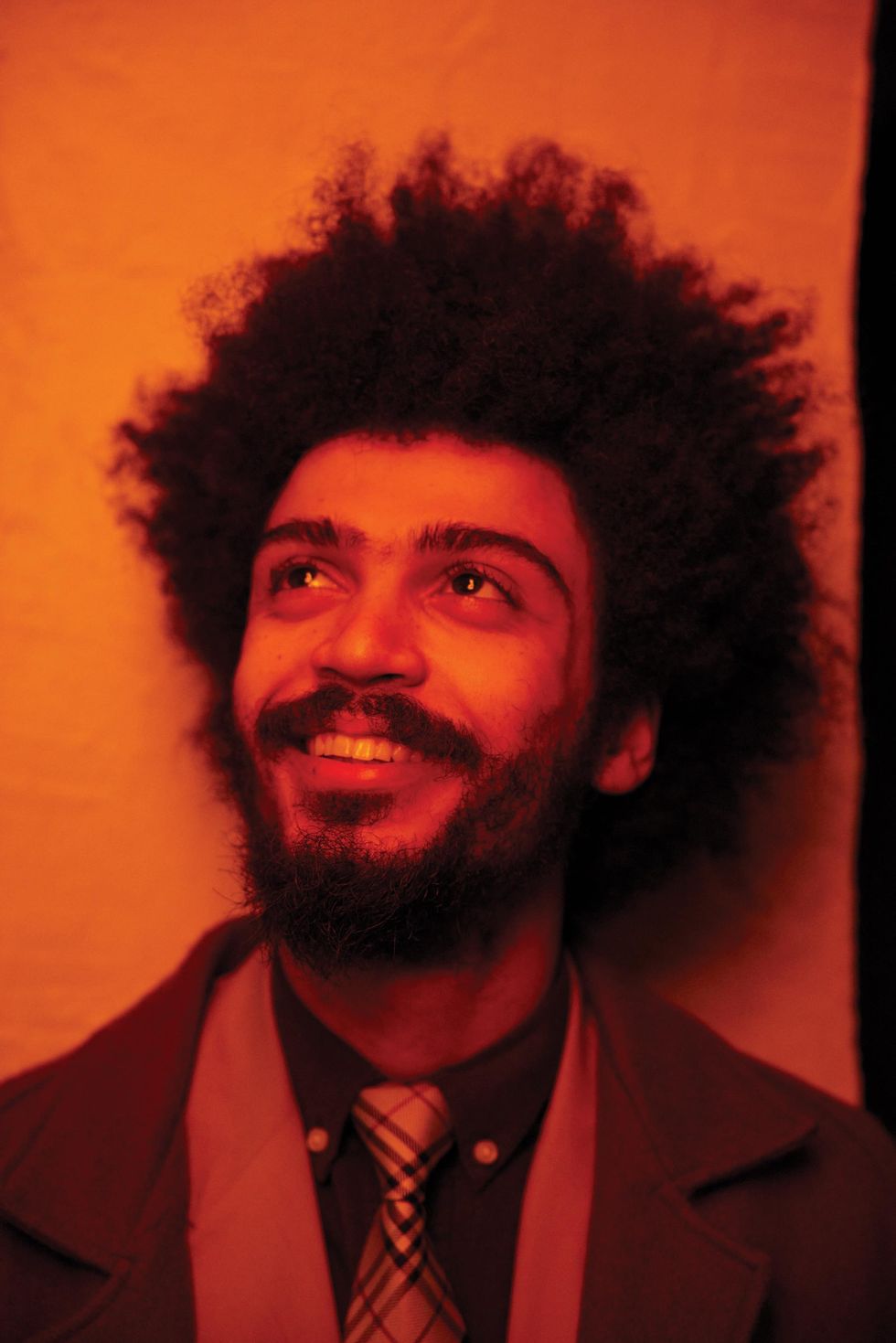

Yves Jarvis—born Jean-Sébastien Yves Audet—is allergic to being complacent. “I don’t like to tune my guitar live,” the Canadian-born singer-songwriter says about his almost irrational fear of creative ennui. “I don’t even have a tuner. I like to make my entire set in the same tuning—that’ll be an alternate tuning, it’ll be something random. I force myself to find a way to reinterpret all my songs in the same tuning.”

In fact, Jarvis chooses one tuning for an entire tour. He does that although each of his songs first comes to life—as it is being written and recorded—in an original song-specific tuning. But tunings, at that early stage, are just compositional devices. Once a song is recorded, its tuning is forgotten, and when it’s time to hit the road, he relearns each song in the new tuning chosen for that tour. If he decides to reprise an older song, he learns it up yet again in that new tuning as well.

