Woody Mann loved John Monteleone’s guitars so much, he thought there should be a movie about them.

After years of playing Monteleone’s legendary archtop guitars, Mann, the great fingerstyle player who died in January 2022, pitched his filmmaker friend Trevor Laurence on a documentary following Monteleone’s work. Laurence agreed, and when Mann shared the idea with Monteleone, the luthier had just one condition.

“I said, ‘Sure, sounds good, as long as we can do it in a way that allows me to express the artistic side of creating these instruments over the years,” says Monteleone over the phone from his home in Long Island, New York. “Not only the fine art of instrument making, but the fine art of art itself.”

This, in a nutshell, is the story of John Monteleone: The Chisels Are Calling, the new feature-length documentary directed by Laurence and produced by Laurence and Mann. The film burrows through Monteleone’s life story, from childhood tinkerer to world-revered archtop luthier, but it also serves as a profound rumination on what moves people to build and create.

John Monteleone: The Chisels Are Calling

Even the documentary’s title reflects this depth. It’s a phrase that Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler, a Monteleone fan, saw the luthier use often while signing off his emails: “The chisels are calling, it’s time to make sawdust.” One day, Knopfler was stringing together new chords and melody. Words began to fit together, and he realized he was writing a song about John Monteleone.

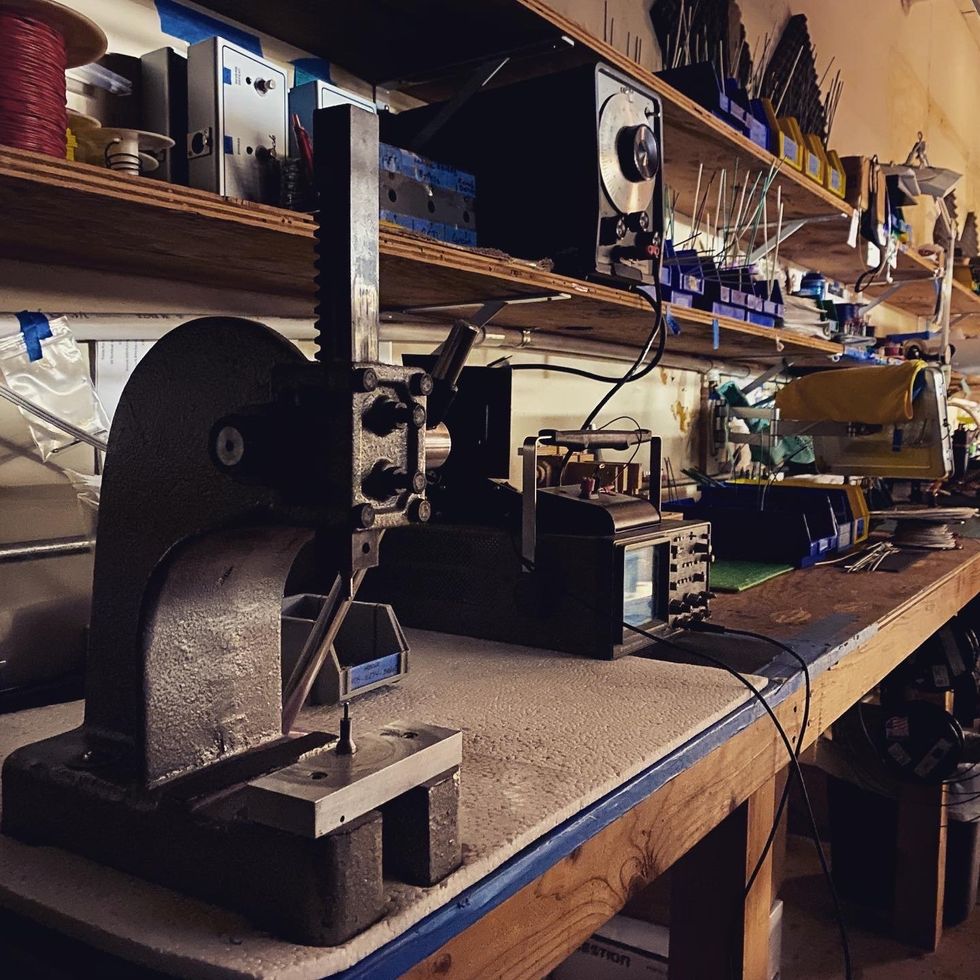

It’s an eyebrow-raising trivia tidbit, but it also suggests something about Monteleone and his work. It’s not just that Knopfler liked his guitars. Monteleone’s process and total commitment to his craft stirred something in Knopfler. At a performance in 2009, he discussed the song and his appreciation for Monteleone. He describes witnessing the luthier in his shop, tapping on different pieces of wood and navigating an array of chisels. Knopfler gathered that something stirred Monteleone to do this work. It was more than a job.

“I realized he has this compulsion to be with his chisels and his work,” Knopfler told the audience. “It was inspiring, so I wrote this song.”

The Chisels Are Calling is a window into Monteleone’s workshop, but it’s also a window into the soul of a creator.

The Operating Table

The Chisels Are Calling documents John Monteleone’s life story, from childhood tinkerer to world-revered archtop luthier, but it also serves as a profound rumination on what moves people to build and create.

Photo by Rod Franklin

Early in the documentary, Monteleone says one of the greatest things that ever happened to him was his family getting a piano. Three years after they bought it, he says, the piano started breaking down, and he convinced his parents to buy a new one. Before it was to be delivered, Monteleone, age 10, asked his mother to “have his way” with the old one: He wanted to tear it apart and study it. She consented, and the young Monteleone set to it, disassembling and diagnosing the marvelous old instrument. Then he started fixing it. By the time the new piano arrived, he had the broken-down beauty fully operational again. Later, he’d use the smash-’em-up tactic again to gain access to the innards of an acoustic guitar sitting around their house.

