Muse’s eighth studio project, Simulation Theory, is essentially a concept album, addressing the ubiquitous nature of technology in our lives and the prospect of the simulation hypothesis—which poses that reality as we know it is an artificial simulation. Sounds ominous, but the band looked at this from a lighter perspective.

“This album deals with what it means to embrace technology and be positive about it,” explains the band’s frontman and primary songwriter, guitarist Matt Bellamy. “In the past, we made albums, like Drones, that were more resistant to the idea of technology, both in terms of the way we worked in the studio and also lyrical concepts. On Drones, we used our usual instruments and we didn’t bring too much technology into the creative picture. The concept of that album was all about our fears of drones, AI, robotics, and the future. Simulation Theory is, in many ways, actually a more optimistic view about what technology can do.” And so, in the studio, Bellamy and his cohorts, drummer Dominic Howard and bassist Chris Wolstenholme, harnessed that optimism by integrating a blend of real instruments, programming, and synthesizers. Lots of synthesizers.

“Think of it like the simulation of Muse,” he continues. “We pushed ourselves out of our comfort zone by finding ways for the instruments that we’ve traditionally used—guitar, bass, drums, and piano—to exist alongside more contemporary production methods.”

The result is a densely woven tapestry that mixes different genres and eras of music, and combines recording technologies into an incredibly cohesive, singular-sounding sonic masterstroke. On any given number on Simulation Theory, elements of synth-pop, hard rock, classical piano, and chiptunes abound and coalesce to form a highly original sound—from the sultry, subversive, Prince-like groove of “Propaganda” to the Primus-infused opening guitar riff of “Break It to Me.” The sheer magnitude of artistic exploration on Simulation Theory makes it abundantly evident why Muse has become one of the biggest rock bands in the world.

Adopting different working methods from album to album has been a hallmark of Muse’s career since they arrived in 1999 with their full-length debut, Showbiz. As they’ve evolved, Muse has been called “alternative rock,” “space rock” and “progressive,” among other labels, but somehow don’t fit neatly into any one of those categories. The release of their second album, Origin of Symmetry, in 2001, saw Muse adopt a more aggressive rock sound than their debut, whereas Absolution, released in 2003 and featuring their breakout single “Time Is Running Out,” featured prominent string arrangements and drew heavily on a different set of influences, including English actor-musician Anthony Newley and Queen. In 2006, Muse released Black Holes and Revelations, which reached No. 9 on the Billboard 200 albums chart. That release’s lyrical themes reflect their interest in science fiction and, musically, leans heavily on yet another set of more clangorous influences, including Depeche Mode and noise-rock auteurs Lightning Bolt.

Muse’s 2009 The Resistance earned their first Grammy for Best Rock Album and featured the ambitious three-part “Exogenesis,” recorded with an ensemble of more than 40 musicians. They released The 2nd Law in 2012, incorporating funk, electronica, film score music, and dubstep into their already otherworldly rock pastiche. Drones arrived in 2015 and saw them return to a more straightforward rock sound, and it, too, was awarded a Grammy for Best Rock Album. If there’s one thing that has come to define Muse over the past 20 years, it’s that they’re not content to simply replicate their success—even while maintaining it.

For Simulation Theory, Muse opted to write and record one song at a time for much of the album, and brought in an A-list team of producers, including Rich Costey (who previously produced the band’s Absolution and Black Holes and Revelations), Mike Elizondo, Shellback, and Timbaland. “This album was different in that each song had a different approach,” explains Bellamy. “There’s a handful of songs that evolved with the three of us working together—the more rock songs. ‘Blockades’ was done that way, ‘Thought Contagion,’ and ‘Pressure.’ But then there are songs like ‘Algorithm,’ ‘Propaganda,’ ‘The Void,’ and ‘Dig Down,’ which were written on the piano and synthesizer. I made demos of those songs that we then co-produced with the producers we were working with.”

Muse also thought outside the box regarding how their newest music would be released. The album’s 21-song deluxe version is only available online, via streaming platforms like iTunes, Pandora and Spotify, and features alternate versions of the 11 official tracks. “With streaming services, there isn’t really much of a limitation on how much material you can put out,” explains Bellamy. “You could put out a 30-song album if you wanted.” Historically, formats have dictated the length of a product. A vinyl LP is roughly 42 minutes or less. CDs go a bit longer, but the limitation is around 70 minutes. Bellamy and the band felt like streaming offered an opportunity. “Some of the alternate versions are more or less how the song was written,” he says. “For some people, this album contains a lot of synthetic processing, so I thought they might like hearing raw, untouched, stripped-down versions of the songs, with just me on piano or guitar.”

