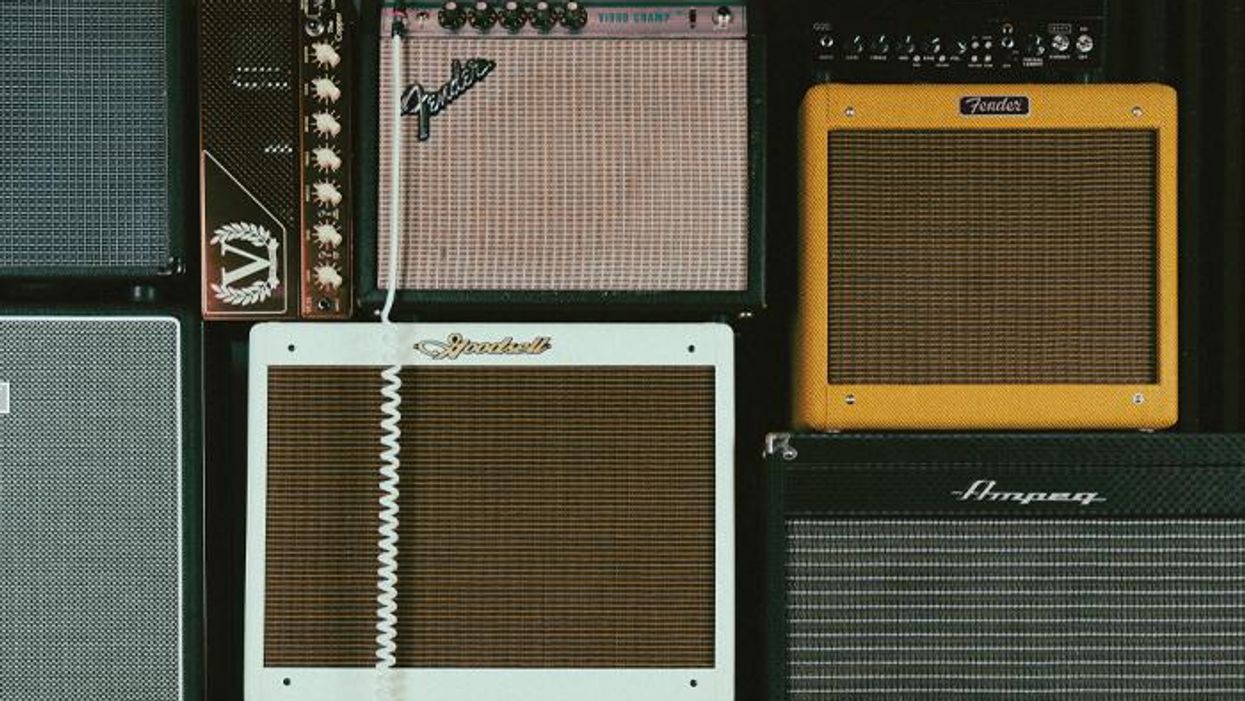

In our mad pursuit of boutique gear, it’s easy to overlook the humble speaker cabinet. While we drill down on the merits and specs of various speakers, the box that houses them typically takes a backseat to everything else in our signal chain. Which ain’t right, if you think about it. No guitarist is going to wow the crowd dangling a raw 12" speaker from a pole, right? The truth is, your cab plays as important a role as any other device in your rig, so it’s worth taking the time to explore it in its various forms. We’ll cover key points that will better acquaint you with what you already own and help you make an informed decision the next time you purchase a combo amp or extension cab. And while we’re at it, perhaps we’ll dispel a few myths.

Cabinet Material

If you ask guitarists what their cabs are made of, most will say “wood.” That’s the short answer, but it’s also very broad and incomplete. There are many different types of wood, and what a builder chooses will affect how the cabinet performs. Each type of wood has its pros and cons, and whether a cab has an open or closed back has a huge bearing on what a builder chooses to construct it with.

