King Dude, known to the government as TJ Cowgill, has certainly made a unique space for himself as a musician and songwriter. A founding member and string-strangler in the death metal band Book of Black Earth, Cowgill began a solo career under the King Dude moniker with little in the way of expectations or direction, other than an affinity for the darkest regions of folk music’s past and an interest in the occult. Now on his seventh King Dude album, simply titled Sex, the former purveyor of tremolo-picked metal decimation seems more at home than ever crafting a genre-dodging blend of neo-folk, Goth-rock, and gritty roots music.

As the less-than-subtle title of Sex asserts, Cowgill’s latest work is an exploration of sexuality through the singer/songwriter’s Luciferian gaze. He’s the first to admit this is well-trodden fare. However, the Seattle-bred raconteur executes his missives on the topic with more than enough style and swagger to overcome any potentially trite moments, and there are spots on the exceptionally dynamic Sex that punch harder than anything found on his prior efforts as King Dude. In fact, much of the album finds Cowgill infusing his tried-and-true dark-folk songcraft with a heavy dose of early rock ’n’ roll’s piss and vinegar twined with the unhinged energy of primordial, late-’70s punk-rock—all hemmed with the cinematic, Ennio Morricone-informed twang and swirling sense of sonic drama that’s become one of the King’s calling cards.

Featuring a beloved budget-line electric Gretsch, a broken Martin acoustic, and some esoteric vintage solid-state amps, Sex is an immensely charming record that is as raw as it is thought-provoking and sonically unexpected. We asked Cowgill to detail his unconventional recording process, describe the disparate influences that went into the new album, and explain why he loves dead guitar strings and deliberately trashy sounds.

While the music you make under the King Dude name doesn’t have much in the way of guitar athletics, you have a background in extreme metal with your former band Book of Black Earth. Is it safe to assume you’re a relatively trained/athletic player when you want to be?

I would say that’s a half-truth. I think I’m a better guitar player than I might let on, but I’m not as good a death-metal or black-metal guitarist as most of the guys in that realm. I can’t really run those solos that people do in those styles—those sweeping things that sound like turkeys gobbling. I can keep up for sure, and I know some techniques, but King Dude is really about intuitive playing and a lot less focused on highly proficient, very fast playing. There’s a lot more in the way of dynamics. The quiets are quieter, which makes for more interesting music. If you bend a note with a Bigsby on a Gretsch, you just have to touch it, as opposed to, say, a Floyd Rose on a B.C. Rich, where you really have to jam it up and down. I appreciate the subtlety of this style of guitar playing a lot more.

Coming from the extreme metal world, was it a challenge to develop a sense of restraint when you started writing music as King Dude?

It wasn’t like a hard-stop kind of thing, in which I just swapped metal for neo-folk. They kind of ran alongside each other for a long time. I’ve played acoustic guitar in the same style since I was a kid, and the first song I ever learned on acoustic guitar was the Animals’ version of “House of the Rising Sun,” which I think is pretty indicative of my playing through-and-through. If anything, this is how I naturally play guitar and my death-metal and black-metal stuff is more attempting to emulate things I discovered later in life. Of course, everything is an emulation of something or derivative of something. I’m obviously not some ultra avant-garde Scott Walker type of guy, but when it comes to the transition between the bands, it’s not like I had to shake out what I was doing or what I had already learned. Also, there aren’t a lot of limitations in King Dude, so there might be a song that’s more upbeat or even has elements of my heavy-metal guitar playing in it. There is no limit to what I will do within King Dude, so if one day—and I hope it doesn’t happen—if I need to write a reggae riff for this band and it feels right for the song, I’m going to do it!

Sex is an evolution from past King Dude albums. It has a lot more depth than its predecessors, particularly with the inclusion of some proto-punk tracks like “Swedish Boys” and “Sex Dungeon (USA).” What pushed you in that direction?

The album is something of a pivot. Both of those tracks were inspired by a Swedish punk band from the ’70s called Leather Nun, which I had been listening to a lot at the time. Also, while the sonic influence might not be immediately apparent, I was listening to a lot of ’80s music, like Prince, Madonna, and even George Michael—which of course works extremely well for someone studying the subject of sex and how sexuality works in songs. George Michael’s influence might not come out sonically much on the record, but when you work on a topic that’s been trod so heavily, you have to be careful not to redo what’s been done and it’s good to look at the work of some of the best.

I’d say the biggest difference sonically from the last record is that this is the first King Dude album in which I’ve included bass guitar on almost every track. I started by writing bass lines first, which is something I never, never do. That shaped the sound of these songs.

On King Dude’s seventh album, Sex, TJ Cowgill has zeroed in on his music’s heart of aural darkness. He calls it a “pivot” in his stylistic evolution.

