|  |  |

Click here to see a photo gallery of Iron Maiden's 2010 touring gear. |

In their 35-plus years as perhaps the greatest metal band of all time, Iron Maiden has sold more than 100 million records worldwide. They led the New Wave of British Heavy Metal movement of the late 1970s and early 1980s, and they forever changed the sound of heavy metal. Directly or indirectly, Maiden’s influence permeates the sound of countless bands from yesteryear and today—including hot-shot young bands like Avenged Sevenfold, Dragonforce, and Trivium. In fact, it’s fair to say that classic Maiden albums like The Number of the Beast, Piece of Mind, and Powerslave are essential listening for any true headbanger.

Like their iconic, zombified mascot, Maiden shows no signs of faltering— even in the midst of an economic crisis and the changing face of the music industry. The band’s latest release and 15th studio album, The Final Frontier, debuted at #1 in 28 countries and at #4 on the Billboard 200 chart in the US, making it their highest-charting US release ever. The album—which is also the band’s longest to date at 76 minutes and 34 seconds—features the expected epic compositions imbued with some unusually challenging prog-inflected escapades.

Premier Guitar recently caught up with Maiden guitarists Dave Murray, Adrian Smith, and Janick Gers to get the inside scoop on The Final Frontier. About an hour before doors opened at their sold-out show at PNC Bank Arts Center in Holmdel, New Jersey, we sat down for the interview at a hotel 40 miles away in midtown Manhattan. The band was pretty wrapped up in the final game of the World Cup, but Murray, Smith, and Gers soon got around to amiably discussing the new album and divulging secrets of the Maiden sound before making the trek back to the venue.

What was the songwriting process for this album?

Murray: It was pretty much the same as always. Everyone would bring in ideas, which eventually went to Steve, who is like the nucleus of the band. He’d take the parts and get the songs into shape. He also wrote a lot of the lyrics on this album.

Smith: Because Steve’s a bass player, he thinks a little bit differently. He gets you to play things you normally wouldn’t play and sometimes it can be a bit uncomfortable. “El Dorado” was Steve’s song, and he had everything written down to the last detail from start to finish. With Steve’s stuff, you have to play it exactly the way he hears it and that can be very rigorous. Janick volunteered to do the parts. Steve showed him what to play, and it took Janick a lot of work to do it the way Steve wanted him to.

That’s how it used to be in the old days when Steve would write a lot of songs. We’d sit down and go through it the way Steve wanted it, even so far as the picking accents, using downstrokes or upstrokes.

Gers: There’s no set way of doing it, and that keeps it fresh. I think if you get into the rut of doing it the same way every time, you lose the spontaneity. You never quite know what’s going to work and what isn’t. I’ve brought in stuff that I thought was amazing and it didn’t get on the album.

Classic Maiden albums like Piece of Mind, Powerslave, and Somewhere in Time were recorded at Compass Point Studios. More than two decades later, you returned there to record The Final Frontier.

Murray: Compass Point hasn’t changed much in 25 years, although [producer] Kevin Shirley brought in all of this new equipment to keep the album sounding current. We embrace new technology. It doesn’t change the sound or the identity of the band—it just makes the whole process more spontaneous and keeps everything fresh. We like to get an analog feel, but we used Pro Tools on this album—like we have on the last few albums—to speed things up. You can record really quickly on it and jump sections around. We had a two-and-a-half-month window to record, but we finished recording in six weeks and Kevin took the tracks to California and did the final mixing.

Yet you still incorporate such old-school methods as recording without a click track.

Murray: Music has to live and breathe and move around. If you put a click track to any Iron Maiden song, it’s going to be moving around. The thing is that it moves in the right places so it adds dynamics. It might lift up a little bit in the chorus or the solos, but I think if you listen to the great rock bands from the ’70s, you’ll hear the same thing. Everything’s moving around, but it’s like a pulse.

Gers: Yeah, isn’t that what music should do? It’s supposed to breathe. You listen to the Beatles, Zeppelin, and Hendrix, and doesn’t everything fluctuate? It’s supposed to come from here [points to his heart]. That’s where all the greats come from. The Berklee guys that play the same riff for 12 hours—that comes from the head. I’m talking about feeling— about guys like Paul Kossoff or Tommy Bolin. It’s a technological age we live in now, and producers are always trying to bring in their own ideas to make things more “solid.” But music should move—it’s organic and it grows.