When pressed, however, another, slightly more altruistic reason emerges as to why Bellamy decided to include alternate renditions, and it demonstrates just how much he cares about the message he sends to Muse fans. “I did say in interviews a couple of years ago that this album would be more stripped down,” he confesses.

TIBDIT: Bellamy describes the new album as a “simulation of Muse,” due to its use of electronic music creation techniques and multiple collaborations with outside producers.

Bellamy says that comparing the album to the streaming tracks is “a way of showcasing how production alone can change the reality of a song—it can change the entire nature of how a song feels or sounds.” On some tunes, the alternate versions are so different they’re almost entirely unique entities. Consider “The Dark Side”: The album cut and “The Dark Side (Alternate Reality Version)” streaming version are almost completely different emotional enterprises. And “Algorithm,” on the album, harkens back to something like an ’80s film soundtrack, while “Algorithm (Alternate Reality Version)” sounds more akin to a Hans Zimmer score. And then there’s “Pressure” and “Pressure (feat. UCLA Marching Band),” which is pretty self-explanatory, but once one hears the latter, it’s surprisingly uncanny in how perfect the choice was to incorporate a marching band.

Bellamy was seemingly born to play guitar. His father is George Bellamy, rhythm guitarist of the Tornados, a band made famous for its chart-topping 1962 instrumental hit “Telstar.” Matt— born on June 9, 1978, in Cambridge, Cambridgeshire—formed Muse with classmates Howard and Wolstenholme at Teignmouth Community College in Teignmouth, Devon, U.K., in 1994. Since then he’s evolved into a bona fide guitar hero with a non-linear creative vision that’s taken Muse to the top echelon of rock, while driving the band’s sonic assault with his born-for-Guitar Hero riffs. Bellamy carries the torch brandished by the likes of Jimi Hendrix, the Edge, and Kurt Cobain—guitarists who’ve helped anchor the mighty riff into the canon of popular culture.

PG recently caught up with Bellamy in New York City, where he was fresh off of promoting Simulation Theory with a Muse performance of their single, “Pressure,” on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. To our delight, Bellamy candidly discussed guitar tones, amps, playing styles, and mods.

“I started with piano,” explains Muse’s Matt Bellamy. “I just played for fun at home—mostly blues piano and stuff like that. I got into guitar when I was about 12 or 13 years old. Again, I started out playing blues—a lot of slide-guitar stuff.”

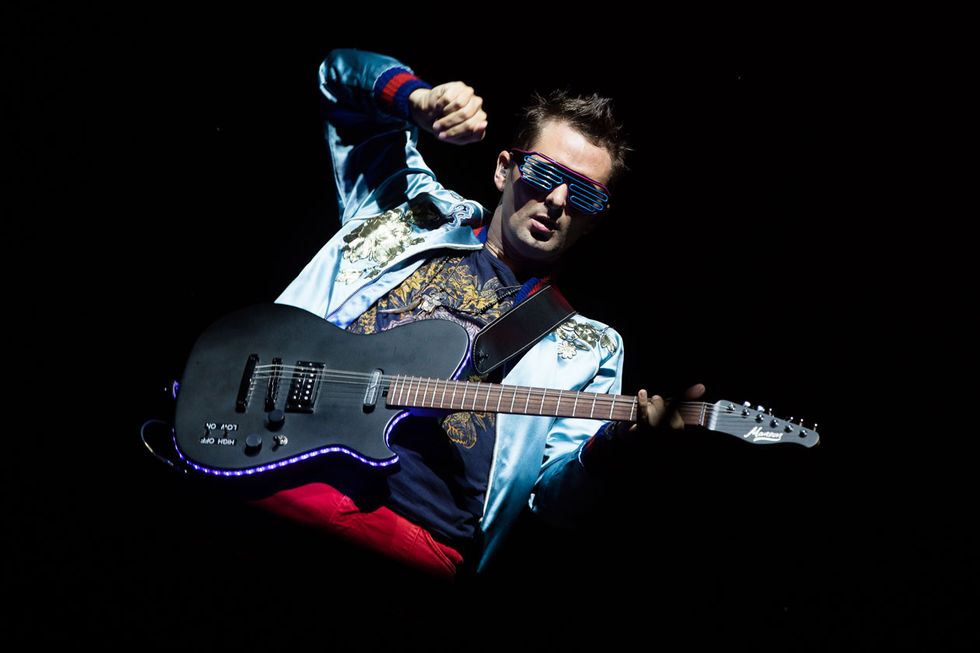

Photo by Debi Del Grande

There is such a wide tapestry of musical motifs on Simulation Theory. How complicated was it to figure all that out?

It was our intent to create a tapestry—that’s a good word actually—to deliberately meld together different eras of music, even within the context of one song. “Algorithm,” for example, contains a reference to both ’80s film soundtracks and ’90s computer-game music, but also, bizarrely, romantic classical piano. And so, it’s not easy, to try to put those things together [cohesively], but we set out with that intention—to blend different eras of music together in one song.

