Steven Wilson likes creepy stuff—he must. There’s no other explanation for the Porcupine Tree frontman’s new solo album, The Raven That Refused to Sing (and Other Stories)—a prog-rock opus featuring six supernatural tales in the vein of M.R. James and Edgar Allan Poe, and eerie artwork by German illustrator Hajo Mueller. It certainly explains a lot of his other activities, including producing Opeth’s 2001 death-metal masterpiece Blackwater Park and collaborating with Opeth frontman Mikael Åkerfeldt on the decidedly macabre, Grammy-nominated Storm Corrosion project.

As with his compatriots in Porcupine Tree, Wilson seems to gravitate toward monster musicians, too. After touring with Aristocrats drummer Marco Minnemann and keyboardist Adam Holzman in support of his previous solo effort, 2011’s Grace for Drowning, Wilson also brought terrifyingly talented Aristocrats guitarist Guthrie Govan into the fold. Govan’s incredible legato technique and stunning phrasing lend The Raven a tastefully virtuosic guitar element that brings new dimensions to Wilson’s majestic vocabulary, and it was perhaps Govan’s presence in an already fire-breathing band that gave Wilson the courage to track the album almost completely live—a feat he never felt confident enough to attempt before. Of course, it helped that Wilson tapped one of the giants of studio engineering—Alan Parsons, renowned both for his work on Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon and his many hits with the Alan Parsons Project—to oversee the sessions at L.A.’s equally legendary East West Studios.