Do have a standard writing process? Do things typically start with guitar riffs?

Yeah, in the past everything has started on an acoustic guitar—my Martin, which I’ve had since [2014’s] Fear. But for this album, I picked up a bass first. I always try to put myself in a different writing territory, and if you’re always picking up the same instrument, you’re typically going to get similar sounding songs. Or at least it feels that way in my mind. So on [2015’s] Songs of Flesh & Blood, I started writing primarily on piano, and to make a change from that, the bass took the focus on Sex. I’d say 7/10s of the album started on a bass guitar.

Starting to write a song on a bass is the weirdest thing to me, and something I hadn’t done prior. I’m sure a lot of people have done it before, but it’s so restrictive with the amount of melody you can apply, at least for me as a player, that it becomes a very straightforward process. The upside I’ve found is if you can get a good bass line, you’re probably going to have a good song—unless you really fuck up in the guitars or something.

The bass guitar on the record is killer, and the tones you copped for the bass make up a huge part of the album’s distinctive sound. What gear did you use?

It’s all the same bass we use live—a $200 Fender Squier Jaguar bass. When I needed a bass to write with, I just went into a Guitar Center and picked up the cheapest but coolest bass I could find. I took the floor model home, and it is, for all intents and purposes, a total piece-of-shit. But I like it a lot.

I recorded in my own studio and also some of it was done at home, so each song is a little different. A lot of it was DI’d or played straight into the board or through a guitar amp. I don’t even own a bass amp. I like bass guitars to have a ton of midrange and be kind of clunky. I like the bass to have more attack and midrange poke so that it doesn’t muddy up my baritone vocals in the mix, because they do share a bit of range.

I love the tone of the surfy guitar stabs on “Sex Dungeon (USA).” What did you use when tracking them?

Those punched-in solos were done through my ’76 Fender Twin, and I was playing my Gretsch Electromatic Pro Jet. I think the key to that part is that it’s a production thing you hear on old punk records, where a solo just comes in way louder than anything else on the track and has a hard stop to it because it’s a punch-in.