Smith: We don’t overly concern ourselves that every beat has to be perfect, as long as it feels right.

Dave Murray during the Somewhere on Tour tour at Joe Louis Arena in Detroit,

Michigan, May 18, 1987. Murray is playing his trusty black Fender Strat,

which appears to be outfitted with a Kahler tremolo. Photo by Ken Settle

Does one of you ever go in a different direction, tempo-wise, than the rest of the band?

Murray: Sometimes one of us might get excited and start moving, and the band might follow that. It’s kind of a natural thing, because of the adrenaline or the way the audience is reacting to the song.

How would you address that in the studio?

Murray: Well, with Pro Tools you can move stuff back into time, if need be [laughs]. Obviously, the timing is an important factor, but what’s more important is how it feels.

Are your solos worked out or off the cuff?

Murray: On this album, they were basically all spontaneous, although there may have been a few melodies I had worked out in advance for some songs.

Gers: Same here. It’s spontaneous, but if I have a melody I like, I’ll use it. Even live, there are certain things you keep the melodies for. I find it impossible to play the same thing twice. And if you’re playing how you feel, how can you play the same thing twice?

What makes a good solo?

Smith: A little bit of melody, a little bit of flash. And it should be something memorable. There’s a song on the new album called “Isle of Avalon” that has more of a fusion-y kind of solo. It’s over an unusual time signature—7/8. That was nice, because it makes you play something different. You can get into the trap of playing the same old thing over and over again. I was happy with that one.

Gers: It has to be something that enhances the song. It’s not about me doing a solo—not about, “Now it’s my chance to shine.” It’s about making the band sound better.

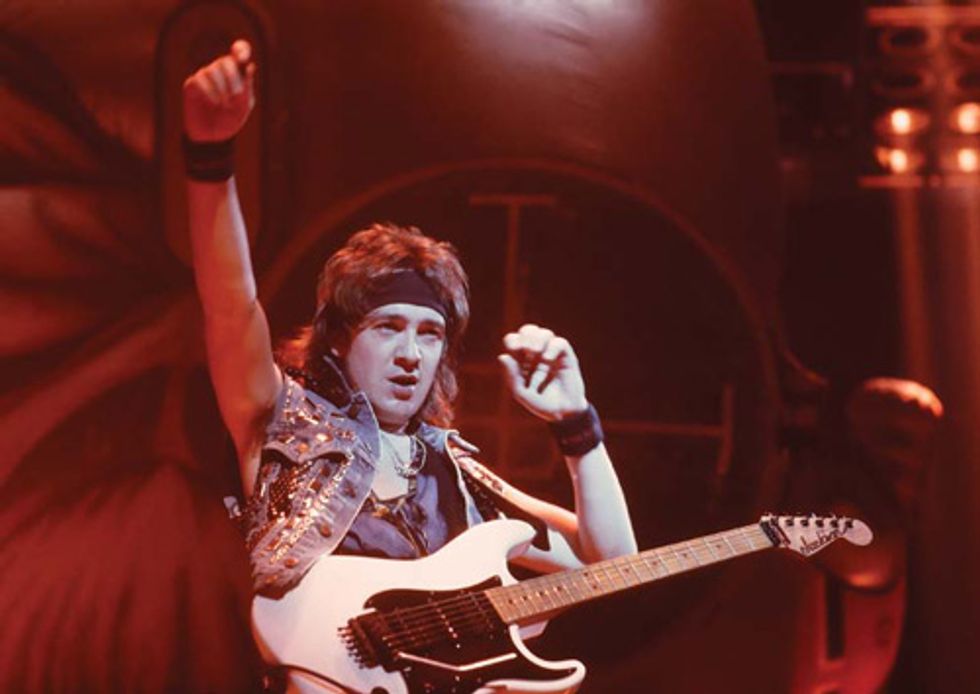

Adrian Smith rocks his Floyd Rose-equipped Jackson on the World Slavery tour, June 12, 1985,

at Pine Knob Music Theatre in Clarkston, Michigan. Photo by Ken Settle

With three guitarists, how do you get the subtle nuances of harmonized bends and vibrato to sound cohesive?