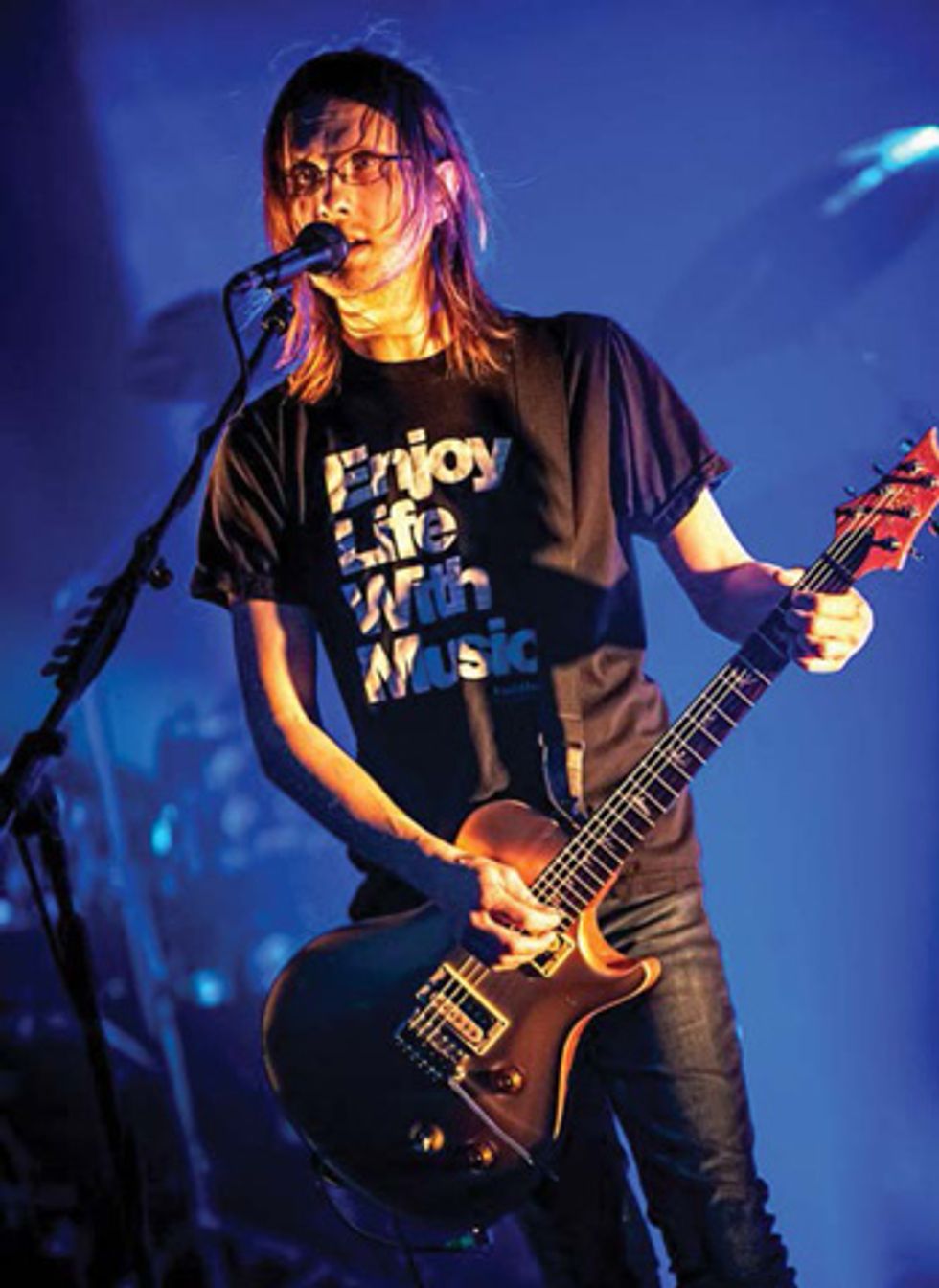

With a lush guitar tone courtesy of a PRS Custom 22 plugged into Vox AC30 and Marshall amps, Wilson pumps out chiming, expansive rhythm parts that form a locus around which Minnemann, Govan, and Holzman—as well as bassist Nick Beggs and flute, sax and clarinet player Theo Travis—rally their estimable talents on tracks that evoke classic Yes, King Crimson, U.K., Genesis, and even Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. “Luminol” features Steve Howe-inspired staccato licks and a massive, half-time Mellotron coda, while “Drive Home” has a lush shuffle buoyed by EBow’d guitars and a wriggling Govan solo, and the 3/4-time acoustic epic “The Watchmaker” boasts the album’s most memorable vocal and lyrical touches—and they’re possibly the heaviest, darkest harmonies Wilson has ever composed.

The Raven is the first time you’ve recorded a live band—what prompted that?

For me, that’s quite an unusual way to work.

I’ve simply never felt confident enough with

the whole team to do that. But with this band

and this engineer, I thought it was time to

try it—and it came out great. We recorded

the entire album live, in seven days, with the

exception of vocals and a few other things I

did later. There were seven songs originally,

but one didn’t make the final record. Every day

when we showed up, we’d pick a song and run

through it a few times while Alan would be

in the control room tweaking the sounds, and

then it was, “Okay, let’s go for a few takes.”

We’d do a few takes, then go into the control

room to listen back, pick our favorite one, add

some keyboard or guitar overdubs, and that

was it—finished. Next song, next day. I’m a

convert to that approach now. And the results

speak for themselves. In some of the solos, for

instance, you can really hear Marco responding

to the way Guthrie is phrasing, and those types

of moments become cumulative over a whole

record. They absolutely give the record a more

organic and warm feeling.

What was it like capturing such big,

pristine sounds with a legendary engineer

like Alan Parsons?

He did a fantastic job. It’s funny, but my

only concern with Alan was, “Will this

guy, who is really a producer, be okay with

taking on the engineer role again?” And he

was great—very happy to defer to me on

production. We had a great connection in

the studio.

So you weren’t interested in having him

act in more of a production role?

Alan had a number of good ideas in that

respect, and he is credited as associate producer

on the album, but I’m afraid I can

never be really produced. I’m too much of a

control person. No, I couldn’t do it—but I

do understand the philosophy. It’s interesting

to put yourself in the hands of someone

who perhaps doesn’t have the same ideas

that you do, but I just don’t know if I could

do that. If I’ve written songs, I know how

I want them to be born, y’know what I

mean? But having someone come in with

cool ideas about how to record things?

That’s fabulous—that’s just what I wanted.

“Let’s try this mic” or “Let’s try putting that

instrument through a Leslie cabinet” … great! But the sort of producer mentality of

“Can we shorn this bit?” or “Can we make

this bit longer?”—no, that’s not for me.

Forget it, mate!

