To some, Americana is a fashion or aesthetic. To others, it’s a music genre. Many also relate it to film. The thing that ties them all together is an emphasis on authenticity and heritage. Americana, in any form, takes the country’s roots and brings them to the people in an honest, reverent way. In that sense, Blackberry Smoke’s latest vintage-gear-fueled release, Be Right Here, is Americana at its finest.

Like the band, the album is a mix of just about every uniquely American musical genre wrapped into one. From the mountain-country calm of “Azalea” to “Watchu Know Good”’s smokey barroom groove, Blackberry Smoke is what happens when real musicians tell authentic stories through great songs.

Listening to lead vocalist/guitarist Charlie Starr and guitarist Paul Jackson name-check their influences, it’s apparent where they got their versatile yet classic sound. For Jackson, it was simple.

“My dad asked me, ‘Do you want to hear something really cool?’” he remembers. “He put on Chuck Berry, and that was that for me. I got turned on.”

“I grew up playing bluegrass and gospel and traditional country music with my dad,” Starr adds. “But my mom liked the Stones, the Beatles, and Bob Dylan. He says these influences and Jackson’s high-pitched vocal ability brought the two together over two decades ago.

“I remember hearing [Ratt’s] Out of the Cellar for the first time, which is something that me and Paul really bond on, and we were playing the same honky-tonks and little bars around West Georgia and East Alabama,” Starr continues. When he moved to Atlanta, he met brothers Brit and Richard Turner, who would become Blackberry Smoke’s drummer and bassist.“I had started writing some songs coming from bluegrass and southern rock music and was like, ‘Well, we need another guitar player, and we need somebody who can sing high.’ Harmony is very important, but the only bands that could sing around there were my band and Paul’s bands,” Starr chuckles. “I called Paul and was like, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing, but we’re putting this band together. Would you like to be in it?’”

“That was that, and here we are,” Jackson laughs, “23 years later.”

Since then, Blackberry Smoke—which also includes Brandon Still (keyboards), Preston Holcomb (percussion), and Benji Shanks (guitar)—has taken their music around the world, garnering fans and critical acclaim. Starr’s bluegrass-meets-southern rock sound has also grown to embrace the best elements of blues, country, soul, jazz, and R&B. These genres share a traditional heritage, one that comes from the Southern states Blackberry Smoke calls home.

“My dad asked me, ‘Do you want to hear something really cool?’ He put on Chuck Berry, and that was that for me.” —Paul Jackson

Blackberry Smoke’s music is definitely a kind of stylistic and cultural gumbo. But, according to Starr and Jackson, the recipe only comes together because of the players that make up the band. “It’s the way that people play their instruments and the way that they express themselves, all seven of us,” says Starr. “You get the way that the instruments are being played and then the way that it’s all glued together. That’s where two decades of playing together comes into it. It’s like a football team where everybody’s moving and working toward the same goal.”

Be Right Here, Blackberry Smoke’s eighth album, was recorded live off the floor by Dave Cobb, who wanted to capture the band as they learned the songs.

Be Right Here embodies that human element better than, perhaps, any of the band’s previous work. Together with producer Dave Cobb, they took their already honest approach to writing and recording and stripped it back even further, tracking right off the live room floor. While there may have been some initial hesitations, Starr said the process soon proved its value.

“I had my doubts at first, but he had already done it. I think just previously, he had made Slash and Myles Kennedy’s newest record that way. He just said, ‘I want everything in the room and everybody in the room.’ There’s some bleed, but it was really about the feel, and he was right.”

“That’s where two decades of playing together comes into it. It’s like a football team where everybody’s moving and working toward the same goal.” —Charlie Starr

That “feel” dominates the record. From the greasy riffs of lead track “Dig a Hole,” the guitars are loose, raw, and packed with attitude, just like the classic records of rock’s heyday. That’s no accident.

“Dave’s coming from that ’60s recording mentality,” explained Starr. “He doesn’t allow a click or auto-tune. It’s all analog. That’s his MO. And if you think about it, we all spend every waking hour in the studio chasing records that were made in the ’60s and ’70s, because it sounds so good. Especially as guitar players and instrumentalists, it’s like, man, that’s the pure drop right there! It’s the way that Neve consoles and Neumann microphones make music sound.”

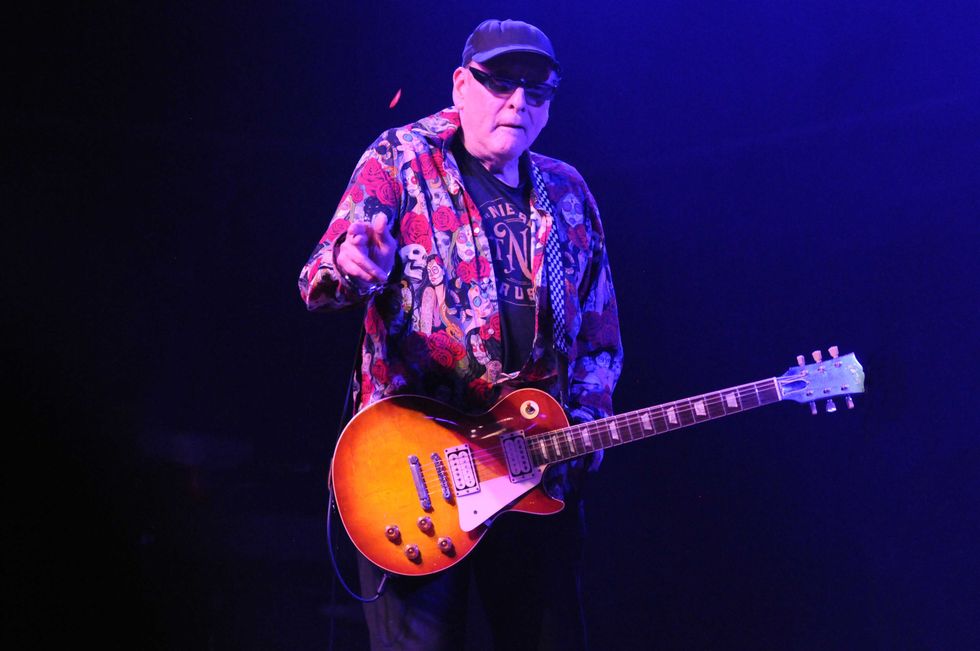

Charlie Starr's Gear

Starr and Jackson usually drop off a truckload of high-wattage amps at the studio when they record, but Cobb encouraged them to keep things small and simple.

Photo by Steve Kalinsky

Guitars

- 1964 Gibson ES-335

- 1957 Gibson Les Paul Junior

- 1963 Fender Esquire

- 1958 Fender Telecaster

- 1965 Gibson ES-330

Shared Acoustics:

- 1950 Martin D-28

- 1953 Martin D-18

- 1946 Martin 000-18

- 1955 Gibson J-45

Amps

- 1964 Fender Champ

- 1950s–’60s Supro Super

- 1950s Fender Custom Champ (modified to Dumble spec)

Effects

- 1990s Menatone Red Snapper

- Vintage MXR Phase 45

- Vintage Maestro EP-3 Echoplex

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario (.010–.046)

- Blue Chip picks (acoustic)

- InTune picks (electric)

Tracking live through classic studio gear wasn’t the only way Cobb and the band changed things for the new record. Much to Starr’s surprise, Cobb also wanted the band to come in fresh—as in, not-having-heard-the-songs-before fresh. Starr remembered Cobb saying, “Hey, man, don’t send demos of the songs to the guys this time. Don’t even play the songs yet. I want you to sit in the studio, get the guitar, and say, ‘The song goes like this.’ I want to capture the first thing that people play when we start to roll tape. That’s usually the best.

”As a result, often what you hear on Be Right Here is the sound of seven talented musicians playing off each other and reacting to the music in real-time like only a band of musical brothers can. Not even the band’s gear escaped Cobb’s less-is-more approach. Jackson and Starr, both diehard vintage-gear collectors, are well known for using Marshall and Marshall-style heads and cabinets. But Starr said the amps hardly got any use in the studio.

“If you think about it, we all spend every waking hour in the studio chasing records that were made in the ’60s and ’70s, because it sounds so good.” —Charlie Starr

“Over the last 20 years, you know, we’ll go to make a record, and then it’s like, ‘Oh, I can’t wait to take this Plexi to the studio,’ or, ‘I got this new Bandmaster I can’t wait to take in,’” he explains. “We’ll literally bring a truck full of shit. And Dave’s got a whole studio full of shit. But Dave called and said, ‘Hey, call Benji and Paul and tell them not to bring any amp bigger than a 10" speaker. Let’s make a funky little amp record.’”