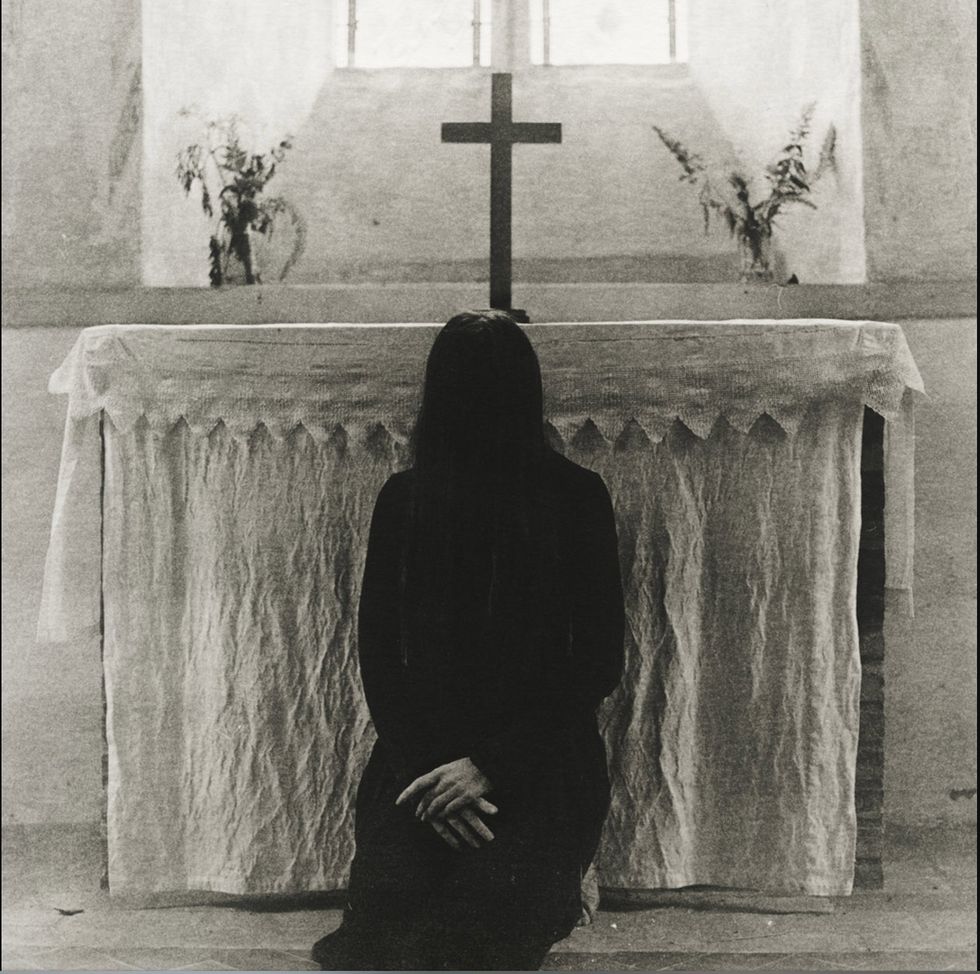

Seattle-raised guitarist TJ Cowgill adopted the King Dude pseudonym in 2006, when he began to envision his own dark but rooted take on American folk music. He gets plenty of mileage out of a Gretsch Pro Jet and an inexpensive Martin acoustic. Photo by Marie Magnin

Besides that ’76 Twin, were there other amps that played a major role in crafting the guitar sounds on Sex?

I pretty much stuck to the Twin, but I also have a $100 solid-state ’70s Ampeg GT-10. And I have two Heathkit TA-16 2x12 combos, which are super low-wattage solid-state kit amps from the late ’60s/early ’70s. You’d buy the parts and solder them together. Heathkit also made things like ham radios and home stereo receivers, but the same company, or guy maybe, also had a relationship with Vox and made the Jaguar kit organs for them. I just love these amps!

Even though the TA-16 is solid-state, the more you turn it up, the more gain you get out of it. And while they don’t get very loud, they give up this great, kind of shitty Rolling Stones guitar tone. Not that the Rolling Stones have a shitty guitar tone, but it’s like a shitty version of their sound. It’s great! And because they were handwired by amateurs who most likely did not really know what they were doing, each one sounds a little different. I’d like to get more, but they’re difficult to find. The other thing is, I don’t like buying amps on eBay because you never really know what you’re going to get unless you’ve played it in person.

Could you give an example of that amp’s tone from the album?

The lead guitar on “Swedish Boys” is all Heathkit, and “I Wanna Die at 69” has a bunch of it within its six guitar tracks. The song has, like, 29 tracks, which is insane for me. I can usually get out with under 10, but that one just needed so much action in the guitars. In fact, I think that’s the only song on the album without bass, because it was too dense with it. There were countermelodies I really wanted on that track, and I wanted this dirty black-metal tone on one side and a bluesy, sort of broken-radio thing on the other, so it’s got a bit of a stereo-pan going on in the guitars.

What guitar gear do you tour with these days?

I love Peavey’s stuff. They gave me a Classic 20 MH head and a 2x12 enclosure loaded with Celestions, and I actually think it sounds better than my Twin. It’s a low-wattage amp and it can scale down to 5 watts or even lower, which makes it really fun and versatile. It’s easy to get a good clean tone out of, which is important for me because I run pedals in front of it.

Describe those pedals.

I use a Wampler Black ’65, which I’ve had forever and is usually always on unless I need to get the amp really clean for a pretty song or something. I use it to condition the amp a little to make it sound more driven, but I like that pedal because if I’m on tour and using backline and they don’t have exactly the amp I want, that pedal is versatile enough that I can get the sound that I like with most amps.

I also use a Fulltone Supa-Trem, which is awesome and easy to use—which helps when I’m really drunk. Sometimes I have to adjust the speed of the tremolo and it has those giant foot-friendly knobs, which I love. And I just got the Earthquaker Devices Spires two-stage fuzz pedal that I’m really excited to add to my chain. It’s insane! It’s a little unwieldy with the second fuzz channel on, but it works well on songs like “Heavy Curtain” off the last album. I always had trouble getting that punchy solo at the song’s end to poke live, and I was using compression to push the signal for the solo, which was a terrible idea. So now I’m using a fuzz pedal instead and it’s working much better.

There are a lot of dramatic shifts in the use of reverb and atmospherics that really add to the record’s dynamic quality. Do you premeditate that stuff when you’re writing?

I don’t go in with a blueprint or anything, or even use a list, really. I just try to let the parts speak to me and I usually know when a part needs reverb or needs to be bone dry. And there is some weird shit that happens on these songs with chorus and flanging that is very intuitive to me, but probably very counterintuitive to most—at least in my methods and how I get there. I don’t know why people seem so afraid of doing stuff like throwing flanger on even just a bar of a guitar part to add some more character—make it ugly so the pretty parts can be prettier after, you know?

Could you give some examples on the album that define that sort of subtle dynamic approach?

On “Swedish Boys,” the beginning has a flanger, chorus, distortion, and just way too much shit on the bass, but it’s just during that little intro, and the rest of the song has a more conventional bass tone. For that minute intro, it’s all “what the fuck is this mess?” and it really kind of kicks you in the teeth. But when it comes together right after the intro, it’s much more dramatic because of it being juxtaposed against the mess.