Steven Wilson performs with his solo band in Belgium on March 12, 2013. Photo by Tom Van Ghent

Tell us about bringing Guthrie

Govan aboard.

I didn’t know about the Aristocrats when

Marco came onboard and, admittedly,

that kind of fusion music is not my thing.

But I went to see them play and, watching

Guthrie, I just thought, “This guy could do

some amazing things for my music.” I knew

he could help me take my music to a much

higher level. Of course, the worry with guys

at that level is whether there’s enough to

keep them interested. I mean, I don’t like

shredding and I don’t like fast playing just

for the sake of it. I like guys who will play

one note that will break your heart, if that’s

the right thing to do. So the first thing

was to figure out if Guthrie was going to

be okay with that. And he absolutely was.

He’s a truly great musician—not because

he’s technically phenomenal—but because,

despite that, he always understands how to

play what is right for the song. There are

things on the record—like the title track, for instance—where he

only plays three notes. He

did exactly what I’d hoped

he would do, which is to

take the whole record to

another level.

In addition to blazing

solos, he plays quite a few

nice, melodic lines with a

lot of warm, jazzy tones.

Yes, we did a lot with that

“jazzy” guitar tone. We call

it the “Lonely Swede Lost

in the Forest” sound—a sort

of jazzy, warm, and dark

clean sound that’s mixed

with a mono plate reverb.

I love that sound—it’s on

many ’70s records, and it’s

especially noticeable on old

Scandinavian records. My

buddy Mikael Åkerfeldt

from Opeth uses that sound

quite a lot. The use of mono

plate reverb, in particular,

came from working on the

old King Crimson records

that I remixed. I learned from

working with Robert Fripp that a lot of the

time they kept the reverbs mono, and they

kept the reverb returns with the instrument. If

the flute was on the right, that’s exactly where

the reverb was, too. They didn’t do that very

’80s thing, where you take a guitar, keyboard,

or drum sound and put it through a massive

stereo reverb—wide-screen cinema!—and suddenly

you’ve lost all this space in your mix and

you wonder why there’s no space for anything

else. That mono reverb has a wonderful character

about it, an aura—almost a halo around

the sound.

You write such great chord changes—they’re often for rock songs—and Guthrie

is such a master of outlining chords using

chord tones and modal playing.

That’s something I really notice from old

records, ’70s records—musical phrases and

sections repeat, but they don’t completely

repeat, if you know what I mean. It’s one of

the malaises of modern music that sections

of songs and musical moments literally

repeat verbatim—like someone’s gone and

copied and pasted them. If you listen to

records from the ’70s, sure, they’re playing

riffs, but usually the guitarist is constantly

noodling around those riffs,

adding little colors, little textures. And it’s

something that comes, again, from the idea

of a band, in the studio, rehearsing and

writing together—playing live together in

the studio. So, in a way, the music is always

in a state of flux. Because of computer technology

and the way we tend to record in a

very piecemeal way these days, we tend to

edit the [expletive] out of things so that all

of those happy accidents where the guitar

player is noodling in the background just

behind the vocal—which is a lot of what

Guthrie was doing—are lost. I don’t hear

that on many modern records. In fact, I

don’t hear it on any modern records.

Guthrie Govan on Soaring with The Raven

Steven Wilson is still incredulous. “I mean, we’d gotten this LaRose Classic Jazz [Jazzmaster-style] guitar with a Sustainiac sustainer circuit in the studio on the second day, and I asked Guthrie what he thought of it,” Wilson recounts. “He picked the thing up and, literally, the first thing he played was the solo on ‘Drive Home’—the solo that made the album. First time, first take. Isn’t that insane?”

Photo by Tom Van Ghent

Even crazier is that, during the solo—which Govan tracked live with the band—you can hear the E-string popping out of the saddle, forcing Govan to play the rest of the solo without it. “I later learned,” the Aristocrats chopsmaster explains, “that the Jazzmaster bridge/tailpiece design is famously ill-equipped to deal with extravagant string bending!” While Govan thought later versions of the solo sounded “a little more perfect,” the other players unanimously preferred the first take. “I suppose the first one did have a certain vibe to it,” he shrugs, “presumably because I was still getting used to an utterly unfamiliar instrument, which made me play a little differently. And, having played a lot with Marco in the Aristocrats, I think we had a couple of spontaneous interactive moments during that solo which could have only happened in real time.”

