Best known as the songwriting partner, guitar foil, and musical director for one Steven Patrick Morrissey, Boz Boorer wears many hats—all exceedingly well. He originally gained notoriety as a founding member and major creative force in the Polecats, one of the first and most important groups in England’s early-’80s rockabilly revival. Boorer joined Morrissey for the singer’s third solo effort, the 1992 epic Your Arsenal, which was produced by another world-class sideman, Mick Ronson. Since then, he’s played a major role in shaping the music the former Smiths’ frontman has made over the last 25 years.

Alongside his work with Morrissey, Boorer has maintained a prolific solo career while writing, producing, and recording with a multitude of other artists—often within the confines of his secluded Serra Vista Studio, in the mountains of Portugal. And when Boorer isn’t occupied creating music, he can frequently be found manning Vinyl Boutique, the record shop the apparent workaholic owns with his wife, Lyn, in the Camden Town area of London. Clearly, the man is a conduit for musical energy and undoubtedly a musical obsessive.

Boorer recently found the time to release his fifth solo album, Age of Boom, which has been more than four years in the making. A dynamic, sweeping work, Age of Boom juts in and out of the various sonic realms Boorer and his guitar have occupied over the years, and seamlessly ties the disparate sounds of its 14 tracks with whimsy and a wonderful cinematic sensibility. The album features an extensive cast of notable guest singers from the U.K. rock world, including Eddie Argos, James Maker, Tom Walkden, and Georgina Baillie, and is an excellent primer on Boorer’s versatile yet distinctive guitar work. His playing remains equally informed by the pomp and fire of ’70s British glam-rock, early punk, and an encyclopedic knowledge of rockabilly, which makes him something of a chameleon. He’s also an ace with effects. However, Boorer’s intent to serve the song first, whatever that may require, is obvious on Age of Boom, which flexes his writing as much as his genre-trotting licks.

Premier Guitar gained an audience with the perpetually busy and disarmingly affable guitarist as he prepared dinner at his London home prior to absconding to Portugal for a recording session. Boorer opened up about his excellent solo work, his background as a player, working with the legendary Morrissey, and how he stays so hungry after many years in the game.

Were the songs for Age of Boom written with their specific collaborators in mind?

The whole album got pieced together bit by bit, and I knew I wanted this record to be different than things I’ve done in the past. I thought that working with vastly different people would get that done and make for a very interesting album. Some of the people I knew beforehand and some I’d already worked with over the years—and some the record label suggested. So, it all just fell into place, really. Things were planned, but it wasn’t difficult. I didn’t come across any obstructions putting it together, even though it took a long time to do—almost five years because of how busy I’ve been! But eventually I had to stop tracking because I had enough tracks to call it an album.

The narrative of the album, especially the title track, deals with getting caught up in nostalgia, which, I think, is something guitarists are prone to do. You’ve done a remarkable job in your career mining the charming things from the guitar’s rich history, namely from rockabilly, without necessarily clinging to them or sacrificing your own voice as a player. Do you have a philosophy for pulling that trick off?

I might nod to the past, but I’m aware of that and I try very hard not to create the same track twice. I think I’ve done that all my life—avoided repeating myself. Guitar-wise, I normally start in a very honest way, with just a guitar and a small amp, like a Fender Champ, and let the sound suggest different shapes and melodies without overthinking the whole thing. Sometimes it doesn’t happen, but more often than not it flows and if you follow the natural path of it, you tend to get something unique.

You’re an important figure in the rockabilly revivalist world. Has that style remained interesting to you after many years exploring it?

Yeah, yeah, absolutely! I was talking to somebody the other night about just this, at a reunion at one of the rockabilly clubs I’ve been going to for 30 years now. It’s always been funny to me when someone renounces the music and says, “Well, I don’t like that anymore,” because for me, it’s been a big part of my formation as a musician since I was a kid. On the surface, it’s very simple music, but some of the playing is absolutely incredible and it’s also the roots of a lot of different sounds.

