When this author met guitar maker Dan Becker in 2008, he said he had built fewer than 15 guitars. That estimate was surprising, because standing in his workshop meant standing beneath dozens of ornate guitars and guitar skeletons, elaborate unfinished models, and prototypes hanging from the ceiling. It was like being in a room full of nude mannequins, some without necks or bodies. It was impressive that such a small operation could produce so many pieces, and all by hand.

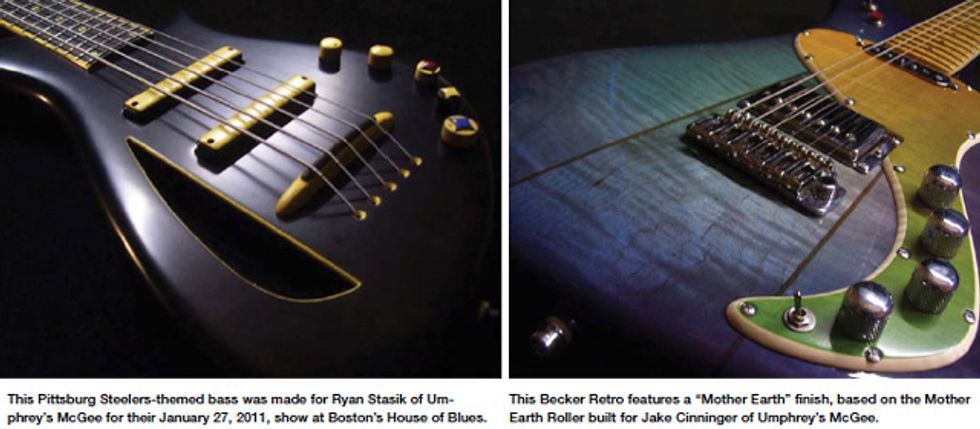

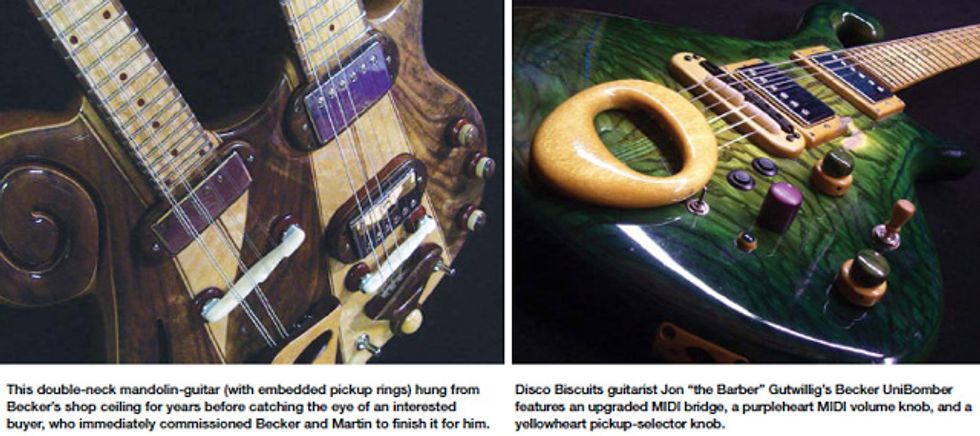

Becker and his business partner, Ryan Martin of Ryan Martin Basses, are unique custom builders who’ve based their reputations on quality craftsmanship and one-of-a-kind artistic designs. Using exotic colored woods and state-of-the-art materials, the two experiment with shape, color, and feel to create the custom stringed instruments they’ve come to collectively call ElectriCandyland. Each piece is carved, dyed, and finished entirely by hand. With the amount of attention put into each piece, it’s no wonder they’ve racked up an impressive list of professional clientele that includes guitarist Jake Cinninger and bassist Ryan Stasik of Umphrey’s McGee, moe. guitarist Chuck Garvey, and bassist Marc Brownstein and guitarist Jon “the Barber” Gutwillig of the Disco Biscuits.