As far as his approach to Wilson’s Raven sessions on the whole, Govan says, “Steven described the overall guitar vibe he wanted for this album, and I just tried to serve the music as best I could, whilst remaining true to myself—but without making any effort to leave a giant GG thumbprint all over the record.” Govan called on a small coterie of pedals, including a Suhr Koko Boost, a Z.Vex Mastotron Fuzz, a DLS RotoSIM, and a TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb, and he typically recorded time-domain effects live, per Wilson’s request. While darker textures and clean-toned lines do make up a significant portion of Govan’s contribution, there are plenty of scorching, dramatic solos, too.

“I did try not to go too over the top with the frantic technical stuff, but a couple of ‘sheets of sound’ moments probably slipped through the net anyhow,” he laughs. “I’ve gathered that there are some folks in the progressive rock community who get turned off when a guitar player exceeds their chosen notes-per-second quota. But as I remember once observing to Steven, these are often the same people who would be perfectly happy to hear a sax player playing at a comparable velocity. So I try not to worry too much about those people!”

Presumably, you demoed all this material

in Logic Pro beforehand, like you

have on past projects. That must be quite

a challenge, demoing 11-minute songs,

each with several sections, as well as

tempo and time-signature changes. The

drum parts alone …

Yes, but that’s exactly why they really have

to be demoed in full. But, yeah, I spend

a lot of time working on the song structures.

I use the EXS24 sampler in Logic to program the drums—I play the basic

drumbeat ideas on a keyboard controller—and then I send that to Marco. From

those demos, he learns the structures and

basic rhythms, and then throws it all away

and plays it like only Marco can. The thing

is, with this kind of music, you cannot

divorce what the drums are doing from the

songs—they’re integral parts of what makes

the song what it is. If you’re a Neil Young

or Bob Dylan sort of songwriter, your song

is basically you and the guitar or piano. You

don’t have to think too hard about what

the drums are going to do—it’s fairly obvious.

But with this type of music, the drums

may be the lead instrument, in a sense: They may be the basis for a phrase, a whole

part, or even the entire tune. So you have

to really think about that, and you have to

write that into the composition.

The same is true of the other instruments. A lot of the music was written on the bass guitar, too. For example, the way the album starts, with “Luminol.” You can clearly hear that the bass figure is the foundation of that part of the song, so of course I had to demo it on the bass guitar. Basically, when I’m in the studio demoing these songs, I’ve got guitars and basses and keyboards and drum modules around me, and I’m essentially doing my less-than-spectacular versions of what I want the guys to eventually play. It’s not just about sketching each part, but about showing the guys how it all works together—how the whole musical story unfolds. And they are musical stories, not just in the sense of the way I use the ghost stories around them—that’s another thing entirely—but also the way all the different sections unfold.

In a way, while progressive rock gives me all this freedom to throw traditional pop song structures out the window, it’s also a bit of a mind [expletive], because I have all these different sections to deal with and no set way to arrange them. In fact, I can easily write all the different sections of one of these multi-section songs in a single day, but I can then spend an entire week juggling them all around before I arrive at the right order. That’s when I know I’ve found the key to a track, especially some of these longer pieces. This also means I have to fly things around in Logic and tweak tempos to make sure the parts fit together well before I take it to the players. Because you may decide one section makes sense following another section, but then the tempo may seem sluggish in comparison and you need to bump it up two or three beats per minute, and then it’ll feel just a little more right than it did before.

Which guitars, amps, and effects did you

favor for this album?

I used the same PRS Custom 22 that I’ve

used for a long time. I’m now endorsed by

PRS, but the very first PRS I bought when

I was very young is still my favorite one. I

have to confess I don’t know a great deal

about guitars—people ask me what guitar

I play, and I say “a red one.” I also used

a Stratocaster a bit on “The Raven That

Refused to Sing.” In terms of pedals, I used

a bunch of the new TC Electronic TonePrint

pedals, including the delay, the reverb, and

the vibrato. I love very subtle modulation on

guitar tones. I don’t like choruses, flangers,

or phasers, but I do love a little vibrato or

tremolo, or sometimes a bit of Leslie—we

put one of Guthrie’s solos through the Leslie

on “The Pin Drop.” Tremolo, vibrato, and

rotary speaker give color to guitar sounds

that might otherwise be sort of flat. My

amps for the sessions were a Vox AC30 and a

pair of old Marshall 100-watt heads.

There’s a lot of great acoustic playing and

very lush, distinctive acoustic tones on

the album.

Most of the acoustic on this record is

an Ovation in Nashville tuning, which is basically all the higher strings of a

12-string guitar. It has that wonderful

crystalline quality—I find it incredibly

inspiring. And adding a capo to

the second fret gives it even more of a

mandolin-like register. I didn’t know

much about Nashville tuning until

about a year ago. We were on tour and

a fan brought me an Ovation guitar as

a gift. It was so nice that I said I simply

couldn’t accept such a generous gift,

and I had little use for another acoustic

guitar anyway. Well, Tonto, my guitar

tech, said it’s a lovely gift, why don’t you

accept it and I’ll string it up for you in

Nashville tuning? I said, what is that?

Well, immediately upon playing it, I

knew it was going to inspire something.

I ended up writing “The Watchmaker”

and “Drive Home” on it.

Steven Wilson's Gear

Guitars

PRS Custom 22, AlumiSonic Ultra 1100, Visionary Instruments Video Guitar, Babicz Dreadnought Cutaway, Ovation acoustic (Nashville tuning), PRS SE Mike Mushok signature baritone, Fender Stratocaster

Amps

Vox AC30, Bad Cat Lynx 50 head driving a Bad Cat 4x12 with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

TC Electronic Flashback Delay/Looper, TC Hall of Fame Reverb, TC Shaker Vibrato, Dunlop Cry Baby wah, Boss FV-500L Stereo Volume Pedals, TC Electronic G-System, Boss SD-2 Dual Overdrive, Source Audio Soundblox Multiwave Distortion,

Carl Martin Compressor/Limiter, Option 5 Destination Rotation Single, Boss GE-7 Equalizer, TheGigRig MIDI-8 foot controller

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

D’Addario EXL110 sets (electric), D’Addario EJ10 sets (acoustic), D’Addario EJ38H sets (Nashville-tuned acoustics), D’Addario EXL140 sets (detuned electrics), Jim Dunlop Tortex 1 mm picks, Providence E205 guitar and P203 patch cables

I tend to double-track the Nashville parts with an electric guitar, which warms it up and gives it a bit more body. That’s pretty much the big rhythm sound you hear on “The Watchmaker” and “Drive Home.” Interestingly, though, apart from that I have actually taken to not double-tracking stuff on this album, with one or two exceptions. The exceptions would be the acoustic guitars, which I tend to double or even quadruple track.

Why?

Another thing I noticed about the classic

’70s albums I was remixing is the economy

of overdubbing. Double-tracking

tends to sound impressive in the studio,

but it also takes away from some of the

character of the performance as it irons

out the quirks that give a part so much of

its personality.

Do you have any tips for recording—perhaps how to best capture a solo or favorite plug-ins for guitars or mixing? My favorite plug-ins for mixing are the Universal Audio ones, especially the EMT 140 plate reverb, the 1176 compressor, and the SSL channel strip. The native Logic EQ is also great for the basics. But I have to say that, generally speaking, the guitars are untreated once they’re recorded—perhaps just a little EQ to filter out low end or add a little more air at the top end, but that’s all. I can’t think of any particular approach for getting a solo to sit right—but sometimes a really nasty EQ, or heavy compression, or just making it very loud.

YouTube It

Watch a live performance of music from The Raven, as well as

some intimate behind the scenes footage from the studio sessions.

The 2012 Raven band—featuring guitarist Niko

Tsonev—performs “Luminol”

live in Mexico City.

Steven Wilson and his lineup

of monster players hash out

some of the arrangements

while working on “Luminol”

at East West Studios in L.A.

Tracking “The Watchmaker”

with Alan Parsons at the

console. Govan’s beautifully

fluid solo overdub begins

at 1:45.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)