Many combo enclosures are made from solid wood—particularly vintage Fenders, which were built with solid pine. And since vintage gear is the gauge by which most new gear is measured, replica pine cabinets have grown in popularity over the years. Solid pine cabs typically have an open back, meaning the speaker is exposed to the air and thus delivers a more diffused and less directional sound. Solid pine is lighter than other cabinet woods and, as anyone who has lifted a combo amp knows, weight savings can be crucial—especially if you haul your gear to lots of rehearsals and gigs. But pine flexes, and this can emphasize certain frequencies. Because open-back combos don’t trap soundwaves, but rather allow them to escape, you don’t end up with resonant frequencies being accentuated by the cabinet walls. This explains why solid pine is ideal for open-back combos. Closed-back cabinets are more focused and directional, so it’s rare to find one made of solid pine, due to the aforementioned flexing and the sonic chaos it can bring.

Whether a cab has an open or closed back has a huge bearing on what a builder chooses to construct it with.

Most closed-back, or sealed, cabinets are constructed from plywood, as are some combos. The industry standard is 18 mm Baltic birch plywood, which differs from the sheets of plywood sold at the hardware store. To be a useful cabinet material, plywood needs to be voidless—meaning there is no trapped air between the plies. Unlike plywood used for less demanding tasks, Baltic birch plywood is made to be voidless, and this prevents the cabinet walls from rattling when you play. In Baltic birch plywood, each ply is a uniform thickness, laid with the grain alternating between north-south and east-west, and the boards are laminated with exterior-grade adhesives. The rigidity of Baltic birch plywood makes it an excellent material for closed-back cabinets, such as 4x12s and bigger 2x12s. Because of how it’s made, Baltic birch is nearly indestructible. However, this also makes it very heavy, which is why you see wheels on a lot of these larger cabinets.

You’d think the strength of Baltic birch would make it a good material for bass cabinets. Well, bass cabinets tend to need more rigidity than even Baltic birch offers, so they’re often made with chipboard or medium-density fiberboard (MDF). Both of these materials are extremely strong and have little-to-no flex because of the way they are made. Chipboard, sometimes called particleboard, is made by gluing together many different chips of otherwise useless wood scraps—and sometimes even sawdust. The chips are bound together with a resin and then drawn out into boards. MDF is made in much the same way, but, as its name suggests, uses much more finely broken-down wood fibers. This material is then pressed together with wax and resin at high temperatures. While the strength of these engineered materials is very high, so is the weight.

As a general rule, to do justice to the low frequencies of bass, mass wins. You need all that physical weight to help produce a burly low end. But there’s a downside to these man-made materials: They can deteriorate over time with heavy use, such as banging the cabinet against every stair as you hoist it up three flights to play for those 10 people.