I also think it’s quite remarkable that it’s nearly impossible to recreate that truly authentic rockabilly sound accurately. I know loads of people try to make a record that sounds like it was made in 1956, and you just can’t do it! I mean, it frustrates me because I’d love to do it!

You’ve made a career supporting vocalists with texture and drama, but as a fan of rockabilly and glam—which so often feature guitar as a focal point—do you ever have difficulty reconciling subtle support and guitar heroics?

One bleeds into the other, really. It’s all in there somewhere, and some of it leans one way and some the other. Sometimes I think, when I’m playing a solo, “I don’t know where this comes from?” and it’s usually a Marc Bolan riff that I’ve made rockabilly or the other way around. But I don’t really think about it actively. I just play.

Do you have any advice for guitarists playing a support role or interested in delving deeper into using the instrument to build textures? How do you craft such parts as a composer and songwriter?

I normally start off with some sort of rhythm guitar, maybe a lick idea, but normally it’s a chord sequence. I like to use a compressed, light sound, which I then usually track out with an acoustic as well, to get that bright sort of jingle-jangle, or maybe even a Nashville-tuned acoustic—which I use quite a lot. [Ed–Nashville tuning requires a light, unwound set of strings with the G, D, A, and low E strings tuned an octave higher than usual.] I like to use a Nashville-tuned electric, but I don’t use it as much as the Nashville-tuned acoustic, which gives it that extra jangle without making things too thick. The other side of using Nashville tuning is that it suggests all kinds of great stuff—harmonics and different melodies start to make themselves known. It’s a lot of, “Oh, I didn’t think of that,” and you can hear different ideas—harmonies and runs—suggesting themselves in that tuning as opposed to standard tuning. I also often like to add a string pad on a synth beneath things to blow it up a bit, and then you have this whole platform to experiment over.

There’s a load of great classical-style guitar on Age of Boom. I hadn’t realized traditional nylon string was part of your repertoire. Is that something you’re well-versed in?

I learned the classical guitar stuff when I was a teenager, because I wanted to learn how to play more than one string at a time and I wanted to learn how to read more than one note of music at a time. I also wanted to do some of that country picking and I thought if I took some classical lessons, I’d learn how to better coordinate my fingers. So, I’ve been playing nylon-strung classical guitar since I was maybe 15. It’s all just a part of the bigger picture for me as a guitarist. I love to get the classical guitar out and play some of those old pieces—I keep the music out at my studio in Portugal and I have a really nice nylon guitar over there—but the truth is it’s just another gun in the arsenal, so to speak.

Could you tell us about the gear you used to track the album?

My studio in Portugal has a lot of stuff. For amps, I used a vintage Fender Champ a lot, a reissue Fender Bassman combo, and I have a big box of effects in there—really too many to list or recall. For guitars, I have a Japan-made ’50s Fender Telecaster reissue that got used a lot on the album and a 1960s Gretsch 6120 which made a lot of appearances. I have a Gibson Flying V that doesn’t get used much, and an ’80s Fender Stratocaster that also doesn’t get used much. There’s a recent Les Paul Special that I like a lot. I also used an Eastwood Sidejack, which a Mosrite kind of thing, and an old no-name Japanese copy of a Gibson Trini Lopez that has all its strings tuned to an E and usually gets played with a bow. For basses, I have a wonderful 1969 Fender Precision bass that I tend to use all the time, and I used a vintage Hayman bass from the ’70s that has a bit more bottom end on it. I also used a double bass quite a lot on the album. For acoustics, I used a Takamine and a vintage Epiphone … oh, and a vintage Gibson Melody Maker that I keep in Nashville tuning.

