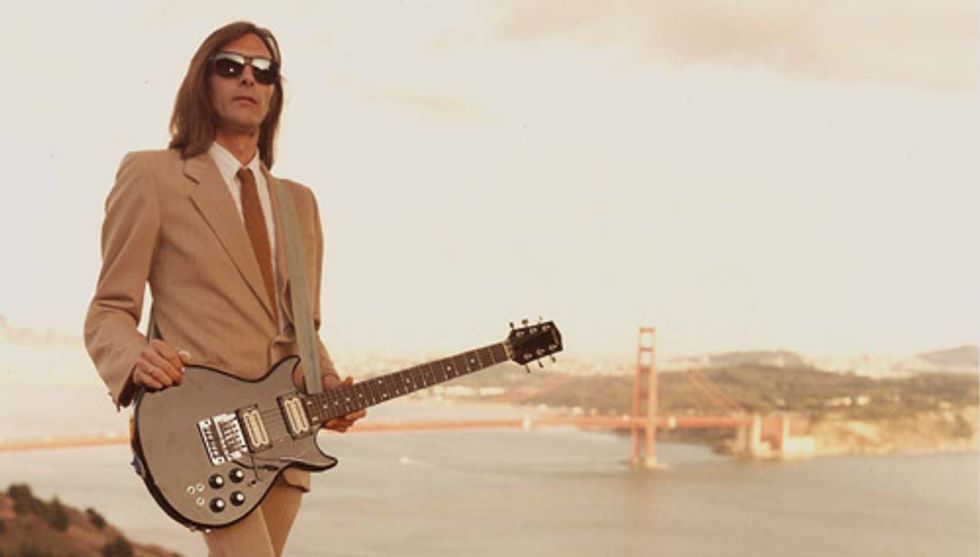

John Cipollina

John Cipollina of San Francisco’s Quicksilver Messenger Service was one of the most original and talented guitarists of the psychedelic era. Cipollina made extensive use of the Bigsby tremolo on his two highly customized “bat wing” Gibson SGs—a result, legend has it, of his inability to master finger vibrato.

John Cipollina with a Kahler-equipped Carvin double-cutaway just north of San Francisco circa 1987. Photo by Alan Blaustein

Using a thumbpick and fingerpicks, Cipollina achieved his trademark tones through an unusual rig consisting of solid-state Standel and Fender tube amps, coupled with large Wurlitzer horns, echo units, and effects pedals. His background in classical guitar and piano gave him a different perspective than other rock guitarists of the era who relied heavily on the pentatonic blues scale for their solos and riffs.

Cipollina continued to work in various San Francisco-area bands until his death in 1989 due to chronic emphysema. His family donated his favorite SG, along with his amp and effects rig, to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, where it is on prominent display in the museum.

Quicksilver’s other guitarist, Gary Duncan, also bears mention. His early work in the garage band the Brogues paid homage to Yardbirds-era Jeff Beck, but in Quicksilver he expanded his palette to include jazz licks and sitar-like phrasing that blended effectively with Cipollina’s quivering sounds. With their divergent approaches, Duncan and Cipollina managed to stay out of each other’s way and form an extremely simpatico dual-guitar team. Duncan still lives in the Bay area and occasionally tours with an updated version of Quicksilver Messenger Service. In the late ’60s, he played a Gibson L-5, an ES-335, and a ’56 Les Paul Custom, but he eventually shifted to Fender Stratocasters and Norlin-era Gibson Firebirds and Les Pauls.

Michael Monarch

When 17-year-old Michael Monarch joined Steppenwolf in 1967, he’d only been playing guitar for a few years. Nonetheless, he helped the band score their first big hit with the biker anthem, “Born to Be Wild.” Armed with a candy- apple-red Fender Esquire blowing through a fuzz box and Fender Concert or Bandmaster amps, he tracked three albums with Steppenwolf before getting his walking papers in 1969, just before the release of At Your Birthday Party.

Michael Monarch with his customized Fender Strat. Photo by DJ Moore

In the ’70s, Monarch put together a moderately successful band called Detective with singer Michael Des Barres, and he has worked for years with a group called World Classic Rockers, which includes Denny Laine of the Moody Blues, Spencer Davis, Randy Meisner of Poco and the Eagles, and other music-biz veterans.

Monarch, who now favors Stratocasters, has also released several diverse solo instrumental albums, and he’s done extensive scoring work for television and movies.

Randy California

Randy “California” Wolfe will forever be remembered

as the guitarist with the progressive band

Spirit, which scored medium-sized hits with “I

Got a Line on You” and “Nature’s Way” in the

late ’60s. The group’s eclectic sound incorporated

rock, blues, jazz, folk, and Latin influences.

