When the Descendents came together in 1978, the Southern California quartet reveled in their youthfulness. The band spited their parents and glorified coffee and fast food in quick songs merging punk and thrash with pop hooks.

Almost 40 years later, the group sticks to their musical winning formula, one to which all modern pop-punks, from Green Day to Blink 182, are indebted. The lyrics, though, have shifted to reflect the band's age. All the current members—singer Milo Aukerman, guitarist Stephen Egerton, bassist Karl Alvarez, and drummer Bill Stevenson—are in their early 50s. On Hypercaffium Spazzinate, the Descendents' first album in 12 years, the group laments such concerns as the health consequences of a fast-food diet and the administration of ADHD medicine to their children.

Egerton, who has been with the Descendents since 1987, remains an energetic and limber musician in middle age. His rhythmically cohesive bursts of sound give the group's songs a consistent urgency, and his ear for nonstandard triadic chord progressions and catchy countermelodies adds an extra layer of musicality to the proceedings. And he's known to unleash a tastefully melodic guitar solo from time to time.

Egerton brings a similar approach to his work with All, an offshoot of the Descendents, and with FLAG, the current incarnation of the classic hardcore band Black Flag. His talents as a multi-instrumentalist are in full display on his 2010 solo debut, The Seven Degrees of Stephen Egerton, a collaboration with 16 different singers. Egerton also runs a recording studio at his Tulsa, Oklahoma, home base, where his day job involves engineering, mixing, and mastering music.

On a break from a studio session, Egerton phoned us to talk about some of his secret influences, how studying classical guitar made him a better punk musician, and the streamlined rigs he uses in the service of his deceptively simple style.

Let's start by talking about gear. What guitars and amps do you play?

I've been playing Music Man guitars now for coming up on 20 years. I think I got my first one in 1997. I call her Old Gray—she's a gray Axis and that's what I used on this last record. For amps I used a Blackstar HT 100. That's what I've been using for the last three or four years. It's been a good amp for me and I've been really happy with it.

Recently I got a new Music Man guitar called the StingRay. It's sort of a recreation of the guitar that Leo Fender launched Music Man with before Ernie Ball bought the company. I've had this guitar for two months now, and it's maybe my favorite guitar I've ever had. There's a little something special about it sonically. I wish I'd had it when we recorded the album, although maybe it would have only made a subtle difference.

I also play in FLAG—a bunch of members of Black Flag crossing over the many years that they were a band. In that band, in keeping with their original sonic ethos, I play a Dan Armstrong. It's a pretty modified guitar—not an old one but a reissue. I actually played an original Dan Armstrong for many years before I got my Music Man, but it got stolen and I didn't have one for many years. When FLAG plays—we sort of have intermittent bursts of playing—the newer Armstrong is the guitar I always use.

Factoid: The Descendents' guitarist Stephen Egerton and drummer Bill Stevenson produced the band's new album.

Your sound is pretty straightforward—do you use any effects at all?

I tend not to use effects or even knobs on my guitars. I use a lot of gain and tend to play louder in FLAG, so I do have a kill switch on the guitar. Lately I've been interested in getting into effects, and I do keep a few around. I do a little television music, like reality shows, all rock-based, and for some of the stuff where there are no words, I explore music that's a little different than what I'm normally associated with. I have a few oddball effects: a couple of reissue Ampeg pedals and a Danelectro spring reverb pedal that I really like. But again, with the Descendents and FLAG, I use no effects or even volume knobs.

How and why did you do away with knobs?

Years ago I just wired the pickup straight to the jack. It was really a practical matter, because I tend to play harder than I probably should and there was the issue of me slamming my hand into the volume knob or pickup selector switch when I played, and those electronics tended to rust out on me, so it was helpful to have them removed.

Why do you use the kill switch?

The Dan Armstrong has that kill switch because in FLAG there's more feedback happening and I use the switch to quiet things down here and there. If you listen to the old Black Flag records, the way they sometimes edited the songs is that they started with a blast of feedback, kind of spliced into the songs. I sometimes use the kill switch to recreate that effect.

Tell us a little about your musical history.

Music for me starts with the Beatles. When I was a kid they absolutely grabbed me. At age 5 I decided that's what I wanted to do, but I didn't start playing guitar till I was 9, when my mom showed me some basic open chords. The first music I learned to play was basic: Chuck Berry and '60s pop and rock, simple country music like John Prine. When I was a kid I used to play those songs for change in the shopping mall near my house. I wanted to be just like the Beatles, and that's how my career got started.