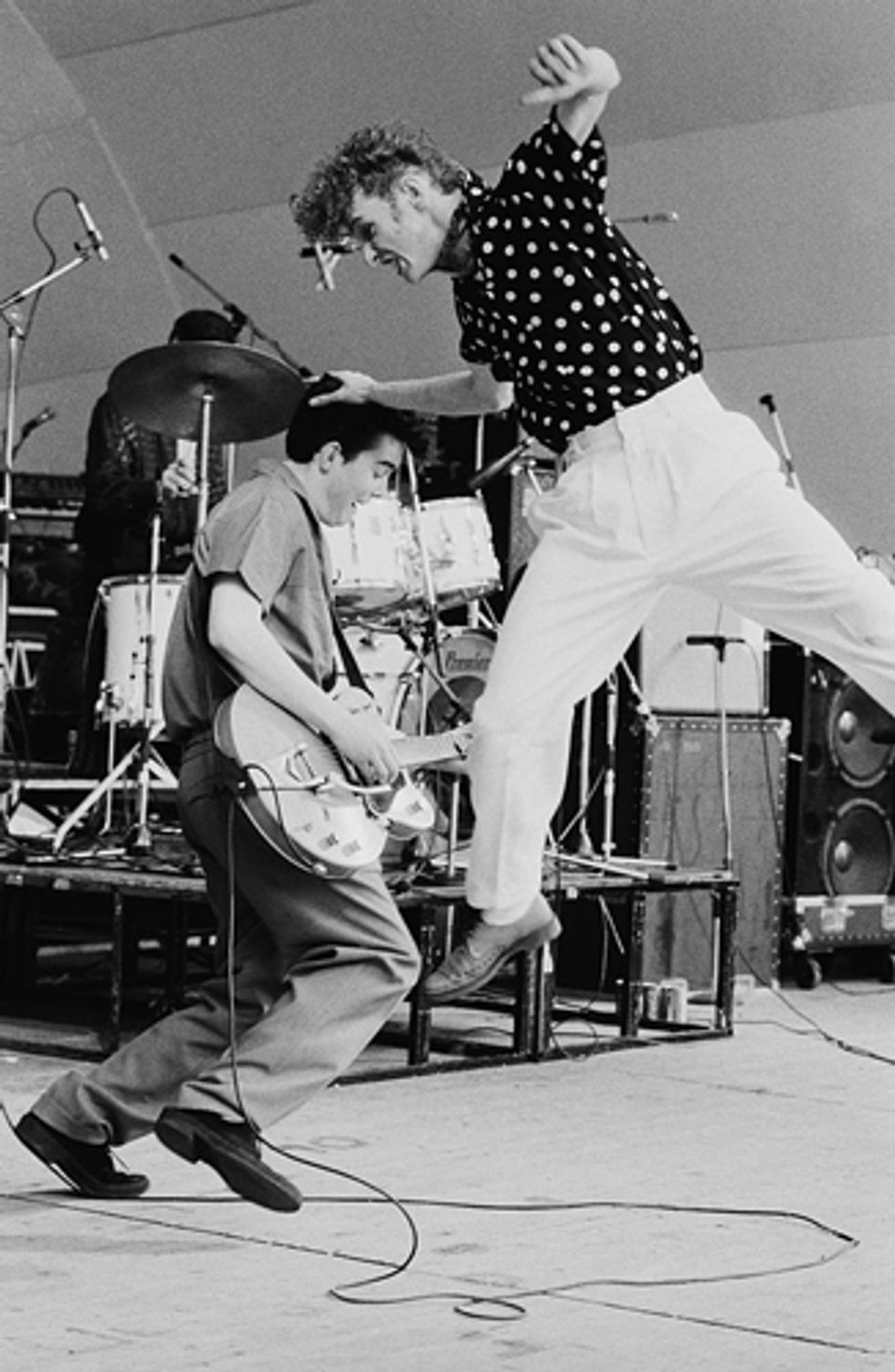

Boz Boorer (left) and Tim Polecat (Tim Worman) performing with British rockabilly group the Polecats, at the Summer in the City festival at Crystal Palace Bowl, London, in June 1981. Photo by Michael Putland/Getty Images

Tell us about your major influences as a guitarist.