Sparked by California’s thoughtful, forward-thinking

guitar work, Spirit was known for their

lively gigs. California was given his moniker by

none other than Jimi Hendrix, who he played

with in 1966 in New York City.

Randy “California” Wolfe will forever be remembered

as the guitarist with the progressive band

Spirit, which scored medium-sized hits with “I

Got a Line on You” and “Nature’s Way” in the

late ’60s. The group’s eclectic sound incorporated

rock, blues, jazz, folk, and Latin influences.

Sparked by California’s thoughtful, forward-thinking

guitar work, Spirit was known for their

lively gigs. California was given his moniker by

none other than Jimi Hendrix, who he played

with in 1966 in New York City.Spirit split up in 1971, while still riding the success of their album Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus. Later, California gigged and recorded with his stepfather, Spirit drummer Ed Cassidy, along with numerous bass players. He also released several solo records that were snatched up by a rabid cult following.

California played inexpensive Silvertone-branded Danelectro guitars in the early days of Spirit, but he later switched to Stratocasters, the occasional Les Paul, and finally Charvel guitars.

In January 1997, California and his son Quinn were swimming in the ocean off the coast of Molokai, Hawaii, when they were caught in a riptide. California managed to push Quinn to safety, but he drowned in the process and his body was never recovered.

Dick Wagner

Few guitarists have sustained as rewarding a career as Detroit native Dick Wagner, lead guitarist with the Frost, a hard-rock band that recorded three LPs for Vanguard Records. Wagner is probably best known as Alice Cooper’s collaborator, writing partner, and bandleader, but most guitarists will remember him as one half of the incredible guitar team on Lou Reed’s live Rock n Roll Animal LP. Wagner’s six-string partner was Steve Hunter, and their playing on that record is a guitar junkie’s dream come true. If you’ve never heard their twinguitar work, be sure to check it out.

Photo from the collection of Dick Wagner

Wagner co-wrote more than 50 songs and recorded some 19 albums with Cooper, and their association yielded numerous hits. Wagner has earned a stack of platinum and gold album awards, and he has songwriter or guitarist credits on more than 150 albums. In the ’90s, Wagner started a record label and talent agency. He continues to play—usually a sunburst 1959 Les Paul reissue—and he’s still a prolific songwriter.

Erik Braunn

Erik Braunn (sometimes known as Erik Brann)

was only 16 when he joined Iron Butterfly

just in time to record the band’s second

album, In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida. The album sold an astounding

20 million copies

and earned the

band repeated

platinum awards.

Braunn’s nowlegendary

guitar

riff that powered

the album’s title

song inspired

thousands of

young guitarists,

and perhaps

generated almost

as many derisive

comments. His extended solo on the tune practically defined the

term “psychedelic guitar” at the time.

Erik Braunn (sometimes known as Erik Brann)

was only 16 when he joined Iron Butterfly

just in time to record the band’s second

album, In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida. The album sold an astounding

20 million copies

and earned the

band repeated

platinum awards.

Braunn’s nowlegendary

guitar

riff that powered

the album’s title

song inspired

thousands of

young guitarists,

and perhaps

generated almost

as many derisive

comments. His extended solo on the tune practically defined the

term “psychedelic guitar” at the time.Braunn was always closely associated with Mosrite Ventures model guitars, and he favored Vox Super Beatle amps for live work. At the end of his life, he endorsed Taylor acoustics. He suffered cardiac arrest and died in July 2003.

Jerry Miller

Although Moby

Grape hailed from

San Francisco,

their lead guitarist,

Jerry Miller, was a

native of Tacoma,

Washington. He

worked the local

blues and rock

circuit and played

with Bobby Fuller

before the late

songwriter scored

a national hit with

“I Fought the Law.”

Miller formed Moby Grape in ’67 with fellow guitarists Skip Spence

and Peter Lewis, bassist Bob Mosley, and drummer Don Stevenson.

The band’s debut album, 1967’s Moby Grape, was hailed by many

fans and critics as the best guitar record to come out of San Francisco

during that heady era. But the Grape quickly fell apart as a result of

bad business decisions, managerial problems, record-company blunders,

drug busts, ego clashes, and even chemically induced madness.

Although Moby

Grape hailed from

San Francisco,

their lead guitarist,

Jerry Miller, was a

native of Tacoma,

Washington. He

worked the local

blues and rock

circuit and played

with Bobby Fuller

before the late

songwriter scored

a national hit with

“I Fought the Law.”