“It’s really high-end craftsmanship in instruments done in a funky but elegant way,” Becker explains. “We use the word ‘psychadeligance.’ We’re not afraid to do our own thing, and I think people like that. ElectriCandyland is Alice in Wonderland meets Willy Wonka.”

The description is a fair one— Becker designs would be right at home in a Tim Burton flick. Each instrument is animated by vibrant colors and paired with an unconventional shape and design, and the designers say they draw inspiration from life’s smaller pleasures, such as Disney/Pixar films or Medieval Times.

Martin says the real challenge is designing something that’s unique, yet still has that familiarity guitarists expect. “Most good guitarists play a Strat or a Les Paul,” he says. “So if you make a guitar that feels better than a Strat or a Les Paul, it’s going to be undeniable, whether the artist is in the market for a new guitar or not.”

This bass is Ryan Martin’s version of a design by guitar maker

Robert Taylor. It’s made from purpleheart, bloodwood,

and curly maple, and features a high-gloss finish.

Life Changes

Becker Guitars’ wood shop in Attleboro, Massachusetts, is where the magic happens. The door to the shop is at the end of a long brick alleyway, and a tiny sign reading “Becker Guitars” is the only indication of what’s inside. More than 20 guitars are on display in the lobby, each one visually stunning and unique. The lobby opens up into the workshop, where dozens of works in progress hang from the ceiling while others wait for repair. Blankets of sawdust cover the tables and workbenches throughout the 5,000-square-foot shop. At the back end, garage-style doors are kept open in the summer months to let the breeze in. Becker and Martin have been there since 2006, after Martin decided to relocate from Maine to focus on guitar making.

Before opening his first small repair shop, Becker—who has a degree in finance—did a stint working for a financial advising firm, but his heart wasn’t in it. “I didn’t want to work,” he says. “I just wanted to play guitar—I work with my hands and can’t sit still.” One day as he sat in his cubicle, miserably watching the second hand on his desktop clock tick, suddenly he got up, walked out of the office, and bought a guitar magazine. Mentally checked-out for the day, he brought it back to his cubicle to read. The issue happened to feature custom guitar builders. As he drove home, he made up his mind: He would trade a career in finance for one as a guitar builder.

Becker than traveled to Michigan to learn luthiery and repair from a pro. “I went to this guy for a few months and learned just enough to be dangerous— I got my feet wet. But you can’t leave a school after a few months knowing what you’re doing.”

Although he was still new to the guitar business, Becker managed to land a job offer from Bourgeois Guitars in Maine, building acoustic guitars and working in the repair shop. The commute from his Attleboro home was tough— two to three hours each way. But Becker recognized a rare opportunity to get into a business he was passionate about and remained with Bourgeois for close to six months. Then, by chance, he met Pat DiBurro, whom he calls “the best repairman I’ve ever seen.”

Becker studied under DiBurro for a few years before branching out on his own, and he attributes most of his guitar-building knowledge to him. “When I went out on my own I learned a lot more, because there was no one to lean on—I had to figure it out. Now I’m super confident in what I can do, but it took years and years of a whole lot of instruments coming through my hands— thousands of them. So, I got good at repair and restoration, pulled Ryan down from Maine, and we started looking for a new shop.”

Before joining Becker in Massachusetts, Martin was living in Maine doing maintenance for his parents, who are landlords, but his real love was woodworking. Martin says he was changing out a toilet that wasn’t matching up with the floor properly when he had a revelation. “I was hugging it, trying to get the nut on the bottom to seat it to the floor, and I’m, like, ‘You know what? I’m a guitar maker. I ain’t doing this.’” Kneeling on the floor, he called his buddy Dan Becker. Becker laughs, “It took him hugging the toilet to realize he should come build guitars.” Since then, Martin says he’s been studying the methods of master luthiers Bob Benedetto and Carl Thompson.