All that learning and tuning keeps Jarvis on his toes, which he finds exciting. “I get stuck in too many patterns, too many shapes, so I throw myself off,” he says. “I love being thrown off.”

Yves Jarvis - "Bootstrap Jubilee"

What was the tuning Jarvis used on his recent summer tour? Good question.

“I’m in D–A–D-something, that’s for sure,” he says. To figure out the rest, he brought his laptop—we spoke via Zoom—into another room with a piano. “Someone once asked me about my tuning at a show, and people think I’m being coy, but I actually don’t know what it is. I know how to get there with a guitar, but I don’t know what the notes are.”

He tuned up his guitar by ear, sat at the piano, and figured it out. It didn’t take long. His summer 2022 tuning was D–A–D–E–A–C#. It won’t be that again.

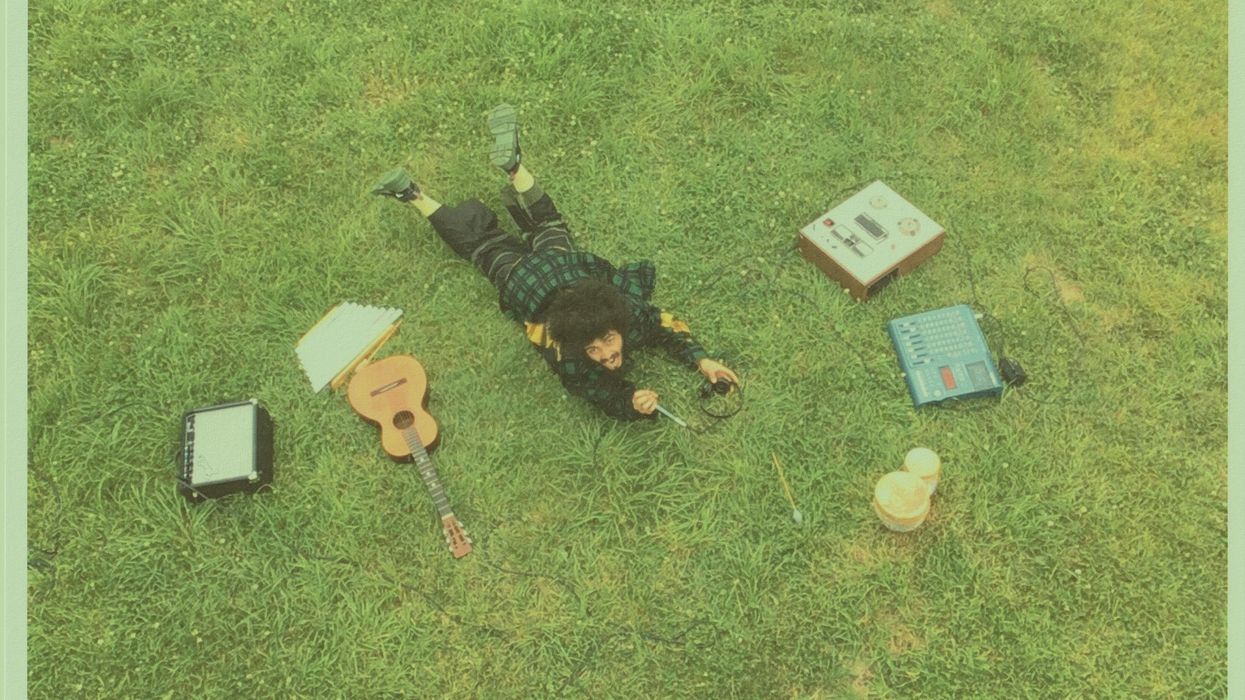

That type of unpredictable spontaneity is how Jarvis does everything. That explains his addiction to cheap gear, his aversion to pedals—which he never uses—and why he didn’t even bother with an amp on The Zug, his latest release, which he recorded at ArtScape, the artist-friendly place he was living in at the time. “It’s a subsidized-for-artists condo in Toronto [where rents are sky high] and the building is full of artists,” he says.

Yves Jarvis recorded his fourth album, The Zug, at Toronto’s ArtScape, a subsidized living space for artists. The Zug is a masterclass in lo-fi guitar orchestration on a limited budget.

The Zug is Jarvis’ fourth release since 2016 under the moniker Yves Jarvis (Jarvis is his mother’s maiden name), and prior to that he released the critically acclaimed Tenet under the name Un Blonde. In 2019, he was longlisted for a Polaris Music Prize. The Zug is an intimate collection of songs, and that means intimate, as in up close and personal. The vocals sound as if he’s whispering in your ear and letting you in on a joke. Jarvis plays all the instruments himself, and that includes an array of alternative timbres and sounds. “Noise was an issue,” he says about the challenges of recording in a condominium. “Nevertheless, I was playing the drums with chopsticks, but that was for feel, not for noise suppression.”

