Gary Rossington—the guitarist who inspired Lynyrd Skynyrd’s song “That Smell” and then played the hell out of it, with sailing, melodramatic feedback and a corpulent, grizzly-bear tone decorated by squealing pinch harmonics—died on Sunday, March 5, after at least a decade of coronary issues, including bypass surgeries and a reported heart attack in 2015. Rossington, who held the reins of Skynyrd ’til the end, was the band’s last surviving original member.

The 71-year-old was also the primary slide guitarist in the foundational version of the Jacksonville, Florida-birthed group, playing the distinctive chirping introduction to their iconic “Free Bird,” as well as the muscular solos on “ Simple Man,” “Comin’ Home,” “Tuesday’s Gone,” “Call Me the Breeze,” “Gimme Three Steps,” “ Cry for the Bad Man,” “Workin’ for MCA,” “On the Hunt,” and their version of the Jimmie Rodgers classic “T for Texas,” among many other memorable, influential performances.

Rossington’s tone was always like a boxer’s fist—strong, calculated, consistent—regardless of the gear he played, but the core of his sonic formula was a Gibson Les Paul Standard plugged into 160 watts of Peavey Mace or 100 watts of Marshall. In fact, Rossington boasted in a 2017 PG interview with journalist Joe Charupakorn that he played his 1959 Les Paul on every Skynyrd recording and show from the band’s inception until 1977. (Although live videos of the band in the mid ’70s also show him with a two-humbucker SG slung around his shoulders.)

In Skynyrd’s nascent years, that Les Paul was his sole instrument. “Early on, we didn’t have the time to change tunings onstage, plus I only had one guitar back then, so I learned to play slide in standard,” he told me in 2015. To raise the action for his glass slide, Rossington would insert a pencil above the first fret on his guitar’s neck. He was proud that “my ’59 Les Paul, Bernice, is in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame sitting right next to Duane’s and Clapton’s guitars. They were my two biggest idols coming up, so having my guitar right between theirs is great!”

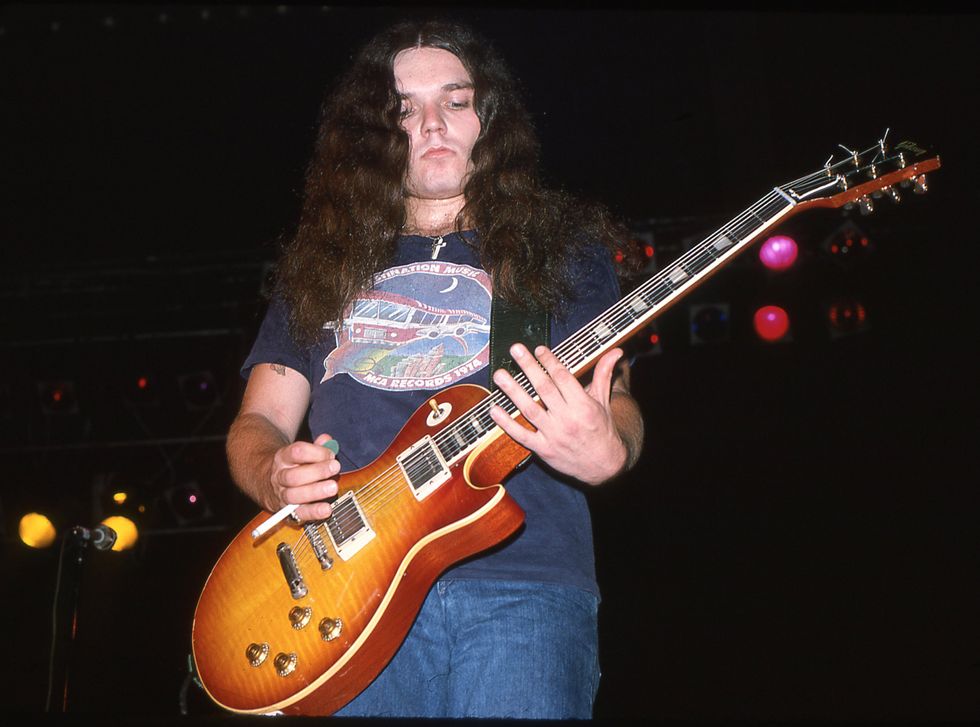

Rossington onstage at New York City’s Beacon Theatre in 1976, the year of his infamous auto wreck and the success of the live One More from the Road and “Free Bird.”