These were Monteleone’s initiations into a lifetime of repairing, building, and creating. His father was a sculptor, so, from a young age, Monteleone had an appreciation for tools, the people that use them, and the things they make. By 14, he had built his first guitar, a Martin-esque dreadnought. And he just kept building. “Once you start, you just can’t stop,” he says in the film.

In college, he operated on a Harmony 12-string acoustic, repurposing his spruce study desk drawer for tone bars and bracing inside. The guitar lasted a month before it began to “fold up like a banana,” he laughs. But that wasn’t the end: Monteleone took it back to the operating table, cut it open, and fixed it up. After graduating, he got his first professional gig doing repair and restoration for a vintage mandolin shop in Staten Island.

A stunning closeup of John Monteleone’s Grand Central archtop.

Photo to Rod Franklin

The rest of the story is fairly well known. Over the years, inspired by legendary archtop luthiers John D’Angelico and mentor and friend Jimmy D’Aquisto, Monteleone has become, according to former Martin Guitars designer Dick Boak, the “patriarch of the archtop guitar community.” His guitars have been celebrated as works of art and are on permanent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s been a pretty swell ride. Monteleone admits in the film, “I always thought of it like I’ve been retired for the past 45 years.” So, what drew him to the jazzy archtop over other guitars?

“The archtop guitar as an acoustic instrument was not really as well-defined as it could be,” says Monteleone. “When I started building them, there was something else I wanted to hear from them.” As the documentary shows, Monteleone came of age in the American folk renaissance of the 1960s. Fingerstyle guitar playing was exploding in popularity, but it was almost entirely heard on flattop guitars. Monteleone thought it would sound great on an archtop.

“I could hear it, I could imagine it,” he says. So, he set out to build an instrument that would be sensitive enough to satisfy and inspire the flattop acoustic player. He wanted to soften the traditionally metallic treble of archtop guitars and introduce a high-end that was fatter and thicker tonally.

“The harmonic balances became a real issue of focus as well as the extreme other ends, the bass,” says Monteleone. “An archtop guitar tends to do fairly well responsively through the whole mid-section, but to extend the treble and bass regions of the instruments and bring them into a harmonic balance was more challenging.”

In 1995, a collector commissioned John Monteleone to build a guitar with just one condition: It had to be blue. The luthier created the Rocket Convertible, a blue archtop with two ebony-bound soundholes built into the side, with sliding doors so the player can modify how much of the sound is directed to them versus listeners.

