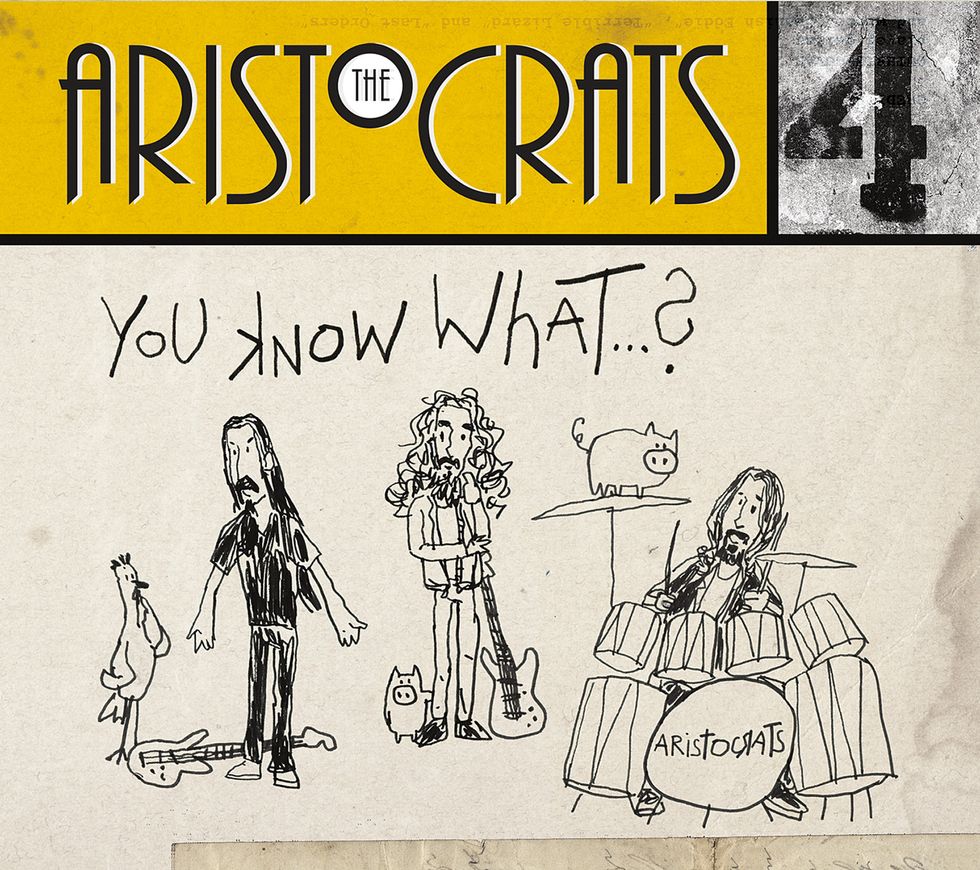

Players and listeners alike commonly express the sentiment that guitarists cannot live on shred alone—and as an internationally-hailed shredder, English-born guitar virtuoso Guthrie Govan might just be the poster boy for that rule. In his trio the Aristocrats, which released their fourth studio album You Know What...? on June 28, he gets every sound, mood, and noise out of the guitar, with deft placement of those Yngwie-on-fire licks. He’s mindful, nimbly and playfully roping bridges between modes of opposing musical poles to create some united territory all his own. For example, the second track “Spanish Eddie” goes from flamenco/metal to country-twanged blues, showing you how the styles make a good pair in a way that makes it seem silly to have kept them apart.

For someone who played his first gig at age 5—“some Chuck Berry and Elvis songs, ’cause that’s what floated my boat”—his “virtuoso” title isn’t a surprise. What is refreshing, however, is Govan’s very humble disposition. It’s worth noting that at the age of 20, he was offered a record deal from Shrapnel Records, and, feeling validated, turned it down as he felt the label’s primary audience would be overly interested in his musical athleticism. Then, after dropping out of Oxford, he spent some time working at a McDonald’s, before realizing he could make money more happily through transcribing, teaching, and performing. Since, he’s worked with Asia, Steven Wilson, Jordan Rudess, and Hans Zimmer.