The first player that made me really think about the possibilities behind the guitar was Jeff Beck. A friend of my mother's who was a guitar player turned me on to Blow by Blow. That record sparked my interest in fusion music, and from there I went on to John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, which is still one of my very favorite things to listen to.

Somebody gave me a Frank Zappa record when I was 11, and that led to punk rock, which was really big around that time. Also, we had a lot of jazz records around my house when I was growing up, and I got into Wes Montgomery and players like that. I missed metal and went straight to fusion and jazz and punk.

How did you get into punk?

When I heard the first Sex Pistols record, which kind of blew my world apart. Punk was something that made sense to a person entering their teenage years. That kind of screw-you thing made good sense to me.

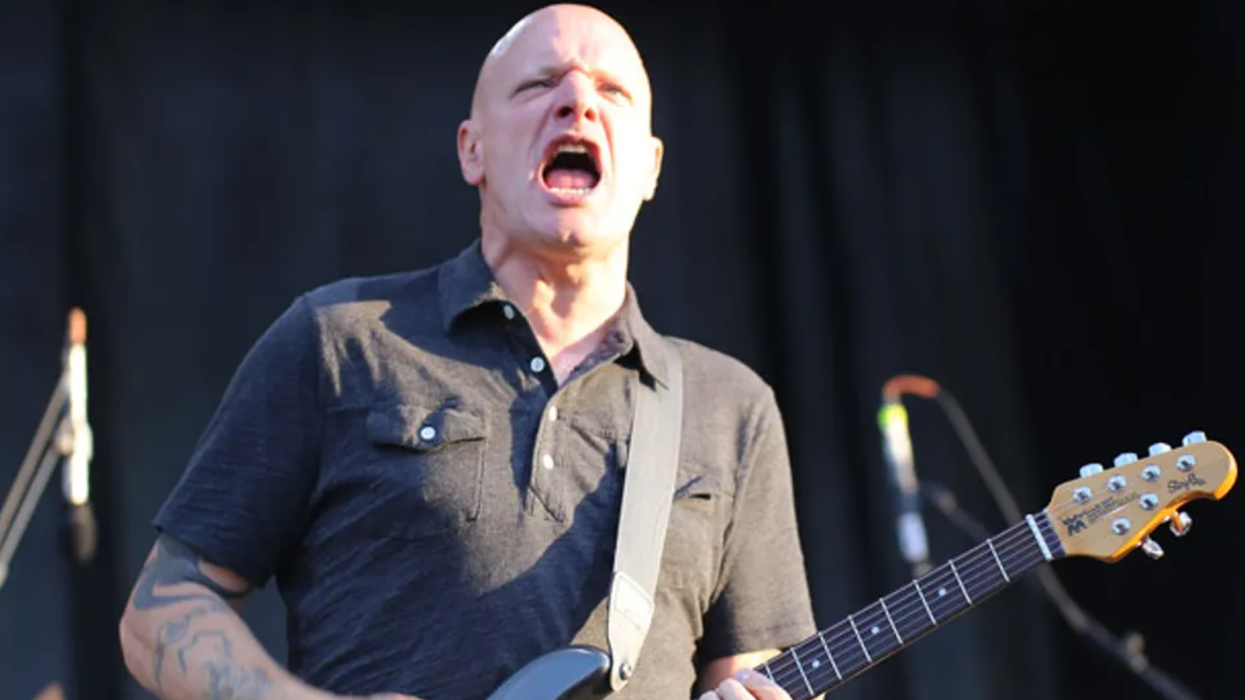

Punk rock and classic technique mix in Egerton's playing. He says studying classical guitar gave him “the ability to control all of the variables across the fretboard." Photo by Tim Bugbee: Tinnitus Photography

The influence of fusion guitarists isn't necessarily obvious in your work with the Descendents. Describe how Jeff Beck and other players have influenced you.

In the case of Jeff Beck, there's the guitar-hero guy who isn't really a shredder, but a lyrical guitarist—someone who can play a melody you can really glom onto as a listener. Same with John McLaughlin, although he can certainly go nuts, speed-wise. What's funny with the Mahavishnu Orchestra is that Bill Stevenson loves them, as does Karl Alvarez. We grew up together and listened to the same records. Greg Ginn in Black Flag is also super into the Mahavishnu Orchestra.