It’s weird songs more than players, really. I’ve loved the Cramps since I saw them a few times in 1978 in London, and there’s some rhythms from Cramps records that I use a lot in my writing. I’ll write something and think to myself, “Now where did that come from?” and it’ll dawn on me that it’s from “Thee Most Exalted Potentate of Love” by the Cramps. That’s one rhythm that I use quite a lot!

Boz Boorer’s Gear

Guitars (Stage)

• 1963 Fender Telecaster

• Fender Mexico-built Telecaster

• Gretsch Silver Jet (tuned down a whole step, with flatwounds)

• Gretsch Custom Shop Shell Pink Penguin

• Gretsch White Falcon

• Dakota Raysik “Billie Pearl” custom

• James Trussart Steelcaster

• 1958 Gibson Les Paul Junior (tuned down a half-step)

• Maton BB1200

• Fender Kingman acoustic

• Gibson J-200

• Gretsch Rancher acoustic

(Studio)

• Japan-built Fender Telecaster ’50s reissue

• 1960s Gretsch 6120

• ’80s Fender Stratocaster

• ’70s Hayman Bass

• 1969 Fender Precision Bass

• 1960s Gibson Melody Maker (in Nashville tuning)

• Gibson Les Paul Special

• Gibson Flying V

• Epiphone Les Paul

• Japan-built Trini Lopez copy

• Eastwood Sidejack

• Vintage Epiphone acoustic

• Takamine acoustic

Amps

• Blackstar Artisan 30 (stage)

• Vintage Fender Champ (studio)

• Fender Bassman reissue combo (studio)

Effects

• Boss DD-500 Digital Delay

• Boss DM-2 Delay

• Boss TR-2 Tremolo

• Boss CE-1 Chorus

• Boss RT-20 Rotary Ensemble

• Boss BD-2 Blues Driver

• Boss RC-2 Loop Station

• Boss DF-2 Super Feedbacker & Distortion

• Boss CS-3 Compression Sustainer

• T-Rex Tonebug Phaser

• Boss AC-3 Acoustic Simulator

• Boss Reverb

Strings and Picks

• D’Addario and Jim Dunlop (.010–.052)

• Fender heavy

I love noisy guitars. Of course, I love the rockabilly thing with Scotty Moore, and Carl Perkins, and Les Paul, and fingerpickers—that stuff is obviously huge for me. Then there was the punk movement, with the Sex Pistols and Steve Jones. I swallowed Never Mind the Bollocks... when it came out in the ’70s and it was huge for me. Another big influence on my playing is John McKay from Siouxsie and the Banshees. That first Siouxsie record was quite incredible sounding, and it started me in thinking that music didn’t have to be any certain way—that there could be many different influences in music and it didn’t have to be a single, strict avenue. That first Banshees album has a lot of jarring guitar that rubs against what you’d think was going to or maybe should happen over a part, and that changed my thinking quite a bit.

I also studied harmony for four years and studied history of music for a long time as well, and there were weird pieces of music that I had to study for my exams in which I had to do things like take the “Trout” quintet by Schubert apart and rebuild it, and then write three parts of harmony beneath the top bar. I also played in an orchestra for three or four years, so I’ve done a lot of classical playing and understand music from that essential, fundamental perspective, too.

You’ve said that Marc Bolan was a major influence on your playing. What of his influence has stuck with you the most?

Well, it’s the little things. Usually he was quite simple, and he’d often end his phrases by slipping down to a sixth note, which I notice myself doing a lot. It’s never the plan, but I notice not a lot of people—if they’re in, say, E—slip down to a C#. Sliding down to a sixth isn’t a typical thing to do. That’s one major Bolan-ism that’s stuck with me.

I’ve read that when you and Morrissey work together, you typically bring in full-fledged compositions. Is there not much give and take?