Genesis of the Theme Park

In the years prior to the genesis of ElectriCandyland, the shop focused primarily on repairs, which helped Becker and Martin acquire a strong understanding of instruments and how they work. “Together, we were able to figure out how we wanted to build,” Becker says. “Now we’re developing ways to dress up our instruments and theme them out. We build several different models of guitars, basses, and mandolins, all with different themes that determine specifications and cost. We do fully custom work in addition to our standard lines, and our builds have trademark qualities like neck-through construction, comfortable, rounded body edges, 24-fret necks, and 14–16" fretboard radii.”

“It’s like a Choose Your Own Adventure book,” says Martin. “There are so many options— so many doors that you could open on any given day. We’re taking it to a redesigning level, and I’m trying to stretch the boundaries of what I can build. I like to bring in some weird stuff that Dan’s hesitant about. A lot of times I have to build it to show him, because he’ll see the sketch and say, ‘Nah, I can’t see it.’” But Becker says Martin is convincing him more and more—especially since a large part of their market is professional artists. “The most exotic guitars,” Martin says, “are the most quirky guitars. It’s a show business out there—we have to feed the need. If it takes inventing the market, we’ll make some funky, twisted shit.”

Martin and Becker clearly have a sense of humor and seem remarkably laid back, but they take their work very seriously. They lead a small crew but have the ambition of a full production team. Becker works days, and Martin, the woodworker, works nights. Martin first carves the shape and design from the chosen wood, and then passes it off to Becker, who takes the wood frame and transforms it into an instrument. He adds the frets and strings, oversees pickup winding, and then adds any additional color. “Sometimes,” Martin says, “I won’t see him [Becker] for a couple of days, and then I’ll see this batch of gleaming instruments . . . and I’m, like, ‘Oh yeah—Dan’s been at work!’”

The two built their first guitar—a “little mistress” they named “the Triple O”—in 2007. “We had only built the one guitar when we saw an ad that there was going to be a guitar show in Boston,” Becker says. They signed up for the show with one guitar and intentions of building an entire line in a few months.

The show was an enormous undertaking for the pair, who practically lived in their repair shop during those months. Night and day, they worked feverishly to create an entire line of guitars from one prototype. “We had to design the guitars, build them, and make hardware for them,” Martin says, “and we had no designs. But we talked about the Alembic—Jerry Garcia’s guitar— as far as visualizing the wood and the lamination.”

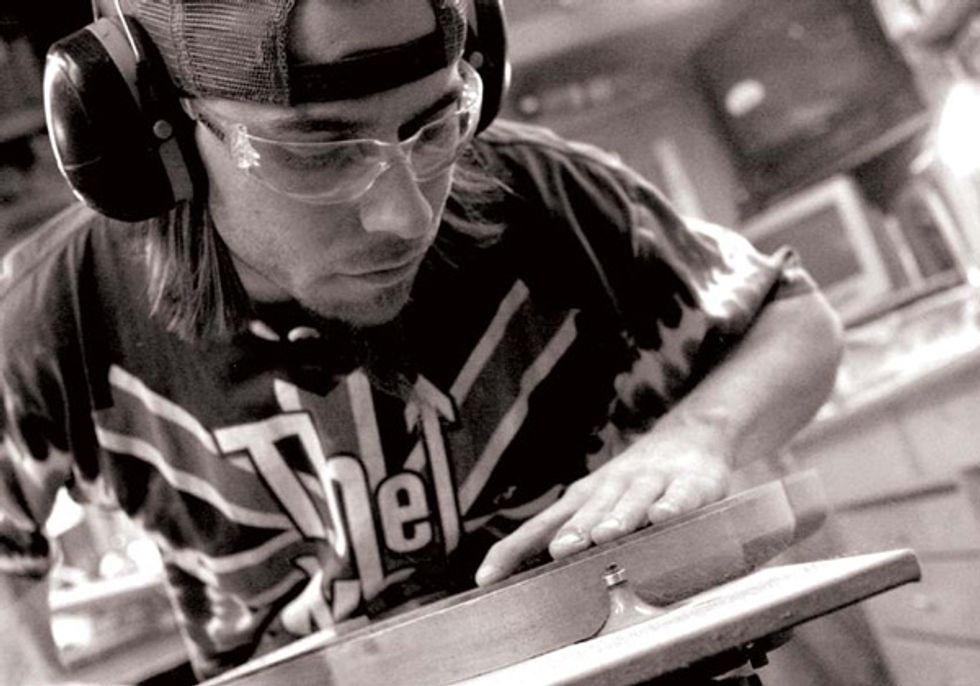

Martin working on the router.

