It’s an unseasonably cool evening in late July, but halfway into his set with the ever-stalwart Heartbreakers behind him, Tom Petty sounds perfectly at ease. “Wow, we’ve got a lot of singers out here tonight!” he marvels, his laconic Florida drawl unmistakable even after spending more than half his life in Southern California. The sellout stadium crowd in Queens, New York, hollers back its approval, and as he strums the opening chords to his signature hit “Free Fallin’,” the cheers build instantly to a roar that seems to compress the night air like an arm around your shoulder. Petty has likely played this song more than a thousand times since he released it back in 1989, but he still gives it everything he has.

It’s a testament to Petty’s fearless commitment to his music that he succumbed to a heart attack at his Malibu home on October 2, scarcely a week after wrapping up his 40th anniversary tour with the Heartbreakers—the band he cofounded back in 1976 with his childhood friends from Gainesville, guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboardist Benmont Tench. For Petty, music was as much a means of survival as it was expression, and while he certainly didn’t plan to go out on top, his last three triumphant nights at the Hollywood Bowl leave the lingering impression that he wanted it that way.

Petty’s hardscrabble upbringing in Gainesville was the early spark that drove him—that, and a chance meeting with Elvis Presley in 1961, when the star was filming in the neighboring town of Ocala. Three years later, the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, and 13-year-old Thomas Earl Petty was officially hooked on rock ’n’ roll. His first guitar was “an almost unplayable Stella,” as author Warren Zanes describes it in Petty: The Biography, published in 2015. “It wasn’t much more than a shape to hold, an idea with a strap. But it was enough.”

As a teenager, Petty threw himself into what was then a lively music scene in Gainesville. By 1970, he was playing bass and singing original songs in Mudcrutch, a Southern rock band with a country twist, with guitarist Tom Leadon, and lead singer Jim Lenahan. Before long, they were looking for a new drummer.

in rock history.”

“We went out to audition Randall [Marsh] at his house,” Petty recalls in the 2007 documentary Runnin’ Down a Dream. The band also needed another guitar player, and Marsh suggested his housemate. “And I heard him yell, ‘Mike, can you play rhythm guitar?’ And this voice comes back, ‘Uh, I think so.’ And into the room walks Mike Campbell, and he’s carrying this $80 Japanese guitar. At that point, we all looked at the ground like, ‘Oh no, this guy’s bound to be terrible.’ Mike kicks off ‘Johnny B. Goode,’ and after the song ended, I just said, ‘Hey, you’re in our band.’”

Tench soon joined the lineup, Petty took over lead vocals, and Mudcrutch became the buzz band in and around Gainesville. Eventually they signed to the indie label Shelter Records and relocated to Los Angeles, but when their 1975 single “Depot Street” flopped, Petty found himself at a crossroads, with the label asking to keep him on as a solo artist. Tench responded by booking a session to track some demos with Campbell and two friends from Gainesville—bassist Ron Blair and drummer Stan Lynch. He invited Petty to sing some vocals, and, within less than an hour, the Heartbreakers were born.

They weren’t an overnight success—not that success was of any immediate concern to Petty. As long as he could keep writing songs and keep the band together so everyone could make a living, he was content. On the strength of “Breakdown,” the brooding, soulful second single from his 1976 debut Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Petty had his first Top 40 hit, but it wasn’t until his third album, the monumental Damn the Torpedoes (coproduced with Jimmy Iovine and released in 1979), that he began to see his rock ’n’ roll dream as something real. With Campbell as his co-captain, Petty not only established the Heartbreakers as a quintessentially American rock band that could give the Rolling Stones or, for that matter, the Ramones a run for their money, but he’d written a nearly flawless collection of songs—among them the anthemic “Refugee,” the defiant “Don’t Do Me Like That,” the love-struck “Here Comes My Girl,” and the truly masterful “Even the Losers”—that held a timeless appeal for anyone who sought a deeper, more evocative experience from a 3-minute radio hit.