Oh, no. Sometimes he completely rewrites stuff, changes the key, or asks for things to be added. He gets very specific about things, so there’s certainly a push-and-pull sometimes. Other times, they’re exactly as they are on the demo. It’s from all ends, and I have to say that it’s worked out pretty well for 25 years now!

With all the projects you’re involved with, how do you decide which ideas are best suited to be Morrissey tracks?

Well, I don’t—which means I have to write loads of songs and just keep writing! I have a big backlog of stuff that just sits there for a while, but they don’t really belong to any particular style of music, so the tracks always sound fresh. Of course, I would prefer to write for a particular artist rather than just pass songs around, which is something I did do many years ago because I had so many songs lying around. But I’ve found over the last 20 years that working with a particular artist and lyricist helps because of how that relationship works—where you can bring stuff out from them and they can bring stuff out from you.

I’ve always been intrigued by the symbiotic role of a guitarist as a sideman and foil to a frontman, and you’ve certainly developed that with Morrissey. Do you have any advice for those working as a guitar foil for a singer and building that relationship?

I don’t know exactly how to describe it, but it’s a way of listening and doing things in a sympathetic manner. Trying to hone in on and write things that are sympathetic to other people’s melodies and lyrics… It’s more a case of listening and finding ways to fit in, or finding something else in your head that has the same feeling as that which the singer is working around, and voicing that into the new thing you’re working on together.

Between owning a record shop, operating your studio, being Morrissey’s music director, your solo work, and various production and writing projects, how do you stay inspired?

I listen to all different kinds of music. I think that has a lot to do with it. I listen to classical music all night while I’m sleeping, so I’ve got those ideas flowing all night. I just found a wonderful punk band from Wales called Estrons that’s got a female singer that I’m really enjoying. I still listen to tons of old punk, old glam, and old rockabilly. I just try to listen to a lot of different types of music and stay in it, and listen to the things that I love to listen to. It doesn’t feel like work.

Also, working with Morrissey over the course of a 25-year career together, we’ve really not recorded the same song twice. It can be anything from a light and airy folk song to a dark and dingy progressive rock track, with anything in-between and any instrumentation, which is certainly very satisfying and freeing.

What was it like working with one of the best there ever was, Mick Ronson, on Your Arsenal? Did you learn anything from that experience?

Well, we talked earlier a bit about being sympathetic in your approach, and I think Mick’s whole self was sympathetic, in his approach to recording, writing parts, the sounds he’d come up with. The first time we played a track with Mick there, Alain [Whyte, former Morrissey guitarist and current cowriter] started playing through a Marshall stack exceedingly loud, and ol’ Mick just walked in the room and stood right in front of this huge amplifier while it was blasting and started playing with the EQ, finely tuning the thing. He was very hands-on. He also did all of those really great, really simple string parts on songs like “Perfect Day,” where it was maybe two violins in harmony. Very, very simple, but so effective and not really featured—occasionally they’d do a big swoop or something—but he knew how to write very effective things in a simple way. He had great little tricks, too, like when we did “Certain People I Know” he really wanted for the bass to sound Motown. So, they played it through my little Fender Champ, but he put a bit of sponge beneath the strings to stop it dead—which is something I still do! We did some great ambient recorder playing together on “We’ll Let You Know,” where we didn’t really listen to the track, and that was fun.

It was just a great experience. I had a lovely drive with him when he played at the Freddie Mercury tribute concert. He and I drove from the studio to Wembley and then back again, so to spend some time with him and just speak to him one-to-one was really nice. He was super into the Shadows and Duane Eddy; he loved twangy guitars. It was a joy just to be around him. The little things stick out more than recording stuff, like, in the morning we’d get up and both go through the racing forum and pick out our winners for the day and go down to the OTB and place our bets together.

YouTube It

Enjoy a quick guitar lesson with Boz Boorer as he explains how to play Morrissey’s “Irish Blood, English Heart” from 2004’s You Are the Quarry. On display: the song’s three core guitar components, Boorer’s mastery of delay, and a classy Gretsch White Falcon.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)