“And, believe it or not, I used just two amps on this record,” adds Jackson. “They just sounded great. I was on the verge of just using one, my Gibson Lancer. It’s a ’59. I used it for most of the record. Then, I think, on the last two songs, it took a dump on me, and I used Dave’s ’58 or ’59 Rickenbacker amp for the last songs.”

Starr kept his recording rig just as streamlined. On almost every song, you can hear him play through a 1964 black-panel Fender Champ, with a few cameos from a Supro Super. But the holy grail turned out to be a 1950s Fender Custom Champ, which had some particularly special magic.

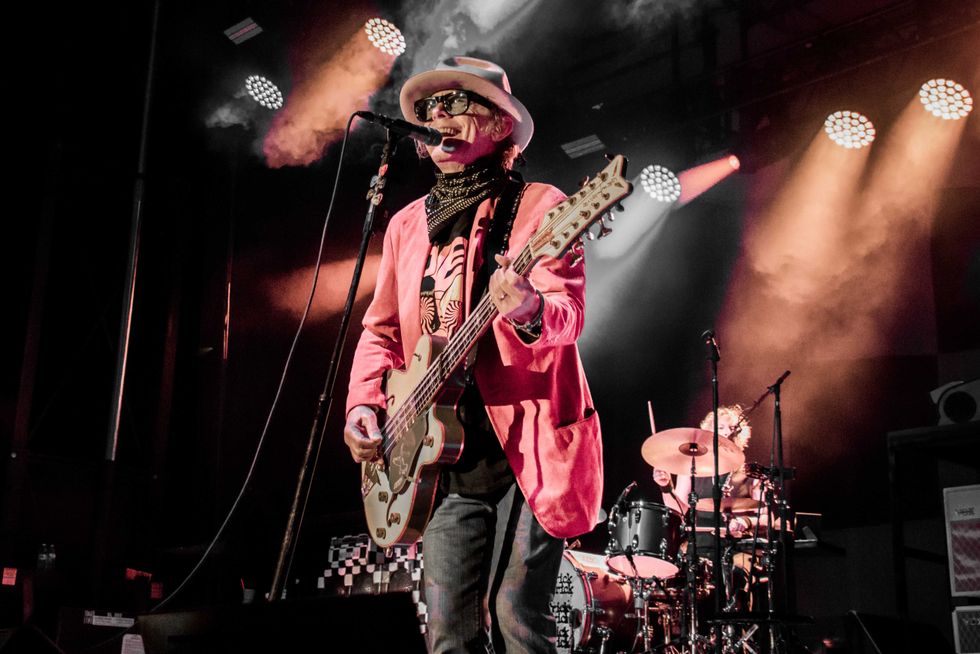

Paul Jackson's Gear

Guitarist Paul Jackson says the best solos ought to sound like you’re singing.

Photo by Jordi Vidal

Guitars

- 1960 Gibson ES-335 (owned by Dave Cobb)

- Gibson 40th Anniversary Les Paul

- 1979 Gibson Les Paul Standard

Amps

- 1958–’59 Rickenbacker combo

- 1959 Gibson GA-6 Lancer

Effects

- Neo Instruments Ventilator

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario (.010–.046)

- InTune picks

“Dave actually had an email from Dumble that he showed me. He’s like, ‘This is the advice that I got from Dumble on what to do with your Champs and Princetons.’ I can’t tell anyone what it said. It’s a Dave Cobb, Howard Dumble secret. But it was a speaker trick. Our tech was out there with his soldering iron, like a crazy professor, modding these vintage amps on the live room floor.” The unmistakable tweed grit on “Don’t Mind If I Do” is just one of the stellar guitar tones that drive Be Right Here.

Both Jackson and Starr managed to work a few of their favorite pedals into the sessions as well. “I actually fell in love with this pedal that Dave had called a Red Snapper by Menatone,” Starr says. “It was a mid-’90s pedal. I was like, ‘Dude, that is great! I got to have one of those.’ It’s Klon-ish but a little brighter, actually. And you were using a [Neo Instruments] Ventilator for the solo for ‘A Little Bit Crazy.’ Isn’t that what it is?” Jackson confirms. “The chase never ends, does it?” Starr continues. “You can’t help it.”

