Before Joe Silvius started working for Martin 27 years ago, he thought he was going to become a professional baseball player. When his shoulder told him he could no longer pitch, however, he was forced to come up with a plan B. He grew up five minutes away from the Nazareth, Pennsylvania, factory, and, given that his father, brother, aunts, and uncles had all worked there, taking that path for himself only made sense. Unexpectedly, it turned out to be an ideal one.

“I can’t explain it. It’s incredible. It really is,” he says. “Obviously there’s thoughts—I’m sure everybody has them—of something else, maybe better, but I can’t see anything better than this.”

Here at Premier Guitar, we’ve done profiles on master guitar builders in the past. But unlike many guitar factories around the country, Martin doesn’t have master builders, exactly. They rely on a crew of highly skilled specialists, rather than individuals who oversee a guitar’s production from start to finish. Silvius, whose title is exotic tonewood specialist, is one of the former.

After the loss of his baseball career prospects, Silvius left college to work at the factory, where he started out in the string division. He then moved on to fretting, and then pre-finish (which involves body sanding before finish is applied), where he stayed for two years, eventually running the department. About 23 years ago, he switched over to the sawmill and acclimating areas, and for the past six or seven years, he’s been working in the custom shop as well. There, he’s responsible for guiding dealers in selecting the perfect wood for their custom builds.

“Obviously there’s thoughts—I’m sure everybody has them—of something else, maybe better, but I can’t see anything better than this.”

But before that can happen, incoming wood—that ends up on the shelves for dealer selection—must be inspected and acclimated, or dried. Now, when it comes to guitar building, wood drying may not sound like the most thrilling aspect. But after forests and lumber yards, it’s where guitars begin, and if that core material isn’t handled with care, intuition, and technical expertise, there would be no guitars from Nazareth (or anywhere else, for that matter).

Part of Silvius’ expertise is knowing how to treat a wide variety of tonewoods to reduce their moisture content—the woods Martin accepts can come in at up to about 40 percent—to the desired range of six to eight percent. The process involves “sticking,” where cut pieces of lumber are literally placed on horizontal support “sticks” of wood to enable air to flow through them. Then, the wood is placed in a kiln set to temperatures specific to the species being dried (as high as around 160°F), until the ideal moisture content is reached.

Silvius explains that customers have been increasingly interested in seeing unusual grain patterns on their guitars, such as that shown by this cocobolo back.

Courtesy of Martin Guitar

Sometimes, wood is brought below that desired range and then reacclimated, which helps to “stabilize the wood for less issues in the future,” explains Silvius. But every species dries differently, and has to be handled carefully to ensure that it survives the process: If it’s dried too much, the cells in the wood will die, making it brittle, which also prevents reacclimating. If it’s dried either too quickly or too slowly, it can lead to different types of damage that make the wood unusable.

Ebony, for example, takes six months to dry—if it’s done any faster, it will crack. “I would say ebony is probably the most complicated,” Silvius explains. “We’ve gotten really good at controlling it. Everybody wants ebony for their fretboard and bridge, so we gotta make sure we keep that in as good of shape as possible.” Then there are other woods like gonçalo alves, “which is a rare wood—it’s hard to work with. It doesn’t like to stay flat. We put plastic bands around it to help keep pressure on it to try to keep it as flat as possible.” Other tonewoods, like rosewood and sapele, are more forgiving, and take just two weeks to dry before they’re put in the kiln.

If you’re wondering about torrefaction (the process of drying wood at an extreme temperature to capture the sound quality of vintage guitars), that’s done by a vendor offsite. Silvius explains that it requires a specialized kiln with a controlled low-oxygen atmosphere, and a proprietary “recipe.”

Having worked in the acclimating area for more than two decades, Silvius is knowledgeable on how to put a wide variety of tonewoods through the drying process.

Once the incoming wood has gone through the acclimating process, it’s then ready for the production line, and the custom shop. For the uninitiated, the custom shop offers a unique experience for dealers from around the world to come in and design their own guitars to be sold at their locations, down to choosing the type and sets of wood to be used. The designs themselves may not be “exclusive,” per se—as dealers’ requested builds might be similar to those chosen by peers—but are often created with their specific customer base in mind. (The custom shop also has guitars pre-built for dealer selection, if they might be interested in buying a finished model as opposed to designing it themselves.) Some recent visits have been from Haggerty’s Music from South Dakota, Reno’s Music from Indiana, Empire Music from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Andertons Music Co. from the U.K.

“The piece of wood that they select has to speak to them. It’s all a perception. Everybody loves things differently.”

“Every dealer is different,” Silvius comments. “Some come in with an actual plan. They know what guitars they want; they know what species they want. They get a list, come in, do their thing, and leave. For others, it’s like a supermarket. They look at the shelf and say, ‘Let’s take a look at some of this.’” A lot of Martin’s exotic woods are kept in locked cages that only a handful of employees have access to, Silvius being one of them.

“I’m not much of a salesman,” he adds. “When they come in, I shoot ’em straight. I’m not going to tell you something just because I want you to buy this guitar. That’s not what I’m about. The piece of wood that they select has to speak to them. It’s all a perception. Everybody loves things differently.”

In the past, Martin would have rejected wild-grain East Indian rosewood for its nontraditional patterns, seen here.

Courtesy of Martin Guitar

Sometimes, the selection process can lead to some humorous, unconventional scenarios. One year, a group of dealers came in from Japan, who were all interested in the same pre-built model. “The custom shop director brought in a putting mat, and they actually putted,” Silvius says, laughing. “Whoever made the putt got the opportunity to buy the guitar. It’s just fun.”

Silvius says that the cultural trend in the guitar world over the past several years has been all about aesthetics: wild-grain East Indian rosewood, striped Gabon ebony, flame and quilted maple. Customers today are looking for something more distinctive in a guitar’s appearance—and that trend has steered Martin in a wildly different direction from where they’d been for decades. “It was about tradition, so everything had to be perfectly quartersawn [cut to yield straight-grain pieces]. If it wasn’t, we would reject it. But now, people love the look of the [different grain patterns]. Doesn’t necessarily affect the guitar—the sound or anything. It just gives you that ‘wow.’”

“We took a trip to New York recently,” Silvius shares. “I was at Rudy’s [Music], who’s going to be here next week to select wood, and the gentleman who works there was telling me what he wants. He likes more traditional, straight grain. But he needs something that his customers are going to turn around and go, ‘Wow, the back just looks incredible.’ These dealers know their customer base. They have regular customers that come in, and they know what they want.”