Chopsticks aside, most of the effects on The Zug were done with guitar. On songs like “At the Whims” and “Enemy,” Jarvis employs dramatic swells and backwards-sounding leads, which complement the more subtle fingerpicking and gentle warbles on “Prism Through Which I Perceive” and “You Offer a Mile.” The album is also a masterclass in lo-fi orchestration. Check out “Why” and, especially, “Stitchwork,” with its string-sounding pulses and layered effects that are, in a simple way, almost Beatle-esque. All done with guitar, and on a very limited budget.

But lo-fi also has its share of challenges. “I need to invest in a vocal mic because it would be nice to not have to do 100 takes of the same thing,” Jarvis says about his idiosyncratic multi-layered vocal sound. “It started out as an aesthetic thing, being that I wanted to create this texture that was inspired by D’Angelo—many voices at once, perfectly stacked. But then, layering became a necessity because I was not pleased with the single takes. In order for all the nuances of my voice to translate to the recording, I have to have multiple layers.”

“But I’m not averse, at all, to effects. I have just always gotten off on forcing myself to simulate my own effects.”

That labor-intensive effort is how Jarvis gets his guitar tones as well. As mentioned, he doesn’t use pedals. “I can’t imagine looking down at a pedalboard, frankly,” he says. “I think I’m getting there in my growth as an artist where I see the potential of using pedals. But that’s precisely the problem—too much potential. Although I see where I could benefit with experimenting with new tech.”

The distortion sounds were created by running his guitar into an old TEAC reel-to-reel machine—and a single, loved, beaten reel of tape—and then into the open-source DAW Audacity, which is ultimately where everything ends up. “It’s nice to manipulate sound with such an analog piece,” he says about his tape machine. “I also like stretching and distorting the tape. I’ve never really used a different reel of tape. It’s been the same reel on there for years and years and years, and the degradation of that reel has really played into the sound of the guitar. I think the best example of it on the record is at the end of ‘What?’ That electric guitar solo is the most quintessential sound of my TEAC, for sure.”

But Jarvis’ aversion to pedals doesn’t come from some purist notion of tone craft. Rather, similar to choosing a new tuning for each tour, he sees limitations as a creative tool, albeit with ideological strings attached. “Constraints are very helpful for me,” he says. “I don’t like options—especially in our culture today where everything is custom. You go into a restaurant, and you can customize your order, I hate that. Tell me what to get, or don’t tell me what to get, but constrain me. Two options are all I need. That’s where the experimentation comes from—from some sort of physical parameter like playing percussion backwards, for example, so that the feel is different—just little things like that. But I’m not averse, at all, to effects. I have just always gotten off on forcing myself to simulate my own effects.”

Yves Jarvis’ Gear

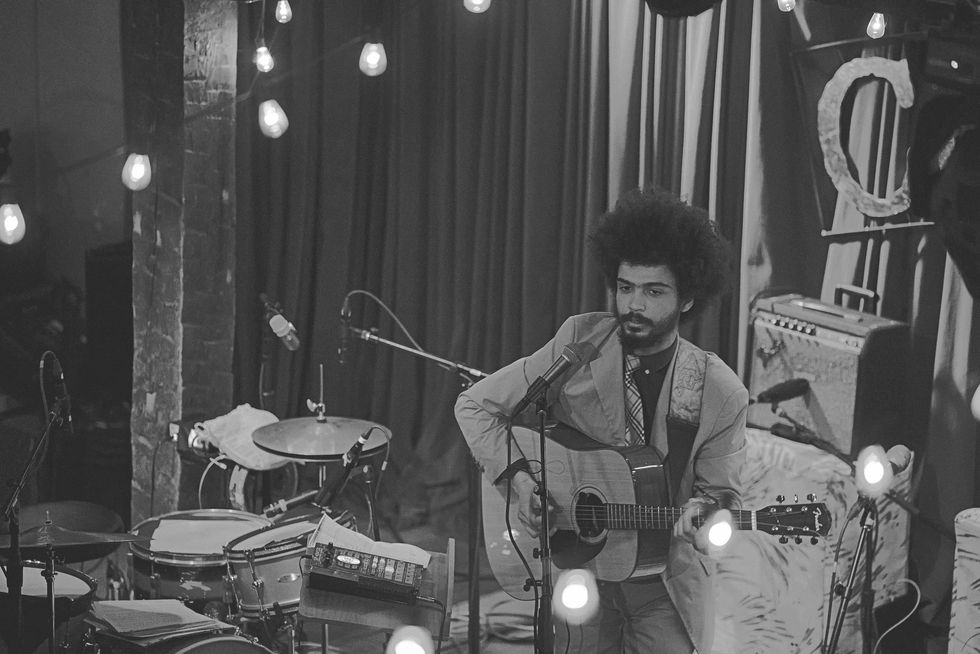

Yves Jarvis plays solo acoustic at the Colony in Woodstock, New York, in February 2022. His acoustic is a Fender he bought for $50 in Gravenhurst, Ontario.