Becker doing some fretwork in his and Martin’s Attleboro, Massachusetts, woodshop.

Endorsers Spread the Word

Since introducing their prototypes to the Disco Biscuits guitarist Jon “the Barber” Gutwillig at a 2008 show in Providence, Rhode Island, inquiries from other artists and fans have been steadily trickling in. “Barber opened a lot of doors for us,” Becker says. “As soon as he picked up the prototype, he goes, ‘Shit! This is so much better than my guitar!’” Gutwillig seized the opportunity to try something rare and played the guitar at that very show—and he hasn’t looked back since. “After that,” Becker says, “he took two of our guitars on the road with him while we built him his UniBomber.”

Gutwillig’s UniBomber is a green-and-purple piece from the Imperial line. Built from yellowheart and curly ash, the entire instrument was custom-carved— right down to the bridge, tailpiece, and knobs. Gutwillig says he was initially drawn to Becker Guitars because of the way the instruments play, emphasizing that the tone and playability is unmatched.

“They really don’t cut corners . . . and they go just as far to oversee the entire pickup winding process,” Gutwillig says. “To have two guys who are great builders not only look over the entire process of [building] the guitar—but also actually fashion all the little nuances of every single instrument— makes a big difference in things that are difficult to quantify, like sustain. I stopped using a compressor when I went to my Beckers,” he says.

A HeadHunter Roller in Black Cherry Burst finish.