His influences include early Elvis, Joe Pass, Steve Vai, and Frank Zappa, but from speaking with him, it’s clear he takes lessons from music of all kinds. When writing for the Aristocrats, he says, “I spend quite a time worrying about how I can convey as much harmony as possible with just one guitar and one bass. It sounds like someone’s playing bass and someone’s playing the melody, but chordally there’s interesting stuff going on.”

Govan has said that he can’t enjoy being a sideman in the long-term, but his discography doesn’t say “frontman” either. With bassist Bryan Beller and drummer Marco Minnemann, the Aristocrats is a purely collaborative triumvirate of musical superpowers—all three are highly skilled multi-instrumentalists. “I think a lot of the readers of your magazine would be scared if they saw what Marco’s picking hand could do,” Govan says, laughing. “We find it’s more fun to write for each other rather than to write selfishly. Bryan always has a good time writing guitar parts, knowing that I will have to deal with them. And I have fun writing bass parts knowing that Bryan will be capable of reproducing them.”

The approach is childlike, and the result is slightly mind-blowing. Read more about Govan’s and the Aristocrats’ process below.

So you guys self-produce, the three of you together?

Yeah, it’s something we pretty much settled on from day one. We had this kind of mental image of three musketeers and everyone having equal input, from the business side of things to the writing. Now, I live in London, and when the band started Bryan [Beller] lived in Nashville, and Marco [Minnemann] lived somewhere near L.A. or San Diego, so rehearsal on a regular basis was never going to be a practical thing. When we make an Aristocrats album, each of us will write three tunes and make a demo, which is pretty detailed and specific. I’ll play bass and guitar, and program the drums, then send the MP3s out and the other guys do the same—and we all try and absorb the demo versions as well as we can. Then we book a studio and go in there for 12 days, and trust that we’ll be able to knock these songs into some kind of shape because we’ve done so much preproduction. And whoever wrote the song, by default, gets to be the alpha producer for that piece of music.

For past releases, you’ve discussed being hesitant about overdubbing. How did you approach that for this record?

For this album, I decided, “I’m going to be really brutal about this, I’m going to make sure that at any point in any one of the three tunes I’ve written, there will be one guitar part. It should be something that I can reproduce accurately live.” Marco kind of went to the other extreme and just said, “I want to do something really cinematic and overdubbed and make it sound really produced.”

So I guess he wrote “Burial at Sea.”

Yes. There’s all kinds of stuff in that one. There were certain sounds he actually had on his hard drive before we went into the studio. He was like, “Well, I’ve done some sound design stuff and I’d like to weave this into the arrangement.” He records a lot of the sounds in his life. I think there’s some weird gurgling sounds in “Burial at Sea” and it’s actually him with his iPhone recorder just like walking near the sea and recording these creepy noises. We played that one to a click with all the crazy synths and sampled sounds.

Do you like to record to a click usually?

We do that on a case-by-case basis. In some situations, there’s something tyrannical about the click and it can hamper the way the groove actually wants to feel. Then something like “Spiritus Cactus” wants to feel quite robotic and mechanical—that’s part of the appeal of it. “The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde” was more organic. As I recall we didn’t have a click for that one.

Do you have a favorite song from the album?

It’s too early in the tour for me to comment. We really start learning the songs once the album is complete. Our goal is not to play the songs exactly the same way every night, but to have a little leeway to allow fortunate accidents to happen, and then remember which experiments worked and which ones backfired. Then particularly over the first month or so of touring, these songs reveal themselves to us and let us know how they really want to be played.

What part of the process do you most enjoy: the writing, recording, or touring?

I like to think of us as an old-school band. Whenever we finish the record we will tour like maniacs. So knowing that’s how we operate, I think we all have a slightly different mindset in the studio, compared with, for instance, the experience I have if I’m recording with Hans Zimmer. I recently made a bunch of weird noises for the soundtrack to the new X-Men movie.

TIDBIT: The Aristocrats self-produce all of their music. Each member writes three tunes and makes detailed demos of those songs before the group steps into the studio.

There’s all kinds of guitar stuff on there and nobody would ever guess that there’s a guitar. But with that process, I’m in the studio, and I can try all of these absurd things knowing that no one will expect me to go out onto the stage and replicate the noises I’m making. That’s a really fun side of studio work, where you know the studio is a self-contained thing. With the Aristocrats, the end goal is always—we want to make the best album we can make, but then we want to take it out on the road. Really every step of that process is fun.

