Victor Wooten just might be the busiest bass player in the world (and no, we’re not talking about his note-per-measure ratio). His days are packed with clinics, radio appearances, meet-and-greets, and soundchecks, and night after night, the man and his righteous band take it to the max, proving that he never, ever lacks for ideas, and can boldly surpass artificial limitations and the expectations of bass fanatics everywhere with marathon performances that border on the superhuman. The next morning might find the father of four tending to his family, his label, his music camps, and his other gigs, or the follow up to his acclaimed book, The Music Lesson, as he heads to the next town. And what does he do when he has a little time off?

He practices. “I’m trying to improve every side of my playing, but right now I’m working on getting more proficient at being able to solo through jazz changes,” Wooten says. “I’m okay at soloing through the changes once I hear them, but I’m not as good at just looking at a piece of sheet music and knowing what to play. That’s a fun lesson, though.”

The five-time Grammy winner, whose name is synonymous with electric bass virtuosity, will never stop evolving. Like Michael Jordan shooting free throws in the early hours before games, 48-year-old Wooten isn’t in it for the money, the notoriety, or the endorsements. It isn’t work, it’s love, and it’s about striving toward his highest potential, knowing all the while he’ll never reach it. And therein lies the greatest game for the man who will go down in history among players who are exactly that: the greatest of the greats.

So it makes sense that Wooten has raised the bar and simultaneously released two new albums on his own label, Vix Records. Words and Tones showcases Wooten’s collaborations with some of his favorite singers, including Saundra Williams, Divinity Roxx, and Meshell Ndegeocello, while Sword and Stone flaunts instrumental, orchestrated takes on 11 of the same songs, with different solos, string arrangements, and horn sections (plus three other tracks). Both albums showcase Wooten’s unique combination of R&B, contemporary jazz, funk, gospel, and world music while maintaining his signature, bass-tastic approach. As you might expect, there are plenty of virtuosic licks and jaw-dropping techniques, but Wooten’s primary focus is on grooving.

His tireless work ethic could make anyone feel lazy, but that’s far from his intention. In fact, the man who dedicates a large chunk of his time to sharing his knowledge with others understands that when people deem him the best, they are merely seeing the best in themselves. Perhaps this Zen outlook comes from all the effort Wooten puts into his craft, or it could be a manifestation of the wide-eyed joy that has stayed with him since he first picked up the bass at age 2. Whatever its source, the force of his creativity keeps Wooten’s past achievements in the rearview mirror, his soul and his craft steadily moving forward into the unknown.

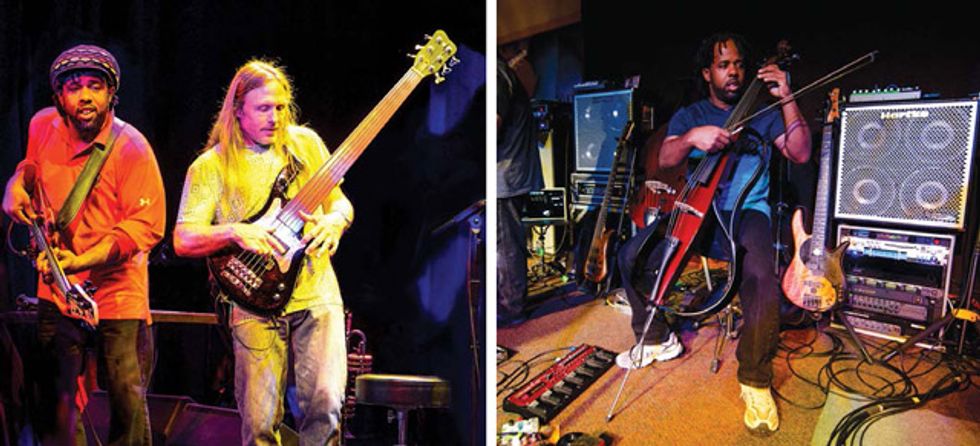

LEFT: Two bassists are better than one, that’s why Wooten tours with 6-string

fretless wonder Steve Bailey.

RIGHT: Wooten onstage with a Yamaha SVC-110SK SILENT Cello.