Broadening Their Horizons

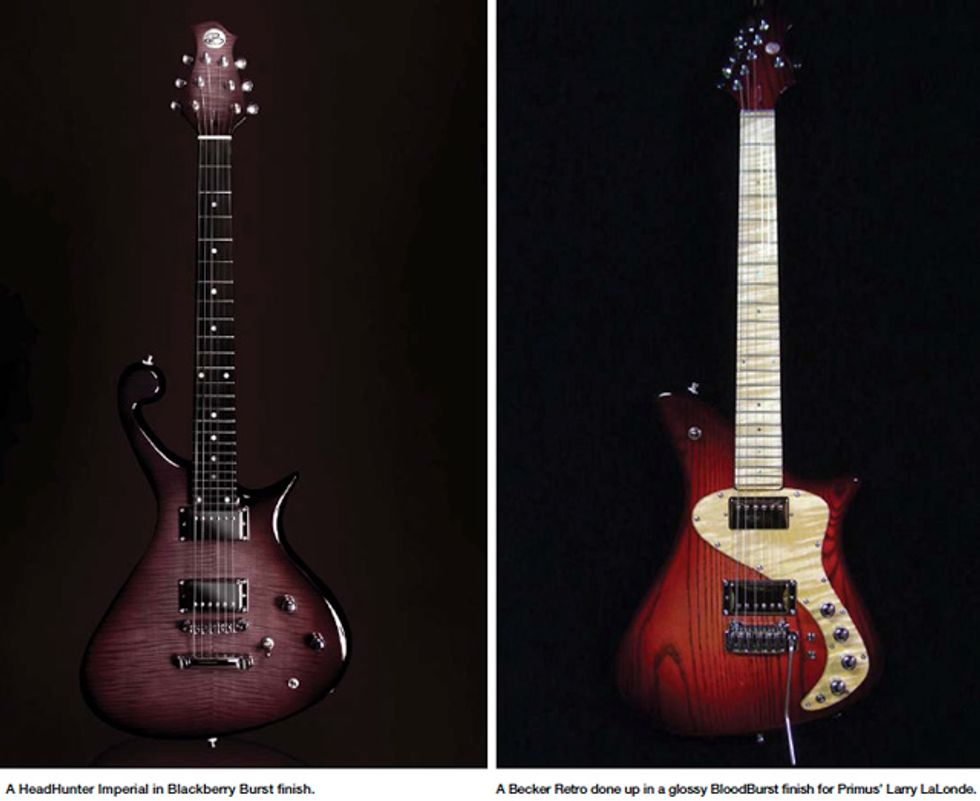

Today, ElectriCandyland is excited about the launch of two new production lines called the GhostRider and HeadHunter. Becker and Martin say the guitars are aimed at delivering the company’s signature tone and feel in instruments that are easier to produce and that will be more affordable. GhostRiders can be carved from mahogany or alder, their fretboards and retro pickguards are available in a bunch of different woods, and they feature more electronics configurations (such as coil-tapped humbuckers, P-90s, single-coils, and lipstick-style pickups) than any other models.

As for the HeadHunter, Becker says, “It will be one of the mainstays of the company: A neck-through instrument, all mahogany, with a maple top and an ebony fretboard. The woods are traditional, but the finish is very bold. We’re going to offer all of our guitar shapes in that style, which will be slightly more affordable.”

Dave Poe from the band Brew has already placed an order for his HeadHunter. Becker holds up a sweet-looking, deep-purple piece of mahogany with a curly maple top. Its heavily rounded edges give it a liquid feel. “It doesn’t have all the heavy lamination,” Becker says, “and we can build it much quicker because we don’t have to make the hardware—which takes a long time.”

With such low production numbers, most of Becker’s and Martin’s guitars and basses cost close to $5000. But the HeadHunter will run closer to $2000, and it was designed for those who want that “candy” without breaking the bank. “If we could produce the amounts that Fender or Gibson produce,” Martin says, “we’d be making a much cheaper guitar. But when you get to that level, you can’t give as much personal attention to each instrument and they all become cookie-cutter. Dan’s doing a good job of keeping them all different.”

One of the ways these intrepid builders keep their guitars unique is with wood choice and coloring. “We use a lot of exotic woods,” Becker says, “like bloodwood, yellowheart, curly ash, fever wood, cocobolo, and highquality, air-dried mahogany and maple. We’re always on a search.”

In a stroke of luck, Becker and Martin were offered a large stock of wood at a highly discounted rate by some retiring woodworkers. “We have a nice stash of 30-year-old, air-dried South American mahogany that’s really tough to get,” Becker says. “And we found another guy who was closing shop—a local guy—and he had a lot of old maple and ash.”

Each instrument’s vibrant color comes from the combination of the different woods and hand-dyed lacquers that are sprayed onto the body after it has been carved and sanded.

Becker explains, “When I asked a couple of players what color they wanted, rather than choosing a color [they] just gave me an idea to go by.” He picks up Poe’s guitar to make his point. “[Poe] said, ‘Just make my guitar Evil Excalibur.’ He goes, ‘Make it, like, forged from Mount Doom.’ I was like, ‘Freak! All right.’ I sprayed the back of the guitar cherry with black bursts, like a black cherry, and the front has grays, black, and purples—but it didn’t come out that evil. It needs to get darker. It’s all an experiment. Sometimes I don’t know how it’s going to come out, and then I finish it and think, ‘I hit it on that one.’”

Hoping for Hearsay

If you haven’t heard of ElectriCandyland, it’s probably because Becker and Martin rely on word of mouth as their primary marketing tool. “If we advertised,” Becker says, “We wouldn’t be able to keep up with our business.” Still, since 2007 they’ve sold close to 75 custom instruments, and you can now find them on Facebook, Myspace, and YouTube as buzz amongst guitar enthusiasts spreads.

“We’re under a hundred [instruments] right now,” Martin laughs, “so buy ’em while they’re rare.”

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig