The Lee Boys - "Testify" by Evil Teen Records

“Come on, man—I was freaked out,” says pedal-steel guru Roosevelt Collier of “hard rock gospel” band the Lee Boys. “I was, like, ‘John Scofield just left his coffee cup on my table. Nobody better touch it!’” Such are the pleasures of life when the incredible players from the sacred-steel circuit step beyond hallowed halls and into the gentile world. “I had the pleasure of him coming in my room for about an hour and talking about my background. We played together and, dude—it was sick.”

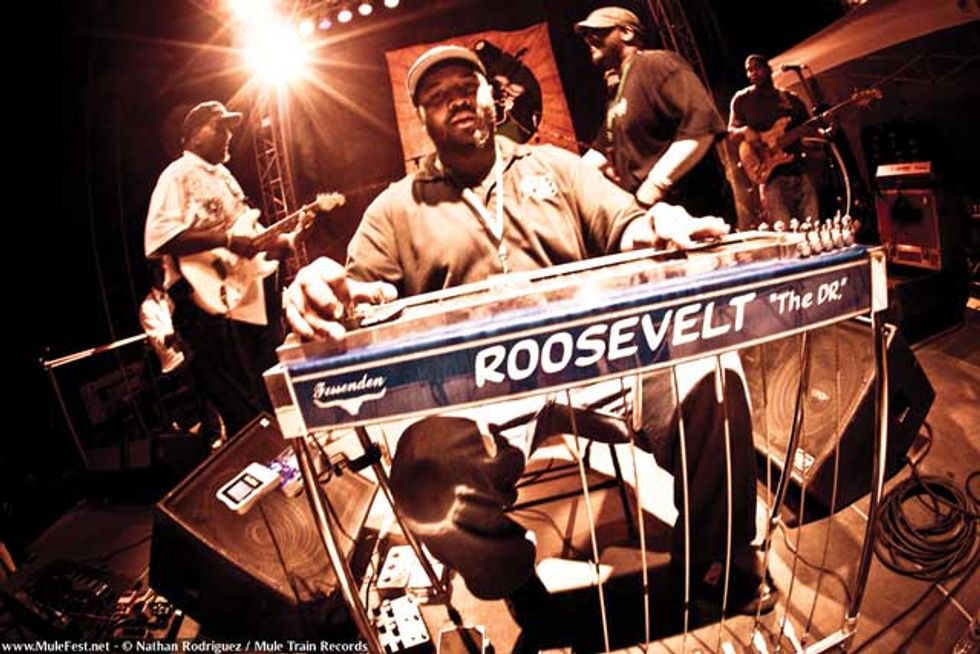

Lee Boys consists exclusively of family members: brothers Alvin (guitar), Derrick, and Keith Lee (vocals), and their nephews Alvin Cordy Jr. (bass), Earl Walker (drums), and Collier (pedal steel guitar). From about age 7, they all learned to play multiple instruments and grew up performing sacred-steel music at the House of God Church in Perrine, Florida. In 2000, they lost two family members who were significant musical influences—Reverend Robert E. Lee and Glenn Lee—and from that point, they decided to move beyond the walls of the church. “The torch was passed on,” Collier says. “That was my cue and signal that it’s time for me to take this to a whole ’nother level. Everybody felt the same way, and that’s when we went full-fledged onto the scene.”

In 2003, the Lee Boys had their first big tour playing the Blues to Bop Festival in France and Switzerland. “We were fresh on the scene, and we went overseas first. That was really big for us—I was nervous, nervous as dirt,” Collier recalls. “But the crowd went crazy. They were up dancing and praising.” By that time, other sacred-steel acts like Robert Randolph and the Campbell Brothers had already made their mark, but the Lee Boys hit the festival circuit with a vengeance and quickly developed a reputation for their frenetic shows. In 2008, after performing at Bonnaroo, the band debuted on national TV with a killer performance on Conan O’Brien. “That year was a turning point for us,” Alvin says.

Alvin Lee (left) and Roosevelt Collier (right) jam with Warren Haynes on his Man in Motion tour at Atlanta’s Tabernacle in 2011. Photo by Lisa Keel/peachtreeimages.com

Not surprisingly, the Lee Boys’ high-energy, improv-laden live shows have made them a favorite of the jam-band scene, too. In addition to trading licks with Sco, they’ve shared the stage with some of that genre’s brightest stars including Victor Wooten, Soulive’s Eric Krasno, and Warren Haynes. The latter, in particular, was instrumental in getting the band into the spotlight. “He let us jam on his sets with Gov’t Mule, gave us an opportunity to play with the Allman Brothers Band, and also let us open up for his band,” notes Alvin.

Haynes also signed the Lee Boys to Evil Teen, a label he co-owns, and made a guest appearance on Testify, the band’s latest release. Virtuoso guitarist Jimmy Herring was also enlisted to play on a few tracks and turned up the heat with his finger-twisting lines. “There’s a saying that if you want to be good, play with people that are better than you,” says Collier. “To play with Jimmy on the same tracks—that upped my game. Because of the stuff that Jimmy was laying down, I had to almost prove myself, you know? I had to play my heart out.” Collier is referring to tracks like “Always by My Side” and the title track “Testify,” which showcases an incendiary display of friendly fire, with Herring’s country-fied lines answered by Collier’s chromatically ascending patterns.

Roosevelt Collier's Gear

Guitars

DL [Dan Lawson] lap steel, Fessenden 10-string pedal steel

Amps

Fender Hot Rod Deluxe, Egnater Renegade 112, Marsh 50-watt closed-back amp

Effects

Pigtronix pedals (Overdrive, Envelope Filter, Sustain), Ernie Ball volume pedal, Dunlop Cry Baby Wah, Boss GT-8

Strings

Ernie Ball Steel Guitar Strings

“I was born with this gift of playing the steel, but it was up to me to take that gift and grow with it,” says Collier. “I used to go off a thousand miles a minute—on each song, each solo was a thousand miles a minute. I got the reputation for being fast, like, ‘Man, this guy is lightning speed.’ But when a friend like Rick Lollar would come onstage, he’d play like eight notes and eat me alive. The crowd would go crazy, because he built his stuff. It’s all about building. Save your big guns for later on.”

The songwriting on Testify comprises a unique mix of positive messages, catchy grooves, and sophisticated harmonies. Tracks like “Sinnerman” (which references Stevie Wonder’s “I Wish”) and “We Need to Hear from You” make use of unexpected modulations that would be equally at home on a Steely Dan cut. “Between jazz and funk, that’s where you’ll find me,” says Alvin. “If you listen to my chord progressions, you’ll hear a lot of jazz influences. A lot of the church musicians were big influences, but I also like guys like Victor Wooten, Stanley Clarke, and Jaco Pastorius—because I mainly played bass coming up. I also loved George Benson and Stanley Jordan.”

Alvin Lee's Gear

Guitars

Fender Strat with Roland MIDI pickup

Amps

Fender Twin Reverb, Roland JC-120

Effects

Roland GR-33 guitar synth, Boss GT-8

Strings and Picks

D’Addario .010 sets, Fender medium picks

The Lee Boys don’t come from an academically jazz background per se, but they‘re always experimenting, taking lessons, and applying their knowledge of theory to different styles. “I have a lot of jazz influence because of these guys I’ve come across,” Collier says. “This scene outside of the church has been a big influence on me. I’ve learned a lot. With us intertwining that theory with our traditional sacred steel—plus all the different genres that we listen to—I think that formed the Lee Boys style.”

Because the band members were raised as multi-instrumentalists, they often switch instruments onstage, with Alvin switching to bass or pedal steel and Collier playing electric guitar or bass. For the most part though, Alvin is on guitar—the perfect foil for Collier’s overdriven steel explorations. “My main guitar is a Fender Strat with a Roland MIDI setup and a GR-33 guitar synth,” Alvin says. “I use a MIDI piano or organ sound to give it a full, gospel-spirit feel. More or less, Roosevelt is doing all the picking and I stay in the background and kind of form the body with chords. From my background as a bass player, I use medium picks because I like to hit the strings a little harder. I usually do licks with my rhythm patterns, so I need some resistance, but I don’t use heavy picks because I don’t solo that much.” While Lee and Collier are both proponents of the Boss GT-8 multi-effects unit, it’s a family feud when it comes to amps: Alvin favors a Fender Twin Reverb and Roland JC-120, while Collier vehemently disagrees. “No, no, no, no, dude. I don’t use Twin Reverbs—I can’t stand them,” he says. “Back at church, the only amp that we actually played out of was a Peavey Session 500, which is a solid-state amp. But I learned about amps, wattage, and tubes. Now, I really don’t like to use anything past a 50-watt amp, because I like to crank the bad boy up. Now I use a Fender Hot Rod Deluxe, because it has a smooth overdrive channel. But my first-choice amp is an Egnater Renegade 112—that amp smokes. But a lot of your tone is your personal touch.”

YouTube It

Watch below for a taste of the Lee Boys’ high-energy, sacred-steel-meets-jam-band live performances.

The Lee Boys build to an insane climax

on “Come on Help Me Lift Him

Up” at the 2008 Bonnaroo festival.

Joined onstage by Warren

Haynes at the Fillmore Silver

Spring in Maryland, the Lee Boys

perform a rip-roaring rendition of

Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile.”

Bassist extraordinaire Victor Wooten

backs the Lees on this 2009

rendition of “Testify”—the title

track of their latest release—at the

House of Blues in New Orleans.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)