Photos by Steven Parke

What inspired you to release

instrumental and vocal

albums at the same time?

I’ve wanted to put out two

albums at once for a long time.

Many years ago, when I was

on two different record labels,

I wanted to put out a record

on each label on the same day,

which I thought would be so

cool. But record companies

don’t like to work together like

that because they’re competitors.

This time around, I had

planned on doing just one CD

with female vocalists. In most

cases, I allow the vocalists I

work with to write a majority

of the lyrics so that they’re singing

what’s true to them, and so

they get credited as writers. But

as I was putting melodies on

the songs so the singers could

get a feel for them, I realized

I liked these songs as instrumentals,

too. Then it hit me

that I could release these as two

separate records—now that I

own my own record label, I can

do whatever I want with my

albums. I finally had an opportunity

to pursue an idea I’ve

had for a long time.

How did you decide which

songs to put on these records?

A lot of it just comes out on its

own. I’m not the type of musician

who’s writing and recording

all the time. I do have songs

I’ve recorded in the past and

have not used. In a couple of

cases, I put old songs on these

records. I have a voice recorder

on my phone, and whenever an

idea pops into my head, I either

sing it or play it into my phone.

So I went through those ideas,

wrote charts from them, and

wrote songs based on them.

How did you record

these albums?

I used all Pro Tools. I used

a little bit of both DI and

mic’ing my cabinet, but mainly

DI. I always keep a cabinet set

up in the studio so I can do

both and mix the two, but this

time I didn’t use my cabinet

much in the mix.

Did you try any new techniques

on these albums?

I’m always looking for new

tricks and techniques. I always

use a ponytail holder hair band

on the neck of my bass, and I

found that if I moved it to the

17th or 18th fret, I could make

sounds like a guitar player using

pinched harmonics. So I put

distortion on the instrument

and, just like a guitarist, I took

a solo on Sword and Stone that

sounded just like a guitarist

would. It was definitely something

new for me.

You’ve used that hair band on

your bass for many years now.

What function does it serve?

It serves as a string mute, and

depending on what you’re playing,

it’s great for muting the

open strings. Between myself

and my brother Regi and his

students, we’ve all come up

with different ways of using the

hair tie.

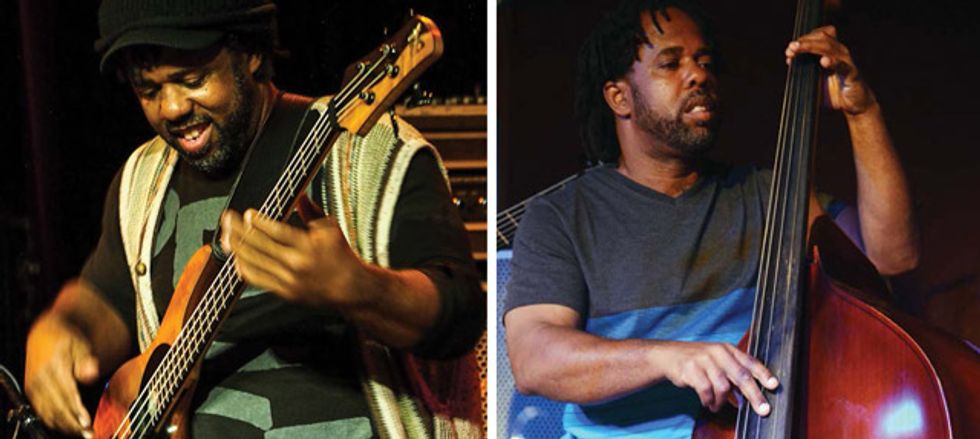

LEFT: Hands a blur, Wooten flits his mitts across the fretboard of his signature

Fodera Monarch at a November 9, 2012, gig at the State Theatre in Falls

Church, Virginia. RIGHT: Wooten plays an upright bass during a show last summer at Rams Head

Live in Baltimore, Maryland. Photos by Steven Parke

What have you been working

on recently?

Being able to play more melodically,

and playing more lines.