“The way I look at it is, we’re singers anyway. When we play guitar, the vocal comes through the guitar.” —Paul Jackson

There are delicious tones to be found on every song, and getting those tones was a journey in itself. Because of their tracking process, each sound had to fit the whole and perfectly translate the songs’ meanings. Cobb and the band understood this, and as Starr explains, they took their time dialing things in one chord stab at a time. “For each song, [Dave would] plug in a little amp, and you’d hit a G chord. He’s like, ‘No.’ Then it’s like, ‘Okay, how about this little Super amp?’ He’d be like, ‘No.’ Then you land on the one, and he goes, ‘That’s it!’ He would do that with every person in the band.”

“That chase is the fun part to me,” adds Jackson. “When you’re in a room with a bunch of guys and trying to find that sound, it’s exciting. I could sit there all day and just listen and watch.”

Photo by Andy Sapp

Southern rock revivalists Blackberry Smoke have been going strong for 23 years, and guitarists Charlie Starr and Paul Jackson say they have no intentions of slowing down.

While both Starr and Jackson put many of their vintage instruments to work during those sessions, Jackson spent a lot of time working one of Cobb’s prized 6-strings. “I mainly used Dave’s blonde ES-335,” he says. “He said it was a late ’50s or early ’60s. I fell in love with that. I used it for most of the tracking.” Jackson also turned to his black 40th Anniversary Les Paul and a ’79 Standard Les Paul, but the 335 won the day.

Starr relied on his personal arsenal of old-school Gibsons and Fenders, including a 1964 ES-335, a ’65 ES-330, a ’57 Les Paul Junior, a ’63 Esquire, and a ’58 Telecaster. Of course, great songwriters are never far from their favorite acoustic guitars, and Blackberry Smoke gets the most out of a prized collection that includes a 1950 Martin D-28, a ’53 D-18, a ’46 000-18, and a 1955 Gibson J-45.

“I called Paul and was like, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing, but we’re putting this band together. Would you like to be in it?’” —Charlie Starr

The band’s gear and tones are likely enough to make most Premier Guitar readers misty-eyed. To Starr and Jackson, though, they are a means to an end. To them, it’s still all about the songs and the emotions. This goes double for their approach to solos, of which there are plenty on the new LP.

“When I’m putting together a solo for a song, the best place to start is the melody of the vocal,” explains Starr. “Then just expand on that. I mean, when you’ve played with traditional bluegrass guys, if you came in there playing a solo on ‘Faded Love,’ and you aren’t playing the melody, they’d be like, ‘What the hell are you playing? You’re not playing the song!’”

“The way I look at it,” Jackson adds, “is we’re singers anyway. When we play guitar, the vocal comes through the guitar. That’s what gets me on solos. I could rip at home and do that by myself. I’m not worried about that. It’s about the songwriting, and when I hear Charlie throw something out there, it just works.”

The duo agrees that rhythm is 90 percent of a guitarist’s gig, which is why they complement each other’s rhythm styles perfectly. Even on straight-up rockers like “Hammer and the Nail,” the two fill the space with a combination of powerful chords, punctuating slide flourishes, and Stones-like juxtaposition. Starr admits that it’s something they’ve worked on since day one.

“Paul and I, in the early days of the band, had talked about not doing the same exact thing and how it’s so interesting for a two-guitar band. Think about it: When we were young, and we listened to Highway to Hell, you would turn the balance left and right [on the stereo] and get Malcolm on the left and Angus on the right. It was always a little different. Even Appetite for Destruction. That’s an even better example of how Izzy and Slash played totally different parts. That’s what Keith Richards and Ron Wood talk about, taking these different parts and making something greater.”

Blackberry Smoke’s 23-year career shows how far you can go with a handful of chords and the honest truth. Through rock’s attitude, blues’ swagger, bluegrass’ melodicism, and soul’s sensuality, they keep creating records that resonate with fans worldwide.

Yet in the modern music age of algorithms and AI, you have to ask: What keeps them going? Why crank old guitars into tube amps after all these years? The romantic answer is, “the song.” The more practical answer—and every bit as true—is that they simply have to.

“It’s an addiction,” says Starr. “Look at the Stones. They’re 80. They can’t stop.”

“Exactly,” agrees Jackson. “It’s still exciting.”

YouTube It

Blackberry Smoke takes a soulful ramble through their hit, “One Horse Town,” live in Atlanta back in 2019.