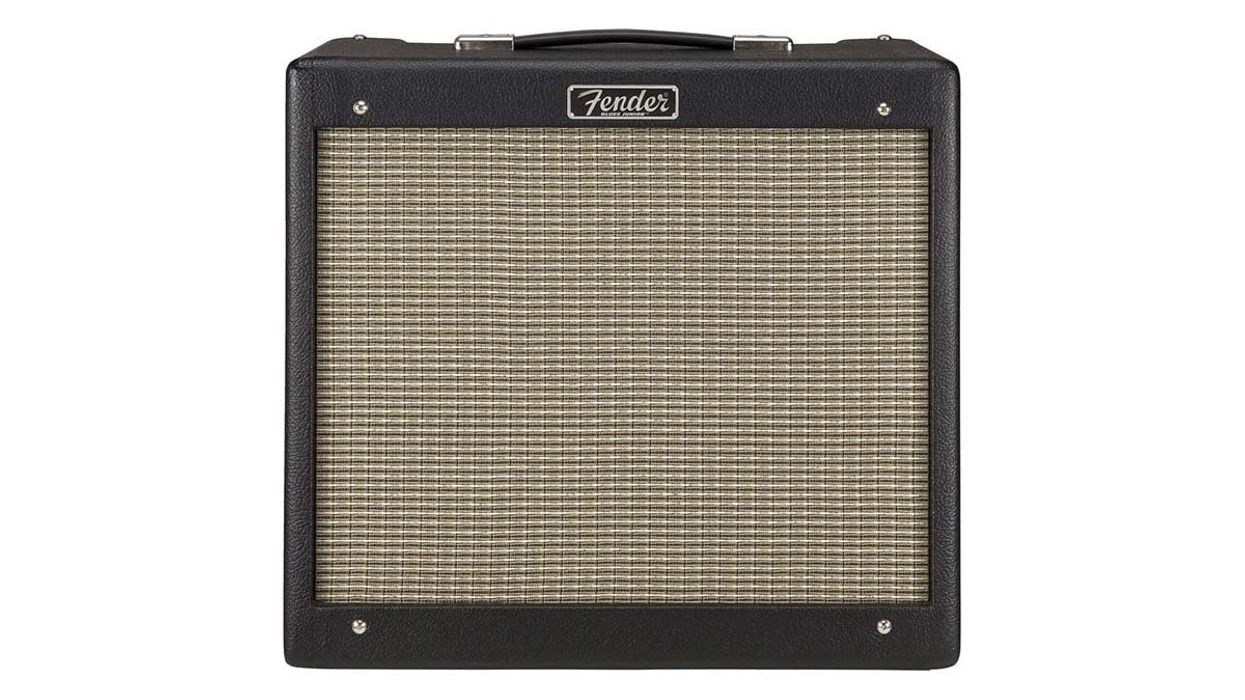

Many combos have medium-density fiberboard cabs, which are sturdy but heavy. Some players opt to re-house their combos in aftermarket enclosures made of solid pine—the wood Leo Fender originally used. Available for popular models like this Fender Blues Junior, pine cabs look cool, shave pounds off the combo’s total weight, and arguably enhance the amp’s tone.

Photo by Andy Ellis

Cabinet Joinery

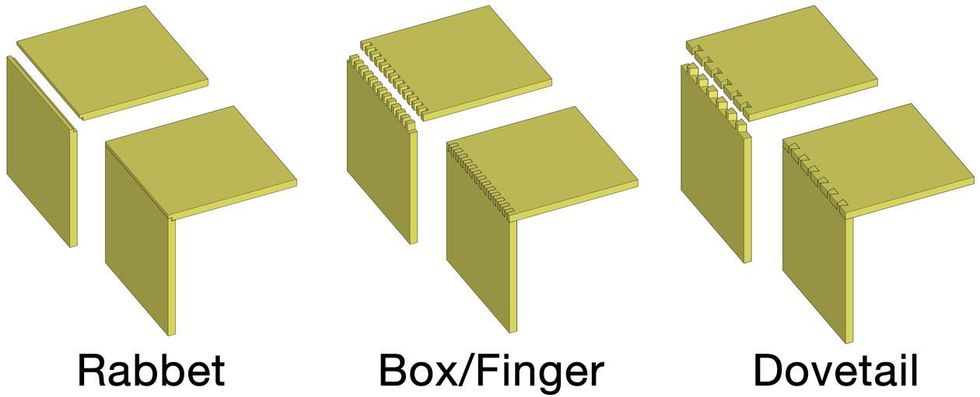

I’m sure you’ve heard a lot about different types of corner joints and how the joinery method impacts the cabinet. There are three main types of joints: the rabbet joint, the box or finger joint, and the dovetail joint.

The three types of joinery used for building speaker cabs. Dovetail joints are the strongest and are most often found on high-end cabinets with exposed, stained wood.

Diagram by C.J. Sutton

As you can see in the diagram, these are quite different from each other, but it’s important to note that unless the joint is made poorly and allows the corners to flex, the joinery type has virtually no effect on the sound. Rabbet joints are the most commonly used in domestic cabinets because they are fast and easy to execute, and they’re strong. Finger joints are the most sought-after because that’s how Leo did it in the ’50s and ’60s. These joints are stronger than rabbet joints and reduce the potential for flexing. The strongest of all is the dovetail joint. Good dovetail joints can hold together without any glue, but don’t worry—no one actually builds speaker cabinets with unglued dovetail joints. You’ll see dovetail joints on higher-end cabinets, particularly those made of stained wood with visible joints that are part of the look.

The Baffle

The front part of the cabinet where the speakers mount is called the baffle. It needs to be the strongest and most rigid piece of all because this part of the cabinet is subject to the most impact stress. Baffles are nearly always made with Baltic birch plywood, or in some cases even MDF—even if the cabinet walls are made of solid wood, such as pine.