Are you happy with how the band’s evolved over time?

Yeah, it’s been really positive the way things have evolved. On Tres Caballeros we were all kind of tentatively tipping our toes into the water of overdubbing, and I think on the new records there are more extremes. In some cases, the songs went right back to the basic approach of the raw trio, and the more overdubbed songs are hilariously overdubbed. But specifically with this band, we wouldn’t want to do something if we thought it might damage the story arc of what we’ve done so far. We’ve always had some degree of this telepathic mutual understanding, and when we play together it feels like we’ve known each other for longer than we have. One of the purposes of this band is to try and celebrate that. It’s fun, it’s an ongoing process, and it doesn’t feel like we’ve reached the end of anything yet.

Shifting gears a bit, what’s the difference between the gear you use live and in the studio, if there is one?

Maybe 70 percent of this album was recorded with the same gear that I would use live, like my Charvel signature model. I only brought one on tour, if anyone’s curious, and it was the ash-bodied version which sounds a little Strat-ier through the Victory V30 head. And it’s the MKII V30, which has a little button on the back so you can switch between the new voicing and the old voicing. Mostly I was using the new voicing, which maybe sounds 10 percent more American to my ears, and a little differently focused in the midrange. But something like “Bonnie and Clyde” is the old voicing of that amp.

Guthrie Govan’s Charvel signature models are baked in an oxygen-free oven to zap moisture for more stability. His current favorite has an ash body. “Every kind of wood has a sonic thumbprint which is recognizable to me,” he says. Photo by Danny Work

Any other gear you feel passionately about, in or out of the studio?

We spent a long time designing the [Charvel] guitar in such a way that it would be able to cope with all kinds of different musical situations, so that guitar can do a Steven Wilson gig, a Hans Zimmer gig, an Aristocrats gig, a guitar clinic, or whatever. I did play around a little more on this record. For instance, I now know I should acquire a Fender Jazzmaster. [In the studio] they had a really nice ’60s Jazzmaster and that’s what you hear on all of “Spiritus Cactus.” I also discovered that I really like Vox AC30s for a certain kind of clean tone. “Last Orders” has a thin Stratty-sounding pickup setting running into an AC30, which adds this warm roundness. I left the studio wondering why I hadn’t recorded more stuff using that kind of tone. Sometimes a different combination of gear will inspire you to imagine different things, whereas if you had started with your regular gear, these ideas might never have occurred to you.

I know you’re very sensitive to the woods your guitars are made of. Aside from the obvious, why is that so important?

There are two reasons to care about wood. One is stability, and one is tone. The guitars I use now, the wood is all being baked, or caramelized if you will—they put it in an oxygen-free oven to get rid of some of the moisture and kill some of the organic impurities that might be in there. It makes it more stable, which is really helpful if you’re touring a lot and hopping from one climate to another, rapidly and repeatedly. It’s nice to know that your neck isn’t going to mutate horribly. But also, every kind of wood has a sonic thumbprint which is recognizable to me. So sometimes if I hear a certain sound in my head, I can translate that into, “That’s a mahogany tone.” Almost like these woods have different vowel sounds, like they honk from a different part of some sort of imagined nasal cavity. I know this sounds strange. [Laughs.]

You’re regarded as a virtuoso by your peers. How have you come to be such a skilled player?

Everything I’ve learned has started with me hearing something and saying, “I like that. If I understood how to do that, I know how I would use it.” I’ve always been interested in just copying the sounds that I hear around me. Be it an album that I found in my parent’s record collection, or what the ice cream van is doing outside the house, or a police siren, or a bird song—I’ve always had that kind of parrot element. If I hear something, I want to be able to imitate it.

I’m going to wheel out my well-used analogy, which always crops up in guitar clinics: When you’re learning an instrument, you get to choose what kind of language you want music to become in your life. It can either feel like your mother tongue, or it can feel like a language which you learned at school. You learn English by copying sounds that you hear around you and then learning what happens in your life when you make each one of those sounds. I always wanted music to feel like English, rather than one of the languages I learned at school.

How did you learn to shred?