There seems to be so much going on at any given moment, and yet there’s space and breadth, and it all works—almost surprisingly.

I wouldn’t say we hit the nail on the head every single time, but that’s what we were going for. The song “Blockades,” for example, is pretty much transitioning between electronic dance music and, I wouldn’t call it metal, but heavy rock. That’s the kind of genre-blending we’ve done before, on our previous albums, but I think on this album there’s a few that we did that are new, like “Propaganda,” which is sort of funk/blues with some Delta-blues slide guitar. We wanted to try to find a way to mix that with contemporary Timbaland-produced R&B music and modern pop. Finding these unusual collisions, and I don’t think we’re unique in that way, is a sign of the times. The best music of this decade is from people who are splicing together stuff that is unexpected.

I hear a bit of a Prince influence in “Propaganda,” as well.

Oh yeah. I’ve always been a Prince fan. We had a song called “Supermassive Black Hole,” which was the first time that we dabbled with that kind of funk, blues-rock, but done in a more contemporary way.

When you’re weaving stuff together from different genres and eras, do you have a signal chain that you stick with for all the songs or are you mixing and matching guitars and amps based on the character of the song?

Over the years, I’ve experimented with so many different tones. On the Drones album, it’s pretty consistent, I’d say, but on this album, it was all about picking what was right for the song. There are even two songs that I play primarily on acoustic guitar, which is unusual for us. “Something Human” and “Propaganda” are both acoustic-based songs, but again, not acoustic in the traditional way, in terms of, like, stripped-down. They still have lots of layers of synthesizers, programmed drums and things like that. So that’s something that was different.

Do you have a go-to amp?

I tend to always use a combination of a Vox AC30 blended with a more metal-type of amp, like a Diezel—a high-gain amp—or my Marshall JCM800, which was modified by [NYC-based amp guru] Matt Wells to be a much more high-gain version. I like to have that combination of saturation with clarity at the same time. The Vox has a clearer tone and provides the clarity and attack, while the saturation and high sustain comes from the Diezel or Marshall. That’s always been my go-to and that’s what I tend to use live. On this album, however, there were some other things that were completely different. There are probably a few more DI guitar tones going on.

Sometimes you get a real nasal-sounding tone, like on “Pressure.” Is that from a combination of those amps?

That’s actually an Ampeg bass amp and, again, I can’t remember the exact model number, but I think it’s an ’80s era. [Editor’s Note: It’s a V-4B.] It has these switches on the front that allow you to filter out certain frequencies, which are aimed at bass frequencies, naturally, but Matt Wells modified it and made it so that it has more gain. I use that on the main riff in “Pressure.” It does have a really unusual, nasally, forward-sounding kind of tone. It lacks brittle, top-end attack, but it’s really useful for the placement of the guitar in certain songs, like “Pressure,” where you’ve already got a lot of brightness coming from brass instruments, Dom’s cymbals, and room mics.

The opening guitar part on “Break It to Me” has a very distinct “voicing” to it.

I very rarely use the neck pickup. I’m much more of a bridge-pickup bloke. It’s a very bright guitar sound. I think “Break It to Me” was primarily the Vox blended with another small combo amp that belonged to Rich Costey, and I don’t know if he told me what it was because it’s a secret [laughs]. You’d have to ask him. It’s some little, small combo amp made by a boutique maker in L.A. [Editor’s Note: Black Volt Amplification.] So, “Break It to Me” was that and a Vox, essentially for that guitar tone—very brittle, very bright tone, not very saturated. It’s almost like what it would sound like if you put an acoustic guitar into a distorted amp. It’s standard tuning apart from the low string, which is down to a B.

Are you using an effect on that intro riff?

I’m playing a dominant 7, sharp 9, like the classic Hendrix chord, but I’m bending it. I’m bending all the notes of the chord a quarter- to a half-tone as I’m hitting it, and then, after I hit it, I release the bend down to the standard chord and then just hit the low B string. It may be a little of our Primus influence coming through on that one [laughs].

Guitars

Cort MBC-1 Matt Bellamy Signature

Manson DR-1 Matt Bellamy Signature

Manson Metal Bomber custom build

Manson MA-2 EVO

Gibson SG Standard

Ampeg Dan Armstrong

Amps

Ampeg V-4B (modified by Matt Wells)

Diezel VH4

Marshall JTM45

Marshall JCM800 (modified by Matt Wells)

Black Volt Amplification the Crazy Horse (owned by Rich Costey)

Vox AC30

1970 Marshall 1960A and 1960B cabs

Mills Acoustics Afterburner 412A cab

Effects

Chase Bliss Warped Vinyl HiFi

Chicago Iron Tycobrahe Pedalflanger

DigiTech Whammy 5

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff

Eventide Space Reverb

JHS Pedals VCR Ryan Adams Signature Volume/Chorus/Reverb

JHS Pedals Colour Box Preamp

MXR Dyna Comp Mini Compressor

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball 2221 Regular Slinky (.010–.046)

Dunlop Tortex standard .73 mm

How was recording Simulation Theory different than previous albums, like Drones?