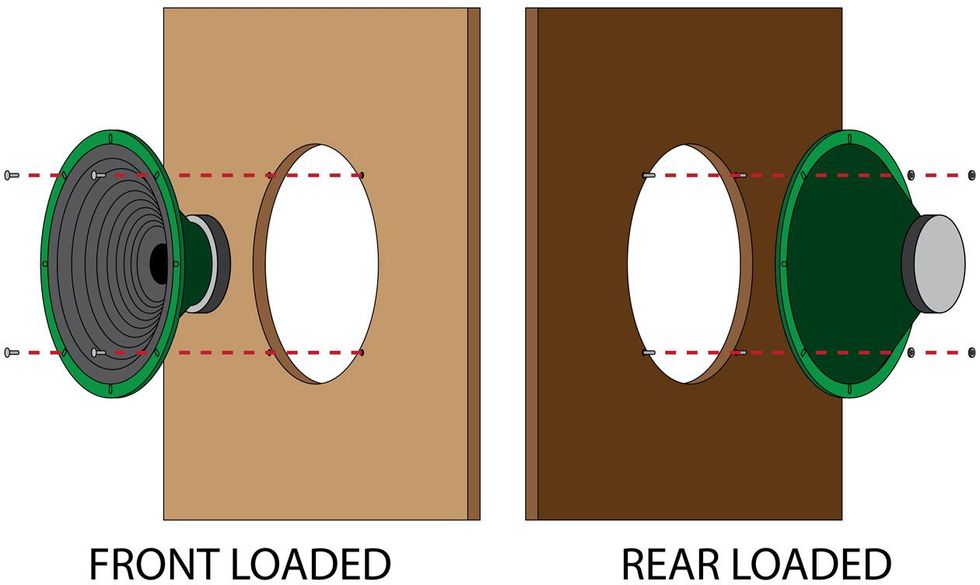

There’s a lot of hubbub about whether speakers should be mounted to the front or rear of the baffle. When a cab has a front-loaded speaker, the grille is removable to allow access to it. Front-loaded speakers are found most often in bass cabs and ported guitar cabs, where the back of the cab is designed for rigidity and is not removable. A rear-loaded speaker attaches to the back of the baffle, which you access in closed-back cabs—such as a Marshall 4x12—via a removable back panel. Most open-back combo amps also sport rear-loaded speakers.

The rigidity of Baltic birch plywood makes it an excellent material for closed-back cabinets, such as 4x12s and bigger 2x12s.

The theory behind front-loaded speakers is that they don’t seal up perfectly to the baffle and thus allow air to escape, which adds some musicality to the sound. Also, in a recording situation, it’s easier to swap out front-loaded speakers in a quest for different tones. Conversely, rear-loaded speakers can be more of a pain to replace. In closed-back cabs, you have to remove the entire rear panel. If you’ve ever opened up a 4x12 cabinet, you know there are a lot of screws involved in securing that back panel. And if you’ve ever decided to take a shortcut and not put all the screws back in, then you know about the potential for ugly rattling.

A side note about 4x12 cabs: Some have posts inside that connect the center of the baffle to the rear panel. These baffle posts are designed to offer additional support and create one more connection point to keep the rear panel from flexing.

Speakers can be attached to either the front or rear of the baffle. Front-loaded speakers are accessed through a removeable grille; rear-loaded speakers are housed in open-back enclosures or in closed-back cabs with a removeable rear panel.

Diagram by C.J. Sutton

Before you can access the rear-loaded speaker in some open-back combo amps, you first have to remove the chassis. This means virtually disassembling the entire amp. Please note: Never stick your hand inside an amp chassis. There can be lethal voltages present even after the amp is turned off and unplugged.

So is one speaker-mounting method superior to the other? That depends on what you’re after: Rear-loaded speakers form a tighter seal to the baffle and provide a sound that works well with rock ’n’ roll and heavier music, and front-loaded speakers can sound airier. But there’s no right or wrong. My friend Jason Jordan of Monarch Cabs says it best: “It’s all a matter of preference, really. What guitarists think of as a “good” sound is based on the music they listen to. As builders, we have formulas for making speaker cabs sound a certain way. It is a science. But at the end of the day, you need to experiment and listen, and then simply go with what works for you and your playing.”