There's just something I hear in the music—ways of circumventing just playing typical blues guitar or being strictly a scale person. I don't approach the guitar that way. I tend to come up with triad chords I really like, then find a melody and try to come up with something interesting to add to it. Much of that harmonic and melodic influence comes from listening to fusion. That and different weird time signatures. All those weird syncopated drumbeats have affected the way I feel things, as opposed to being a four-on-the-floor rocker. Not that I don't love four-on-the floor, but the time-signature thing definitely entered our music from listening to Jeff Beck and John McLaughlin, and to jazz in general.

Can you point to a specific example of an odd time signature in your work?

A great example is a song like “Van," from [1987's] All. I don't know what time signature that song is in, but it's kind of out there. [Editor's note: It's in 7/4.] On the other hand, it's not so crazy—it's not math rock, but basically a riff that you can sing.

How do you work out your guitar parts?

There's a song on one of the All records called “Mary" that's a good example. What I had to start with was basically a simple four-note pattern that could have been played on the bass [sings the pattern], and then I put a vocal melody over it. So what I was trying to do was figure out notes to complete it, to make larger chords out of the whole thing. It's probably a crude form of orchestration—very crude. [Laughs.] It's like, “This instrument is playing this note and that instrument is playing that note. We might have an orchestra!" So that's how it happens in my head. I'm just looking for a place to bring a note or two into a chord that will expand what I have it front of me. I'm not using music theory. I wasn't taught that way. I'm an ear player, but I'm strong on hearing harmony notes that can fill out spaces into something interesting.

You might not be using theory, but you did study classical guitar. Talk about that experience.

Right before I turned 21, I decided it was time to actually learn how to play the guitar. I had just heard a Julian Bream record, and I sold all my electric guitars and bought a classical. I spent a year-and-a-half in the shed, neck deep, taking lessons and learning how to play classical guitar. I was going to try to go to a conservatory, but the Descendents thing happened and I got waylaid and here I am.

Stephen Egerton's Gear

GuitarsMusic Man Axis

Music Man StingRay

Dan Armstrong

Amps

Blackstar HT Stage 100 with HTV-412 cabinet

Effects

Danelectro Spring King

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball 2220 Power Slinkys (.011–.048)

Ernie Ball Heavies .94 mm

How has your classical guitar phase informed your work as a rock musician?

What probably affected me the most is the ability

to control all of the variables across the fretboard,

like how to play only the strings you want in a chord,

so that the notes you're trying to avoid don't ring out in bad ways and clash harmonically. Classical guitar really helped me with that, and it made me think in real terms about my timing.I didn't have good or bad timing before I started playing classical guitar, but my timing became very good once I got into really thinking about rhythm and practicing with a metronome. I made a lot of progress in a short amount of time, but my classical has been sitting in a closet ever since. I pull it out maybe every five years and go, “Whoa, I still have it."

You live and work in Tulsa, Oklahoma, far from your bandmates. What's that like and how does it work?

This is where my wife grew up. We've been here 14 years. We wanted our kids to be near their grandparents, plus the cost of living is really affordable here. It's worked out quite well. We have pretty good ways to practice—a friend fills in on guitar for rehearsals in Fort Collins, where our bassist and drummer live. Our singer lives in Delaware. I'm also kind of a studio geek and prepare things for everybody to practice to. Then when it's time to tour, we fly in and it's so great to see buddies and rehearse together.

On the new album, on songs like “On Paper," you solo in a concise and economical way. Are your solos improvised or pre-composed?

It's a mixture. On a classic song like “Clean Sheets," I worked that solo out. Again, it kind of refers back to what I always say about Jeff Beck's playing having a lyrical quality. It's all about making a guitar solo that a normal person can glom onto and understand. On [All's 1989 track] “She's My Ex," I do the same thing.

Thirty years down the road with the Descendents, Egerton says, “an interesting fact about the band, which is touched on in some of our recent songs, is its sheer longevity. The bass player and I met in junior high school and have been hanging out ever since. With Bill and Milo, it's pretty much the same." Photo by Kevin Scalon

On other songs, I might mix things up—do part of a solo in a very plotted-out way and leave the rest of it open to improvisation. It's a matter of experimentation. I'm not much of a scale guy, although I play a lot of scales as a practice thing. It's a wonderful way of keeping up technique and staying limber, like dribbling for a basketball player. But I don't think about scales when I'm actually playing. I'm just playing a song at that point.