I’ve always been a rhythmic

player and I’m very comfortable

with that, but I want to play

lines like a great piano player or

horn player. Right now I’m on

tour with the Jimmy Herring

Band, and seeing Jimmy play so

well and so cleanly makes me

strive to reach that level.

How do you go from being a

bandleader to a sideman?

In either situation, I’m listening

to the groove and playing

what the song is asking for. It’s

just like us talking right now:

Everything I’m going to say is

based on what you say first.

It’s mainly about listening—I

try to do more listening than

talking. That’s the essence of

groove. If I’m really listening to

the song, then I’ll know exactly

what to play.

How has your playing evolved

over the years?

I think that the instrument

has taken a backseat. It’s not

about your instrument—it’s

about what you have to say.

Your instrument happens to

be the one you use—it might

be a bass, voice, an alto or

soprano—but who cares? It’s all

about what you’re saying with it.

Right now, you’re not thinking

about how your lips are moving

or the physics of your talking,

you’re just speaking. That’s

how I approach the bass—by

approaching the music instead.

How did you start playing bass

when you were two years old?

Actually, my brothers had me

play music with them before I

began playing bass. They would

have me sit in the room with

them and have me strum a toy,

keep time, and start and end at

the same time as the song. When

I was 2, Regi took two strings off

his extra guitar and it became a

bass for me. That’s when I really

started learning how to play the

notes to songs I already knew.

So your family has shaped

who you are as a musician?

Totally. That was my upbringing.

I played with my brothers

for the first half of my life, and

they truly turned me into who I

am. Just like kids who grow up

with a good family and go off

into the world to do their own

thing, their upbringing always

stays with them. And musically,

my background all began with

my family.

What was your first bass?

It was a copy of a Paul

McCartney Hofner violin bass,

but it was made by Univox. I still

have it. After that, I was playing

an Alembic Series 1, which is a

huge instrument that’s also really

heavy. I was so young and short

and small, and it was huge.

What has kept you playing

Fodera basses for all these years?

I got my first Fodera in about

1983. Back then, it was just a

$900 bass Vinny Fodera and

Joey Lauricella had started

making that year, and we

just happened to have met

up at the right time. I got it

right out of high school and

it felt just amazing. It fit me

perfectly. I’ve stuck with them

ever since.

What do you look for in a bass?

The first thing is that it has

to feel good. I’ve done very

little to my Fodera basses. The

only thing I’ve had Vinny and

Joey do for me is move the

volume knobs and the switches

as far back near the bridge

as possible so that they don’t

get in the way of my right-hand

strumming technique.

Although I’ve changed how my

particular instrument looks—

with a yin-yang symbol, for

example—the bass I use today

is pretty much exactly the

same as that Fodera Monarch

bass I got 30 years ago.

What inspired you to switch

to Hartke amps?

I was just ready for a change

after many years of using great

Ampeg gear, so I took some

time to just look around and

see what was out there. I spent

a year on tour with 25 different

bass cabinets and my

crew would set up a different

rig each night. So I got to

really hear, play, and experience

many different amps. It always

starts from sound, so I got the

amps with the best sound to

me, and then I started reaching

out to the companies, because

who the people in the companies

are is very important to

me. If I’m going to endorse

a product and put my name

behind it, I’m really endorsing

the people who work at those

companies. It’s like a marriage.

You’re not just going to

marry someone because they’re

beautiful, you gotta know who

they are. There were companies

whose amps I chose not to

use because of the people. But

I needed a company to support

me wherever I went, and

Hartke took the cake easily. I

got one of the first HyDrives

that they ever made.

And how is the new Hartke

HyDrive series?

I love it. It’s powerful, so I never

have to turn my volume up too

high. It’s a really bright cabinet,

so you have to be prepared for

that, but with my 1x15 cabinet,

I get all the bottom I need.

How important is your gear to

your sound?

I want gear that’s so transparent

I forget it’s there. I do clinics

for Hartke all over the world,

and sometimes I forget to talk

about them. And when I do, I

tell people that me forgetting

about the gear is a wonderful

thing, although for Hartke, it’s

not so good (laughs). I’m much

more musical and I always get

it more right in my heart and

in my head, but by the time it

comes out, there’s a bunch of

mistakes in it, and it doesn’t

sound like it did in my brain.

