Working from a shared language of elegance and grit, Nashville guitar domos Tom Bukovac and Guthrie Trapp have crafted In Stereo, an album that celebrates the transcendent power of instrumental music—its ability to transport listeners and to convey complex emotions without words.

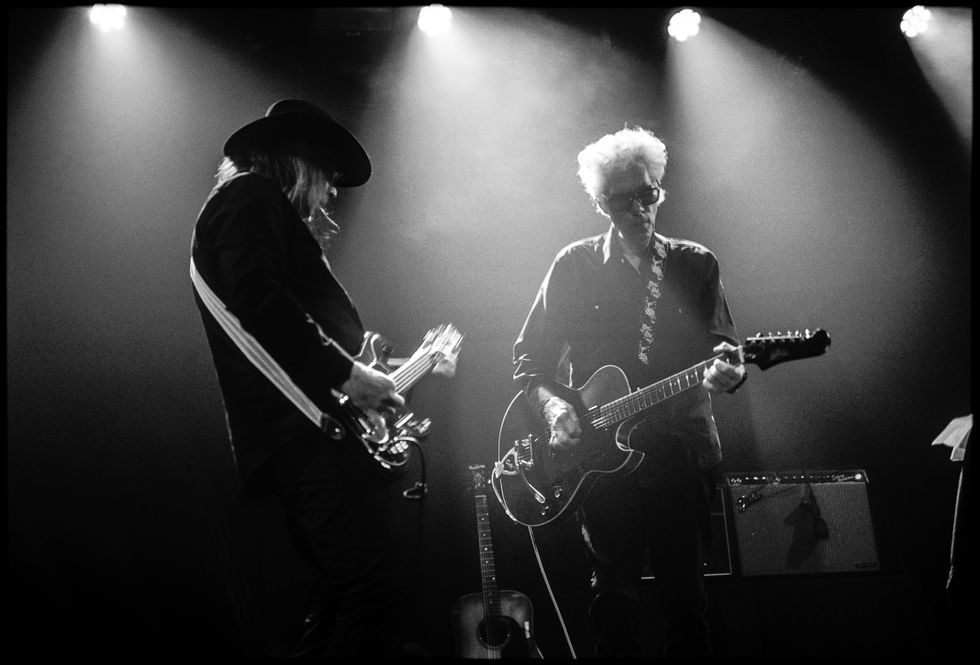

In Stereo also honors Trapp and Bukovac’s friendship, which ignited when Trapp and Bukovac met over a decade ago at Nashville’s 12 South Taproom eatery and club—an after-hours musician’s hangout at the time. They also sometimes played casually at Bukovac’s now-gone used instrument shop, but when they’re onstage today—say at Trapp’s Monday night residency at Nashville’s Underdog, or at a special event like Billy Gibbons’ BMI Troubadour Award ceremony last year—their chemistry is obvious and combustible.

“Guthrie is very unpredictable, but for some reason our two styles seem to mix well.”—Tom Bukovac

“It’s like dancing with somebody,” Bukovac says about their creative partnership. “It is very easy and complementary. Guthrie is very unpredictable, but for some reason our two styles seem to mix well, although we play very differently.”

As Pepé Le Pew probably said, “Vive la différence.” While they’re both important figures in Nashville’s guitar culture as badass, in-demand session and live players, Trapp also points out that the foundation of their respective careers is on opposite swings of that pendulum. Bukovac’s reputation was built on his studio work. Besides his touring history, he’s played on over 1,200 albums including recordings by the Black Keys, Glen Campbell, Keith Urban, Stevie Nicks, Bob Seger, and Hermanos Gutiérrez. And Trapp considers himself mostly a stage guitarist. He emerged as a member of the Don Kelly Band, which has been a Lower Broadway proving ground for a host of Nashville 6-string hotshots, including Brent Mason, Johnny Hiland, and Redd Volkaert. In recent years, you may have seen him on the road with John Oates. It’s also possible you’ve heard Trapp on recordings by Rodney Crowell, Emmylou Harris, and Roseanne Cash, among others.But back to In Stereo. “This record is truly for the love of music and not giving a shit what anybody else is going to think about it,” relates Trapp, as he, Bukovac, and I sit and talk, and they noodle unplugged on a Danocaster and an ES-355, respectively, in the warm, instrument-filled surroundings of the Cabin Studio in East Nashville. The album was recorded there and at another studio, simply called the Studio, with Brandon Bell engineering.