Although the vast majority of amp cabs have either an open back or closed back, it is possible to have both. This 4x10 Marshall cab has been professionally modified to be configured either way, depending on the size of the stage and the band’s music. If you’re considering doing this yourself, the trick is to cut the back panel into thirds and then completely wrap each piece in “cab carpet.” This creates a super-tight fit between the panels and prevents rattling. In closed-back mode, tour-case latches hold the middle section securely to the fixed top and bottom pieces.

Photo by Andy Ellis

Cab Placement

So what happens when you want to take your rig public? What should you consider when placing an amp or cab onstage? The answer depends greatly on whether the cab is going to be miked up or not. If it is, then the cab can really go anywhere. To keep the stage volume down, many bands face their cabs backward—or even remove them completely from the stage—because the miked sound will be fed back through the monitors, which can be either onstage wedges or in-ear buds.

If you’re not miking your speakers, and the sound from the cabinet is the sound the audience will hear, it gets a bit trickier. You have to position the amp so you can hear it while you’re playing, yet the audience also gets a good mix. If your cabinet has wheels, you might find that popping them off or setting the cab on its side increases low-end resonance through greater contact with the floor. But this stage coupling might introduce muddiness into the band’s sound—exactly what you want to avoid. It depends on the stage and room, and each venue is different. The way to tame unwanted rumble is to reduce contact with the floor, perhaps by using an amp stand, or keeping the wheels attached to your cab, or placing it on the rolling bottom of a road case. Wheels offer another advantage: They make it easier to move your cab around during soundcheck until you find the sweet spot where you, the band, and the listeners can all enjoy your cosmic licks.

Some amp cabs are designed not to be heard—at least by anyone in the immediate vicinity. Such sealed “speaker coffins” have an internal mic clamped to a gooseneck to allow for precise positioning. Accessed through a hinged trap door, the mic connects to a recording console or front-of-house mixer via an external XLR jack. Notice how the Celestion Greenback in this Demeter Silent Speaker Chamber is front-loaded to facilitate quick speaker swaps.

Photo by Andy Ellis

Visual Vibe

Some players swear the cab’s covering material—or even its color—and grille cloth have an effect on tone. In my experience, I haven’t noticed any evidence of this. Certain grille cloth materials, such as cane, are more rigid than others, and this could potentially influence the sound, but essentially grille cloth choice is cosmetic and if it has any effect at all on tone, it’s very slight. By the time the drums get pounding and you’ve cranked up your amp in response, it’s the speakers you’ll be hearing, not the grille cloth. And if you think a cab wrapped in red or green vinyl sounds better than black Tolex, who’s going to dispute that? After all, you might actually play better because you love the way your amp looks.

By the time the drums get pounding and you’ve cranked up your amp in response, it’s the speakers you’ll be hearing, not the grille cloth.

While some players agonize over the thickness of the grille cloth or cabinet covering material, there’s little evidence these cosmetic details have any significant effect on tone.

Photo by Michael Silva

Eyes On the Prize

When it comes to gear, my motto has long been “if it sounds right, it is right.” Once you understand the basics—wood, construction details, and how speakers are mounted—it’s then a matter of putting in the hours with different types of rigs and amp cabs.

In the process, you’ll develop an instinct for what sounds best with your guitars, technique, and musical style. And this is where the fun begins. My advice? Don’t stress over little things like what type of corner joints you have. Just get out there and play!

If you’re not miking your speakers, and the sound from the cabinet is the sound the audience will hear, it gets a bit trickier. You have to position the amp so you can hear it while you’re playing, yet the audience also gets a good mix. If your cabinet has wheels, you might find that popping them off or setting the cab on its side increases low-end resonance through greater contact with the floor. But this stage coupling might introduce muddiness into the band’s sound—exactly what you want to avoid. It depends on the stage and room, and each venue is different. The way to tame unwanted rumble is to reduce contact with the floor, perhaps by using an amp stand, or keeping the wheels attached to your cab, or placing it on the rolling bottom of a road case. Wheels offer another advantage: They make it easier to move your cab around during soundcheck until you find the sweet spot where you, the band, and the listeners can all enjoy your cosmic licks.