Murray: We sit down and listen to each other, and you hear what someone is doing and naturally go there. It’s not hit or miss. Obviously, if anything is bent totally out of key, we’ll just go back and redo it.

Gers: If I need to match them, I’ll match them, but more often than not we don’t plan out these things. The whole point is that you have three very different guitarists. I mean, if we both sound exactly the same, why don’t we just track Adrian? Music is personal. I’ll play how I play. Smith: It can be very difficult with three guitarists, though. I’m really sensitive to tuning, intonation, and bending right together. I notice that a lot of people don’t hear it, but I hear it and it really bothers me. Kevin doesn’t hear it, and Steve doesn’t hear it. Sometimes I have to fight to say, “That does not sound right.”

So you will redo a track to, say, match the rate of a vibrato?

Smith: Yeah. Dave and Janick probably have similar vibratos—a quicker vibrato—and I have a slower vibrato. Sometimes, if it’s for the good of the song, I won’t do a vibrato. I’ll just play it straight and it fits in with their vibratos. I’ll compromise. Performing live is easy, but recording three guitarists is very difficult.

Gers: However, you can take it to the extreme and get us to play it exactly the same, and put the bends in exactly the same place. But then you might as well have just one guitarist do all the tracks. If you listen to [Deep Purple’s] Fireball, you’ll hear two voices and one might be slightly off kilter. Ian Gillan did this a lot in the old days of Deep Purple. I love that. If you listen to the early Sabbath solos, Tony [Iommi] would play two solos and one would be doing a completely different thing than the other. I love that!

Adrian, I know you sometimes tune down to D or lower, but Janick and Dave don’t. Was that the case on this album?

Smith: I actually pleaded with the other guys to tune down for one song, “Mother of Mercy,” because they don’t really like doing it. The original demo was in E, but it was too high for Bruce to sing so we moved it down to D—which isn’t really a heavy key. I played with Bruce’s solo band, and he was really into the dropped-D tuning. Steve didn’t tune down though.

Since you use Floyd Roses, do you have a separate guitar for the dropped-D tuning?

Smith: Yeah. You have to.

What piece of gear do each of you consider essential?

Smith: In the studio, I just use what I use on stage—a 100-watt Marshall DSL and an American Strat loaded with DiMarzio pickups. Sometimes I’ll use Stevie Ray Vaughan singlecoils just to get a different sound. Kevin Shirley isn’t really into messing around with different amps and different sounds. Sometimes, in the past, I’ve recorded with just a guitar straight into a Marshall. I wanted to go back and try it with different amps and stuff, but I wasn’t able to because the band wants to keep it like a live setup. It can be a little frustrating, to be honest. For example, because you want to keep a pure sound straight into the amp, you have to compromise on the clean sound in the studio. Instead of getting a nice Fender Twin for a clean tone, you’d just use a Marshall with the guitar volume down, which isn’t really ideal.

Murray: I just got a Fulltone Deja’Vibe I really like. Also, using just a little bit of delay is nice for ambience, so it’s not completely dry. With Maiden, because there are three guitarists, you need to cut through everything, and having that ambience helps. And maybe a little bit of a chorus—anything that can add some spark and make it more musical and less flat.

Gers: A Marshall amp.

Adrian Smith and Dave Murray live at the PNC Bank Arts Center in Holmdel,

New Jersey, July 11, 2010. Photo by Rod Snyder

One of Maiden’s trademarks is your harmonized melodies. Since you started out as a two-guitar band and later added Janick, how do you arrange your two-part harmonies?

Gers: Well, you can do three-part harmonies.

Murray: Yeah, none of us ever stops playing— even if the other guitarists are playing a harmony. It could be rhythm guitar behind the harmony, or a unison part.

If it’s a harmonized line, would you do a unison on the upper melody note or the lower harmony note?

Murray: Boy, you’re asking some technical questions! It’s hard to answer that exactly, because when we learn and do a song in the studio, usually after we’re done, we just move on to something else and forget about it. There’s really no set way, it’s more of whatever works. There’s no formula. In fact, we try to step outside of formulas. Sometimes, if one of us has parts worked out already on a demo, we’ll just show the parts to the other guys. That way we can get it close to the way we had it on the demo. Or, sometimes we’ll make up a part on the spot.

Smith: Whoever brings the song in usually plays the main solo, and whoever figures out the best part to go with the solo will play that part.