Photo by Michael O’Neal

Guitars

- Fender acoustic

- Hondo Formula I

- Yellow S-style

Recording/Sound Manipulation

- Tascam Portastudio 424 MkIII

- TEAC Reel to Reel

Strings

- Any brand, heavy gauge, usually starting with a .012 for the high E

Jarvis’ methods for simulating effects aren’t completely outlandish. His reversed guitar sounds—which you can hear on The Zug’s “Enemy”—are done with a whammy bar and riding his guitar’s volume knob. Some of his delay-like effects are done the old-fashioned way: manipulating tape as it passes from one head to another.

Yet despite his embrace of the reel-to-reel, his first love is a Tascam Portastudio 424 MkIII multitrack cassette recorder. “I’ve gone through maybe a dozen Tascam 424 MkIIIs,” he says. “That’s the only piece of gear that I know about, which is crazy. Ten years ago, I got them for $100 bucks a pop every time. Now they’re $1,000 bucks.”

Another outgrowth of his quest for unpredictability is how Jarvis uses a capo, which he often places high up on the neck at around the 8th or 10th fret. He prefers it like that, with the strings taut, similar to a smaller-scale instrument like a ukulele or mandolin. It opens up a very different world of harmonics and other sonic possibilities, although he has more pedestrian reasons for using a capo, too, which is the difference in how he sings live versus the studio.

Once Jarvis records a song, its tuning is forgotten. When it’s time to hit the road, he relearns each song in a new tuning chosen for that tour. His 2022 tuning was D–A–D–E–A–C#.

Photo by Michael O’Neal

“I like my voice to be like a whisper on recordings, but live I like to really sing,” he says. “That’s the thing: The textural qualities that I’m looking to lay down on the record are not at all similar to what I’m trying to do live. Live, I like to be clear-eyed vocally, and with recordings I want it to be more of a whisper. That’s the main impetus for the capo, too. I usually perform the song much higher than the recording—although I also use a capo because I usually use pretty shitty gear—and I like the guitar to have that twang, that sharpness of a mandolin or something very taut.”

In Jarvis’ telling, that sharpness can take on a somewhat mystical feel as well. He’s searching for a certain synchronized resonance between his voice and the instrument’s natural vibrations. “I’m definitely making an effort to match those resonances,” he says. “The guitar on the chest, the guitar on the belly, and amplifying that, and amplifying each other. I feel that is a very deconstructive process in the studio, and then live it’s something that I’m trying to have as a unit, a package of songwriting.”

And just in case you think Jarvis doesn’t do enough to avoid becoming complacent, his instruments of choice are usually low-budget starter guitars, which, obviously, come with their own issues and quirks.

“I’m excited to plug in a cool guitar that I just got back. It’s a guitar I’ve had since I was a little kid: an electric Hondo. It’s an Explorer shape. It’s red and it’s got all these stripes on it.”

And his electric?

“I’m excited to plug in a cool guitar that I just got back,” he says. “It’s a guitar I’ve had since I was a little kid: an electric Hondo. It’s an Explorer shape. It’s red and it’s got all these stripes on it. I left it at my buddy’s when I lived in Calgary as a kid, and then he had it for 10-plus years. He fixed it up for me. He just gave it back and it sounds amazing. That’s a guitar that I’m really excited to have back because it’s just so dirty and gritty and sounds just straight off Neil Young’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, which is a beacon for me in terms of electric guitar tone.”

It’s not a gimmick. Jarvis is a unique, forward-thinking artist, and, ultimately, the tricks he employs make for engaging, compelling music—music that takes on new life with every retelling. “Because of the improvisational nature of the production, relearning my music and restructuring it in a more traditional format is really an exciting thing for me,” he says.

It’s exciting for his listeners, too.

Yves Jarvis - Full Performance (Live on KEXP at Home)

In this intimate acoustic performance recorded for Seattle’s KEXP radio, Yves Jarvis plays five songs with assistance from his faithful capo.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)