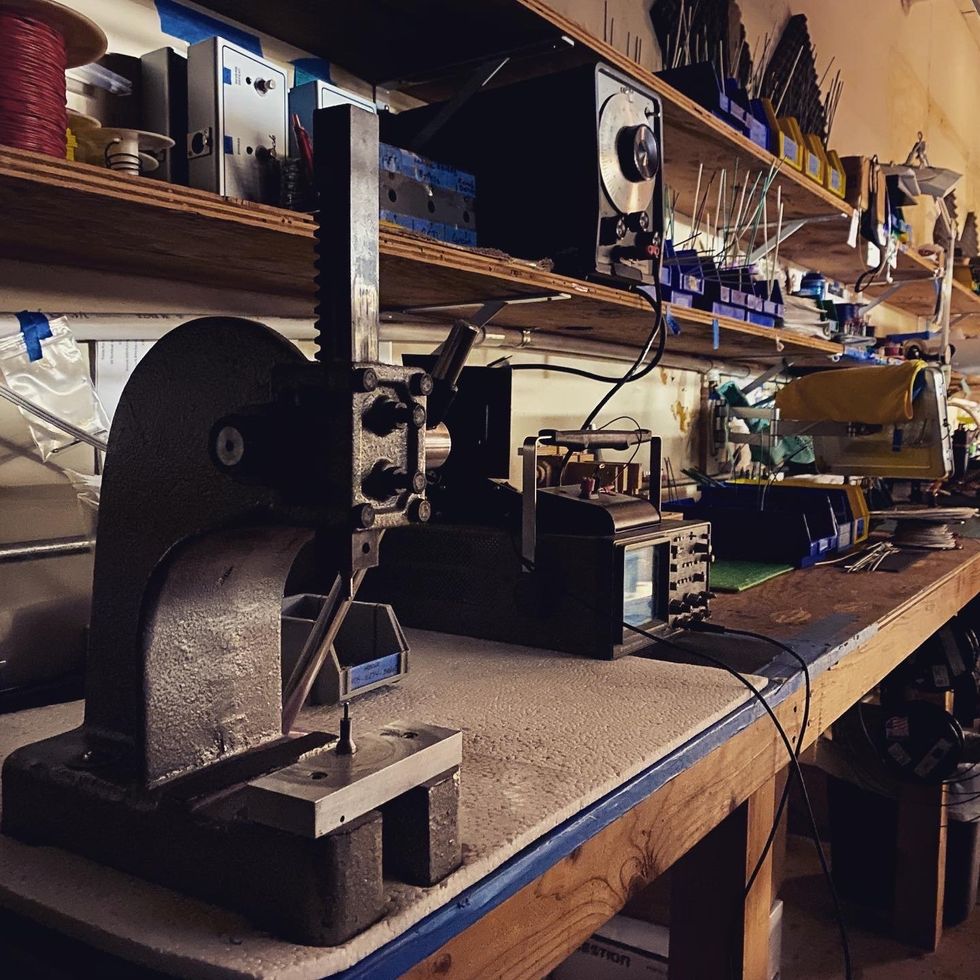

In Martin’s custom shop, Silvius guides dealers in selecting the right woods for their custom guitar designs.

As Silvius alluded, quartersawn wood has straight grain, and has long been highly sought-after. But it’s becoming scarcer, partially because in order to get it, harvested trees have to be at least 24″ in diameter. A less expensive alternative, flatsawn—one of the kinds Martin used to reject—produces wood with “cathedral,” or spire-shaped, grain patterns. And especially given the shift in popular preference, Martin has been bringing more flatsawn wood into their production line. However, Silvius comments that flatsawn is harder to work with, as the pieces can be fickle: “It twists. [Some pieces often] turn into almost like a potato chip and we can’t use it. But other pieces stay flat.”

Aside from handling unruly wood, Silvius’ biggest challenge in his work overall, he says, is “probably our own internal specs. We are so critical of the material itself. Our standards are set so high that sometimes we are our own worst enemy. Because we want everything to be perfect, and it just can’t be. It’s wood. Even when I match sets—we like everything to have perfectly matching grain or perfectly matching color, or both, and sometimes you just can’t. We beat ourselves up over it.”

“People love the look of the [different grain patterns]. Doesn’t necessarily affect the guitar—the sound or anything. It just gives you that ‘wow.’”

When Silvius plays more of a role in selecting the wood for a dealer, which can be another option in the custom shop experience, it becomes a bit more personal for him. “I try not to take much home with me, but I do,” he laughs. “Say they want a high-end D-45, and I gotta select either the Brazilian rosewood, or maybe the cocobolo. Did I make the right choice? Are they really going to be happy with that guitar when they get it? But I’ve also had dealers come in that, when I would meet them for the first time, say, ‘So you’ve been picking out my wood! Thank you,’ and just give me a handshake. It feels great when that happens.”

Ultimately, Silvius says it’s those relationships that make up the best part of his job. It doesn’t hurt that, because Martin employs so many Nazareth locals, he also works alongside many people whose family members he grew up with. “It is a really close-knit community. Even the VP [Deb Karlowitch], she retired a couple years ago, but I graduated with her son. Her husband, when we walked home from school, would pick us up sometimes on the way.”

As Silvius emphasizes the passion that Martin’s roughly 500 employees have for their work, which he says speaks to their consistently high-quality products, it might surprise you that he doesn’t play guitar. “It’s funny, because I’m not a guitar guy. I’ll be honest with you,” he admits. “I always blame it on having short, chubby fingers.

“I wish I would have tried to learn during [the pandemic]. I still want to learn to play, I just gotta get into the right mind-frame. My kids are now older, so I’m not going to sporting events and everything. It’s time I should learn.”