“When we started working on the album, it was very loose,” explains Bukovac. “I never wanted to bring in anything that was complete because the key is collaboration. So, I knew better than to come in with a complete song. And Guthrie didn’t do that either. We would just come in with a riff for an idea and then let the other guy finish it—and that’s the best way to do it.”

“It’s got enough humanity—real playing—mixed with the cinematic side of it.”—Tom BukovacAll of which helped make In Stereo’s 11 compositions seamless and diverse. The album opens with a minute-long ambient piece called “Where’s the Bluegrass Band,” which blends acoustic and electric guitars, feedback, and keyboards with generous delay and reverb—telegraphing that listeners should expect the unexpected. Of course, if you’ve been following their careers, including their estimable YouTube presence, you’re already expecting that, too. So, a soulful composition like “The Black Cloud,” which builds from a Beatles-esque melody to a muscular and emotive power ballad of sorts, comes as no surprise. “Desert Man” is more of a mindblower, with its dark-shaded tones and haunting melodies. “Cascade Park” is an unpredictable journey that begins with delay-drenched piano and leads to Trapp’s acoustic guitar, which evolves from contemplative melody to feral soloing. And “Bad Cat Serenade” and “Transition Logo Blues” balance the worlds of country and jazz fusion. Overall, the music is timeless, emotional, and exploratory, creating its own world, much as Ennio Morricone did with his classic film soundtracks.

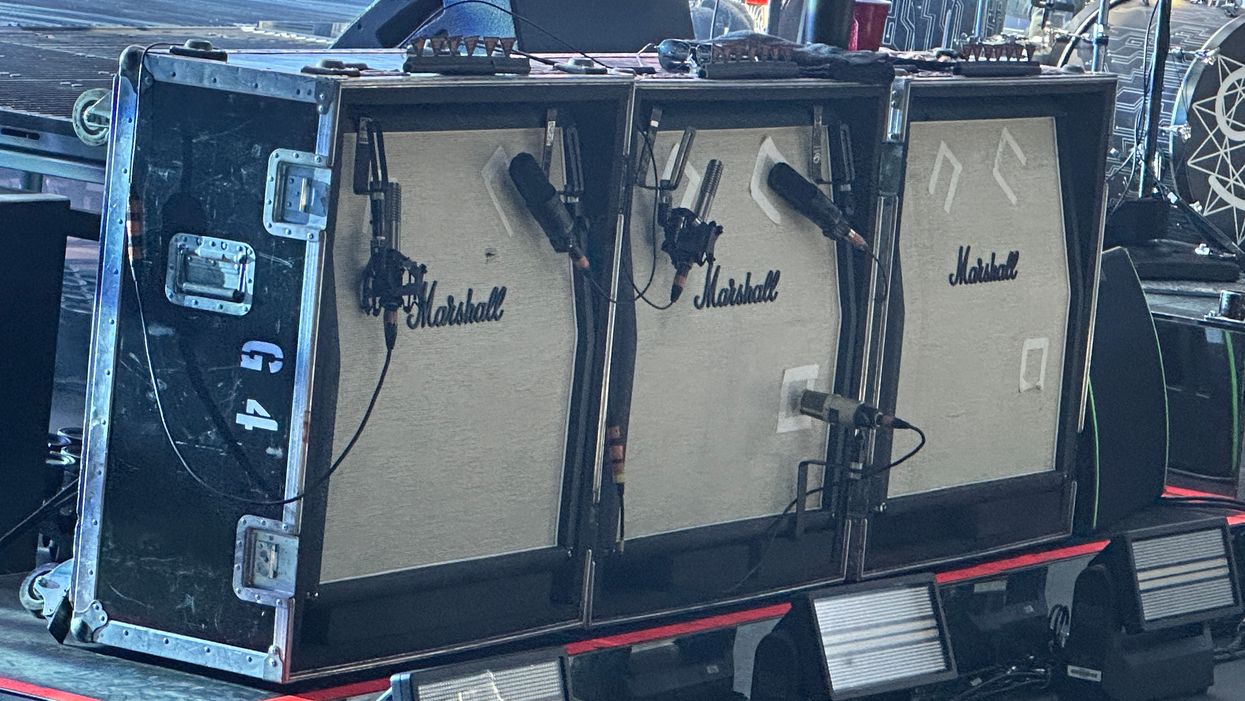

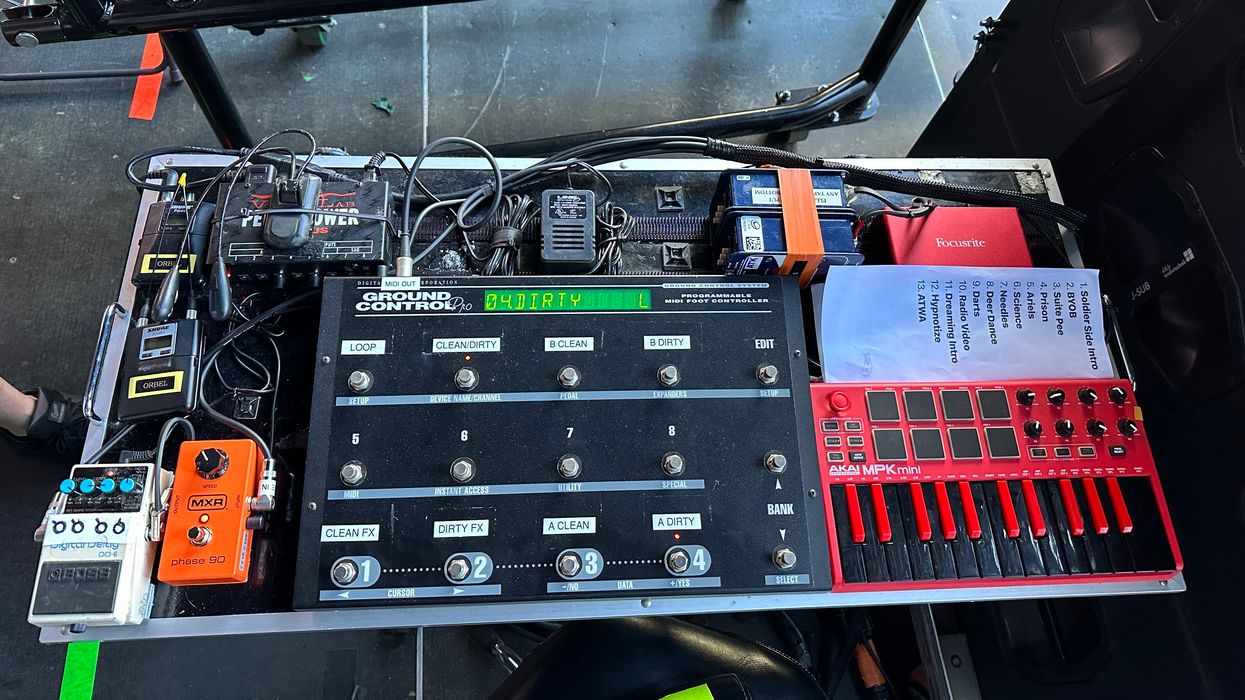

Tom Bukovac's Gear for In Stereo

Tom Bukovac and his ’58 Les Paul sunburst—one of just a handful of guitars he used to record In Stereo.

Guitars

- 1958 Gibson Les Paul ’Burst

- 1962 Stratocaster

- Harmony acoustic rebuilt by James Burkette

- Jeff Senn Strat

Synth

- Roland XP-30

Amp

- Black-panel Fender Princeton

Effects

- Nobels ODR-1

- Strymon Brigadier dBucket Delay

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario NYXL’s (.010–.046)

- Fender Mediums

“It’s a lot to ask somebody to sit and listen to an instrumental record,” Bukovac offers, “so I was just trying to make sure—and I know Guthrie did the same—it doesn’t get boring. When I finally sat and listened to this thing in its entirety, which was many months after we actually recorded, I had forgotten what we’d even done. I was overwhelmed. I love that I never got bored. It moves along and has moments where it gets into sort of a trance, in a good way, but it never stays there too long. It’s got enough humanity—real playing—mixed with the cinematic side of it.”

Trapp picks up the thread: “If you’re in Nashville for a long time and you’re paying attention at all, you understand this is a song town. No matter how you slice it, it’s all about the vocal and the lyric and the song. So, it doesn’t matter if you’re making an avant-garde instrumental guitar record. That influence is pounded in your brain—how important it is to trim the fat and get down to the song. A song is a song. It doesn't matter if it’s instrumental or not. It’s a ‘Don’t get bogged down and get to the chorus’ kind of thing.”

“A song is a song. It doesn’t matter if it’s instrumental or not. It’s a ‘Don’t get bogged down and get to the chorus’ kind of thing.”—Guthrie Trapp

Which alludes to the sense of movement in all these compositions. “It’s very important that every section of a song delivers every transition,” Bukovac adds. “When you go into a new room, when you open that door, it’s got to be right. That’s what I think about records. And there’s a lot of shifting on this record. We go from one field to another, and were very concerned about making sure that each transition delivers.”

Guthrie Trapp's Gear for In Stereo

Guthrie Trapp recording with his Danocaster Single Cut, made by Nashville’s Dan Strain.

Guitar

- Dan Strain Danocaster Single Cut

Amps

- Kendrick The Rig 1x12 combo

- Black-panel Fender Princeton

Effects

- Strymon Brigadier dBucket Delay

- Strymon Lex

- Nobels ODR-1

- Xotic RC Booster

- T-Rex Tremster

- Boss TU Tuner

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario NYXL’s (.010–.046)

- Medium celluloid

That kind of thoughtful development—the set up and delivery of various compositional sections in songs—isn’t exactly a lost art, but it’s certainly rarer than in earlier decades. Listen to Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road to hear how Davey Johnstone sets up verses, choruses, and bridges—or anything by David Gilmour—for reference. It’s also a goal best accomplished with a team of exceptional players, and, of course, Trapp and Bukovac enlisted some of Music City’s finest. The cast includes steel-guitar legend Paul Franklin, keyboardist Tim Lauer, bassists Steve Mackey and Jacob Lowery, and drummers Jordan Perlson and Lester Estelle.

“Don’t tell my mom, because of course we all want to make a living, but playing music that has integrity is at the top for me.”—Guthrie Trapp

“We recorded the basics—really, most of the tracks—live on the floor,” says Trapp.

“We kept a lot of the original throw-down/go-down solos,” Bukovac adds. “There were very few fixes and overdubs. One of the best moves we made was letting an outside person objectively sequence it, because you can get a little bit too inside your own thing. It’s like … if you’ve ever done a photo shoot, if you let somebody else choose the photo, it’s never going to be the one you’d choose, and it’s probably a better choice.” That task fell to bassist and singer Nick Govrik.

The terrain Bukovac and Trapp cover on their first album together is expansive and transporting—and packed with impressive melodies and guitar sounds.

The shipment of In Stereo’s vinyl arrived shortly before Trapp, Bukovac, and I talked, and while Bukovac released his first solo album, Plexi Soul, in 2021, and Trapp put out his releases Pick Peace and Life After Dark in 2012 and 2018, respectively, they seemed as excited to listen to it as teenagers in a garage band unveiling their debut single. That’s because, despite their standing and successes, playing guitar and making music is truly in their blood. What they play is a genuine expression of who they are, ripped from their DNA and presented to the world.

“Don’t tell my mom this, because of course we all want to make a living, but playing music that has integrity is at the top for me,” says Trapp. “These days, with AI and people worried or insecure about where the music business is going, and all these Instagram players who just are fixing everything with Pro Tools so they sound like they’re in a studio, I don’t worry because we’re not selling bullshit. We have 35 years of real experience between us, and when we do social media, we’re just reaching for a cell phone and posting it. It’s organic. That, to me, is a big difference. At the end of the day, I can sleep well knowing that I have earned the respect of the people that I respect the most. It’s just authentic music made for the very reason we got into this in the first place. We love it.”

YouTube It

Guthrie Trapp and Tom Bukovac practice their live chemistry together at Trapp’s standing Monday night gig at Nashville’s guitar-centric Underdog.

Though both heavy players in the soul and funk world, Feingold and Hunter first met via Instagram.

Though both heavy players in the soul and funk world, Feingold and Hunter first met via Instagram.