Once you’ve figured out how to play some new thing that you couldn’t play before, I’m a believer in maybe don’t reach for the metronome and crank it up immediately. Now see if you can play the same thing again but use fewer calories. Can you play the same thing again whilst, like, watching the TV, or thinking about something else? Can you do it so that you can play it a hundred times in a row without hurting yourself? If you prioritize stuff like that, then you end up with good technique. And then one day when you need to do it at twice the speed, your body kind of knows how. Nobody ever practices how fast they can talk. People spend their lives using languages to say stuff that they want to say. And then one day when they get excited, and they naturally want to speak quicker, they find that they can do it.

You’ve played with a variety of people. What’s guided your career choices?

My business plan from day one has always been, say yes to things if they’re interesting, or if I think I’m going to learn something by taking on any given musical challenge. But I try to hang on to that kind of childlike thing. I play because it makes me feel complete. I enjoy just expressing myself through playing—everything else is just a detail. Which is not a great attitude, I wouldn’t recommend that attitude to any readers, but it’s what feels right to me, and you’ve got to be yourself, right?

Guitars

Charvel Guthrie Govan signature model (ash body; two on tour: one in standard tuning, one in drop D)

Amps

Victory V30 MKII head

Victory 2x12 cabinet (with Celestion Vintage 30 speakers)

Effects

Fractal FX8 for effects processing and amp-channel switching (“Just to clear up one common misconception," says Govan, “all overdrive tones are generated by the amp itself, not the Fractal.”)

Strings and Picks

D’Addario NYXL strings (.010–.046 sets with a .052 substituted for the lowest string on the drop-D guitar)

Red Bear Guthrie Govan signature flatpick

Is there anything you do to find creative inspiration?

Well, I think the music that comes out of you is invariably a product of all the music that goes into you. You are what you eat—it’s the sonic version of that. I think whenever you’re trying to listen intelligently to something, find out what’s good about this unfamiliar genre of music or unexpected recording, it wakes up that part of your brain which is responsible for generating new ideas. It all incubates in your musical mind, and when it’s ready, the thing that you’ve taken from all that listening will reveal itself when the time is right.

For “The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde,” Bryan sent me a demo of that, and it was some kind of “super strat” guitar tone through a very overdriven amp, and I thought what kind of character can I imagine interpreting this melody that I’ve been sent. And for some random reason it just kind of came to me: This should be a ’70s guy with a Les Paul. That’s the character who would deliver this melody with authority. So I actually became that guy. I went into the studio with a Les Paul, and I never play Les Pauls. They sound great but I don’t feel comfortable playing one. So, perfect. I am going to very deliberately play this guitar, which will fight me, and I will have to fight it back.

Any modern guitarists you like?

I kind of tuned out a little bit from listening to guitar all the time. Partially because it reminds me of work. [Laughs.] I generally have more fun these days listening to stuff where the guitar isn’t such a feature. The last player I heard who really blew my mind was probably Derek Trucks. And I think quite a few years have elapsed since it was accurate to describe Derek Trucks as one of the new players.

So then what are you listening to?

I’m a big fan of Knower. They’re kind of Daft Punk with a jazz degree. Sometimes it’s fun to listen to Jacob Collier and work out how that’s even possible. [Laughs.] I’m a sucker for elaborate lavish harmonies and that whole Take 6 approach, and he’s really taken that to the next level. In terms of confusing music, Tigran Hamasyan is a lot of fun. There are elements of Meshuggah in there, Armenian folk music and everything in between. He’s fascinating. Oh, and Tipper. There’s a new Tipper album. He’s an electronic DJ kind of guy, but really good at sculpting noises that aren’t real instruments. And that’s perfect for me, to go back listening to something in a happily ignorant way because you don’t understand where the source of that sound is. Some of the electronic stuff really cheers me up.

I’ve heard you’ve had an interest in learning electronic production. How’s that going?

Yeah, still a work in progress.

What program do you like to use?

I’ve always been a Logic guy, but I wanted to create a little world that was separate from that, for when I want to think electronic thoughts, so I’m having a lot of fun with Ableton now.

Cool! What have you been working on recently?

Nothing that the public needs to know about. I’m still in that stage of just exploring and being a kid.

Seen here performing “Desert Tornado” from the Aristocrats’ 2013 record, Culture Clash, Guthrie Govan illustrates his breadth of technique, dropping in speed-of-light lines (jump to 2:22 to be amazed) between carefully placed harmonies.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)