When the amplification is

projecting exactly what’s in my

head, then I forget it’s there.

Really, that’s the biggest thing

I’m looking for. That’s why I

have a hard time sitting in a

room and testing an amp. I’m

thinking about it too much. I

need to put it in real context.

What have you been listening

to lately?

One thing that might surprise

people is that when I’m driving

in my car by myself I’m usually

listening to country music.

I got into it when I worked

at Busch Gardens amusement

park in Virginia and learned

about country and bluegrass.

Listening to it in the car gives

me a chance to practice my

music theory. Because the chord

changes move by slowly, I can

call them out and say, “That’s

a I chord, that’s a VIm, there’s

a IIm chord, there’s a V7.” I’ve

also started to predict where it’s

going to go so I can see if I’m

right, and I can tell what’s going

to go on before it happens.

Who are your greatest

bass influences?

It all starts and ends with my

brother Regi. But Stanley Clarke

is a big one, Bootsy Collins,

Larry Graham, Jaco Pastorius,

of course, and there are tons

of other people like Chuck

Rainey, Louis Johnson, James

Jamerson and Willie Weeks.

Acoustic players like Ron Carter,

Charles Mingus, Scott LaFaro.

And that’s just bass players. My

musical influences span a lot of

different instruments.

How does the bass resonate

with your personality?

It’s a supporting instrument.

It’s designed to make other

people feel and sound good. It

seems like a lot of the time, we

forget that. That instrument

was not designed to be on top,

and it’s rare that you’ll find a

bass player who is leading a

band. It’s designed so that most

of the time we’re going to be

sidemen. But I find that when

most of us bassists are alone

practicing, that rarely comes

into the picture of what we’re

working on. We’re going to get

hired based on our ability to

be a supporter, but when we

practice, we learn new scales

and work on our licks and our

solos and how to play faster.

But you never get hired for any

of that. You have to honor the

true spirit of the instrument.

How does it make you feel

when people tell you you’re

the best ever?

I understand that what people

think, good or bad, is up to

them and not me. A little kid

who looks up to his big brother

for being able to dunk a basketball,

for example, is really

seeing his own future potential.

It wouldn’t make sense for the

older brother to stop dunking

the ball because the younger

brother can’t, so he keeps doing

it. When people put me up

on a pedestal, I used to take

myself off it and tell them I

wasn’t that good, or I’d shrug it

off. But what I realized is that

whether they know it or not,

when they think they’re talking

about me, they’re really talking

about themselves. I don’t want

to diminish their dreams by saying

I’m not that good. Instead,

I accept it, say thank you, and

then we move on.

What would you ideally want someone to say about your music after hearing it for the first time? That they really enjoyed it and that it inspired them to go do it. I want people to feel something. I want them to think less about the technique and the playing behind it and feel the big picture of it all. Music should hit you in your heart and make you feel something real, just like an Otis Redding song does.

What inspires you to keep

growing as a player?

You have to understand that

music never ends and there’s

always someplace new to go

with it. A good friend of mine

once said that it’s like trying to

count to infinity—no matter

how far you go, you’re no closer

to the end. In no way do I

think that I’ve reached the limit

or the full potential of my playing

ability. None of us have.

Victor Wooten's Gear

Basses

Fodera 4-string fretted Monarch

basses, various upright models

Amps

Hartke HyDrive LH Series, Hartke

HyDrive 410, HyDrive 115

Effects

Rodenberg Distortion pedal,

Boss GT-6B Multi-effects pedal,

Zoom B3 Multi-effects

Strings

D’Addario nickels strings

(.040, .055, .075, .095)

YouTube It

Here Wooten demonstrates the harmonic technique

heard on his new track “Sword and Stone,” where

he uses a hair tie on the fretboard of his bass:

This clip from a clinic in Mechanicsville, Virginia,

demonstrates Wooten’s tremendous grasp of

melody, harmony, and rhythm:

In this clip from the 2010 NAMM show, Wooten

plays his famous version of “Amazing Grace,” an

arrangement he first unveiled with the Béla Fleck

and the Flecktones:

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.