Photo by Frank White

Over the decades and the trials—brawls with Skynyrd’s mercurial leader Ronnie Van Zant that once left him with glass-shredded hands in the middle of a European tour; the terrible October 1977 plane crash in Mississippi that killed Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines, singer Cassie Gaines, and three others, and left Rossington badly injured; the booze-and-drugs-fueled car crash that inspired “That Smell”; the challenges of addiction and recovery; and the rising and falling tides of the music business—Rossington survived with his everyman charisma and chops intact.

He was born in Jacksonville in 1951, and his father died in the Army soon after. Initially, Rossington, who was inducted in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2006 as a member of Skynyrd, wanted to be a baseball player, but that changed with the arrival of the Rolling Stones and when he fell in with Van Zant, who became a father figure. They formed their first band together in 1964 and evolved into Skynyrd in 1969. The debut, Pronounced ’Lĕh-’nérd ’Skin-’nérd, was released in 1973 and contained “Gimme Three Steps,” “Simple Man,” “Tuesday’s Gone,” and “Free Bird,” although the latter did not become a hit until the 11-minutes-plus version on 1976’s One More from the Road was released to FM radio—forever launching “Play ‘Free Bird’” as a call for Skynyrd fans and wiseasses alike.

Rossington’s tone was always like a boxer’s fist—strong, calculated, consistent—regardless of the gear he played.”

I grew up listening to Lynyrd Skynyrd and had tickets for their Street Survivors tour at the New Haven Coliseum. It would have been my first time hearing the band live, and I was thrilled. I was also crushed when the news of the plane crash spread four days after the album’s October 17 release. I did catch the Rossington-Collins Band, which Rossington formed with fellow Lynyrd Skynyrd guitarist Allen Collins in 1979, along with Skynyrd’s bassist Leon Wilkeson and pianist Billy Powell, in 1980 at the Springfield (Massachusetts) Civic Center, but Rossington had broken his leg the day before and the vibe was, understandably, off. Seven years later, after Skynyrd reformed with Johnny Van Zant as vocalist, I caught their fiery, inspiring performance at the Centrum in Worcester, Massachusetts. Hearing the tones and visceral playing that Rossington evoked from his guitar, I immediately decided to buy my first Les Paul.

Almost 20 years later, when I was able to interview Rossington for the first time, I was inspired again—this time by his candor, humor, and humility.

When we spoke about recording “That Smell,” still one of my favorite rock songs, Rossington seemed delighted recalling that day in the studio. “It was perfect,” he said. “My guitar sound was hot, with the feedback. It was everything I wanted.”