Photo by Vincent Ricardel

Monteleone succeeded, as demonstrated through the film by the scores of fingerstyle and hybrid players who have taken up Monteleone archtops for their sensitivity and touch. From Mann to Knopfler to Julian Lage to Anthony Wilson to Ben Harper, Monteleone’s guitars are revered among masters of the craft. But one glimpse of a Monteleone reveals that the instruments aren’t just about function. They’re about form and aesthetics, too. Monteleone has created guitars based on architecture, Art Deco locomotive design, even the four seasons.

In 1995, a collector commissioned Monteleone to contribute a guitar with just one prompt: it had to be blue. The luthier initially set out to build one of his classic Radio City models in blue, but deviated from the path and created the experimental legend Rocket Convertible, a blue archtop that skipped the popular F-hole design in favor of an updated traditional oval soundhole in its spruce top. Monteleone built two ebony-bound soundholes into the flamed maple side facing the player, then fitted both with sliding doors so the player can modify how much of the sound is directed to them versus listeners. They worked like a monitor for the unplugged player, letting them hear more clearly what their audience was hearing. Just like in a classic convertible, a guitarist could roll the top down or put it back up as they pleased.

Archtop Alchemy

Monteleone’s Grand Artist guitars are inspired by his mandolin-making years and feature an elegant scroll on the bass-side bout.

Photo by Rod Franklin

Monteleone’s approach turns a practical instrument into a gesamtkunstwerk: a total work of art. Though it feels novel in a world of mass-production pragmatism, Monteleone is quick to note he’s not the first to elevate form alongside function in musical instruments. It’s a tradition that goes back centuries. “We can go back and look at keyboard instruments, we can look at organs in cathedrals, where the basic instruments had been ornamented to a degree that goes beyond the basic idea, to express or make a connection to what that musical idea is all about,” says Monteleone. Indeed, late in the documentary Monteleone traces the archtop back to its ancestral roots in violin making in northern Italy, where Antonio Stradivari made his masterpieces in the 17th and 18th centuries.

This somewhat luxe approach might strike some as extravagant amid a cultural era structured on planned obsolescence, instant gratification, and minimalism. But for Monteleone, this extra element is the basis of a fuller experience. “The guitar is so accessible, you can pick it up and have at it right away,” he says. “But the musician will sit there and observe, for years, and look at their instrument, and just enjoy the material that it’s made from. That’s a kind of satisfaction that relates to an enjoyment of the instrument beyond what they’re hearing. Now they’re seeing something that is connected to that idea of what they’re hearing.”

He likens it to having a dinner party with friends in a beautiful environment: When the food is great, the company is comfortable, and the setting is pleasing, an evening can be elevated from fine to perfection. Those are the rare evenings that stay in our minds for the rest of our lives.

Monteleone’s archtops serve as a reminder that we are surrounded by and indeed entitled to experiencing beauty and spectacle and wonder—things which often feel impossibly out of reach in the sprint of 21st century life.

“There’s a completion of the experience that really begins to tie it all together when everything is just right,” says Monteleone. “Musically, that’s what we’re doing, trying to express ourselves. We do that with music and also in conversation and many other forms of art. It makes the experience that much more dynamically enjoyable.”

The Thrill of the Hunt

Among their many other functions, Monteleone’s archtops serve as a reminder that we are surrounded by and indeed entitled to experiencing beauty and spectacle and wonder—things which often feel impossibly out of reach in the sprint of 21st century life. So rarely do the stars align to produce a complete harmony of sensory experience, but that’s exactly what Monteleone has been chasing for nearly five decades.

He says his routine hasn’t changed much over time. He’s still dreaming up new sounds and expressions to squeeze out of pieces of tone wood. “I continue to do what you see [in the documentary] every day,” he says. “There’s vision in what I do, and that vision includes what I hear and what I want to hear.”

In his own way, this is Monteleone’s thrill of the hunt: a tense, invigorating pursuit of the sound and feeling in his head. “It’s always maybe a little challenge of expectation,” he says. “I can’t wait to hear if it measures up to what I think I’m gonna hear. When it all turns out right, it’s very rewarding. It’s an exciting thing.”