Do the solos vary live?

Whatever way the solos turned out on the record, I usually play them the same live. My solo on “Everything Sucks," for instance, was improvised at the time, and I learned it and play it live.

Except for the gray hair, or lack of hair, this could be a shot from a punk rock show circa 1978, but it's from an April show at the Standing Room in Hermosa, California, where the band played their first hometown gig in nearly two decades.

Photo by Lisa Johnson

You produced the new album with drummer Bill Stevenson.

I'm neck-deep in that stuff. I record a lot of other bands, and like I said, I do TV shows as well. Bill and I both mix and master. Much of what I know I learned from Bill. For many years we did our albums on tape and had engineers working with us. Then, starting with Everything Sucks [1996], we tracked the album entirely ourselves—just the two of us, as far as engineering went. And then we had that one mixed by Andy Wallace [Run-D.M.C., Slayer, Jeff Buckley]. That was an awesome experience.

For the new album we used engineer Jason Livermore. He set up the drum mics and got us great drum sounds. I record the drums because I tend to mostly produce the drums—a glorified engineer role where I'm suggesting parts and critiquing performances.

For the longest time Bill recorded the guitars, but at a certain point I was able to just do it on my own, without another engineer, using Pro Tools. Bill recorded the vocals on the latest record, and he and I did a lot of the editing together. I did some mixing in the beginning, but in the end we went with Jason Livermore again, who's a fantastic mixer. I taught him. [Laughs.] He did the mixing, because when you work on an album, you're probably too close to it.

You get some pulverizing tones on the record, especially apparent in the spots where there's only guitar, like the intro to “Testosterone." How did you record the guitars?

There's a blend of miked and direct guitars on this album. When I recorded the guitars down here I did them just direct using an amp simulator, and I later sent them into [Livermore's studio] the Blasting Room. Ribbon mics are big in our camp, and we used a Beyerdynamic M 160.

How do you decide whether to go direct or mike the amp?

It's usually blended together. The direct tracks tend to be very midrangy, with not a lot of air around them. Sometimes a miked track can broaden that, or sometimes we like to use a little DI box behind a miked guitar. It also depends on the amount of overdrive. Some of the tracks are a bit more overdriven than others. Frank Navetta, the original guitar player, tended toward a cleaner sound, like a Twin and a Tele, as opposed to a lot of his contemporaries, who were Marshall guys. I like to mix it up a bit.

Some of your new songs, like “No Fat Burger" and “Comeback Kid," are about the consequences of getting old. Can you reflect on what it's like to have been in a punk band for 30 years?

An interesting fact about the band, which is touched on in some of our recent songs, is its sheer longevity. The bass player and I met in junior high school and have been hanging out ever since. With Bill and Milo, it's pretty much the same. They were best friends in high school.

When the band started, there was no future in punk rock and there was no business structure or even any money in it. If you were lucky you got to play parties. You played punk for the sheer enjoyment of it and for the friendships. A lot of bands broke up when their friendships ended, or when the members got jobs.

YouTube It

Stephen Egerton and the Descendents prove that old punks don't fade away or burn out in this live performance from 2013 in Gainesville, Florida. On the first number, the title cut from their 1996 album Everything Sucks, Egerton interrupts his cannonballing rhythm attack for a solo at 1:40, letting some single notes ring out and resolving with a bent-string climb.

We still play together because we're great friends and because the music is absolutely essential to us. It's how we express ourselves completely, and doing it together is a high comfort zone for us. Generally speaking we don't put out too many albums. It's usually several years and sometimes even a decade or more between them. The albums reflect where we are at the time—no one's just sitting around trying to write hits—and to us the songs are very personal. “No Fat Burger" is relevant to a bunch of guys who are getting older.

It's so cool to have people that are still interested in our music. There isn't a day that goes by that we don't go, “It's weird that we have so many new people checking us out." We're stoked that people still care and that we're able to do it. And that we've survived. We've had some major health issues with some of our guys. Karl had a heart attack some years ago and Bill is the Million Dollar Man. He's been through the ringer with all kinds of stuff: a huge blood clot that almost killed him, a brain tumor. He's just been slaughtered, but is up there kicking ass like never before.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)