I find if it’s an instrument you don’t normally play, it breaks your brain from the muscle memory habits you have—especially if you’re playing your go-to instrument, which for me just reminds me of all the stuff I’ve done already with it. But if I pick up someone else’s guitar, I find it helps me write stuff faster and more naturally. It’s good to switch out instruments often, and swapping guitars helps me write much better.

TJ Cowgill’s Gear

GuitarsGretsch Electromatic G538T Pro Jet

Martin OMCXAE

Fender Squier Jaguar Bass

Aria Pro II LP-style

Epiphone Les Paul

Amps

1976 Fender Twin Reverb

Vintage Heathkit TA-16 solid-state kit amps

Peavey Classic 20 MH Head and 2x12 cab

’70s Ampeg GT-10

Effects

Wampler Black ’65

Fulltone Supa-Trem

Earthquaker Devices Spires

Strings and Picks

D’Addario (.010–.046)

Various picks

The acoustic guitar plays a huge role on your albums. Tell us about the Martin you use, and any other acoustics that play a significant role in your music.

If you’re hearing an acoustic on a King Dude album, it’s that Martin. It’s actually one of the cheaper ones—the OMCXAE model, which is a composite-body guitar. It’s wood, but it’s coated with something that makes it almost feel like plastic. It’s matte black. I’ve toured all over the world with that guitar. It’s my go-to! I dropped it in Iceland once, had it fixed in Berlin by a great luthier whose name escapes me, but when I was in Greece, I forgot it was on my bed and I accidentally kicked it off the bed and the whole back fell off. I just taped it up and it’s been like that for about a year, and it still sounds good and holds in tune, so who knows? They say that Martins sound better and better with the more shitty things that happen to them. Look at Willie Nelson’s guitar.

There’s something about this particular guitar’s tone that I really love, too. All Martins tend to have a bass-heavy thing that I really like, but this one, being a bit smaller and having a composite body, has a really neat midrange going on. And it almost has a natural vibrato that’s hard to describe, but it has a wave in the chords that you can capture if you place the mic on it correctly.

The instrumental track “Conflict and Climax” adds a great bit of cinematic intrigue to the album. How did it come about?

It was one of the last tracks I recorded. I picked up a bass and came up with a bass line, which I then recorded just to remember it. I ended up liking the take, despite it being completely improvised, and the guitar track I layered over it was entirely improvised as well. They’re all the first takes and it’s a sparse track, and the only vocals are me screaming into the microphone on my laptop with a lot of room sound and feedback, so it was really easy to put together.

What about the Gretsch you use?

I use an Electromatic Pro Jet G538T in gold. It’s on the cover of my last album and I love it. It’s maybe a $700 guitar, retail, and it’s perfect for me. I don’t know why, but I prefer it over almost any other instrument in the room and I always go back to it. It’s my live guitar in the States, but I got an identical one in black recently that looks a bit more uniform with our live show. I use other guitars in the studio sometimes to get a different feel—like I have this shitty Epiphone Les Paul that I used on “Swedish Boys.” My mom gave it to me and it was a really nice gesture, but it’s not a great guitar. But I found uses for it. I also use an Aria Pro II Les Paul knockoff I found in a pawnshop for $200, and it’s got this super-hot pickup that I’ve used on records from time to time because it’s so good for overdrive. I couldn’t use that guitar live because of how out-of-control the pickup is.

The first Electromatic model I got was a hollowbody that’s based on the Country Gentlemen I bought as a conscious decision to try to look like Roy Orbison—wear suits and sunglasses and shit like that, because he was just so goddamn cool. I was really into shaping an aesthetic for myself, which went with changing things up from playing metal. The deeper I got into my craft, the deeper I got into the American rock ’n’ roll side of what I do, Roy included. I started researching the origins of American rock ’n’ roll and its origins in country blues and people like A.P. Carter and the rest of the Carter family, and even early field recordings, prison songs, etc.

Is your Pro Jet modified at all?

Nope! It’s bone stock. They send them to me and I don’t even change the strings—I just plug ’em in and play ’em. I probably do everything wrong in the eyes of guitar nerds, but I go months without changing strings. I recorded this entire album without changing my strings, which I’d say is half laziness and half that I like the way dead strings feel. I don’t care for the feel of new guitar strings, and I do think they sound a little too bright, but it’s really more of a feel thing for me. If one breaks, I’ll swap it, obviously, but I haven’t changed the strings on my Martin in well over a year.

YouTube It

King Dude’s key sonic signatures are featured on “Our Love Will Carry On” from his new album, Sex: atmospheric reverb, a widescreen blend of his Martin acoustic and Gretsch electric guitars, and his satanic baritone vocal intonations.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)