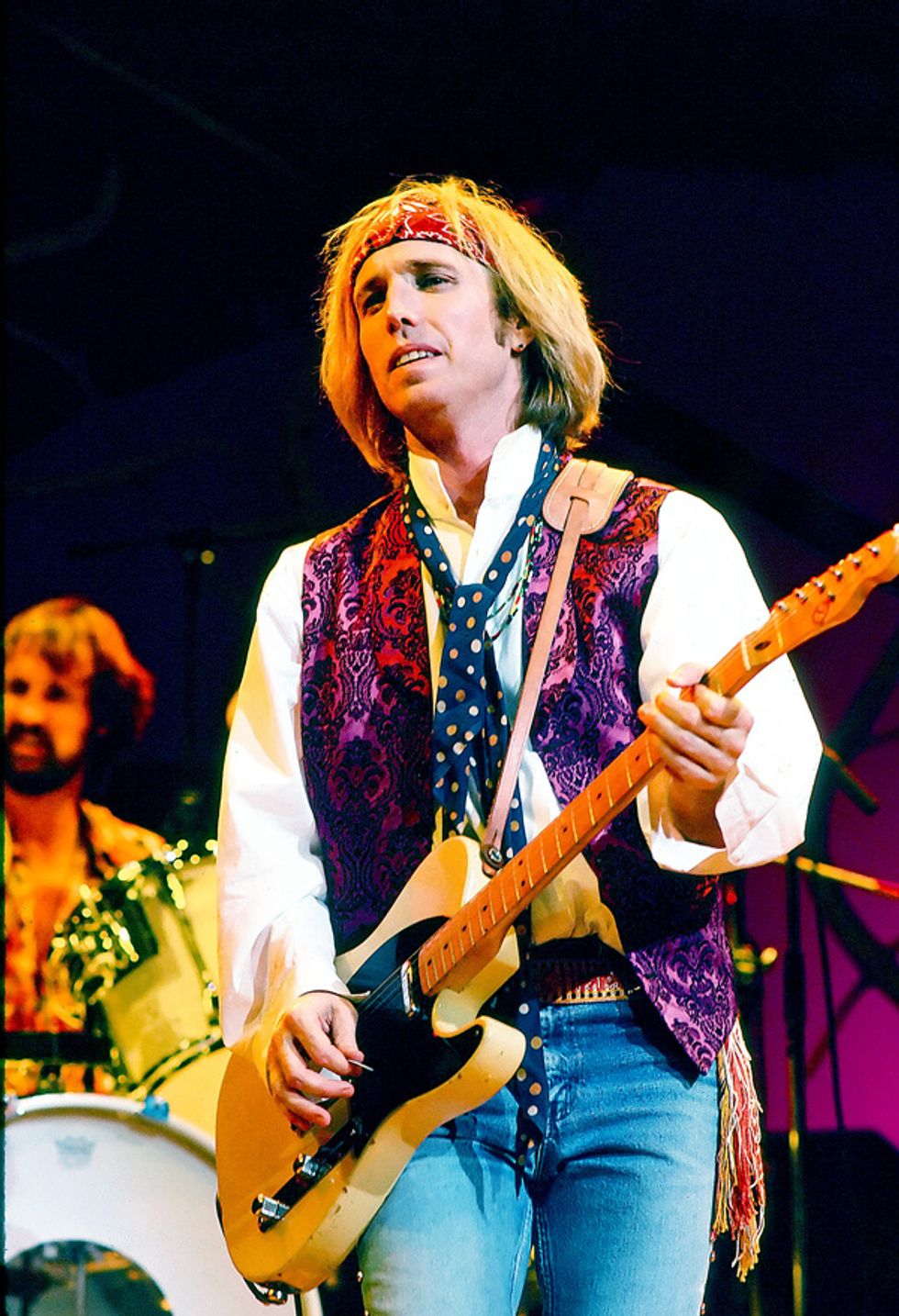

Tom Petty was a gear aficionado who loved vintage guitars. He also had a knack for transforming simple chord progressions into legendary tunes that continue to resonate through each passing generation.