Previous albums were done the more traditional way, where you get in the studio and you work on a bunch of songs at the same time. With this album, the first three or four singles that we released, were actually recorded and finished one at a time. We weren’t working on any other songs. Weirdly, the song “Something Human” was recorded as the acoustic version first, which is on the deluxe version of the album. That was the first thing we ever recorded for this album, way back when we finished the Drones tour, and it didn’t get finished until a year and a half later. So that song was an extremely slow process. Some songs were done one at a time and we’d put all of our focus into that one song before we moved on to the next one.

Can you give us an example of how you incorporated using your usual instruments with synths during the writing and recording process?

With programmed drums, Dom would take over how that goes down by choosing all of the samples and making it work in a way that he likes to work. With songs like “Dig Down” and “Algorithm,” they often evolve into real played drums about halfway through the song. Towards the end of the song it’s full live drums. And with the bass, Chris would put his bass lines down and we’d often embellish them with synths. So, it’s different for every song.

What was your musical upbringing like? Are you a pianist who plays guitar or a guitarist who plays piano?

I started with piano. I never took lessons or anything. I was self-taught. I just played for fun at home—mostly blues piano and stuff like that. I got into guitar when I was about 12 or 13 years old. Again, I started out playing blues—a lot of slide-guitar stuff. In my teenage years, I went on a little journey where I started getting into rock and, bizarrely, got into classical guitar. When I was about 17 or 18, I took about six months of classical guitar lessons—mainly nylon string, flamenco guitar. That’s when I learned music theory. It was a really helpful time. At that point, I started playing piano again, and I got even more interested in classical stuff and interesting chord structures and moved away from the blues thing a little bit.

What are some of the challenges of singing and playing simultaneously?

In terms of singing and playing, the answer is … it’s very difficult [laughs]. For me, I try not to play really important rhythm parts on the guitar [when singing]. Rhythm-wise, I’m really relying on my drummer Dom, and then obviously Chris, to play really solid, important bass lines. The band was musically put together so that the songs could function with just the bass and drums. You’ve got the feel and you’ve got the rhythm, and the overall vibe from just the bass and drums. It allows me to come in with top parts on the guitar and vocal.

Are you intentionally crafting your rhythm parts so that they aren’t too restricting for your vocals?

Exactly. And so, in a live format, I’m inspired by a Jimi Hendrix or Kurt Cobain style, which is a bit looser and a bit wild around the edges. It’s almost like creating a scenario where mistakes are okay [laughs]. I wouldn’t be a very good funk guitarist, if I had to play those kinds of guitar parts and sing at the same time. I find it close to impossible. To be able to sing expressively, I need to be free and not be too restricted by having to play a rhythm part that is very precise. If you write the parts in the right way, it can work. With me, it’s a case of adapting the arrangements and the parts to fit the fact that I’m having to sing and play at the same time.

Is that why you often employ arpeggios?

I really like arpeggiation. It’s a method of adding two things. First, it adds harmonic structure. Secondly, it provides some rhythmic precision. So, sometimes the rhythmic precision of an arpeggio can outline the harmonic structure and add the 16s [16th-note feel] to the song, which means my guitar and my vocal can be a bit looser around the edges and not be too restricted by having to play in time.

Your solos tend to be very nuanced, melodic components of the song—almost like a song-within-a-song—yet there’s still something chaotic sounding about them. Are they improvised in the studio or pre-planned?

I’ve never been a very good improviser. I’m good at improvisation, if it’s chaotic. I can do crazy noises and throw the guitar around and create chaos. I’m good at that kind of improvisation, but I’ve never been good at well-informed scales and improvising in a jazz way or blues kind of method. Knowing the keys and the scales and just going for it and improvising melody and scales…. That’s never been my strong suit at all. Also, I’ve never been a particularly fast shredder. For those two reasons I tend to lean more towards melodic, simplistic lines that add a layer—almost like a continuation of a vocal melody. I don’t like solos that just repeat the vocal melody too much. That seems a bit pointless. To me the guitar solo is a chance to express a different melody, like having a guest vocalist singing a verse on the song.

In 2012, Muse played BBC Radio 1’s Live Lounge show, delivering the goods with effortless intensity. Watch Matt Bellamy, on one of his Manson signature models, uncork at 9:27 during the song “Uprising.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)