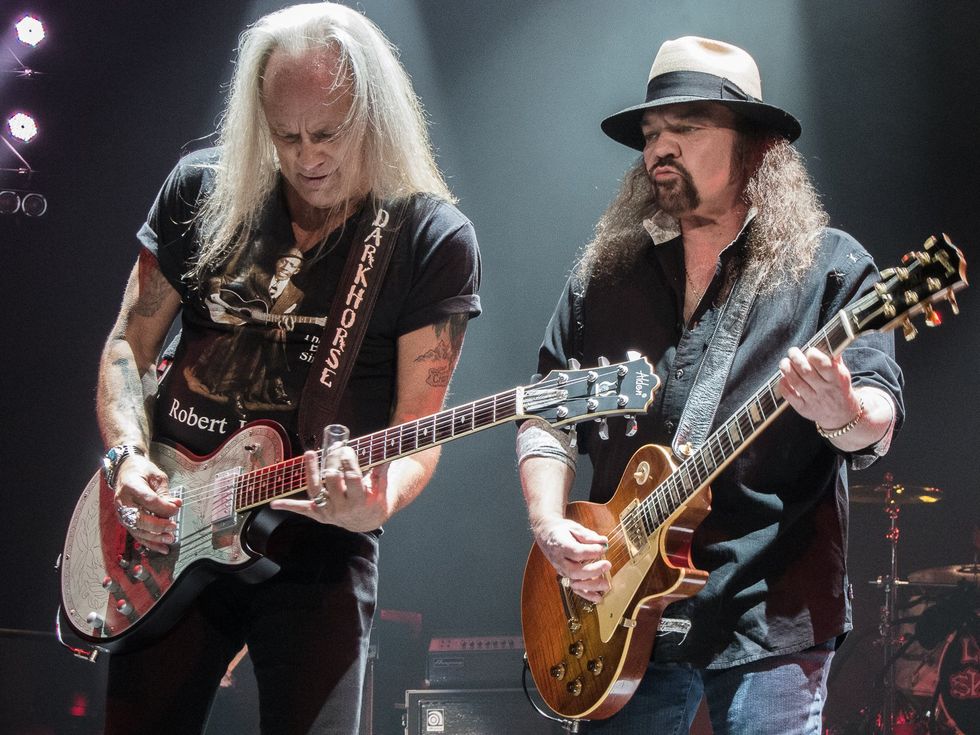

Rossington takes part in a Lynyrd Skynyrd tradition, trading licks, with one of the current lineup’s other guitarists, Ricky Medlocke, who is the former frontman of Blackfoot and was the drummer for Skynyrd in their earlier days.

Photo by Steve Kalinsky

He also talked about the experience that inspired Ronnie Van Zant and Allen Collins to write the song. “I was out of control,” he said of hitting an oak tree and a house with his brand new Ford Torino while on a bender in 1976. “I did get in a car wreck, but we got a good song out of it.” Rossington was so wild that there were times when his bandmates, no slouches in indulgence themselves, were sure he’d kill himself.

“Eventually, I learned that drugs are just horrible for you,” Rossington observed, “but that’s the way it was in rock ’n’ roll in our time. I can’t do any of that stuff now. I’m not in such great health. I’ve had some heart problems, and I’m on the straight and narrow. It’s a lot better than being fucked up all the time, and I thank God I made it through those days.”

“We loved Cream and Clapton’s style, and all the guitar players with the British bands—Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and also Hendrix.”–Gary Rossington

Decades later, the plane crash still hung over Rossington’s conversations about Lynyrd Skynyrd like a specter. He rarely mentioned it directly, preferring to complete relevant sentences with terms like, “until, well, you know…” or simply pausing to skip a beat.

But the guitar hero was delighted to talk about his own guitar heroes, who profoundly influenced him and generations of players, just as Rossington would influence generations in his own lifetime. “We loved Cream and Clapton’s style, and all the guitar players with the British bands—Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and also Hendrix,” he recalled. “But mostly it was Clapton, because he was so good, and he played more of the kind of blues we were raised on. I grew up listening to him and hoping to be that good one day. Of course, I never made it, and I never got near Hendrix, either. I don’t know if anybody will ever be as good as Hendrix again.

“And Duane and Gregg were big deals to us. They inspired us before they were the Allman Brothers. We would go see all the bands they were in while we were growing up. The Allman Joys played a lot in town, at clubs and teenage dances. Duane and Gregg were already great even then, and you could see Duane get better on guitar every week or two. Plus, they were older than us doing exactly what we wanted to do— they were driving and smoking and had long hair and were out of school. They were as cool as sliced bread!”

His current Lynyrd Skynyrd bandmates offered this announcement of Rossington’s death, on social media. “It is with our deepest sympathy and sadness that we have to advise that we lost our brother, friend, family member, songwriter, and guitarist, Gary Rossington, today. Gary is now with his Skynyrd brothers and family in heaven and playing it pretty, like he always does.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)