Photo by Ken Settle

From there, at the dawn of MTV no less, Petty and the Heartbreakers went on an unprecedented run. Through six albums over a decade, from 1981’s Hard Promises to 1991’s Into the Great Wide Open (and including his classic 1989 solo debut Full Moon Fever, coproduced with Jeff Lynne and Mike Campbell), Petty honed his craft both as a songwriter and as a guitarist, prompting none other than Bob Dylan to refer to him as “a masterful poet.” While Petty’s songs seemed to capture a raw American and a particularly Southern spirit—ever-restless for meaning in life, always rebelling against conformity, always bypassing bullshit to get to the heart of any matter—he could transform a deceptively simple guitar figure, like the flatpicked opening to “The Waiting” or the leadoff chords of “Free Fallin’” or the changes in “You Don’t Know How It Feels” (from 1994’s milestone Wildflowers, with producer Rick Rubin), into something instantly touching and memorable.

By the end of 1987, after Petty and the band had spent most of the past two years on the road with Dylan, the wheels were already in motion for the Traveling Wilburys. That the supergroup included three of Petty’s childhood idols—Dylan, George Harrison, and Roy Orbison—didn’t seem to faze him, although Petty consistently opted for quiet modesty when in the presence of stardom; it was the cool-headed Southern rocker in him. But if his long journey with the Heartbreakers had made him a peer in the eyes of his heroes, for the rock intelligentsia, his two years in the Wilburys cemented his place in the pantheon.

In 2002, Petty and the Heartbreakers were voted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Petty himself never seemed comfortable with awards. He won three Grammys after being nominated 18 times, including Best Rock Album for his last two outings with the Heartbreakers, 2010’s Mojo and 2014’s Hypnotic Eye. But it’s clear the recognition of his fellow artists meant much more to him than any nod from the industry. His work with Stevie Nicks, Johnny Cash, the Byrds’ Roger McGuinn, and, most recently, Chris Hillman stands with some of his best—in large measure because he was so uncompromising as an artist.

And, of course, there are the guitars. Petty and Campbell are probably two of the most knowledgeable aficionados of instruments and amplifiers to ever play in a rock band together. Campbell’s Rickenbacker 620/12 was a frequent presence on early tours and on the iconic Damn the Torpedoes cover. But over the years Petty played dozens of vintage guitars—Strats, Teles (including a Torucaster, built by Toru Nittono), Firebirds, J-200s, Epiphone Casinos, Rickenbackers, and Voxes. He also was honored with a signature Martin and Rickenbacker—both 12-strings. Tone and feel were often just as important to Petty as a memorable chord progression, especially as he gained more experience as a producer.

For everything Petty went through in his life—and there was a lot, from the painful breakup with his first wife Jane to the near breakup of the Heartbreakers (in 1994, a combative Lynch was replaced by Steve Ferrone on drums), from the loss of longtime bassist Howie Epstein (who stepped in for Blair in 1982 and was fired in 2001, only two years before he died of an apparent heroin overdose) to Petty’s own struggles with heroin addiction and depression—he never gave up on the one thing that seemed to keep him grounded besides music, and that was family. When he reunited Mudcrutch in 2007 and again in 2015, many saw it as a way for Petty to get back in touch with his Southern roots, and to reconnect with friends who’d been like brothers to him since his childhood.

Tom Petty’s last performance was September 25, 2017, at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. He died a week later of cardiac arrest, but he was in top form belting out his longstanding opus “Free Fallin’” while playing his beloved Rickenbacker.

When looking back on his body of work as a whole, there’s little doubt that Tom Petty will be regarded as one of the greatest American songwriters in rock history. He could take a beautiful ballad like “Southern Accents” and make it bleed, or light up a hard-rocking slab like “I Should Have Known It” and make it burn. More than anything, his songs come across as raw and intensely personal, even if the meaning behind them sometimes feels mystical or mysterious. Whenever he carried a heavy weight—as a singer, as a songwriter, as an artist—he often made us feel that we carried it with him, and that’s what will make his music so accessible to the next generation, and the next.

“I’m doing the best I can,” he said in a 2014 interview with Canadian journalist Jian Ghomeshi. “You can’t say I didn’t try really hard, because I’m trying really hard to be good. Do I always hit what I was shooting for? No. There’s no great artist that hasn’t done some real shit. But you have to do that to maybe hit the stuff you’re trying to hit. It’s an ongoing challenge, but it’s a really enjoyable one, and it’s something I’m still pulled to. It’s a great little puzzle to work out. I’m just glad to have a job, to be honest, but I’m doing this for the music, and to hang around with my friends and play music with them.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)