Miller formed Moby Grape in ’67 with fellow guitarists Skip Spence

and Peter Lewis, bassist Bob Mosley, and drummer Don Stevenson.

The band’s debut album, 1967’s Moby Grape, was hailed by many

fans and critics as the best guitar record to come out of San Francisco

during that heady era. But the Grape quickly fell apart as a result of

bad business decisions, managerial problems, record-company blunders,

drug busts, ego clashes, and even chemically induced madness.Through all the craziness, Miller’s lead guitar shone like a beacon in the night. A funky blues player, he nonetheless had an affinity for rock, country, and folk—and it shows in the band’s diverse music. There have been numerous Moby Grape reunions and sessions over the years, and Miller has been present for all of them. At age 67, he continues to work in the Tacoma area with his own band, and he still plays vintage Gibson L-5 archtops.

Eddie Phillips

Jimmy Page did not invent the violin-bow guitar technique.

It was London-born Eddie Phillips—a progressive, criminally underrated guitarist—who used the bow

extensively on his cherry red Gibson ES-335.

With his band the Creation, Phillips produced

some of the coolest British freakbeat

(a British musical style that paralleled

American psychedelic music circa 1967) and

art-rock records of the day. Aggressive yet

catchy, the Creation’s music appealed to the

Who’s mod fans. The band is remembered

for “Making Time,” “Painter Man,” and

“Biff Bang Pow,” among other songs.

Phillips, who was quoted as saying “Our

music is red—with purple flashes,” was also

a pioneer of feedback and distortion, and

his playing coincidentally mirrored that of

Pete Townshend.

Jimmy Page did not invent the violin-bow guitar technique.

It was London-born Eddie Phillips—a progressive, criminally underrated guitarist—who used the bow

extensively on his cherry red Gibson ES-335.

With his band the Creation, Phillips produced

some of the coolest British freakbeat

(a British musical style that paralleled

American psychedelic music circa 1967) and

art-rock records of the day. Aggressive yet

catchy, the Creation’s music appealed to the

Who’s mod fans. The band is remembered

for “Making Time,” “Painter Man,” and

“Biff Bang Pow,” among other songs.

Phillips, who was quoted as saying “Our

music is red—with purple flashes,” was also

a pioneer of feedback and distortion, and

his playing coincidentally mirrored that of

Pete Townshend.Although they became stars in Germany, the Creation only scored two minor hits in England and never cracked the US charts. The band splintered after a short time, and Phillips eventually left the music business to take a job driving a bus. However, he couldn’t entirely resist music’s allure, and over the years, Phillips reformed the Creation for live gigs and recording sessions. The band is still at it today, though Phillips is the only original member.

Roy Wood

Finally, Roy Wood—lead guitarist with the

Move and co-founder of Electric Light

Orchestra—should be recognized for his

guitar skills. Known more as a songwriter

and ensemble player, Wood nonetheless

was an adept guitarist with an R&B and

roots-rock background. Playing a white

pre-CBS Fender Strat and a Fender Electric

XII on such Move cuts as “Fire Brigade,”

“Flowers in the Rain,” “Night of Fear,” “I

Can Hear the Grass Grow,” “Brontosaurus,”

and “Kilroy Was Here,” Wood epitomized

the jangly British power pop of the mid

to late ’60s.

Finally, Roy Wood—lead guitarist with the

Move and co-founder of Electric Light

Orchestra—should be recognized for his

guitar skills. Known more as a songwriter

and ensemble player, Wood nonetheless

was an adept guitarist with an R&B and

roots-rock background. Playing a white

pre-CBS Fender Strat and a Fender Electric

XII on such Move cuts as “Fire Brigade,”

“Flowers in the Rain,” “Night of Fear,” “I

Can Hear the Grass Grow,” “Brontosaurus,”

and “Kilroy Was Here,” Wood epitomized

the jangly British power pop of the mid

to late ’60s.The Move eventually morphed into Electric Light Orchestra with guitarist Jeff Lynne aboard, but Wood’s time with ELO was short—he left after their first album. Following his stint with ELO, Wood enjoyed chart success with his own band, Wizzard. Though Wood is now semi-retired, he ventures out occasionally for live gigs.

Honoring Rock’s Forebears

The obvious guitar gods were not the only ones making waves in ’60s rock music. The gods were often simply those guitarists who got the most press. All the lesser-known players in this story have one thing in common: They went about their business without much fanfare and contributed positively to the music, art, and culture of that tumultuous time. In doing so, they made their mark in their own special ways.

When you get a chance, dig into those dusty vinyl LPs in your basement or go through your dad’s record collection. You may discover a special guitarist who will inspire you to explore new musical directions.