Gers: Sometimes, if we’re playing the same thing, I might play a note, say, on the 3rd string and Adrian would play the same note on the 4th string, which thickens the sound out. I mean, if we really want to sort it out, I’ll say, “I’ll play in unison with you, but on a different string.” If you listen to those old albums, there are more than one or two guitars on it. On Tattooed Millionaire [Brduce Dickinson’s first solo album, released in 1990], I recorded eight guitars playing one chord, but at different levels—high, low, a chord in between, etc. If you mix them all together, it sounds like one big chord, but it isn’t. It’s all about making the guitars sound bigger, like a wall of sound. These are little tricks of the game.

What acoustic guitar did you use in the intro to “The Talisman?”

Gers: I did all the tracks for that. It was a Taylor, which was very lovely sounding. There were probably three or four acoustics mixed in on “The Talisman.” Some had different tunings. When we play it live, it’s just me on the acoustic, however. I have to play one of the parts, and you have to imagine the other. In these cases, I have to decide which of the parts to play, and which harmony parts to leave to your imagination.

Janick Gers summons a “wall of sound” live at the PNC Bank Arts Center in

Holmdel, New Jersey, July 11, 2010. Photo by Rod Snyder

How do you keep Maiden fresh, yet still distinctly identifiable, after more than 30 years?

Murray: Whatever that magic ingredient is, we don’t know—it just comes out of the air. We don’t tour as much anymore, and we record an album every couple of years. It’s just about doing something that you really love doing. For example, after Rock in Rio, we took a couple of years off. When you’re off, it’s good to just step away from the band stuff so that when you come back, it’s totally fresh. I would jam here and there. I jammed with Alice Cooper and Mick Fleetwood at a charity function, and that was a lot of fun.

Gers: We look at each other and feel each other, because to me, bands are all about chemistry. It’s not about the individual players. You can get the best players in the world and still have a shitty band if the chemistry isn’t there.

Smith, Murray, and Ger's Gear Box

Adrian Smith

Guitars—Two Jackson Adrian Smith signature models, Gibson SG, Gibson Les Paul Deluxe, S-style Jackson

Amps and Cabinets—Marshall JCM2000, Marshall 9200 power amp, Marshall 1960A 4x12 cabs with Celestion Greenback speakers, two Randall Isolation cabs with custom Celestions

Effects—Lexicon MX200, original Ibanez TS808, Dunlop Crybaby wah rack system controlled by Boss FS-5L footswitch

Miscellaneous—Rocktron Hush noise reduction, Tour Supply Inc. Custom Whirlwind rackmount MultiSelector footswitch, Yamaha MFC10 MIDI foot controller, Shure UHF wireless with UR4D receiver, Peterson tuner, Fender padded guitar straps

Strings—Ernie Ball (.009 .011 .016 .024 .034 .044)

Picks—Custom, heavy-gauge Ernie Ball

Dave Murray

Guitars—Two Fender American Standard Strats, 2008 Fender Dave Murray Signature Strat with Floyd Rose, sunburst Fender California Series Strat, 2010 Gibson Les Paul Traditional

Amps and Cabinets—Three Marshall JCM2000 heads, two backup Marshall 9200 power amps, two 4x12 cabs with 75-watt Celestion speakers, Marshall JMP-1 preamp

Effects—Fulltone Clyde Standard wah, Fulltone Deja’Vibe, TC Electronic G-Force

Miscellaneous—Rocktron All Access MIDI controller, Pete Cornish switcher, effects loop, and power supply, Korg DTR-1 rack tuner, Fender padded leather straps

Strings—Ernie Ball (.009 .011 .014 .024 .032 .042)

Picks—Ernie Ball .70 mm

Janick Gers

Guitars—Fender Strat, Gibson Chet Atkins electric/ acoustic

Amps and Cabinets—Four Marshall 9200 power amps, two Marshall JMP-1 preamps, Mesa/Boogie Studio Preamp, Marshall JCM800 Bass Series 4x12 cabs

Miscellaneous—Korg A4 effects processor (used as MIDI controller), Boss TU-12 tuner, Pete Cornish power supply and switcher/EQ, Pete Cornish cables, Ernie Ball straps

Strings—Ernie Ball (.010 .012 .017 .026 .036 .046)

Picks—Ernie Ball

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)